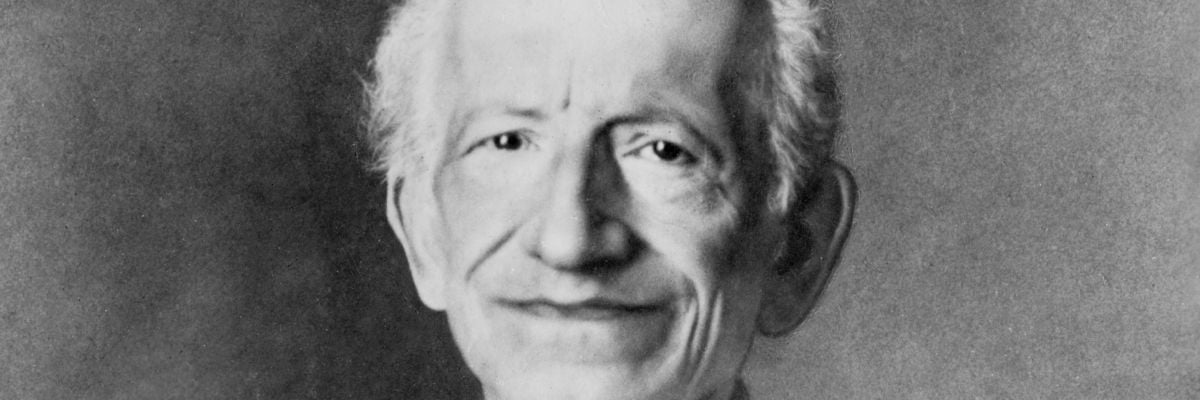

Leo XIII, POPE, b. March 2, 1810, at Carpineto; elected pope February 20, 1878; d. July 20, 1903, at Rome. Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi was the sixth of the seven sons of Count Lodovico Pecci and his wife Anna Prosperi-Buzi. There was some doubt as to the nobility of the Pecci family, and when the young Gioacchino sought admission to the Accademia dei Nobili in Rome he met with a certain opposition, whereupon he wrote the history of his family, showing that the Pecci of Carpineto were a branch of the Pecci of Siena, obliged to emigrate to the Papal States in the first half of the sixteenth century, under Clement VII, because they had sided with the Medici.

At the age of eight, together with his brother Giuseppe, aged ten, he was sent to study at the new Jesuit school in Viterbo, the present seminary. He remained there six years (1818-24), and gained that classical facility in the use of Latin and Italian afterwards justly admired in his official writings and his poems. Much credit for this is due to his teacher, Padre Leonardo Garibaldi. When, in 1824, the Collegio Romano was given back to the Jesuits, Gioacchino and his brother Giuseppe entered as students of humanities and rhetoric. At the end of his rhetoric course Gioacchino was chosen to deliver the address in Latin, and selected as his subject, “The Contrast between Pagan and Christian Rome” Not less successful was his three years’ course of philosophy and natural sciences.

He remained yet uncertain as to his calling, though it had been the wish of his mother that he should embrace the ecclesiastical state. Like many other young Romans of the period who aimed at a public career, he took up meanwhile the study of theology as well as canon and civil law. Among his professors were the famous theologian Perrone and the scripturist Patrizi. In 1832 he obtained the doctorate of theology, whereupon, after the difficulties referred to above, he asked and obtained admission to the Academy of Noble Ecclesiastics, and entered upon the study of canon and civil law at the Sapienza University. Thanks to his talents, and to the protection of Cardinals Sala and Paces., he was appointed domestic prelate by Gregory XVI in January, 1837, while still in minor orders, and in March of that year was made “referendario della Segnatura”, which office he soon exchanged for one in the Congregazione del Buon Governo, or Ministry of the Interior for the Pontifical States, of which his protector Cardinal Sala was at that time prefect. During the cholera epidemic in Rome he ably assisted Cardinal Sala in his duties as overseer of all the city hospitals. His zeal and ability convinced Cardinal Sala that Pecci was fitted for larger responsibilities, and he again urged him to enter the priesthood, hinting in addition that before long he might be promoted to a post where the priesthood would be necessary. Yielding to these solicitations, he was ordained priest December 31, 1837, by Cardinal Odeschalchi, Vicar of Rome, in the chapel of St. Stanislaus on the Quirinal. The post hinted at by Cardinal Sala was that of Delegate-or civil Governor of Benevento, a city subject to the Holy See but situated in the heart of the Kingdom of Naples. Its condition was very unsatisfactory; the brigands of the Neapolitan territory infested the country in great numbers, survivals of the Napoleonic Wars and the guerrilla of the Sanfedisti. Gregory XVI thought a young and energetic delegate necessary. Cardinal Lambruschini, secretary of state, and Cardinal Sala suggested the name of Msgr. Pecci, who set out for Benevento February 2, 1838. On his recovery from an attack of typhoid fever, he set to work to stamp out brigandage, and soon his vigilance, indomitable purpose, and fearless treatment of the nobles who protected the brigands and smugglers, pacified the whole province. Aided by the nuncio at Naples, Msgr. di Pietro, the youthful delegate drew up an agreement with the Naples police for united action against brigands. He also turned his attention to the roads and highways, and arranged for a more just distribution of taxes and duties, until then the same as those imposed by the invading French, and, though exorbitant, exacted with the greatest rigor. Meanwhile the Holy See and Naples were discussing the exchange of Benevento for a stretch of Neapolitan territory bordering on the Papal States. When Msgr. Pecci heard of this he memorialized the Holy See so strongly against it that the negotiations were broken off.

The results obtained in three years by the delegate at Benevento led Gregory XVI to entrust another delegation to him where a strong personality was required, though for very different reasons. He was first destined for Spoleto, but on July 17, 1841, he was sent to Perugia, a hotbed of the anti-papal revolutionary party. For three years he improved the material conditions of his territory and introduced a more expeditious and economical administration of justice. He also began a savings bank to assist small tradesmen and farmers with loans at a low rate of interest, reformed educational methods, and was otherwise active for the common welfare.

In January, 1843, he was appointed nuncio to Brussels, as successor of Msgr. Fornari, appointed nuncio at Paris. On February 19, he was consecrated titular Archbishop of Damiata by Cardinal Lambrusehini, and set out for his post. On his arrival he found rather critical conditions. The school question was warmly debated between the Catholic majority and the Liberal minority. He encouraged the Bishops and the laity in their struggle for Catholic schools, yet he was able to win the good will of the Court, not only of the pious Queen Louise, but also of King Leopold I, strongly Liberal in his views. The new nuncio succeeded in uniting the Catholics, and to him is owing the idea of a Belgian college in Rome (1844). He made a journey (1845) through Rhenish Prussia (Cologne, Mainz, Trier), and owing to his vigilance the schismatic agitation of the priest Ronge, on the occasion of the exposition of the Holy Coat of Trier in 1844, did not affect Belgium. Meanwhile the See of Perugia became vacant, and Gregory XVI, moved by the wishes of the Perugians and the needs of that city and district, appointed Msgr. Pecci Bishop of Perugia, retaining however the title of archbishop.

With a very flattering autograph letter from King Leopold, Msgr. Pecci left Brussels to spend a month in London and another in Paris. This brought him in touch with both courts, and afforded him opportunities for meeting many eminent men, among others Wiseman, afterwards cardinal. Rich in experience and in new ideas, and with greatly broadened views he returned to Rome on May 26, 1846, where he found the pope on his deathbed, so that he was unable to report to him. He made his solemn entry into Perugia July 26, 1846, where he remained for thirty-two years. Gregory XVI had intended to make him a. cardinal, but his death and the events that troubled the opening years of the pontificate of Pius IX postponed this honor until December 19, 1853. Pius IX desired to have him near his person, and repeatedly offered him a suburbicarian see, but Msgr. Pecci preferred Perugia, and perhaps was not in accord with Cardinal Antonelli. It is certainly untrue that Pius IX designedly left him in Perugia, much more untrue that he did so because fecci’s views were liberalistic and conciliatory. As Bishop of Perugia he sought chiefly to inculcate piety and knowledge of the truths of Faith.

He insisted that his catechize not only the young but the grown up; and for this purpose he wished one hour in the afternoon set apart on Sundays and feast days, thus forestalling one of the regulations laid down by Pius X in 1905 for the whole Church. He brought out a new edition of the diocesan catechism (1856), and for his clergy he wrote a practical guide for the exercise of the ministry 0857). He provided frequently for retreats and missions. After the Piedmontese occupation and the Suppression of the religious orders the number of priests was greatly diminished; to remedy this lack of ecclesiastical ministers, he established an association of diocesan missionaries ready to go wherever sent (1875). He sought to create a learned and virtuous clergy, and for this purpose spent much care on the material, moral, and scientific equipment of his seminary, which he called the apple of his eye. Between 1846 and 1850 he enlarged its buildings at considerable personal sacrifice, secured excellent professors, resided at examinations, and himself gave occasional instruction. He introduced the study of the philosophy and theology of St. Thomas, and in 1872 established an “Accademia di S. Tommaso”, which he had planned as far back as 1858.

In 1872 also he introduced the government standards for studies of the secondary schools and colleges. When the funds of the seminary were converted into state bonds, its revenues were seriously affected and this entailed new sacrifices on the bishop. With the exception of a few troublesome priests who relied on the protection of the new government, the discipline of the clergy was excellent. For the assistance of many priests impoverished by the confiscation of church funds, he instituted in 1873 the Society of S. Gioacchino, and for charitable works generally, conferences of St. Vincent de Paul. He remodeled many educational institutions for the young and began others, for the care of which he invited from Belgium nuns of the Sacred Heart and Brothers of Mercy. During his episcopate thirty-six new churches were built in the diocese. His charity and foresight worked marvels during the famine of 1854, consequent on the earthquake which laid waste a large part of Umbria. Throughout the political troubles of the period, he was a strong supporter of the temporal power of the Holy See, but he was careful to avoid anything that might give the new government pretext for further annoyances.

Shortly after his arrival in Perugia there occurred a popular commotion which his personal intervention succeeded in appeasing. In 1849, when bands of Garibaldians expelled from Rome were infesting the Umbrian hills, the Austrians under Prince Liechtenstein hastened to occupy Perugia, but Msgr. Pecci, realizing that this foreign occupation would only increase the irritation of the inhabitants, set out for the Austrian camp and succeeded in saving the town from occupation. In 1859 a few outlaws set up in Perugia a provisional government; when the cardinal heard that, few as they were, they were preparing to resist the pontifical troops advancing under Colonel Schmidt he wrote a generous letter to try and dissuade them from their mad purpose and to avoid a useless shedding of blood. Unfortunately they spurned his advice, and the result was the so-called “Massacre of Perugia” (June 20). In February, 1860, he wrote a pastoral letter on the necessity of the temporal power of the Holy See; but on September 14 of that year Perugia and Umbria were annexed to Piedmont. In vain he besought General Fanti not to bombard the town; and during the first years that followed the annexation he wrote, either in his own name or in the name of the bishops of Umbria, eighteen protests against the various laws and regulations of the new Government on ecclesiastical matters: against civil marriage, the suppression of the religious orders and the inhuman cruelty of their oppressors, the “Placet” and “Ex equatur” in ecclesiastical nominations, military service for ecclesiastics, and the confiscation of church property. But withal he was so cautious and prudent, in spite of his outspokenness, that he was never in serious difficulties with the civil power. Only once was he brought before the courts, and then he was acquitted.

In August 1877, on the death of Cardinal de Angelis, Pius IX appointed him camerlengo, so that he was obliged to reside in Rome. Pope Pius died February 7, 1878, and during his closing years the Liberal press had often insinuated that the Italian Government should take a hand in the conclave and occupy the Vatican. However the Russo-Turkish War and the sudden death of Victor Emmanuel II (January 9, 1878) distracted the attention of the Government, the conclave proceeded as usual, and after the three scrutinies Cardinal Pecci was elected by forty-four votes out of sixty-one.

Shortly before this he had written an inspiring pastoral to his flock on the Church and civilization. Ecclesiastical affairs were in a difficult and tangled state. Pius IX, it is true, had won for the papacy the love and veneration of Christendom, and even the admiration of its adversaries. But, though inwardly strengthened, its relations with the civil powers had either ceased or were far from cordial. But the fine diplomatic tact of Leo succeeded in staving off ruptures, in smoothing over difficulties, and in establishing good relations with almost all the powers.

Throughout his entire pontificate he was able to keep on good terms with France, and he pledged himself to its Government that he would call on all Catholics to accept the Republic. But in spite of his efforts very few monarchists listened to him, and towards the end of his life he beheld the coming failure of his French policy, though he was spared the pain of witnessing the final catastrophe which not even he could have averted. It was to Leo that France owed her alliance with Russia; in this way he offset the Triple Alliance, hoped to ward off impending conflicts, and expected friendly assistance for the solution of the Roman question. With Germany he was more fortunate. On the very day of his election, when notifying the emperor of the event, he expressed the hope of seeing relations with the German Government reestablished, and, though the emperor’s reply was coldly civil, the ice was broken. Soon Bismarck, unable to govern with the Liberals, to win whose favor he had started the Kulturkampf (q.v.), found he needed the center Party, or Catholics, and was willing to come to terms. As early as 1878 negotiations began at Kissingen between Bismarck and Aloisi-Masella the nuncio to Munich; they were carried a step farther at Venice between the nuncio Jacobini and Prince von Reuss; soon after this some of the Prussian laws against the Church were relaxed. From about 1883 bishops began to be appointed to various sees, and some of the exiled bishops were allowed to return. By 1884 diplomatic relations were renewed, and in 1887 a modus vivendi between Church and State was brought about. In 1885 the question of the Caroline Islands arose, and Bismarck proposed that Pope Leo should arbitrate between Germany and Spain. The good feeling with Germany found expression in the three visits paid Leo by William II (1888, 1893, and 1903), whose father also, when crown prince (1883), had visited the Vatican. As a sort of quid pro quo Bismarck thought the pope ought to use his authority to prevent the Catholics from opposing some of his political schemes. Only once did Leo interfere in a parliamentary question, and then his advice was followed. In 1880 relations with the Belgian Government were again broken off a propos of the school question, on the pretext that the pope was lending himself to duplicity, encouraging the bishops to resist, and pretending to the Government that he was urging moderation.. As a matter of fact, the suppression of the Belgian embassy to the Vatican had been settled on before the school question arose. In 1885 the new Catholic Government restored it. During Pope Leo’s pontificate the condition of the Church in Switzerland improved somewhat, especially in the Ticino, in Aargau, and in Basle. In Russia, Soloviev’s attempt on Alexander II (April 14, 1879) and the silver jubilee of that czar’s reign (1880) gave the pope an opportunity to attempt a rapprochement. But it was not until after Alexander III came to the throne (1883) that an agreement was reached, by which a few episcopal sees were tolerated and some of the more stringent laws against the Catholic clergy slightly relaxed. But when, in 1884, Leo consented to present to the czar a petition from the Ruthenian Catholics against the oppression they had to suffer, the persecution only increased in bitterness. In the last year of Alexander III (May, 1894) diplomatic relations were reestablished. On the day of his election, Leo had expressed to this emperor the wish to see diplomatic relations restored; Alexander, like William, though more warmly, answered in a non-committal manner. In the meantime Leo was careful to exhort the Poles under Russian domination to be loyal subjects.

Among the acts of Leo XIII that affected in a particular way the English-speaking world may be mentioned: for England, the elevation of John Henry Newman to the cardinalate (1879), the “Romanos. Pontifices” of 1881 concerning the relations of the hierarchy and the regular clergy, the beatification (1886) of fifty English martyrs, the celebration of the thirteenth centenary of St. Gregory the Great, Apostle of England (1891), the Encyclicals “Ad Anglos” Basilica of St. John Lateran, Rome of 1895, on the return to Catholic unity, and the “Apostolicae Curse” of 1896, on the non-validity of the Anglican orders. He restored the Scotch hierarchy in 1878, and in 1898 addressed to the Scotch a very touching letter. In English India Pope Leo established the hierarchy in 1886, and regulated there longstanding conflicts with the Portuguese authorities. In 1903 King Edward VII paid him a visit at the Vatican. The Irish Church experienced his pastoral solicitude on many occasions. His letter to Archbishop McCabe of Dublin (1881), the elevation of the same prelate to the cardinalate in 1882, the calling of the Irish bishops to Rome in 1885, the decree of the Holy Office (April 13, 1888) on the plan of campaign and boycotting, and the subsequent Encyclical of 24.June, 1888, to the Irish hierarchy represent in part his fatherly concern for the Irish people, however diverse the feelings they aroused at the height of the land agitation.

The United States at all times attracted the attention and admiration of Pope Leo. He confirmed the decrees of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore (1884), and raised to the cardinalate Archbishop Gibbons of that city (1886). His favorable action (1888), at the instance of Cardinal Gibbons, towards the Knights of Labor won him general approval. In 1889 he sent a papal delegate, Monsignor Satollil to represent him at Washington on the occasion of the foundation of the Catholic University of America.

The Apostolic Delegation at Washington was founded in 1892; in the same year appeared his Encyclical on Christopher Columbus. In 1893 he participated in the Chicago Exposition held to commemorate the fourth centenary of the discovery of America; this he did by the loan of valuable relics, and by sending Monsignor Satolli to represent him. In 1895 he addressed to the hierarchy of the United States his memorable Encyclical “Longinqua Oceani Spatia”; in 1898 appeared his letter “Testem Benevolentise” to Cardinal Gibbons on “Americanism”; and in 1902 his admirable letter to the American hierarchy in response to their congratulations on his pontifical jubilee. In Canada he confirmed the agreement made with the Province of Quebec (1889) for the settlement of the Jesuit Estates question, and in 1897 sent Monsignor Merry del Val to treat in his name with the Government concerning the obnoxious Manitoba School Law. His name will also long be held in benediction in South America for the First Plenary Council of Latin America, held at Rome (1899), and for his noble Encyclical to the bishops of Brazil on the abolition of slavery (1888).

In Portugal the Government ceased to support the Goan schism, and in 1886 a concordat was drawn up. Concordats with Montenegro (1886) and Colombia (1887) followed. The Sultan of Turkey, the Shah of Persia, the Emperors of Japan and of China (1885), and the Negus of Abyssinia, Menelik, sent him royal gifts and received gifts from him in return. His charitable intervention with the negus in favor of the Italians taken prisoners at the unlucky battle of Adna (1898) failed owing to the attitude taken by those who ought to have been most grateful. He was not successful in establishing direct diplomatic relations with the Sublime Porte and with China, owing to the jealousy of France and her fear of losing the protectorate over Christians. During the negotiations concerning church property in the Philippines, Mr. Taft, later President of the United States, had an opportunity of admiring the pope’s great qualities, as he himself declared on a memorable occasion. With regard to the Kingdom of Italy, Leo XIII maintained Pius IX’s attitude of protest, thus confirming the ideas he had expressed in his pastoral of 1860. He desired complete independence for the Holy See, and consequently its restoration as a real sovereignty. Repeatedly, when distressing incidents took place in Rome, he sent notes to the various governments pointing out the intolerable position in which the Holy See was placed through its subjection to a hostile power. For the same reason he upheld the “Non expedit”, or prohibition against Italian Catholics taking part in political elections. His idea was that once the Catholics abstained from voting, the subversive elements in the country would get the upper hand and the Italian Government be obliged to come to terms with the Holy See. Events proved he was mistaken, and the idea was abandoned by Pius X. At one time, however, “officious” negotiations were kept up between the Holy See and the Italian Government through the agency of Monsignor Carlin, Prefect of the Vatican Library and a great friend of Crispi. But it is not known on what lines they were conducted. On Crispi’s part there could have been no question of ceding any territory to the Holy See. France, moreover, then irritated against Italy because of the Triple Alliance, and fearing that any rapprochement between the Vatican and the Quirinal would serve to increase her rival’s prestige, interfered and forced Leo to break off the aforesaid negotiations by threatening to renew hostilities against the Church in France. The death of Monsignor Carini shortly after this (June 25, 1895) gave rise to the senseless rumor that he had been poisoned. Pope Leo was no less active concerning the interior life of the Church. To increase the piety of the faithful, he recommended in 1882 the Third Order of St. Francis, whose rules in 1883 he wisely modified; he instituted the feast of the Holy Family, and desired societies in its honor to be founded everywhere (1892); many of his encyclicals preach the benefits of the Rosary; and he favored greatly devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Under Leo the Catholic Faith made great progress; during his pontificate two hundred and forty-eight episcopal or archiepiscopal sees were created, and forty-eight vicariates or prefectures Apostolic. Catholics of Oriental rites were objects of special attention; he had the good fortune to see the end of the schism which arose in 1870 between the Uniat Armenians and ended in 1879 by the conversion of Msgr. Kupelian and other schismatical bishops. He founded a college at Rome for Armenian ecclesiastical students (1884), and by dividing the college of S. Atanasio he was able to give the Ruthenians a college of their own; already in 1882 he had reformed the Ruthenian Order of St. Basil; for the Chaldeans he founded at Mossul a seminary of which the Dominicans have charge. In a memorable encyclical of 1897 he appealed to all the schismatics of the East, inviting them to return to the Universal Church, and laying down rules for governing the relations between the various rites in countries of mixed rites. Even among the Copts his efforts at reunion made headway.

The ecclesiastical sciences found a generous patron in Pope Leo. His Encyclical “Aeterni Patris” (1880) recommended the study of Scholastic philosophy, especially that of St. Thomas Aquinas, but he did not advise a servile study. In Rome he established the Apollinare College, a higher institute for the Latin, Greek, and Italian classics. At his suggestion a Bohemian college was founded at Rome. At Anagni he founded and entrusted to the Jesuits a college for all the dioceses of the Roman Campagna, on which are modeled the provincial or “regional” seminaries desired by Pius X. Historical scholars are indebted to him for the opening of the Vatican Archives (1883), on which occasion he published a splendid encyclical on the importance of historical studies, in which he declares that the Church has nothing to fear from historical truth. For the administration of the Vatican Archives and Library he called on eminent scholars (Hergenrother, Denifle, Ehrle; repeatedly he tried to obtain Janssen, but the latter declined, as he was eager to finish his “History of the German People”). For the convenience of students of the archives and the library he established a consulting library. The Vatican Observatory is also one of the glories of Pope Leo XIII. To excite Catholic students to rival non-Catholics in the study of the Scriptures, and at the same time to guide their studies, he published the “Providentissums Deus” (1893), which won the admiration even of Protestants, and in 1902 he appointed a Biblical Commission. Also, to guard against the dangers of the new style of apologetics founded on Kantism and now known as Modernism (q.v.), he warned in 1899 the French clergy (Encycl. “Au Milieu”), and before that, in a Brief addressed to Cardinal Gibbons, he pointed out the dangers of certain doctrines to which had been given the name of “Americanism” (January 22, 1899). In the Brief “Apostolicae Curae” (1896) he definitively decided against the validity of Anglican Orders. In several other memorable encyclicals he treated of the most serious questions affecting modern society. They are models of classical style, clearness of statement, and convincing logic. The most important are: “Arcanum divine sapientiae” (1880) on Christian marriage; “Diuturnum illud” (1881), and “Immoraale Dei” (1885) on Christianity as the foundation of political life; “Sapientiae christianae” (1890) on the duties of a Christian citizen; “Libertas” (1888) on the real meaning of liberty; “Humanum genus” (1884) against Freemasonry (he also issued other documents bearing on this subject).

Civilization owes much to Leo for his stand on the social question. As early as 1878, in his encyclical on the equality of all men, he attacked the fundamental error of Socialism. The Encyclical “Rerum novarum” (May 18, 1891) set forth with profound erudition the Christian principles bearing on the relations between capital and labor, and it gave a vigorous impulse to the social movement along Christian lines. In Italy, especially, an intense, well-organized movement began; but gradually dissensions broke out, some leaning too much towards Socialism and giving to the words “Christian Democracy” a political meaning, while others erred by going to the opposite extreme. In 1901 appeared the Encyclical “Graves de Communi”, destined to settle the controverted points. The “Catholic Action” movement in Italy was reorganized, and to the “Opera dei Congressi” was added a second group that took for its watchword economic-social action. Unfortunately this latter did not last long, and Pius X had to create a new party which has not yet overcome its internal difficulties.

Under Leo the religious orders developed wonderfully; new orders were founded, older ones increased, and in a short time made up for the losses occasioned by the unjust spoliation they had been subjected to. Along every line of religious and educational activity they have proved no small factor in the awakening and strengthening of the Christian life of the whole country. For their better guidance wise constitutions were issued; reforms were made; orders such as the Franciscans and Cistercians, which in times past had divided off into sections, were once more united; and the Benedictines were given an abbot-primate, who resides at St. Anselm’s College, founded in Rome under the auspices of Pope Leo (1883). Rules were laid down concerning members of religious orders who became secularized.

In canon law Pope Leo made no radical change, yet no part of it escaped his vigilance, and opportune modifications were made as the needs of the times required. On the whole his pontificate of twenty-five years was certainly, in external success one of the most brilliant. It is true the general peace between nations favored it. The people were tired of that anticlericalism which had led governments to forget their real purpose, i.e. the well-being of the governed; and, on the other hand, prudent statesmen feared excessive catering to the elements subversive of society. Leo himself used every endeavor to avoid friction. His three jubilees (the golden jubilees of his priesthood and of his episcopate, and the silver jubilee of his pontificate) showed how wide was the popular sympathy for him. Moreover, his appearance either at Vatican receptions or in St. Peter’s was always a signal for outbursts of enthusiasm. Leo was far from robust in health, but the methodical regularity of his life stood him in good stead. He was a tireless worker, and always exacted more than ordinary effort from those who worked with him. The conditions of the Holy See did not permit him to do much for art, but he renewed the apse of the Lateran Basilica, rebuilt its presbytery, and in the Vatican caused a few halls to be painted.

U. BENIGNI