Christendom. In its wider sense this term is used to describe the part of the world which is inhabited by Christians, as Germany in the Middle Ages was the country inhabited by Germans. The word will be taken in this quantitative sense in the article Religions (q.v.) in comparing the extent of Christendom with that of Paganism or of Islam. But there is a narrower sense in which Christendom stands for a polity as well as a religion, for a nation as well as for a people. Christendom in this sense was an ideal which inspired and dignified many centuries of history and which has not yet altogether lost its power over the minds of men.

The foundations of a Christian polity are to be found in the traditions of the Jewish theocracy softened and broadened by Christian cosmopolitanism, in the completeness with which Christian principles were applied to the whole of life, in the aloofness of the Christian communities from the world around them, and in the hierarchical organization of the clergy. The conflict between the new religion and the Roman Empire was due partly to the very thoroughness of the Christian system and it naturally emphasized the distinction between this new society and the old state. Thus when Constantine proclaimed the Peace of the Church he might almost be described as signing a treaty between two powers. From that Peace to the time of the Barbarian inroads into the West, Christendom was all but conterminous with the Roman Empire, and it might be thought that the ideal of a Christian nation was then at least realized. The legal privileges which were granted to the bishops from the first and which tended to increase, the protection given to the churches and the property of the clergy, and the principle admitted by the emperors, that questions of faith were to be freely decided by the bishops, all these concessions seemed to show that the empire had become positively as well as negatively Christian. To St. Ambrose and the bishops of the fourth century the destruction of the empire seemed almost incredible except as a phase of the final catastrophe, and the system which prevailed in the days of Theodosius seemed almost the ideal Christian polity. Yet there was about it much that fell short of the ideal of Christendom. In many ways, as a contemporary bishop expressed it, “the church was in the empire, not the empire in the church”. The traditions of Roman imperialism were too strong to be easily mitigated. Constantine, though not even a catechumen, in a sense, at least, presided over the Council of Nica and the “Divinity” of his son Constantius, though formally observing the rule that decisions of faith belonged to the bishops, was able to exert such pressure upon them that at one time not a single strictly orthodox bishop was left in the occupation of his see. The officious interference of a theologian emperor was more dangerous to the Church than the hostility of Julian, his successor. But the wish to dominate in every sphere was not the only relic of pagan Rome. Though the emperor was no longer pontifex maximus and the statue of Victory was removed from the senate house, though Theodosius decreed the final closing of the temples and put an end to pagan public worship, the ancient world was not really converted, it was hardly a catechumen. In philosophy, literature, and art it clung to the old models and reproduced them in a debased form. Pagan civilization had not been renewed in Christ. Such a rebirth demanded Christians of a simpler character and a more spontaneous vigour than the inhabitants of the degenerate empire. The formation of Christendom was to be the work of a new generation of nations, baptized in their infancy and receiving even the message of the ancient world from the lips of Christian teachers.

But it was to be long before the great future hidden in the Barbarian invasions was to become manifest. At their first irruption the influence of the Teutonic tribes was only destructive; the Christian polity seemed to be perishing with the empire. The Church, however, as a spiritual power survived and mitigated even the fury of the Barbarian, for the helpless population of Rome found a refuge in the churches during the sack of the city by Alaric in 410. The distinction between Church and empire, which this disaster illustrated, was emphasized by the accusations brought against the patriotism of the Christians and by St. Augustine’s reply in his “De Civitate Dei”. He develops in this encyclopaedic treatise the idea of the two kingdoms or societies (city, except in a very metaphorical sense, is too narrow to be an adequate translation of civitas), the Kingdom of God consisting of His friends in this world and the next, whether men or angels, while the earthly kingdom is that of His enemies. These two kingdoms have existed since the fall of the angels, but in a more limited sense and in relation to the Christian dispensation, the Church is spoken of as God‘s kingdom on earth while the Roman Empire is all but identified with the civitas terrena; not altogether, however, because the civil power, in securing peace for that part of the heavenly kingdom which is on its earthly pilgrimage, receives some kind of Divine sanction. We might, perhaps, have expected, now that the empire was Christian, that St. Augustine would have looked forward to a new civitas terrena reconciled and united to the civitas Del; but this prophetic vision of the future was prevented, it may be, by the prevalent opinion, that the world was near its end. The “De Civitate”, however, which had a commanding influence in the Middle Ages, helped to form the ideal of Christendom by the development which it gave to the idea of the kingdom of God upon earth, its past history, its dignity, and universality.

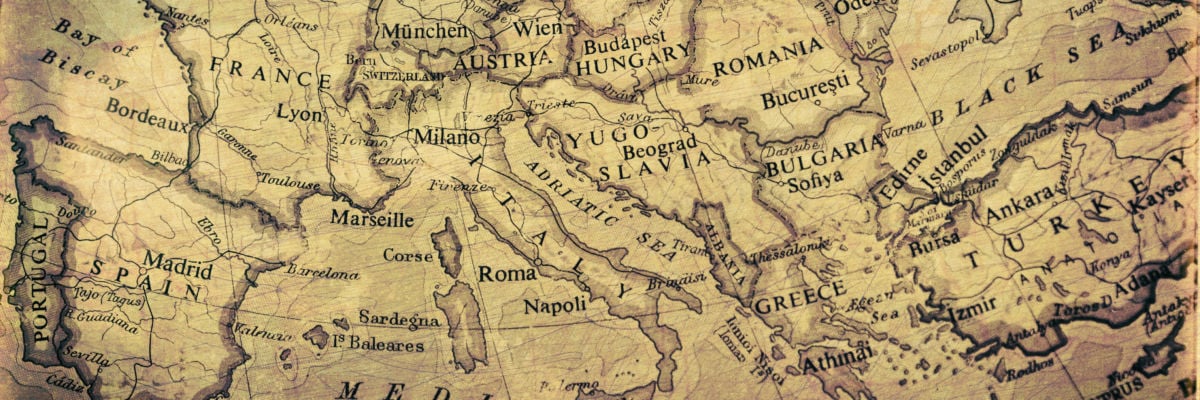

From the fifth century till the days of Charles the Great (see Charlemagne) there was no effectual political unity in the West, and the Church had no civil counterpart. But Charles’ dominions extended from the Elbe to the Ebro and from Brittany to Belgrade; there was but little of Western Christendom which they did not include. Ireland and the South of Italy were the only parts of it which his power or his influence did not reach. Over the territories actually comprised in his empire he exercised a real control, administrative and legislative, as well as military. But the Carlovingian empire was far more than a mere political federation: it was a period of renewal and reorganization in nearly every sphere of social life. It was spiritual, perhaps, even more than political. In war conversion went hand in hand with victory; in peace Charles ruled through bishops as effectively as through counts; his active solicitude extended to the reform and education of the clergy, the promotion of learning, the revival of the Benedictine Rule, to the arts, to the liturgy and even the doctrines of the Church. In the West Christendom became a temporal polity and a society as well as a Church, and the empire of Charles, brief though its existence proved to be, remained for many centuries an ideal and therefore a power. Yet the Carlovingian civilization was in most cases a return to late Roman models. Originality is not its characteristic. Charles’ favorite church at Aachen is supported on the columns which he sent for from the ruined temples of Italy. Even in his relations with the Church he would have found the closest precedents for his policy in the attitude of Constantine or even perhaps of Justinian. Great as was his respect for the successor of St. Peter, he claimed for himself a masterful share in the administration of matters ecclesiastical: he could write, even before his coronation as emperor, to Pope Leo III, “My part is to defend the Church by force of arms from external attacks and to secure her internally through the establishment of the Catholic faith; your part is to render us the assistance of prayer”. Still every step forward has usually begun with a return to the past; it is thus that the artist or the statesman learns his craft. If the Carlovingian system had lasted, no doubt much that was new would have been developed, and even under Charles’s successor the spiritual and temporal powers were placed on a more equal and more appropriate footing. But Charles was too great for his age; his work was premature. The political bond was too weak to prevail over tribal loyalty and Teutonic particularism. Disorder and disruption would have broken up Carlovingian civilization even if Northman, Saracen, and Hungarian had not come to plunge Europe once more into anarchy.

During the tenth century the work of moral and political reconstruction was slowly carried on by the Church and feudalism; in the eleventh came that struggle between these two creative factors of the new Europe which saved the Church from absorption into feudalism. This century opened with what was, perhaps, the most hopeful attempt, after Charles the Great, to give the medieval empire a really universal character. The revived empire of Otto I in the middle of the tenth century had been but an imperfect copy of its Carlovingian model. It was much more limited geographically, as it included only Germany, its dependent states to the east, and Italy; it was limited also in its interests, for Otto left to the Church nearly all those spheres of ecclesiastical, educational, literary, and artistic activity for which Charles had done so much. But Otto’s grandson, the boy-emperor Otto III, “magnum quoddam et improbabile cogitans”, as a contemporary expressed it, attempted to make the empire less German, less military, more Roman, more universal, and more of a spiritual force. He was in intimate alliance with the Holy See, and with almost startling originality he established in Rome the first German and then the first French pope. He seems to have realized the truth that it was only by leaning on and developing the religious aspect of the empire that he could hope at that stage of history to make its influence universal in the West. Europe was so unformed politically that the long reign of a wise and determined emperor backed up by the Church might perhaps have changed its future history, have brought together into one broad and rather indefinite channel the small but already divergent streams of national tendencies, and built up Europe on the basis of a Christian federalism. But Otto, mirabile mundi, died at the age of twenty-two, and the dream of a Christian empire faded away. Never again did a successor of his make a serious attempt to throw off his German character and to make the sphere of his rule conterminous with Christendom. Fascinating as is the theory of the Holy Roman Empire, and great as was its influence on history and speculation, it was always something of a sham. It claimed in political matters a sphere of action as wide as that of the popes in things spiritual; but, unlike the spiritual, this political plena potestas was never admitted. Even before the War of Investitures and the First Crusade had made so wide a breach in the imperial prestige, an Abbot of Dijon of Italian origin could contrast the still enduring unity of the Church with the disruption of the civil power. The empire is generally held to have reached its zenith in the middle of the eleventh century, but that is not the century in which we find the ideal of a united Christendom nearest its realization.

Political unity in the West was never restored after the fall of the Carlovingian Empire, religious unity lasted till the Reformation, but in the twelfth century we find, in addition, a very large measure of what may compendiously be called “social unity”. Before that time isolation, disorder, and the predominance of feudalism had kept men apart; after it the development of national distinctions was to have something of the same effect. The twelfth century is therefore the period in which Christian cosmopolitanism can best be studied. The Church was naturally the chief unifying force; in the darkest days she had preached the same gospel to Frank, Saxon, and Gallo-Roman, and her organization had been, at critical moments when the civil power had almost sunk under the flood, the only bond which linked together the populations of the West. The opening century found the Church in the midst of that Hildebrandine movement, in favor of clerical celibacy and against simony, which was necessary to save the spiritual character of the clergy from being obliterated by too close a contact with temporal administration and the material ambitions of feudal society. The reform, though its center was at Rome, was a European movement. Its forerunners had been found in the monasteries of Burgundy and among the students of canon law in the Rhine cities; at the height of the struggle its leaders included Italians, Lorrainers, Frenchmen, and a German monastic revival. When Paschal II showed signs of faltering, the movement was carried on almost in spite of him by the zeal of French reformers. Even Spain, England, and Denmark caught the saving infection, and the eventual settlement between Church and empire was foreshadowed in the concordat, devised probably by a French canonist, which was agreed to by St. Anselm and Henry I. Thus did all the nations which were to be have their share in the victory of Hildebrandine principles, and there was roused throughout the West a revival of the spiritual life. The ideals of the clergy were raised, or rather they acquired strength and confidence to pursue ideals which they had always, though despairingly, acknowledged. This crusade against selfishness, passion, and weakness brought together the clergy of the West, as the attack on more material foes united its peoples, and as a consequence the ecclesiastical body in the twelfth century is a real society almost contemptuous of political or racial frontiers. We find Frenchmen and an Englishman in the chair of St. Peter; an Italian, St. Anselm, at Canterbury; a Savoyard, St. Hugh, at Lincoln; an English John of Salisbury at Chartres: instances such as those could be multiplied almost indefinitely. In medieval Latin this vast society possessed a language suited to the varied wants of the age, and it is as living as any vernacular if we read it in a letter of St. Anselm, a sermon of St. Bernard, a poem of Adam of St. Victor, the “Polycraticus” of John of Salisbury, an assize of Henry II, the desultory chronicle of Ordericus Vitalis, or the finished history of William of Tyre. It was a language which might have had a greater literature if the less simple amongst those who wrote had not been continually harking back to classical models.

The spirit of Catholicity in the Church was guarded and prompted by the ever increasing power of the popes. The days when the Holy See had had to be rescued by the emperors from the petty and passionate Roman nobility must have seemed far off, and the most definite result of the War of Investitures was a second liberation, the conquest of the complete independence of papal elections. Never was the papal power in Europe so great as in the years between the end of that war in 1122 and the great disaster of the Second Crusade. Besides being the guardian of the Faith, the papacy was fast becoming the central court of Christendom. For close on two centuries, from Nicholas I to Leo IX in the middle of the eleventh century, the plenary powers of the pope had been but exceptionally exercised north of the Alps, though they had been acknowledged in principle, but in this most legal of centuries the exercise of papal jurisdiction becomes habitual. The Curia was treated as a court of first instance as well as a court of appeal. Hardly any subject was too small or too local to be referred to Rome: the pope, for instance, decided whether or not the Duke of Lorraine might have a castle within four miles of Toul. Papal legates might be met on all the highways of Christendom; papal courts sat in every land. Canon law grew fast, and the “Decretum” of Gratian, about the middle of the century, though it was not an authoritative collection, provided legates and judges with an admirable synthesis of papal pronouncements. St. Bernard was much troubled at the amount of legal business which poured in upon the pope; it must, he considered, interfere with the more spiritual duties of his high office. But the movement was irresistible; the papacy had become de facto the center of a vast Christian nation. The empire was, as we have seen, out of court. It was in the papacy that Christendom, a temporal as well as a spiritual society, found its head in temporal and spiritual things alike.

After the faith and the hierarchy of the Church the monastic orders have usually formed the strongest bond of Catholic union, and in the twelfth century the monastic spirit was full of life. In the previous epoch the Cluniac Benedictines had played an essential part in the work of reconstruction; but life was now more complicated, and monasticism took many forms. The contemplative spirit of the old hermits inspired the Carthusian foundation of St. Bruno, “the only ancient order which has never been reformed and never required reforming”, the increased demand for parish work led to the revival of regular canons, and in part to the foundation of the Premonstratensians, the Crusades produced the military orders, while in the Cistercians the new spiritual fervor with its ascetical and mystical tendencies found appropriate expression. Seldom has a new order spread with such rapidity throughout Europe as these white Benedictines, and St. Bernard, their great representative, is the most marvellous instance of the power of a single man, without official position, over all classes and different nations. The settlement of a disputed papal election practically depended on his verdict, he appeased the feuds of German noble families and reconciled Italian cities, he led one emperor to the South of Italy and sent another on a crusade to the East; more wonderful still, single-handed he persuaded the Roman people to forsake the antipope. Though not the originator, he was the motive power of the Second Crusade, and his eloquence seemed as persuasive in the Rhine cities as in Burgundy, and as successful in saving the Jews from the fanaticism of the crusaders as in rousing the crusading spirit.

Besides the Church and its many activities, there were other forces at work, other expressions of the energy of youthful Christendom which must at least be enumerated. The twelfth-century renaissance was a rapid development of what may be called Franco-Norman civilization. France, if the name is given a comprehensive meaning, had conquered England and South Italy, had brought about the Crusades, and had helped the papacy to victory over the empire. It was in France that the new monastic movements took their rise, and the intellectual movement as well. The University of Paris was the university of Christendom, and the problems stated by the Breton Abelard excited the curiosity and the enthusiasm of young men from every country. French was spoken nearly as widely as Latin, and the medieval epic, the romances of the Arthurian legend, and the lyrics of the troubadours, the three most characteristic forms of medieval vernacular literature, all were developed amongst men who spoke one of the dialects of French. Politically the Franco-Norman world was divided between Plantagenet, Capetian, and the princes of the South, and the personality of Frederick Barbarossa gave a splendor to German politics, but intellectually and socially French civilization dominated Europe. It was, however, a supremacy which lay in the rapidity and logical thoroughness with which she expressed ideas common to the whole West. The development of Gothic architecture in England was almost parallel to the French, the epic and the Arthurian legend found a congenial soil in Germany, and the lyrical poetry of Italy was almost a younger sister to that of Provence. The same spirit seemed to be abroad from Scotland to Palermo, and the Christians of the West must have felt that they were indeed citizens of a great city.

For this sense of a common Christendom was not confined to the clergy or the knightly and baronial classes. The peasantry and the town-population had much improved their economic and legal positions since the beginning of the eleventh century; they had also profited by the education of action and experience. In the movement for the Truce of God, in the Hildebrandine reform, in the Crusades, in all these struggles of a crowded age, “the holy people of God” had taken a prominent part; all had increased their self-confidence, all had drawn them closer to the clergy and to one another. Though the aim of the Hildebrandine reform was to preserve the distinctive features of the priestly life, it had not formed the clergy into a caste. Gregory VII had appealed to the laity, and the reformers found among the people allies most enthusiastic, at times indeed fanatical and cruel. The Crusades, too, had consecrated the devotion of the poor pilgrims as well as knightly valor. At one moment, when the leaders had forgotten the Holy City for the sake of Syrian castles, it was the zeal of the poor that alone saved the fortunes of the expedition. In the other movements of the time clergy and people were often united, and municipal liberties, at least in their earlier stages, found a support in the Church. Alexander III, the greatest pope of the century, was allied with the Lombard republics in their struggle with Frederick Barbarossa, the greatest of its emperors. It is at least probable that since the early ages of the Church, clergy and laity have never been so united as in this century. Few medieval saints have excited so much universal and popular enthusiasm as St. Thomas of Canterbury, a martyr for the rights of the Church and the clergy, and the pilgrims who thronged to Canterbury from all parts of Christendom are perhaps the best evidence of the union between people and clergy, and between the different nations of the West.

The pontificate of Innocent III, which began before the close of the twelfth century, was the climax of this period of Christian cosmopolitanism. It illustrates both the splendor of the ideal and the increasing difficulty of realizing it. Few popes have had nobler aims than Innocent, few have been more favored by nature and circumstance or have been apparently more successful. He was enabled to put himself at the head of a national movement in Italy, to govern Rome, where his predecessors had been weakest, to compel the King of France to respect the rights of marriage and the King of England those of the Church, to help in the success of two papalist candidates to the empire, and to see a crusade sail for the East. These are but some of the successes of his reign, yet it is impossible to study the fortunes of his pontificate without observing that nearly every one of his victories is marked by the signs of ultimate failure. Of the two emperors whom he helped to the throne, the first repudiated all his engagements and declared open war upon him in Italy, the second was that Frederick II who was to be the most thoroughgoing foe of the papacy. The homage which Innocent won from King John contributed in a later generation to embitter the relations between England and the Holy See. In his Italian policy, disinterested as it was, can be traced the first beginnings of future evils; the political power he had acquired led to the first case of nepotism and to the first appeal to a French noble for help in the South of Italy. He lost control over both the religious campaigns which he set in motion, for he endeavored unsuccessfully to protect Raymond of Toulouse from the Albigensian crusaders and to prevent the Venetians diverting the Fourth Crusade from Jerusalem to Constantinople.

That so great a pope should meet with failures so signal was significant of the change coming over Europe. The control over temporal and even ecclesiastical matters was slipping away from the head of Christendom, though the great personality of Innocent and the successful war waged by his successors against the empire might disguise the fact from contemporaries. In the fourteenth century the national wars, the Great Schism, the unimpeded progress of the Turks, these were all witnesses to the divisions of Christendom. For a moment, at the time of the Council of Constance in 1414, there seemed to be a rally; the Christian society appeared to, be drawing together again in order to put an end to the schism and to reform the Church; but as a matter of fact that council was the first of European congresses, a meeting of national delegates rather than a parliament of Christendom. The history of this change from the Christendom of the twelfth century to the nations of the Reformation epoch, is the history of the later Middle Ages. It is possible, however, to disentangle some of the elements of this complicated process of disintegration.

To the modern student, who is wise after the event, it is clear by the eleventh century that the Europe of the future is not going to be built up politically as an empire, and that the ultimate development of some form of national state is assured. The Church, though she might have preserved a large measure of social unity and linked the nations together, could never have formed a permanent, universal state, for Christianity is not, like Islam, a political system. Politically, there seem but two alternatives: empire or nations. Indeed the roots of nationality can be traced deep down in geographical and racial differences and in the varying degrees in which the Teutonic invaders of the Roman Empire coalesced with its old inhabitants. In the twelfth century, though the sense of a common Christianity is the predominant characteristic of the age, the development of national distinctions proceeded apace. Germany was long to regret the glories of the reign of Frederick Barbarossa, yet even his power failed to level the Alps politically and to overcome the still hardly conscious nationalism of the Lombard cities. The social and intellectual influence which France had exerted in the middle of the century began under Philip Augustus to take a political form; while in England conquerors and conquered were fast amalgamating, and a national feeling, fostered by insular position, had grown up, though it was concealed for the moment by the extent of the Angevin Empire and the foreign interests of Henry II and Richard I. This empire broke into pieces under John, and, after an interval of weakness and hesitation, England appears in the reign of Edward I as the country where nationality had most rapidly developed. Elsewhere, too, the process continued. The personality of St. Louis gave to the French monarchy a halo comparable to the spiritual character which was to cling for so many centuries to the Holy Roman Empire. The fall of the Hohenstauffen decided finally what had long threatened, that Germany was to be not a State, but at any rate a nation severed from Italy, and that Italy itself was to live its own turbulent city life so fruitful in war, in tyranny, in saints, and in works of art.

Meanwhile the new monarchies of the West became self-conscious through their lawyers. Secular law in the twelfth century had given its support to the civil power, but it had been overshadowed, on the whole, by the great development of canon law. Towards the close of the thirteenth it had its revenge as the ally of the national sovereigns. Edward I was both one of the most legal and one of the most powerful of English kings, yet in his case legal absolutism was mitigated by customary law. In France the enigmatic figure of Philip the Fair was half-concealed by his legist ministers, men who combined a radical anti-clericalism, ready to go any lengths, with the most frank acknowledgment of the absolute power of the sovereign. It is an instance of the irony of history that Edward and Philip should be the contemporaries of Boniface VIII, the boldest assertor of papal supremacy. The probable explanation is that the recent victory over the empire misled the papalist writers and perhaps the popes themselves. The disappearance of the Hohenstauffen seemed to leave the papacy an undisputed supremacy in the Christian world. It had been the practice to speak of the spiritual and temporal powers in terms of pope and emperor, and it was long before it was realized, at least on the papal side, that the civil power, defeated as emperor, had returned to the attack with more aggressive vigour as the Monarchy and the State. The papal-imperial controversy continued, though with increasing unreality, when the pope was at Avignon, and the emperor was Louis of Bavaria, and little effort was made to adapt to the new conditions the older theory of the coordinate powers of Church and State, both of immediate Divine origin but differing in dignity.

The struggle between Boniface and Philip culminated in the outrage of Anagni, where Nogaret, the French lawyer, struck the aged pope. It was a brutal act, disgraceful only to the perpetrator. Unfortunately, it was followed by the migration, a few years later, of the papal court to the prison-palace of Avignon. This premature development of French absolutism was followed by years of war and anarchy; but from her misfortunes France rose up a consolidated monarchy. In England, aristocratic misrule and some forty years of intermittent civil war produced the same result. In Spain, and even in the German and Scandinavian principalities and kingdoms, different causes tended in the same direction. Thus grew up those monarchies, powerful at home, jealous of foreign interference, which contributed so much to the Reformation.

While in the political sphere nations were drawing apart, in the social sphere the Church was losing much of her influence on the thoughts of men. Some of this loss was perhaps inevitable. New interests were springing up on every side with the growth of wealth, of education, and of the complexity of life, new professions, other than that of arms, were being opened to the educated laity. Religion could hardly expect to keep the hold she had exercised on the outward lives of Christians. Meanwhile the improvement of secular law would in time render unnecessary and invidious many of the clerical privileges which had been so essential in a simpler age. Thus, as European society developed, the clergy, the most cosmopolitan element of it, would necessarily lose some of the commanding influence they had exercised in the ages when they represented civilization as well as religion. But other causes were at work. The high religious enthusiasm of the earlier twelfth century was not maintained at the same level either in clergy or people. And indeed even that Christian age had had its dark side. Passion, the fierce passionate character of a primitive people, was not yet subdued. What had been won by the Hildebrandine movement had to be preserved. No moral victory is final: no generation can afford to disarm. The very success of the Church brought its dangers, and increased power tended to ambition and worldliness. The faults and the wealth of the clergy must have contributed something, it would be difficult to say how much, to the darkest feature of the age, the heresy which even in St. Bernard’s time lurked in secret nearly everywhere. This evil spread like a plague through Southern France and Italy, and kept appearing sporadically north of the Alps. It seemed to threaten Christian morals and Christian faith alike. So acute did the danger become in France that it almost justified the violences of the Albigensian Crusade; but the Church of the thirteenth century had nobler weapons than those of De Montfort or the Inquisition: the Friars and Scholastic movement attacked heresy, morally and intellectually, and routed it. Henceforth, however, till the sixteenth century, no great religious or monastic movement, common to Christendom, was provoked by the many moral and intellectual causes which led to the decline and fall of the medieval system and finally to the Reformation itself.

The history of the papacy cannot be separated from that of the Church. The great popes of the past had had a share which can hardly be over-estimated in binding together Christian society and raising its moral level; it is not surprising that the diminished influence of the papacy is among the causes of the disintegration of Christendom. It is difficult not to trace the decadence to the struggle with Frederick II. Before that struggle, in the days of Innocent III, the difficulties of the papacy were due to its agents, its subjects, to the very greatness of the task it had undertaken, not to the character or aims of the popes themselves, But from Gregory IX a different spirit seemed to prevail. The popes were engaged in a hand-to-hand conflict with a power which aimed at establishing a strong monarchy in Italy which threatened to stifle Roman and papal freedom; the contest was not being waged with an imperious but distant German: it was Italian, territorial and bitter. The spiritual ruler seemed almost merged in the sovereign of Rome and the feudal lord of Sicily. Money was necessary, and in order to obtain it funds had to be raised in other, and especially, transalpine lands, and by means which aroused much discontent and which affected the credit of Rome as the central court of Christendom. The conception of canon law, of a system of courts Christian and a sacred jurisdiction over-riding political frontiers, is a magnificent one, and the debt which European law owes to the canonists is admitted by the modern masters of legal history. It was a system, however, which had many rivals, and it required the support of a high moral prestige. Unfortunately, the machinery was, from the first, defective; there was no organization at Rome capable of dealing with the press of legal business, and even in the twelfth century complaints of venality and delay were frequent and bitter. Litigants are not easily satisfied, nor has the law often been at once impartial, cheap, and speedy in any country; yet it can hardly be denied that in the thirteenth century the Roman courts suffered from very serious abuses.

It is unnecessary to follow the fortunes of the papacy after the thirteenth century; the lesson of the French influence, of the schism, of the Italianization of the fifteenth-century popes, is but too clear. Though the essential rights of the Holy See were but seldom denied in those years, it was clear, when the crisis came, and when the papal supremacy had to bear the first attack, that that devotion which makes martyrs and the enthusiasm which inspires righteous rebellion were sadly lacking. It would seem, then, that the growth of national divisions, the increased secularism of everyday life, the diminished influence of the Church and the papacy, that all these interdependent influences had broken up the social unity of Christendom at least two centuries before the Reformation, yet it must never be forgotten that religious unity remained. As long as Christendom was Catholic it was a reality, a visible society with one head and one hierarchy. Though for the moment centrifugal tendencies were in the ascendant, the future was full of possibilities. A great religious movement, a revival of the Christian spirit, the reform which should have come when the Reformation came, any such appeal to the common faith and to Catholic loyalty might have brought the Christian nations together again, have put some check upon their internal absolutism and external combativeness, and have removed from the Christian name the reproach of mutual antagonism.

Such speculation is, however, as idle as it is fascinating; instead of the reform, of the renewal of the spiritual life of the Church round the old principles of Christian faith and unity, there came the Reformation, and Christian society was broken up beyond the hope of at least proximate reunion. But it was long before this fact was realized even by the Reformers, and indeed it must have been more difficult for a subject of Henry VIII to convince himself that the Latin Church was really being torn asunder than for us to conceive the full meaning and all the consequences of a united Christendom. Much of the weakness of ordinary men in the earlier years of the Reformation, much of their attitude towards the papacy, can be explained by their blindness to what was happening. They thought, no doubt, that all would come right in the end. So dangerous is it, particularly in times of revolution, to trust to anything but principle.

The effect of the Reformation was to separate from the Church all the Scandinavian, most of the Teutonic, and a few of the Latin-speaking populations of Europe; but the spirit of division once established worked further mischief, and the antagonism between Lutheran and Calvinist was almost as bitter as that between Catholic and Protestant. At the beginning, however, of the seventeenth century, Christendom was weary of religious war and persecution, and for a moment it almost seemed as if the breach were to be closed. The deaths of Philip II and Elizabeth, the conversion and tolerant policy of Henry IV of France, the accession of the House of Stuart to the English throne, the pacification between Spain and the Dutch, all these events pointed in the same direction. A like tendency is apparent in the theological speculation of the time: the learning and judgment of Hooker, the first beginnings of the High Church movement, the spread of Arminianism in Holland, these were all signs that in the Protestant Churches thought, study, and piety had begun to moderate the fires of controversy, while in the monumental works of Suarez and the other Spanish doctors, Catholic theology seemed to be resuming that stately, comprehensive view of its problems which is so impressive in the great Scholastics. It is not surprising that this moment, when the cause of reconciliation seemed in the ascendant, was marked by a scheme of Christian political union. Much importance was at one time attributed to the grand dessein of Henry IV. Recent historians are inclined to assign most of the design to Henry’s Protestant minister, Sully; the king’s share in the plan was probably but small. A coalition war against Austria was first to secure Europe against the domination of the Hapsburgs, but an era of peace was to follow. The different Christian States, whether Catholic or Protestant, were to preserve their independence, to practice toleration, to be united in a “Christian Republic” under the presidency of the pope, and to find an outlet for their energies in the recovery of the East. These dreams of Christian reunion soon melted away. Religious divisions were too deep-seated to permit the reconstruction of a Christian polity, and the cure for international ills has been sought in other directions. The international law of the seventeenth-century jurists was based upon national law, not upon Christian fellowship, the balance of power of the eighteenth century on the elementary instinct of self-defense, and the nationalism of the nineteenth on racial or linguistic distinctions. It has never occurred to anyone to take seriously the mystic terminology with which in the Holy Alliance Alexander I of Russia clothed his policy of conservative intervention. The Greek insurrection and the Eastern questions generally restored the word Christian to the vocabulary of the European chanceries, but it has come in recent times to express our common civilization rather than a religion which so many Europeans now no longer profess. (See Religions.)

FRANCIS URQUHART