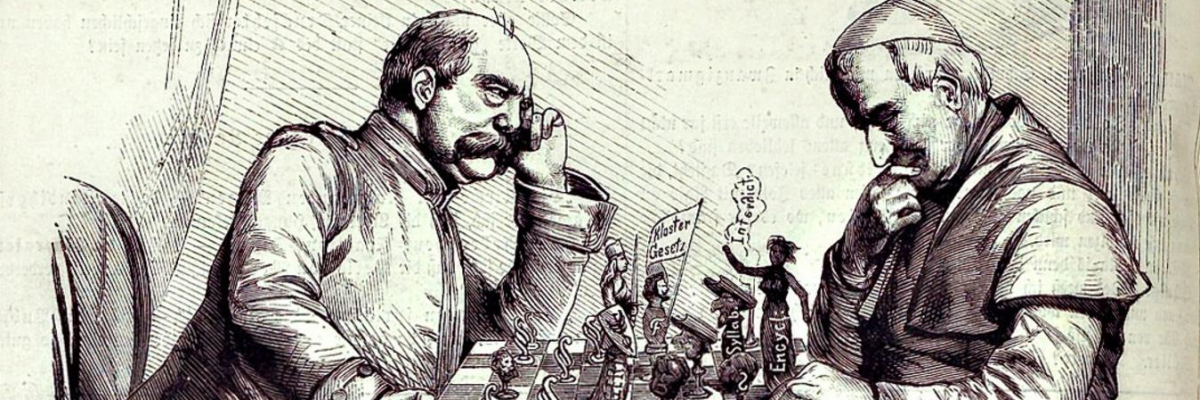

Kulturkampf, the name given to the political struggle for the rights and self-government of the Catholic Church, carried on chiefly in Prussia and afterwards in Baden, Hesse, and Bavaria. The contest was waged with great vigor from 1871 to 1877; from 1878 to 1891 it gradually calmed down. On one side stood the government, the Liberals, and the majority of the Conservatives; on the other, the bishops, the priests, and the bulk of the Catholic people. Prussia was the chief center of the conflict. The Prussian government and Prince Bismarck were the leaders in this memorable struggle.

CAUSES OF THE KULTURKAMPF, They are to be sought: (I) in the political party-life of Germany; (2) in the trend of ideas among the German people towards the middle of the nineteenth century; (3) in the general European policy of Bismarck after 1870.

(I) Moritz von Blankenburg was the leader of the Prussian Conservatives. From the first he declared himself openly and clearly in Parliament for an anti-Roman policy. The Conservatives represented the orthodox Protestants of Prussia, themselves threatened by the Liberal movement at that time opposed to all positive Christianity. Nevertheless the attitude of Blankenburg was no personal caprice. The Conservatives yet held in principle to the Protestant character of the State of Prussia as formerly constituted (i.e., up to the German Revolution of 1848). After the Constitution of 1848, it is true; this exclusively Protestant character of the State was no longer recognized by law. But the Conservatives jealously saw to it that as a matter of fact no change took place in Prussia. It could not be pleasing to them that the Catholics of the Rhineland and Westphalia should gradually rise to power through the new parliamentary institutions. When the German Empire was formed in 1870, and South Germany, in great majority Catholic, was thereby joined with Prussia, they conceived the gravest fears for the supremacy of Protestanism in Prussia.

However, the real instigators of the onslaught on German Catholicism were the German Liberals. Their attitude is thus explained: previous to 1860 the Liberal party had long been composed almost entirely of men belonging to narrow professional circles professors, lawyers, etc., also prominent business men. They united in opposition to political absolutism, and were eager for a larger constitutional life in Germany. But they had also an intellectual bond. Whether as anti-clerical disciples of French Deism or Austrian Josephinism, or as enthusiastic admirers of German poetry and philosophy (and therefore advocates of an undogmatic and unecclesiastical Christianity), they were all inimically disposed towards the Catholic Church and all positive belief. With the help of legislation and state schools they hoped to secure for “free and independent science’ (die freie Wissenschaft) an absolute control over the intellectual life of the whole German nation. Indeed, the original pioneers of the Liberal party were as unanimous in their philosophical views of the world and life as they were in their views of the State. In the beginning, therefore, they were inclined in their public utterances to promote equally both policies. Until 1860, however, they considered themselves too weak to undertake vigorous action in behalf of their Kultur aims, i.e., their intellectual and political ideals as described above. Isolated failures of an earlier date (the Kolner-Wirren, or ecclesiastico-political troubles of 1837, and the Deutsch-katholischen movement of Ronge in Baden, 1844-46) still served as warnings. In both cases vast masses of the people had been deeply troubled. Even the middle-class citizens, usually rather indifferent in matters of faith, were not yet ready to participate in religious conflicts of this nature. Their chief aims at that time were politico-economical; a little later, after 1850, the passion of national unity stirred deeply the entire Burgerthum of Germany. But when the Liberal influence increased after 1860 in the Prussian Parliament (Landtag) and in the various German states, the party leaders began to change their tactics. The Grand Duke of Baden confided to them the organization of the Ministerium, i.e., the civil administration of the State. Forthwith the Archbishop of Freiburg and the clergy of Baden were subjected to the strictest civil supervision. The Church was deprived of all free control of its property and revenues, with which, till then, the Government had not interfered. All ecclesiastical influence was expelled from the schools, and an effort made to introduce the spirit of “free science” even into the education of the clergy. It was a prelude of what was to take place throughout all Germany some ten years later. In the summer of 1860 Bavaria offered the Liberals a pretext for the introduction of their Kultur program. Of course, in so Catholic a people and state, no permanent results were attainable apart from a thorough transformation of popular life and thought. This was to be done by means of new educational laws and by the so-called Bavarian “social legislation”. The latter, in particular, was meant to clear the way for a complete renovation of the economic and social conditions of the Bavarian people. For the present, however, only preliminary steps were taken. Education was naturally the foremost question. Meantime the parliamentary supremacy of the Prussian Liberals, so recently and laboriously acquired and so essential for their success, was seriously challenged. In Otto von Bismarck, since the end of 1862 chief of the Prussian Ministry, they found a superior opponent. This led (1866-67) to the formation of a Prussian National Liberal Party committed to a reconciliation of the hitherto dominant Liberals with the now all-powerful minister. In this way it was hoped to secure again for the party its waning influence in Prussia. In public opinion the Liberals had been for three decades the chief representatives of the idea of national unity under Prussian headship. Bismarck had now realized that ideal, and in this fact was found the common ground between the National Liberals and the new master of German politics. Bismarck then abandoned his anti-Liberal attitude and for most of the next decade received the parliamentary support of the Liberals; towards the year 1870 the more important offices, both Prussian and German, were held by the Liberals. Soon the party began, in Prussia, as previously in Bavaria, to attack the Catholic ecclesiastical influence in the schools; politico-economical and social questions were also brought to the front apropos of the new and systematic legislation proposed. The National Liberals at this time reached the acme of popularity, owing to the universal enthusiasm over the defeat of France, also through the general satisfaction with the economic legislation of the party that left free scope to the growth of material interests.

The Kultur policy which the Liberal party then sought to impose on the newly-established empire and on its chief constituent states need not have produced the intense excitement that followed. It would have been possible, through the public press and assemblies, to keep up in the Parliament an appearance of peaceful legislative work and to influence in a moderate way the public opinion of the nation, somewhat, if we may so put it, as is now done in France. Instead of this, legislative action degenerated into a savage party struggle that aroused in the public mind all manner of violent emotions. The Liberal efforts to influence public opinion became so many fanatical assaults on the hereditary devotion to their Church of the orthodox Catholic masses. It is to be noted, however, that for this violence of temper there were certain reasons.

The great events of the years 1866-1871 had agitated deeply the now united German nation. It was not unnatural, therefore that its people should consider all political problems in the light of their extremest consequences, from the view-point of principles, and of the great ideas that were then appealing to the popular masses. In the average German mind at this period two great thoughts were dominant—the new-born German nationality and a new philosophy of man and life. Most German Catholics were very apprehensive for the future welfare of their religion in the ancient fatherland; as a matter of fact it was Protestant Prussia, the birthplace of Kant and the source of Hegelianism, that had accomplished the unity of Germany. Most Liberals, on the other hand, while they rejoiced over the settlement of the “German question” by Prussia, continued to hold the national unity as incomplete so long as the Germans were divided in religion and in the aforesaid fundamental philosophic views. They maintained that a permanent political unity of Germany depended absolutely on unity of religion, language, and education. On this ground they proclaimed the Catholic minority a foreign element in the new empire; it must be either assimilated or exterminated. The deep-rooted religious differences of Germany, thus brought again to the front in connection with the nation’s future, were freshly aroused, though such new occasion was scarcely necessary. Even while the Liberals yet hesitated to evoke them, they had, of themselves as it were, and by their own nature, taken on a new life.

As early as 1848, an important “Catholic Movement” sprang up in Germany. During the eighteenth century the German Catholics had been quite outmaneuvered by the Protestants, and in the early decades of the nineteenth century found themselves politically powerless. Economically they had fallen into the background, nor could they exercise socially an equal influence. In general education they were also backward, in comparison with their rivals. Their Catholic consciousness was therefore much weakened; no longer proud of their religion, they ceased to profess it openly and freely. But about the middle of the nineteenth century a change come over the Catholics of Germany, and they awoke to a fresh sense of the power and beauty of their religion. Simultaneously Catholic life took on a new development throughout the entire West, especially during the pontificate of Pius IX. This pope had a wonderful influence over the Catholic masses, whom he filled with a remarkable confidence and zeal, especially as to their public life. In the Syllabus of 1867 he condemned with great earnestness that Liberalism which was then everywhere proclaimed as the heir expectant of Catholicism. Thereupon, he convened an ecumenical council, the first in 300 years. At this turning-point the German Catholics, so long eliminated from the political, economic and educational life of their nation, rallied to the defense of their faith against Liberalism. Under papal leadership they devoted themselves to the defense of Christian teaching and life, violently attacked by a multitude of infidel writers, and undertook to with-stand the combined hosts of Protestantism and Liberalism. The Liberals, on the other hand, resented bitterly both Syllabus and Papal Infallibility; in some places ( Mannheim, Berlin) Catholics suffered from the violence of mobs. At the very time when the dogma of Papal Infallibility was being proclaimed, Germany was winning her great victories over France; to the Liberals (some of whom were thus minded in the Prussian war of 1866 against Austria) it seemed as if the time had come for the final conflict between the empire and papacy, the last decisive battle of the Reformation against enslavement of religious thought and subjection to ecclesiastical authority. Gradually and almost unconsciously, under the influence of the aforesaid political and ecclesiastical events, a situation that in the Liberal mind originally contemplated only a more or less comprehensive legislation, both as to the schools and the relations of Church and State, developed into one of the most passionate conflicts of principles ever fought out within the limits of a great nationality. This was the state of affairs when, in the fall of 1870, the Prussian Catholics, not satisfied with their widespread system of popular associations (Vereinswesen) undertook the creation of a new political party, the Center (Zentrum); on the other hand, in the Reichstag elections of the Spring of 1871 the, liberals overthrew the Conservatives and took up the reins of power. In April, 1871, the mutterings of the tempest were already heard in the opening debates of the Reichstag, especially in the debate on the Address to the Throne, when the Liberals insisted very pointedly on a flat and final rejection of any proposition looking towards the restoration of the Temporal Power, characterizing any such steps as an interference with the domestic affairs of a foreign people. As yet, however, no one had the courage to let loose the turbulent passions that filled men’s breasts, nor as late as the end of 1871 (Memoirs of Prince Hohenlohe) were the Liberal leaders ready to open the campaign. The Center remained on the defensive, occupied chiefly in outlining its parliamentary status. At this juncture Bismarck appeared on the scene.

He was then under strong nervous tension, owing to the extraordinary exertions and emotions of the “high stakes” policy of his previous eight years. He was dominated by the fear that new and more exhaustive wars would soon be necessary in order to defend the unity of Germany then barely won. In this temper he was deeply concerned lest within the empire itself the foreign enemy should find aid and succour from particularist or anti-Prussian elements, whose importance he easily over-estimated. At this stage of his diplomacy he was bent on preventing the recurrence of any situation similar to that of 1863-66, when he found himself helpless in the presence of a powerful parliamentary opposition. He was at all times naturally inclined to resent as unnecessary and therefore unjustifiable, any kind of parliamentary opposition. Quite indifferent to theories of home government and the division of political authority within the State, he was equally eager for a solid centralization and thorough reinforcement of all national resources, in view always of the foreign enemy. In this spirit he had once fought the Liberals, and compelled his former opponents to become the ardent supporters of his foreign policy. Now, on his return from France, he found before him a party, on the one hand more powerful in a parliamentary sense than the Liberal opposition of the sixties, while on the other it seemed to him gravely perilous in case of a foreign war. He was suspicious of one deputy, Ludwig Windthorst, in whom he at once recognized the real leader of the Center.

While Bismarck was fully aware of the high abilities of Windthorst, he knew also that he was a former subject of the House of Hanover and was still in close touch with that dynasty, that he had never approved the exclusion of Austria from the German unity as accomplished by Bismarck, and that he vigorously disapproved the excessive favor shown by Bismarck to the Liberals, both in Prussian and in imperial affairs. He had already suffered a notable defeat at Windthorst’s hands in the Tariff Parliament of 1868, on which occasion Bismarck tried in vain to obtain from the assembly anything more than the politico-economical services for which it had been called (i.e. he failed then to secure the peaceful union of the South German States with the North German Confederation). Windthorst at that time had no strong parliamentary following, yet his political strategy had proved successful. But now a strong party was at his back, and, as its acknowledged leader, he lost no occasion to increase its influence. On the one hand he appealed to certain Conservatives, superior to Protestant prejudices, and unalterably opposed to the National Liberals as enemies of Christianity and the traditional German views of the State; on the other he was always ready to combine with those Liberals who had not yet gone over unconditionally to Bismarck. This welcoming of recalcitrant Liberals was always Bismarck’s chief cause of complaint. He had also persuaded himself from the beginning that the Center entertained foreign relations inimical to the new German Empire. After the Franco-Prussian War the chancellor seems to have feared a conflict with Russia as champion of the new Panslavism. He had in large measure the habitual distrust of Prussia for its Polish subjects, and was persuaded that in case of war they would be on the side of Panslavism—that, whether in war or diplomacy, they would always prove a thorn in the side of Germany. He had watched them closely for several years and noted with deep suspicion the alliance of their deputies with the German Catholics. He laid great stress on this fact; as is well known, the Polish question is one of those which cause most uneasiness to Prussian statesmen. It offended him, moreover, that Catholic members of the Center frequented the Radziwill salons in Berlin, and were thereby willing to appear friendly to Polish demands and aspirations.

His suspicions were still further aroused by the undeniably lively zeal which the Catholic clergy at large exhibited for the growth of the Center, while, under Wind horst’s direction, the party was standing out not only for the rights of the Catholic Church, but also for a definite political program. This zeal of the German clergy was at this juncture especially odious to Bismarck; despite his clear-headed political realism, his imagination was deeply affected by the idea that Protestant Prussia had restored to Germany its former imperial grandeur precisely when Papal Infallibility was being proclaimed at Rome. In his eyes the empire once more stood over against the papacy; only there was now added another antithesis, that of Protestant individual freedom against submission to ecclesiastical authority. He persuaded himself that Rome was less friendly to the new empire than any other European power, and that it meant to unite against the new Protestant Empire all the Catholic nations of Europe and its own priesthood everywhere. To obtain definite information as to the relations of Rome and the Center he demanded, in the spring of 1871, through the Bavarian ambassador at the Vatican, that Rome should censure the Center party for its antagonistic attitude in the Parliament. A friendly answer was made him by the Holy See, but on the representation of prominent members of the Center, notably of Bishop Ketteler, Rome refused to further influence the Catholic party, whereat the indignation of the chancellor was boundless. In the meantime the South German Liberals, foremost among them Prince Hohenlohe stirred up unceasingly his original mistrust of the Center, the Catholic clergy, and Rome.

Though for a while slow to act, he became daily more convinced that a grave peril for the empire existed in the activity of a powerful parliamentary party of German Catholics under the leadership of a man like Windthorst, to which must be added the influence of the Vatican over this party. In his eyes the Center was an outcome of the German Catholic Movement (die katholische Bewegung); deprived of the support of the latter it would collapse. Now the Catholic Movement, as he knew it since 1850, was for Bismarck something entirely hostile; it had been friendly to Austria, and its adherents were numerous in Southern Germany and Westphalia. Moreover, its enthusiasm for Rome and for the independence of the Catholic Church was odious to him. As a Prussian official he believed in a State Church; the Church should not only be under the supervision of the State, but should positively serve the purposes of the State. It seemed, therefore, that the psychological moment had come for the arrest of this Catholic Movement. All Germany was enthusiastic over the new-born imperial unity. To judge by various occurrences within the ranks of German Catholicism, it seemed as if Rome had gone too far in its claims on the obedience of German Catholics in matters of faith. The Old-Catholic organization then taking shape seemed a likely nucleus for a German National Church, a State Church for Catholics; it would welcome all seceders from Rome and guarantee them a new ecclesiastical life. Old-Catholicism, he argued, must be supported; the Roman Catholic clergy forced to submit; the masses behind the Catholic Movement must be intimidated; the immediate pressure of Roman authority removed from them, and the Center stigmatized before its constituents as an enemy of the German Empire.

COURSE OF THE CONFLICT. It may be divided roughly into three periods: 1871-72; 1872-78;1878-91.

1871-72.—The aforementioned views of Bismarck concerning the Center and the Catholic Movement were by no means so clearly worked out in the summer of 1871 that he was then ready to begin a systematic onslaught on German Catholicism. For a year and a half his policy was manifested only in individual cases, though in all such cases a unity of attitude was clearly exhibited. As early as July 8, 1871, he abolished the Catholic Section of the Prussian Ministry of Worship and gave over henceforth to officials in great majority Protestant the conduct of all governmental matters pertaining to Catholic churches and schools. His excuse was that the members of the aforesaid Catholic Section of the Department of Worship were guilty of too close relations with the Poles. Towards the end of 1871 he proceeded, on similar grounds, against the Catholic clergy of the eastern provinces of Prussia; he introduced at that time in the Reichstag a law concerning the supervision of instruction and education. This act contemplates the extension of the civil school-supervision to religious instruction and simultaneously the abolition of all ecclesiastical supervision of the entire primary-school system hitherto exercised conjointly with the civil authorities. Henceforth, whenever the schools of a district were entrusted to ecclesiastical superintendents, their authority was to be derived solely from the State; in large measure, moreover, the Catholic clergy were excluded from any supervision of the schools.

During the discussion of this School Supervision Law, Bismarck made an extremely violent attack (February 2, 1872) on Windthorst’s leadership of the Center, held out to the latter the olive branch of peace on condition of abandoning Windthorst, but threatened, in case of refusal, to pillory the party before all Germany as an enemy of the Empire. Shortly afterwards he caused the house of a Polish canon in Posen to be searched by the police, in the hope of finding there correspondence that would enable him to convict Windthorst of an alliance with the Poles. In this he was unsuccessful. On July 4, 1872, the Reichstag passed the law against the Jesuits (Jesuitengesetz), on the plea that they were the emissaries of Rome in Germany (pretending at the same time to free the bishops from the Jesuit yoke); moreover, in defiance of all legality (both from a Conservative and a Liberal standpoint) the Jesuits were handed over to the arbitrary supervision of the police authorities and could at any moment be expelled from the Empire. In addition, the Bundesrath (Imperial Supreme Council) interpreted the law to mean complete exclusion from all ministry either in church or school. Thereupon the Jesuits left Germany. The next year the law was extended to the Redemptorists, Lazarists, Fathers of the Holy Ghost, and the Ladies of the Sacred Heart, as being closely related to the Jesuits, whereupon these orders also left Germany. In the same month the Government again manifested its ecclesiastico-political views by the measures which it sanctioned against the Prussian bishops, in the interest of the Old Catholics. Still earlier (December 1, 1871) the so called Kanzelparagraf, or “pulpit-law”, was, for a similar purpose, incorporated in the Criminal Code. The Bishop of Ermland had forbidden the Old Catholic teacher of religion (Religionslehrer) in Braunsburg Gymnasium any longer to exercise his office. The Government then interfered and compelled the parents to send their children to the lessons of this instructor. Later, after a unanimous protest from the bishops of Prussia, the Government abandoned its position in this case, but demanded from the Bishop of Ermland a declaration to the effect that “in the future he would obey in their entirety the laws of the State”. He refused to make the declaration, whereupon his salary was withheld. A similar treatment befell the Catholic Head Chaplain (Feldpropst) of the Prussian Army, to whom pertained the administration of public worship for the Catholic soldiers. At Cologne the church of the Catholic military chaplain had been turned over by the Government to the Old Catholics, whereupon the Head-Chaplain of the troops forbade his subordinate to hold there the usual Catholic services. The Cologne chaplain was then brought before the Minister of War and suspended as guilty of “resisting the administrative ordinances of his superiors”.

The close relation of Bismarck s anti-Catholic attitude in Germany with his foreign policy was soon shown in his famous papal election dispatch (May 14, 1872), in which he invited the European governments to agree on the conditions under which they would recognize the next papal election. The dispatch was ineffective, equally so Bismarck’s attempt to compel the pope to accept, as the German Empire’s first ambassador to the Vatican, Cardinal Hohenlohe, brother of the above-mentioned Prince Chlodwig Hohenlohe whose close relations to both National Liberals and Old Catholics were well-known. On this occasion Bismarck uttered the celebrated words: “Nach Canossa gehen wir nicht” (We shall not go to Canossa), i.e., he foretold the real issue of the conflict before it had yet fairly begun. Nevertheless he was now fully determined to carry it on to the end. He found a ready instrument in the person of Herr Falk, appointed Minister of Worship in January, 1872, a clever and personally well-meaning man, but a jurist of a very formalist type and an extreme partisan. The chancellor had already, February 7, 1872, urged the Minister of the Interior to undertake the solution of the Polish question “on a basis of principle, actively, and aggressively”; he now engaged Falk to walk in the same course. He was “to make known with all due clearness and in every sense the relations of the State to the various religious societies”. On the side of the Church her defenders began now to seek the open. The Prussian hierarchy, assembled at Fulda for its annual meeting, issued (September 20, 1872) a memorial to all the German States in which the recent anti-ecclesiastical measures were treated in their entirety, exhibited for the judgment of public opinion, and proof supplied that rights of the Church hitherto acknowledged both by international and national law had been seriously violated. Pius IX, moreover, lifted his voice twice in protest. On the first occasion (June 24, 1872) he said to the German Catholics in Rome that Bismarck had placed himself at the head of the persecutors of the Church. “Who knows, however, but that soon the little stone will fall from the mountain and strike the feet of the colossus and shatter it?” Another time (Christmas Consistory, 1872) he spoke reprovingly of “men who not only do not belong to our holy religion, but do not even know it, yet arrogate to themselves authority to decide concerning the doctrines and the rights of the Catholic Church“. The popular agitation grew from day to day. The Association of German Catholics (Mainzer Verein), founded under the presidency of Baron Felix von Loe, soon counted 200,-000 members, and took a much bolder attitude than the Center, whose leader, Windthorst, observed at all times much moderation.

In the meantime Falk aimed to make the Catholic bishops independent of Rome, the clergy independent of the bishops, and both dependent on the State. The following means were in his mind destined to accomplish these aims. The education of the clergy was to depend entirely, or nearly so, on the State, and to be carried out in the spirit of the average German Liberalistic education. Next, all ecclesiastical offices were to be filled only after approval by the highest civil authority in each province. In the future all ecclesiastical courts outside Germany should no longer exercise any disciplinary power over the Prussian clergy. From all German ecclesiastical courts there was to lie, in the future, an appeal not only on the part of the accused, but also of the Chief President (on grounds of public interest), to a court composed of civil officials and to be known as the “Royal Court of Justice for Ecclesiastical Affairs”. Falk sought also to restrict considerably the exercise of the Church‘s punitive and disciplinary authority, in other words to facilitate apostasy so that priests and laymen who chose to side with the State might suffer no inconvenience. It was evident from these measures that Falk had no idea of the close and indivisible solidarity of German Catholicism whereby bishop and clergy on one side, and the bishop and Rome on the other, were intimately bound to one another. He erred most grievously, however, when he made it a criminal offense for any priest to exercise his ministry without due authorization from the civil power, and “silenced” every bishop who refused to comply with the new legislation. In case the German clergy remained loyal to the Church these measures meant the withdrawal of the sacraments from the Catholic people, i.e., the most grievous spiritual suffering. The plans of Falk were formulated in four bills. The first was laid before the Land tag in November, 1872, the other three in January, 1873, though the royal consent was obtained with difficulty and only after insistence on the severity of the aforesaid papal allocution at Christmas of 1872. It was during the discussion of these Falk Bills that the word Kulturkampf was first used. The Land tag (Prussian Assembly) Commission to which the Falk Bills were referred expressed grave doubts as to their constitutionality, seeing that the Prussian Constitution guaranteed to the Catholic Church an independent administration of her own affairs. The Commission did not, therefore, advise the rejection of the Falk Bills, but rather proposed an amendment to the Constitution to the effect that in all her administration the Church was subject to the laws of the State and the juridically authorized supervision of the same.

B. 1872-78.—This amendment and the four bills were adopted in May, 1873, hence the term May Laws (Maigesetze). To hasten their execution the Prussian Ministry at once enabled the Old Catholics to establish themselves as a Church, and contributed large sums for that purpose. It also encouraged the public adhesion of so-called State Catholics, i.e. Roman Catholics who protested formally their willingness to obey the new laws. Nevertheless, both Old Catholies and State Catholics remained few in number. On the other hand the unexpected happened in the shape of a remarkable development of ecclesiastical loyalty on the part of the Catholics. The bishops of Prussia had protested beforehand (January 30, 1873) against the forthcoming legislation. On May 2 they issued a common pastoral letter in which they made known to the faithful the reasons why all must offer to these laws a passive but unanimous resistance. On May 26 they declared to the Prussian Ministry that they would not cooperate for the execution of the Falk Laws. Almost without exception the clergy obeyed the mandate of the bishops. Thereupon the punishments prescribed by the laws for their violation were at once applicable; in hundreds of cases fines were soon imposed on the clergy for the execution of their ecclesiastical ministry. As none of the condemned ecclesiastics would voluntarily pay the imposed fines, these were forcibly collected, to the great irritation and embitterment of the Catholic parishioners. Soon the prisons began to open, and Falk declared (October 24, 1873) that still greater severity would be used. The Minister of War declared Catholic theological students subject to military service; the Marian congregations were forbidden to exist; the Catholic popular associations and the political activity of the Center (public meetings, Catholic press) was subjected to close and inimical supervision, in every way hindered, and the Catholic population persecuted for their fidelity to the party. In December, 1873, changes were made in the oath of loyalty taken by the bishops to the king, every reference to their oath to the pope was stricken out, and an unconditional observance of the laws of the State prescribed. These measures, however, did not produce the desired results. In the November elections (1873) the Center returned to the Landtag 90 members instead of its former 50, and to the Reichstag 91 instead of its former 63. The number of its votes was doubled, and reached about 1,500,000. The number of Catholic papers increased in 1873 to about 120.

Falk sought to overcome all this Catholic opposition by fresh ravages on the pastoral ministry. New laws of the Landtag (May, 1874) supplemented his authority and put at his disposal new means of compulsion. It was provided that when a bishop was deposed a representative agreeable to the Government should be appointed; if none such were to be had, appointments to vacant parishes should lie in the hands of the “patrons” in each parish, or should take place by free election of the parishioners. The Reichstag aided by passing a Priests-Expulsion Law (Priesterausweisungsgesetz) by which all priests deprived of their offices for violation of the May Laws were turned over to the discretion of the police authorities. During the debates on this law the Archbishops of Posen and Cologne and the Bishop of Trier were condemned to imprisonment; later, the Archbishop of Posen (Count Ledochowski) was deposed. Shortly after the promulgation of the new May Laws the Ministry saw to it that all the Prussian sees were vacated. A very great number of parishes were also deprived of their pastors. The ecclesiastical educational institutions were closed. These renewed efforts were no more successful than the former measures. No cathedral chapter chose an administrator, and no parish elected a parish priest. The exiled bishops governed their sees from abroad through secretly delegated priests. The faithful everywhere made it possible to hold Divine Service. The pope declared, February 5, 1875, the May Laws invalid (irritas). On all sides exasperation was well-nigh boundless.

Under these circumstances Bismarck himself took charge of the situation. His main hope still lay in proving that the Center party was the enemy of the empire, and this stigma he endeavored by all possible means to fasten upon it; could he do so, the party would be isolated in the Reichstag, and soon helpless. At Kissingen, July 13, 1874, the Catholic cooper’s apprentice, Kullmann attempted to assassinate him. Though the chancellor had no evidence to justify his assertion, he declared in a public session of the Reichstag that the murderer “held to the coattails of the Center”, and refused to consider any denial of the charge by that party. Bismarck now called to his aid two allies which in the past he had always found serviceable in face of great popular opposition, i.e. hunger and penury. The methods of Bismarck differed considerably from those of Falk. The latter saw in the religious life of the Catholic people their chief fortress, and so attacked it with all earnestness, hoping to meet with victory in the tumultuary reaction likely to follow any interference with the spiritual needs of an entire people. In this there was for Bismarck too much idealism; he chose rather to appeal to the material needs of his opponents. On April 22, 1875, he obtained from the Landtag the so-called Sperrgesetz, by which all state payments to the Catholic bishops were withheld until they or their representatives complied with the new laws. Another law of the Landtag (May 31, 1875) closed all monasteries in Prussia, and expelled from Prussian territory all members of religious orders, with the exception of those who cared for the sick—and they were variously restricted. Finally (June 20, 1875), he dealt the Catholic Church what seemed to him a crushing blow; on that date was passed in the Landtag a law which confiscated all the property of the Church, and turned over its administration to lay trustees to be elected by the members of each parish. To accomplish this he had previously to commit another act of supreme violence, i.e. the abolition of those paragraphs of the Prussian Constitution which concerned the Church. The aforesaid Kanzelparagraf, or “pulpit-law”, was now amended by the Reichstag (February 26, 1876) so as to enable the Government to prosecute before the criminal courts any priest who should criticise in the pulpit the laws or the administration of the Prussian State. In the following years sixteen million marks ($3,250,000) were withheld by the Government from the Church, by virtue of the Sperrgesetz; two hundred and ninety-six monastic institutions were closed. By the end of 1880, 1125 parish priests and 645 assistants had fallen victims to the new laws (out of 4627 and 3812, respectively). Within the circle of their operation 646,000 souls were entirely deprived of spiritual assistance. We must add to this the Falk Ordinance of February 18, 1876, issued with Bismarck’s consent, by which in the future religious instruction in the primary schools was to be given only by teachers appointed or accepted by the State, i.e., all Catholic ecclesiastical control was suppressed.

The debates on all these measures were the most violent ever heard in the German Parliament; it was apparent that on both sides the leadership would soon fall to the extremists. On the Catholic side, therefore, evidences of moderation were soon forthcoming, and tended to prevent further extreme measures on the part of the Government. The bishops felt that the gravest perils had been successfully met and averted. The earliest relief was the result of legislation originally intended to do great damage to the Catholic cause. The Prussian Civil Marriage Law of March, 1874 (extended to the German Empire, February 6, 1875), withdrew from the clergy their former right of keeping the civil registers, and made civil marriage obligatory. It was hoped that in this way the laity at least would be freed from ecclesiastical control, since neither bishops nor clergy were willing to separate from Rome. Under the circumstances, however, the law turned to the advantage of the sorely persecuted Church. Had marriages remained possible only in the presence of civilly recognized priests, the Catholic population, in the end, given the absolute necessity of marriages, would have had to accept one of two issues: either they would tolerate the state clergy, or they would bring pressure to bear on the Catholic clergy in the sense of obedience to the new laws. On the other hand the bishops met successfully Bismarck’s secularization of the Church property. They declared that in this respect it was material interests which were chiefly at stake, and in such cases the Church was always inclined to the most conciliatory measures; confiding therefore, in the ecclesiastical loyalty of the faithful they directed them to obey these laws. In the mean-time by the laws of June 7, 1876, and February 13, 1878, Bismarck undertook to sequestrate all Church property; he had already failed, however, in his original purpose. Windthorst, on the other hand, strove earnestly to check all extremist tendencies among the Catholics and to incline them to peace with the Government as soon as the ecclesiastical situation would permit. In this temper a reconciliation was evidently no longer remote, much less impossible. It was now clear to Bismarck that the popular agitation had reached a height that no material force could overcome, and that the civil authority itself was endangered. The chief motive that had originally led him to enter on this grave conflict with German Catliolicism had long since disappeared; since 1875 he no longer feared an anti-German coalition of Catholic powers or a war with Russia. In the meantime those closer relations with Austria had begun which in 1879 terminated in the actual Triple Alliance. His new foreign policy brought with it a frequent rapprochement with the Catholics. In the German Parliament he could no longer act quite independently of them, and this was another factor in the future reconciliation. The National Liberals in the Reichstag had ceased to be his unconditional supporters in the grave questions of internal reform (politico-economical, social, and financial) that now claimed all his attention. The continued opposition of so large a party as the Center was henceforth an element of grave danger for all his plans. Conservative Protestants, meanwhile, rebelled against the Liberalism of Falk, which under the circumstances was far more offensive to them than to Catholics. Moreover, Emperor Wilhelm inclined daily more in their direction. Indeed, the position of Falk had become practically untenable:

1878-91.—The death of Pius IX and the election of Leo XIII (February, 1878) made possible the restoration of peace in the much troubled Fatherland. At once, and again during that year, Leo XIII wrote in a conciliating way to Kaiser Wilhelm urging the abolition of the May Laws. His request was refused; at the same time Berlin expressed a desire for reconciliation. In July, 1878, Bismarck had a personal interview with the papal nuncio, Masella, at Kissingen (in Bavaria). However, a full decade was yet to intervene before the May Laws quite disappeared. The proposed basis of negotiations was not calculated at this juncture to bring about the much desired peace. Bismarck insisted that the May Laws should not be abolished by any formal act; he was willing, however, to modify their application, obtain gradually from the Landtag temporary discretionary authority in regard to the laws, remove certain odious points, etc., all this on condition of a yielding attitude on the side of the Catholics. The latter, indeed, were in this respect praiseworthy. Bismarck further desired that in all measures of relief the Government should appear to take the initiative—of course after proper diplomatic negotiations with Rome. In return he demanded from the Curia an assurance that the Center party would support the policies of the Government; otherwise the latter could have no interest in a reconciliation.

As a proof of goodwill he dismissed Herr Falk in 1879 and replaced the author of the odious May Laws by Herr Puttkamer, whose ecclesiastico-political attitude was more conciliatory than that of his predecessor. Under him the Church began to regain its former influence over the schools. He obtained from the Landtag on three occasions (1880-83) discretionary authority to modify the May Laws; thereby he provided for a restoration of orderly diocesan administration, and the filling of the vacant sees. The vacant parishes, it is true, remained yet without pastors; it was allowed however, to administer them from neighboring parishes. After 1883 the Sperrgesetz, or suspension of ecclesiastical salaries, was not enforced. In 1882 Prussia established an embassy at the Vatican. Bismarck in the meantime held firmly to one point: the obligation of the bishop to make known to the Government all ecclesiastical appointments, and the Government’s right of veto. This much Rome was not disinclined to allow, but demanded a previous formal abolition of at least certain portions of the May Laws. Leo XIII was very anxious to reestablish peace and harmony with Germany and for that reason chose for his secretary of state, in 1881, Lodovico Jacobini, who had been nuncio at Vienna since 1879, and had conducted the preliminary negotiations. During the negotiations that followed, the principal defect of the papal diplomacy consisted in the excessive stress it laid on the purely politico-ecclesiastical elements of the problem (those which affected the general European situation of the Church), not sufficiently taking into account the fundamental source of the conflict, i.e., the violation of the constitutional law of Prussia. From this point of view it did not seek to cooperate with the tactics of the Center in that party’s dealings with Bismarck; it rather complied in several ways with the wishes of the latter, and sought to influence the Center (in substantially political matters) in favor of the Government. On the other hand, while Windthorst did not perhaps give quite sufficient consideration to the general European situation, he was all the more earnest in his resolution to give permanency to the exertions of his party, to again anchor the rights of the Church in the Prussian Constitution, and to make the latter document guarantee once again the independence of a the Church. During these years of more or less fruitful negotiations between Rome and Berlin, the political power of the Center in the Reichstag grew notably; the Government was no longer able to count on a majority against it. By this time the Conservatives had again obtained the upper hand in the Landtag, and soon made evident their intention to abolish completely the Falk system of interference with the disciplinary and pastoral life of the Catholie Church (Conservative Resolution, April 25, 1882). When Bismarck saw that it was impossible to make the Center a government party (spring of 1884), the negotiations on his side were temporarily dropped. To the Conservatives, now urgent, he replied that he was ready to proceed to a revision of the May Laws as soon as he knew that Rome would accept the Anzeigepflicht, or obligation of making known to the Government all ecclesiastical appointments, with the corresponding civil right of veto. He believed, apparently, that the Kulturkampf agitation would gradually die out, and the Catholic people grow weary of their struggle for “a constitutional and legal independence of the Church“, now that the most burden-some of the May Laws had been withdrawn and a somewhat orderly ecclesiastical life was again possible.

In the meantime the Center party and its press kept alive a strong Catholic feeling. On the other hand, the foreign situation soon brought up the question of the final abolition of the May Laws. Bismarck was again anxious in regard to Russia, and this time feared an alliance of that nation with France; the recent awakening of Panslavism added to his solicitude on this point. He was concerned lest the Vatican should favor the Franco-Russian alliance. On the other hand he now sought to rally all forces at the disposal of the Government for the suppression of the Polish movement that had by this time taken on large proportions; owing to his Kulturkampf policy, all classes of the Polish people had been deeply stirred during the previous decade, and their attitude now caused the chancellor great anxiety. He hoped, also, that a decisive ending of the ecclesiastical conflict would seriously affect the hitherto intact solidarity of the Center and weaken notably the popular attachment to the party, whereby its influence, even yet the source of his gravest political difficulties, would finally diminish. Leo XIII saw clearly that Bismarck was now earnestly desirous of peace; Rome, therefore, it seemed, need no longer be over timid in the matter of concessions based on suitable guarantees. The pope also hoped that Bismarck would in turn be helpful to him in respect of the German imperial policy towards Italy. It was of considerable importance that at this juncture the most statesmanlike member of the Prussian hierarchy, Bishop Kopp of Hildesheim (now Cardinal, and Prince-Bishop of Breslau), was made a member of the Prussian House of Lords (Herrenhaus). Bismarck still held with tenacity to the former government claims. In the matter of the Anzeigepflicht, the nominations of parish priests at least should not take place without the Government’s approval. Nor would he listen to the restoration of the former recognition of the Church by the Prussian Constitution. Finally, he held in its entirety to the state control of the schools. In reality he was able to maintain these three points; on the other hand he yielded to the Church, practically, the control of ecclesiastical education, permitted the reassertion of the papal disciplinary authority over the clergy, allowed the restoration of public worship and the administration of the sacraments, the application of ecclesiastical disciplinary measures (censures, etc.), and held out to the religious orders the hope of returning. This is substantially the content of the two comprehensive laws (May 21, 1886, and April 29, 1887), that modified the May Laws in an acceptable way and thereby ended formally the long conflict since known as the Kulturkampf.

During the negotiations for the first law the pope had allowed the bishops (April 25, 1886) to lay before the Government for approval the appointments of parish priests. While the second law was under discussion the pope declared that it showed the way to peace, while Bismarck termed it the restoration of a modus vivendi between State and Church. The Center was deeply suspicious of both laws because the pope did not insist on constitutional guarantees. In the interval between these laws, and in view of them, the chancellor made a last attempt to obtain through Rome the support of the Center for his military policy and the foreign aims it implied. He wished the Center to vote in the Reichstag for the so-called Septennate. A correspondence ensued between Cardinal Jacobini and the President of the Center Party; Windthorst was not to be moved from his position. It may be said that the hopes of Leo XIII in Bismarck’s help respecting Italy were deceived. In the following years the last remnants of the May Laws disappeared. The law prescribing the expulsion of all priests (Priesterausweisungsgesetz) was withdrawn in 1890, and in 1891 the Sperrgelder (i.e. the ecclesiastical salaries, etc., withheld since April, 1875) were distributed to the various German dioceses. For a while it seemed as if another grave conflict would follow, this time apropos of the schools. However, since the early nineties there has prevailed the present quiescent attitude in all matters ecclesiastical and educational. It may be added that the anti-Jesuit legislation was so modified in 1905 as to offer no longer its former exceptional character; the Redemptorists had been previously allowed to return. One important consequence of the Kulturkampf was the earnest endeavor of the Catholics to obtain a greater influence in national and municipal affairs; how weak they formerly were in both respects was clear to them only after the great conflict had begun. These efforts took the name of the Paritatsbewegung, i.e., a struggle for equality of civil recognition. In turn the discussions awakened and fed by this movement soon led to a vigorous self-questioning among the Catholic masses as to the fact of, and the reasons for, their backwardness in academic, literary, and artistic life, also in the large field of economic activities (industry, commerce, etc.). On the other hand the reconciliation between Church and State made it possible for the Catholics of Germany to participate more earnestly than hitherto in the public life of the Fatherland, in illustration of which we may point to the notable contributions of the Center Party (1896-1904) to the solution of the great imperial problems of that period. At present (1908) a reaction seems imminent. In closing it may be said that the Kulturkampf rightly appears as only the first phase of the vast movement of antagonism in which Catholicism stands over against Protestantism and Liberalism, on the broad field of Prussia, henceforth one of the great powers of Europe, and within the German nation now coalescent in the political unity of the Empire.

MARTIN SPAHN