Hospitals (Lat. hospes, a guest; hence hospitalis, hospitable; hospitium, a guest-house or guest-room). Originally, hospital meant a place where strangers or visitors were received; in the course of time, its use was restricted to institutions for the care of the sick. This modification is incidental to the long development through which the hospital itself has passed under the varying influences of religious, political, and economic conditions, and of social and scientific progress. Viewed in a large way the typical modern hospital represents natural human solicitude for suffering, ennobled by Christian charity and made efficient by the abundant resources of medical skill.

PAGAN ANTIQUITY., While among savage tribes, e.g. the ancient Germans, the sick and feeble were often put to death, more humane practices are found among civilized peoples. One of the earliest hospitals on record was founded in Ireland! 300 B.C., by Princess Macha. It was called “Broils Bearg” (house of sorrow), and was used by the Red Branch Knights and served as the royal residence in Ulster until its destruction in A.D. 332 (“Seanchus Mbr”, 123; cf. Sir W. Wilde, “Notes on Ancient Ireland“, pt. III). In India, the Buddhist King Azoka (252 B.C.) established a hospital for men and animals. The Mexicans in pre-Columbian times had various institutions in which the sick and poor were cared for (Bancroft, “Native Races”, II, 596). In a general way the advance in medical knowledge implies that more was done to relieve suffering; but it does not necessarily prove the existence of hospitals. From the Papyri (notably Ebers) we learn that the Egyptians employed a considerable number of remedies and that the physicians held clinics in the temples. Similar customs prevailed in Greece; the sick resorted to the temple of. Esculapius where they spent the night (incubatio) in the hope of receiving directions from the god through dreams which the priests interpreted. Lay physicians (Aesculapiades) conducted dispensaries in which the poor received treatment. At Epidaurus the Roman senator Antoninus erected (A.D. 170) two establishments, one for the dying and the other for women lying-in; patients of these classes were not admitted in the Aesculapium.

The Romans in their treatment of the sick adopted many Greek usages. Al sculapius had a temple on the island in the Tiber (291 B.C.), where now stand the church and monastery of St. Bartholomew, in which the same rites were observed as among the Greeks. Municipal physicians were appointed to treat various classes of citizens, and these practitioners usually enjoyed special privileges and immunities. Provision was made in particular for the care of sick soldiers and slaves, the latter receiving attention in the valetudinaria attached to the estates of the wealthier Romans. But there is no record of any institution corresponding to our modern hospital. It is noteworthy that among pagan peoples the care of the sick bears no proportion to the advance of civilization. Though Greece and Rome attained the highest degree of culture, their treatment of the sick was scarcely equal, certainly not superior, to that which was found in the oriental nations. Both Greeks and Romans regarded disease as a curse inflicted by supernatural powers and rather sought to propitiate the malevolent deity than to organize the work of relief. On the other hand the virtue of hospitality was quite generally insisted on; and this trait, as will presently appear, holds a prominent place in Christian charity.

EARLY CHRISTIAN TIMER—Christ Himself gave His followers the example of caring for the sick by the numerous miracles He wrought to heal various forms of disease including the most loathsome, leprosy. He also charged His Apostles in explicit terms to heal the sick (Luke, x, 9) and promised to those who should believe in Him that they would have power over disease (Mark, xvi, 18). Among the “many wonders and signs done by the Apostles in Jerusalem” was the restoration of the lame man (Acts, iii, 2-8), of the palsied Aeneas (ix, 33, 34), and of the cripple at Lystra (xiv, 7, 9), besides the larger number whom the shadow of St. Peter delivered from their infirmities (v, 15, 16). St. Paul enumerates among the Charismata (q.v.) the “grace of healing” (I Cor—xii, 9), and St. James (v, 14, 15) admonishes the faithful in case of sickness to bring in the priests of the Church and let them pray over the sick man “and the prayer of faith shall save him.” The Sacrament of Extreme Unction was instituted not only for the spiritual benefit of the sick but also for the restoration of their bodily health. Like the other works of Christian charity, the care of the sick was from the beginning a sacred duty for each of the faithful, but it devolved in a special way upon the bishops, presbyters, and deacons. The same ministrations that brought relief to the poor naturally included provision for the sick who were visited in their homes. This was especially the case during the epidemics that raged in different parts of the Roman Empire, such as that at Carthage in 252 (St. Cyprian, “De mortalitate”, XIV, in Migne, P.L—IV, 591-593; “S. Cypriani Vita” in “Acta SS.”, September 14), and that at Alexandria in 268 (Eusebius, “Hist. Eccl.”, VII, xxii; “Acta SS.”, VI, 726). Valuable assistance was also rendered by physicians, slaves, or freedmen, who had become Christians and who like Cosmas and Damian were no less solicitous for the souls than for the physical needs and bodily comfort and wellbeing of their patients.

Another characteristic of Christian charity was the obligation and practice of hospitality (Rom—xii, 13; Heb—xiii, 2; I Peter, iv, 9; III Ep. St. John). The bishop in particular must be “given to hospitality” (I Tim—iii, 2). The Christian, therefore, in going from place to place, was welcomed in the houses of the brethren; but like hospitality was extended to the pagan visitor as well. Clement of Rome praises the Corinthians for their hospitality (Ep. ad. Cor—c. i) and Dionysius of Corinth for the same reason gives credit to the Romans (Eusebius, “Hist. Eccl.”, iv, 23). The bishop’s house above all others was open to the traveler who not only found food and shelter there but was provided in case of need with the means to continue his journey. In some cases the bishop was also a physician so that medical attention was provided for those of his guests who needed it (Harnack, “Medicinisches aus d. altesten Kirchengesch.” in “Texte u. Untersuchungen” VIII, Leipzig, 1892). The sick were also cared for in the valetudinaria of the wealthier Christians who in the spirit of charity extended hospitality to those who could not be accommodated in the bishop’s house. There was thus from the earliest times a well organized system of providing for the various forms of suffering; but it was necessarily limited and dependent on private endeavor so long as the Christians were under the ban of a hostile State. Until persecution ceased, an institution of a public character such as our modern hospital was out of the question. It is certain that after the conversion of Constantine, the Christians profited by their larger liberty to provide for the sick by means of hospitals. But various motives and causes have been assigned to explain the development from private care of the sick to the institutional work of the hospital (Uhlhorn, I, 317 sq.). It was not, at any rate, due to a slackening of charity as has been asserted (Moreau-Christophe, “Du probleme de la misere”, II, 236; III, 527), but rather to the rapid increase in the number of Christians and to the spread of poverty under new economic conditions. To meet these demands, a different kind of organization was required, and this, in conformity with the prevalent tendency to give all work for the common weal an institutional character, led to the organization and founding of hospitals.a

When and where the first hospital was established is a matter of dispute. According to some authorities (e.g. Ratzinger, p. 141), St. Zoticus built one at Constantinople during the reign of Constantine, but this has been denied (cf. Uhlhorn, I, 319). But that the Christians in the East had founded hospitals before Julian the Apostate came to the throne (361) is evident from the letter which that emperor sent to Arsacius, high-priest of Galatia, directing him to establish a xenodochium in each city to be supported out of the public revenues (Soxomen, V, 16). As he plainly declares, his motive was to rival the philanthropic work of the Christians who cared for the pagans as well as for their own. A splendid instance of this comprehensive charity is found in the work of St. Ephraem who, during the plague at Edessa (375), provided 300 beds for the sufferers. But the most famous foundation was that of St. Basil at Caesarea in Cappadocia (369). This “Basilias”, as it was called, took on the dimensions of a city with its regular streets, buildings for different classes of patients, dwellings for physicians and nurses, work-shops and industrial schools. St. Gregory of Nazianzus was deeply impressed by the extent and efficiency of this institution which he calls “an easy ascent to heaven” and which he describes enthusiastically (Or. 39, “In laudem Basilii”; Or. fun. “In Basil.”, P. G—XXXVI, 578-579). St. Basil’s example was followed throughout the East: at Alexandria by St. John the Almsgiver (610); at Ephesus by the bishop, Brassianus; at Constantinople by St. John Chrysostom and others, notably St. Pulcheria, sister of Theodosius II, who founded “multa publica hospitum et pauperum domicilia” i.e. many homes for strangers and for the poor (Acta SS—XLIII). In the same city, St. Samson early in the sixth century, founded a hospital near the church of St. Sophia (Procopius, “De aedif. Justiniani”, I, c. 2); this was destroyed but was restored under Justinian who also built other hospitals in Constantinople. Du Cange (Historia Byzantina, II, “Constantinopolis Christiana”) enumerates 35 establishments of the kind in this city alone. Among the later foundations in Constantinople, the most notable were the orphanotrophium established by Alexius I (1081-1118), and the hospital of the Forty Martyrs by Isaac II (1185-1195).

The fact that the first hospitals were founded in the East accounts for the use, even in the West, of names derived from the Greek to designate the main purpose of each institution. Of the terms most frequently met with the Nosocomium was for the sick; the Brephotrophium for foundlings; the Orphanotrophium for orphans; the Ptochium for the poor who were unable to work; the Gerontochium for the aged; the Xenodochium for poor or infirm pilgrims. The same institution often ministered to various needs; the strict differentiation implied by these names was brought about gradually. In the West, the earliest foundation was that of Fabiola at Rome about 400. “She first of all”, says St. Jerome, “established a nosocomium to gather in the sick from the streets and to nurse the wretched sufferers wasted with poverty and disease” (Ep. LXXVII, “Ad Oceanum, de morte Fabiol”, P.L—XXII, 694). About the same time, the Roman senator Pammachius founded a xenodochium at Porto which St. Jerome praises in his letter on the death of Paulina, wife of Pammachius (Ep. LXVI, P.L—XXII, 645). According to De Rossi, the foundations of this structure were unearthed by Prince Torlonia (“Bull. di Arch. Christ.”, 1866, pp. 50, 99). Pope Symmachus (498-514) built hospitals in connection with the churches of St. Peter, St. Paul, and St. Lawrence (Lib. Pontif. I, no. 53, p. 263. During the pontificate of Vigilius (537-555) Belisarius founded a xenodochium in the Via Lata at Rome (Lib. Pontif, 1. c. 296). Pelagius II (578-590) converted his dwelling into a refuge for the poor and aged. Stephen II (752-757) restored four ancient xenodochia, and added three others. It was not only in countries that retained the traditions of pagan culture and civilization that Christianity exerted its beneficent influence; the same spirit of charity appears wherever the Christian Faith is spread among the fierce and uncultured peoples just emerging from barbarism.

The first establishment in France dates from the sixth century, when the pious King Childebert and his spouse founded a xenodochium at Lyons, which was approved by the Fifth Council of Orleans (549). Other foundations were those of Brunehaut, wife of King Sigibert, at Autun (close of sixth century); of St. Radegonda, wife of Clotaire, at Athis, near Paris; of Dagobert I (622-638), at Paris; of Caesarius and his sister St. Caesaria at Arles (542); and the hospice to which Hincmar of Reims (806-882) as-signed considerable revenues. Regarding the origin of the institution later known as the Hotel-Dieu, at Paris, there is no little divergence of opinion. It has been attributed to Landry, Bishop of Paris; Haser (IV, 28) places it in 660, De Gerando (IV, 248) in 800. According to Lallemand (II, 184) it is first mentioned in 829 (cf. Coyecque, “L’Hotel-Dieu de Paris au Moyen Age”, I, 20). As the name indicates, it belongs to that group of institutions which grew up in connection with the cathedral or with the principal church of each large city and for which no precise date can be assigned. The same uncertainty prevails in regard to other foundations such as the hospitalia Scothorum, established on the Continent by Irish monks, which had fallen into decay and which the Council of Meaux (845) ordered to be restored. In Spain the most important institution for the care of the sick was that founded in 580 by Bishop Masona at Augusta Emerita (Merida), a town in the Province of Badajoz. From the account given by Paul the Deacon we learn that the bishop endowed this hospital with large revenues, supplied it with physicians and nurses, and gave orders that wherever they found a sick man, “slave or free, Christian or Jew”, they should bring him in their arms to the hospital and provide him with bed and proper nourishment (cibos delicatos eosque praeparatos). See Florez, “Espana Sagrada”, XIII, 539; Heusinger, “Ein Beitrag”, etc. in “Janus”, 1846, I.

MIDDLE AGES.—During the period of decline and corruption which culminated under Charles Martel the hospitals, like other ecclesiastical institutions, suffered considerably. Charlemagne, therefore, along with his other reforms, made wise provision for the care of the sick by decreeing that those hospitals which had been well conducted and had fallen into decay should be restored in accordance with the needs of the time (Capit. duplex, 803, c. iii). He further ordered that a hospital should be attached to each cathedral and monastery. Hincmar in his “Capitula ad presbyteros” (Harduin, V, 392) exhorts his clergy to supply the needs of the sick and the poor. Notwithstanding these measures, there followed, after Charle-magne’s death (814), another period of decadence marked by widespread abuse and disorder. The hospitals suffered in various ways, especially through the loss of their revenues which were confiscated or diverted to other purposes. In a letter to Louis the Pious written about 822, Victor, Bishop of Chur, complains that the hospitals were destroyed. But even under these unfavorable conditions many of the bishops were distinguished by their zeal and charity, among them Ansgar (q.v.), Archbishop of Hamburg (d. 865), who founded a hospital in Bremen which he visited daily. During the tenth century the monasteries became a dominant factor in hospital work. The famous Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, set the example which was widely imitated throughout France and Germany. Besides its infirmary for the religious, each monastery had a hospital (hospitale pauperum, or eleemos, varia) in which externs were cared for. These were in charge of the eleemosynarius, whose duties, carefully prescribed by the rule, included every sort of service that the visitor or patient could require. As he was also obliged to seek out the sick and needy in the neighborhood, each monastery became a center for the relief of suffering. Among the monasteries notable in this respect were those of the Benedictines at Corbie in Picardy, Hirschau, Braunweiler, Deutz, Ilsenburg, Liesborn, Pram, and Fulda; those of the Cistercians at Arnsberg, Baumgarten, Eberbach, Himmenrode, Herrnalb, Volkenrode, and Walkenried. No less efficient was the work done by the diocesan clergy in accordance with the disciplinary enactments of the councils of Aachen (817, 836), which prescribed that a hospital should be maintained in connection with each collegiate church. The canons were obliged to contribute towards the support of the hospital, and one of their number had charge of the inmates. As these hospitals were located in cities, more numerous demands were made upon them than upon those attached to the monasteries. In this movement the bishop naturally took the lead, hence the hospitals founded by Heribert (d. 1021) in Cologne, Godard (d. 1038) in Hildesheim, Conrad (d. 975) in Constance, and Ulrich (d. 973) in Augsburg. But similar provision was made by the other churches; thus at Trier the hospitals of St. Maximin, St. Matthew, St. Simeon, and St. James took their names from the churches to which they were attached. During the period 1207-1577 no less than one hundred and fifty-five hospitals were founded in Germany (Virchow in “Gesch. Abhandl.”, II).

The Hospital Orders.—The establishment of confraternities and religious orders for the purpose of ministering to the sick is one of the most important phases in this whole development. The first of these appeared at Siena towards the end of the ninth century, when Soror (d. 898) founded the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala and drew up its rules. The management was largely in the hands of the citizens, though subject to the bishop’s control until 1194, when Celestine III exempted it from episcopal jurisdiction. Similar institutions, for the most part governed by the Rule of St. Augustine, sprang up in all parts of Italy; but by the beginning of the thirteenth century they had passed from the bishop’s control to that of the magistrate. In the northern countries—Belgium, France, and Germany—the Beguines and Beghards (q.v.), established in the latter part of the twelfth century, included in their charitable work the care of the sick. St. Elizabeth of Hungary founded two hospitals at Eisenach and a third on the Wartburg. The origin and work of the Alexians and Antonines have been described in the articles Alexians and Orders of Saint Anthony. sub-title Antonines. But the most important of the orders established during this period was that of the Holy Ghost. About the middle of the twelfth century (c. 1145) Guy of Montpellier had opened in that city a hospital in honor of the Holy Ghost and prescribed the Rule of St. Augustine for the brothers in charge. Approved April 23, 1198, by Innocent III, this institute spread rapidly throughout France. In 1204 the same pontiff built a hospital called S. Maria in Sassia, where King Ina, about 728, had founded the schola for English pilgrims. By the pope’s command, Guy de Montpellier came to Rome and took charge of this hospital, which was thenceforward called Santo Spirito in Sassia. (Cf. Morichini, “Instituti di carita. in Roma”, Rome, 1870.) The pope’s example was imitated all over Europe. Nearly every city had a hospital of the Holy Ghost, though not all the institutions bearing this name belonged to the order which Guy of Montpellier had founded. In Rome itself Cardinal Giovanni Colonna founded (1216) the hospital of S. Andrea, not far from the Lateran; and in accordance with the will of Cardinal Pietro Colonna the hospital of S. Giacomo in Augusta was founded in 1339. Querini (“La Beneficenza Romana”, Rome, 1892) gives the foundations in Rome as follows: eleventh century, four; twelfth, six; thirteenth, ten; fourteenth, five; fifteenth, five, i.e. a total of thirty hospitals for the care of the sick and infirm founded in the city of the popes during the Middle Ages.

The Military Orders.—The Crusades (q.v.) gave rise to various orders of chivalry which combined with military service the care of the sick. The earliest of these was the Order of St. John. Several hospitals had already been founded in Jerusalem to provide for pilgrims; the oldest was that connected with the Benedictine Abbey of S. Maria Latina, founded according to one account by Charlemagne in 800; whether the Order of St. John grew out of this or out of the hospital established (1065-70) by Maurus, a wealthy merchant from Amalfi, is uncertain. At all events, when the First Crusade reached Jerusalem in 1099, Gerhard the superior of the latter hospital, gave the establishment a new building near the church of St. John the Baptist, whence apparently the order took its name. It also spread rapidly in the Holy Land and in Europe, especially in the Mediterranean ports which were crowded with crusaders. Its original purpose was hospital work and according to the description given (c. 1160) by John of Wisburg (Pez, “Anecdota”, I, 3, 526) the hospital at Jerusalem cared for over 2000 patients. The military feature was introduced towards the middle of the twelfth century. In both respects the order for a time rendered excellent service, but during the thirteenth century increasing wealth and laxity of morals brought about a decline in Christian charity and zeal and the care of the sick was in large measure abandoned.

The Teutonic Order developed out of the field hospital under the walls of Acre, in which Count Adolf of Holstein with other German citizens (from Bremen and Lubeck) ministered to the sick and wounded. Under the name of “domus hospitalis S. Mariae Teutonicorum in Jerusalem“, it was approved by Clement III in 1191. The members bound themselves by vow to the service of the sick, and the rule prescribed that wherever the order was introduced it should build a hospital. The center of its activity, however, was soon transferred from the Holy Land to Europe, especially to Germany where, owing to its strict organization and excellent administrative methods, it was given charge of many already existing hospitals. Among its numerous establishments those at Elbmg and Nuremberg enjoyed the highest repute. In spite, however, of prudent management and of loyalty to its original purpose, the Teutonic Order suffered so severely through financial losses and war that by the end of the fifteenth century its pristine vigor was almost spent.

City Hospitals.—The Crusades, by opening up freer communication with the East, had quickened the spirit of commercial enterprise throughout Europe, and in consequence, the city, as distinct from the feudal estate and the village, came into existence. The resulting economic conditions affected the hospital development in two ways. The increasing population of the cities necessitated the construction of numerous hospitals; on the other hand, more abundant means were provided for charitable work. Foundations by the laity became more frequent. Public-spirited individuals, guilds, brotherhoods, and municipalities gave freely towards establishing and endowing hospitals. In this movement the Italian cities were foremost. Monza in the twelfth century had three; Milan eleven; Florence (fourteenth century) thirty. The most famous were: La Casa Santa di Santa Maria Annunziata at Naples, founded in 1304 by the brothers Niccolo and Giacomo Scondito; Santa Maria Nuova at Florence (1285) by Falco Portinari, the father of Dante’s Beatrice; and the Ospedale Maggiore at Milan (1456) by Duke Francesco Sforza and his wife Bianca Maria. The German towns were no less active; Stendal had seven hospitals; Quedlinburg, four; Halberstadt, eight; Magdeburg, five; Halle, four; Erfurt, nine; Cologne, sixteen (cf. Uhlhorn, II, 199 sq.).

As to the share which the municipalities took in this movement, opinions differ. Some authors (Uhlhorn, Ratzinger) hold that in most cases the city hospital was founded and endowed by the city authorities; while others (Lallemand, II, 51) declare that between the twelfth and the sixteenth centuries, comparatively few foundations were made by the municipality, though this often seconded private initiative with lands and subventions and willingly took over the direction of hospitals once they were established. It is however beyond question that the control of the hospitals passed quite generally into the hands of the municipality especially in Italy and Germany. As a rule the transfer was easily effected on the basis of an agreement between the superior and the civil authorities, e.g. Lindau, 1307; Lucerne, 1319; Frankfort, 1283; Cologne, 1321. In certain cases where dispute arose as to the observance of the agreement, the matter was referred to high ecclesiastical authority. Thus the Holy Ghost hospital at Gottingen was given over to the municipality by order of the Council of Basle in 1470 (Uhlhorn, loc. cit.). Such transfers, it should be noted, implied no opposition to ecclesiastical authority; they simply resulted from the general development which obliged the authorities in each city to intervene in the management of institutions on which the public weal in large measure depended. There was no question of secularization in the modern sense of the term. Much less can it be shown that the Church forbade clerics any share in the control of hospitals, though some modern writers have thus interpreted the decree of the Council of Vienne in 1311. In reply to Frere Orban (pseud—Jean Vaudamme, “La mainmorte et la charity”, Brussels, 1857), Lallemand points out (II, 106 sq.) that what the council did prohibit was the conferring of hospitals and their administration upon clerics as benefices (“nullus ex locis ipsis saecularibus clericis in beneficium conferatur”). The decree was aimed at an abuse which diverted hospital funds from their original charitable purpose to the emolument of individuals. On the other hand, the Council of Ravenna in the same year (1311), considering the waste and malversation of hospital revenues, ordered that the management, supervision, and control of these institutions should be given exclusively to religious persons.

In France, the movement in favor of secular control advanced much more slowly. King Philip Augustus in 1200 decreed that all hospitals and hospital funds should be administered by the bishop or some other ecclesiastic. The Council of Paris (1212) took measures to reduce the number of attendants in the hospitals which, the bishops declared, were meant for the service of the sick and not for the benefit of those in good health. At the Council of Arles (1260) it was enacted, in view of prevalent abuses, that hospitals should be placed under ecclesiastical jurisdiction and conducted by persons who would “lead a community life, present annual reports of their administration and retain for themselves nothing beyond food and clothing” (can. 13). Similar decrees were issued by the Council of Avignon (1336). But the protests of synods and bishops were of little avail against growing disorders. Even the Hotel-Dieu at Paris, which in the main had been well managed, began in the fifteenth century, to suffer from grave abuses. After various attempts at reform, the chapter of Notre-Dame requested the municipal authorities to take over the administration of the hospital (April, 1505). Accordingly a board composed of eight persons, delegates of the municipality, was appointed and, with the approval of the court, assumed charge of the Hotel-Dieu (Lallemand, II, 112).

Great Britain and Ireland.—In these countries the care of the sick, like other works of charity, was for a long time entrusted to the monastic orders. Each monastery, taking its pattern from those on the Continent, provided for the treatment both of its own inmates who fell ill and of infirm persons in the neighborhood. In the Penitential of Theodore (668-690) we read (VI, 15): “in potestate et libertate est monasterii susceptio infirmorum in monasterium”, i.e. the monastery is free to receive the sick. According to Harduin (IV, 864) a large hospital was founded at St. Albans in 794. A little later (796) Alcuin writing to Eanbald II, Archbishop of York, exhorts him to have in mind the foundation of hospitals where the poor and the pilgrims may find admission and relief (Haddan and Stubbs, “Councils“, Oxford, 1871, III, 504). The temporal rulers also were generous in this respect. In 936 King Athelstan returning from his successful campaign against the Scots, made certain grants to the Culdees or secular canons of St. Peter’s Cathedral, York, which they employed to found a hospital. This was known at first as St. Peter’s, afterwards as St. Leonard’s from the name of the church built in the hospital by King Stephen. It provided for 206 bedesmen and was served by a master, thirteen brethren, four seculars, eight sisters, thirty choristers, and six servites. Archbishop Lanfranc in 1084 founded the hospital of St. Gregory outside the north gate of Canterbury and endowed it with lands and other revenues. It was a large house, built of stone and divided into two sections, one for men and the other for women.

During the first quarter of the twelfth century (1123 ?), St. Bartholomew‘s hospital was founded by Rahere, who had been jester of Henry I, but had joined a religious community and secured from the king a grant of land in Smoothfield near London. This continued to be the most prominent hospital of London until its confiscation by Henry VIII. The Holy Cross hospital at Winchester was founded in 1132 by Henry of Blois, half-brother to King Stephen; St. Mary’s Spital, in 1197 by Walter Brune, citizen of London, and his wife Roesia. The latter, at the Dissolution, had 180 beds for sick persons and travellers. In 1215 Peter, Bishop of Winchester, established St. Thomas’s hospital in London. This also was confiscated by Henry VIII but was reestablished by Edward VI. At the present time St. Bartholomew‘s and St. Thomas’s are among the most important hospitals in London. The list of foundations in England is a long one; Tanner in his “Notitiae” men-tions 460, For their charters and other documents see Dugdale, “Monasticon Anglicanum”, new ed—London, 1846, VI, pt. 2. That these institutions were under episcopal jurisdiction is clear from the enactment of the Council of Durham (1217): “those who desire to found a hospital must receive from us its rules and regulations” (Wilkins, I, 583). Nevertheless, abuses crept in, so that in the “Articles on Reform” sent by Oxford University to Henry V in 1414, complaint is made that the poor and sick are cast out of the hospitals and left unprovided for, while the masters and overseers appropriate to themselves the revenues (Wilkins, III, 365).

In Scotland, 77 hospitals were founded before the Reformation; Glasgow had two, Aberdeen four, Edinburgh five. St. Mary Magdalen‘s at Roxburgh was founded by King David I (1124-1153); Holy Trinity at Soltre by King Malcolm IV (1153-1163); the one at Rothean by John Bisset about 1226; Hollywood in Galloway by Robert Bruce’s brother Edward (d. 1318); St. Mary Magdalen‘s at Linlithgow by James I (1424-1437). To the three existing hospitals at Aberdeen, Bishop Gavin Dunbar (1518-1532) added a fourth. The foundations at Edinburgh have already been mentioned under Edinburgh (vol. V—286). “The form of the hospital was generally similar to that of the church; the nave formed the common room, the beds were placed in the transepts, and the whole was screened off from the eastern end of the building, where was the chapel.. The hospitals were usually in charge of a warder or master, assisted by nurses. There was a chaplain on the staff, and the inmates were bound to pray daily for their founders and benefactors.” (Bellesheim, “History of the Catholic Church in Scotland“, Edinburgh, 1887, II, 185, 417; cf. Walcot, “The Ancient Church of Scotland“, London, 1874).

The existence of numerous hospitals in Ireland is attested by the names of towns such as Hospital, Spital, Spiddal, etc. The hospital was known as forus tuaithe i.e. the house of the territory, to indicate that it cared for the sick in a given district. The Brehon Laws (q.v.) provide that the hospital shall be free from debt, shall have four doors, and there must be a stream of water running through the middle of the floor (Laws, I, 131). Dogs and fools and female scolds must be kept away from the patient lest he be worried (ibid.). Whoever unjustly inflicted bodily injury on another had to pay for his maintenance either in a hospital or in a private house. In case the wounded person went to a hospital, his mother, if living and available, was to go with him (ibid—III, 357; IV, 303, 333; see also Joyce, “A Social History of Ancient Ireland“, London, 1903, I, 616 sq.). In the later development, the Knights of St. John had a number of hospitals, the most important of which was Kilmainham Priory founded about 1174 by Richard Strongbow. Other commanderies were located at Killhill, at Hospital near Emly in Co. Lime-rick, at Kilsaran in Co. Louth, and at Wexford. Towards the end of the twelfth century, the establishments of the Crutched Friars or Crossbearers, were to be found in various parts of Ireland; at Kells was the hospital of St. John Baptist founded (1189-1199) by Walter de Lacie, Lord of Meath; at Ardee, the one founded in 1207 by Roger de Pippard, Lord of Ardee, the charter of which was confirmed by Eugene, Archbishop of Armagh; at Dundalk, the priory established by Bertrand de Verdon, which afterwards became a hospital for both sexes. The hospital of St. John Baptist at Nenagh, Co. Tipperary, known as “Teach Eoin” was founded in 1200 by Theobald Walter, First Butler of Ireland. St. Mary’s hospital at Drogheda, Co. Louth, owed its origin (thirteenth century) to Ursus de Swemele, Eugene, Archbishop of Armagh, being a witness to the charter. The hospital of St. Nicholas at Cashel with fourteen beds and three chaplains was founded by Sir David Latimer, Seneschal to Marian, Archbishop of Cashel (1224-1238). In 1272 the hospital was joined to the Cistercian Abbey in the neighborhood. In or near Dublin ample provision was made for the care of the sick. About 1220, Henry Loundres, Archbishop of Dublin, founded a hospital in honor of God and St. James in a place called the Steyne, near the city of Dublin, and endowed it with lands and revenues. The Priory of St. John Baptist was situated in St. Thomas Street, without the west gate of the city. About the end of the twelfth century, Ailred de Palmer founded a hospital here for the sick. In 1361, it appearing that the hospital supported 115 sick poor, King Edward III granted it the deodanda for twenty years. This grant was renewed in 1378 and in 1403. About 1500, Walter, Archbishop of Dublin, granted a void space of ground to build thereon a stone house for ten poor men. On June 8, 1504, John Allen, then dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, founded the said hospital for sick poor, to be chosen principally out of the families of Allen, Barret, Begge, Hill, Dillon, and Rodier, in the Dioceses of Meath and Dublin; and to be faithful Catholics, of good fame, and honest conversation; he assigned lands for their support and maintenance, and further endowed the hospital with a messuage in the town of Duleek, in the County of Meath (Archdall, “Monasticon Hibernicum”, London, 1786). At the Reformation all these funds and charities became the property of the Protestant Church of Ireland.

The famines and pestilences which scourged these countries during the Middle Ages called into existence a considerable number of institutions, in particular the leper-houses. This name, however, was often given to hospitals which cared for ordinary patients as well as for those stricken with the plague. What was originally opened as a leper-house and, as a rule, endowed for that purpose, naturally became, as the epidemic subsided, a general hospital. There were some leper-hospitals in Ireland, but it is not easy to distinguish them in every case from general hospitals for the sick poor. Thus the hospital built by the monks of Inmsfallen in 869 is merely called nosocomium although it is usually reckoned an early foundation for lepers in Ireland. A hospital at Waterford was “confirmed to the poor” by the Benedictines in 1185. St. Stephen’s in Dublin (1344) is specially named as the residence of the “poor lepers of the city”, in a deed gift of about 1360-70; a locality of the city called Leper-hill was perhaps the site of another refuge. Lepers also may have been the occupants of the hospitals at Kilbixy in Westmeath (St. Bridget’s), of St. Mary Magdalene’s at Wexford (previous to 1408), of the house at “Hospital”, Lismore (1467), at Downpatrick, at Kilclief in County Down, at Cloyne, and of one or more of four old hospitals in or near Cork. The hospital at Galway built “for the poor of the town” about 1543, was not a leper-house, nor is there reason to take the old hospital at Dungarran as a foundation specially for lepers” (Creighton, “A History of Epidemics in Britain”, Cambridge, 1891, p. 100).

Action of the Papacy.—Innumerable pontifical documents attest the interest and zeal of the popes in behalf of hospitals. The Holy See extends its favor and protection to the charitable undertakings of the faithful in order to ensure their success and to shield them against molestation from any source. It grants the hospital permission to have a chapel, a chaplain, and a cemetery of its own; exempts the hospital from episcopal jurisdiction, making it immediately subject to the Holy See; approves statutes, intervenes to correct abuses, defends the hospital’s property rights, and compels the restitution of its holdings where these have been unjustly alienated or seized. In particular, the popes are liberal in granting indulgences, e.g. tothe founders and patrons, to those who pray in the hospital chapel or cemetery, to all who contribute when an appeal is made for the support of the hospital, and to all who lend their services in nursing the sick (Lallemand, op. cit—III, 92 sq.; Uhlhorn, op. cit—II, 224).

Character of the Medieval Hospitals.—It is not possible to give any account in detail that would accurately describe each and all these institutions; they differed too widely in size, equipment, and administration. The one common feature was the endeavor to do the best possible for the sick under given circumstances; this naturally brought about improvement, now in one respect now in another, as time went on. Certain fundamental requisites, however, were kept in view throughout the Middle Ages. Care was taken in many instances to secure a good location, the bank of a river being preferred: the Hotel-Dieu at Paris was on the Seine, Santo Spirito at Rome, on the Tiber, St. Francis at Prague, on the Moldau, the hospitals at Mainz and Constance, on the Rhine, that at Ratisbon, on the Danube. In some cases, as at Fossanova and Beaune, a watercourse passed beneath the building. Many of the hospitals, particularly the smaller ones, were located in the central portion of the city or town within easy reach of the poorer classes. Others again, like Santa Maria Nuova in Florence and a good number of the English hospitals, were built outside the city walls for the express purpose of providing better air for the inmates and of preventing the spread of infectious and contagious diseases of all kinds.

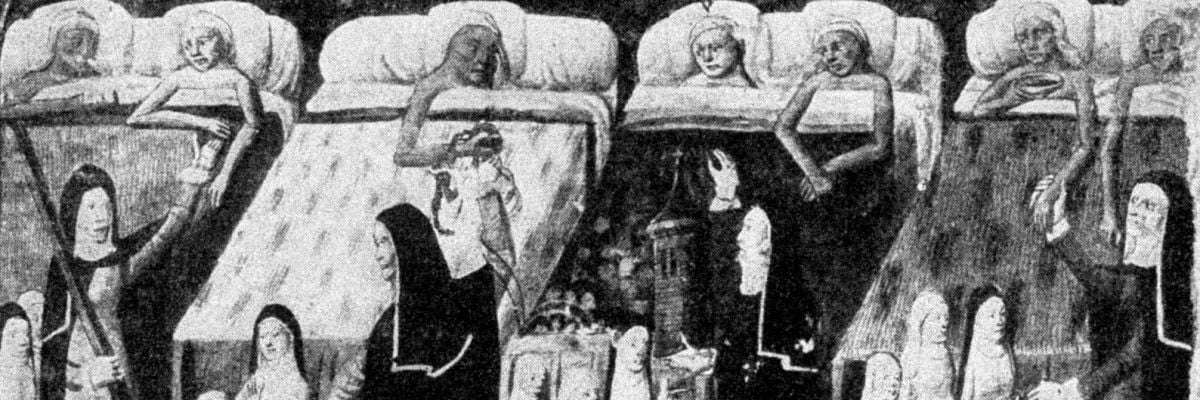

As regards construction, it should be noted that many of the hospitals accommodated but a small number of patients (seven, fifteen, or twenty-five), the limit being usually determined by the founder or benefactor: in such cases a private dwelling sufficed or at most a building of modest dimensions. But where ampler endowment was provided the hospital was planned by able architects and constructed on a larger scale. The main ward at Santo Spirito, Rome, was 409 ft. in length by 40 ft. in width; at Tonnerre, 260 ft. by 60; at Angers, 195 ft. by 72; at Ghent, 180 ft. by 52; at Frankfort, 130 ft. by 40; at Chartres, 117 ft. by 42. In hospitals of this type, an abundant supply of light and air was furnished by large windows, the upper parts of which were immovable while the lower could be opened or closed. To these, in some cases (Santo Spirito, Rome), was added a cupola which rose from the middle of the ceiling and was supported by graceful columns. The interior was decorated with niches, paintings, and armorial bearings; in fact the same artistic skill that so richly adorned the churches was employed to beautify the hospital wards. The hospital at Siena “constitutes almost as striking a bit of architecture as any edifice of the period and contains a magnificent set of frescoes, some of them of the fourteenth century, many others of later centuries” (Gardner, “Story of Siena“, London, 1902). The hospital founded (1293) at Tonnerre in France by Margaret of Burgundy, a sister-in-law of St. Louis, combined many advantages. It was situated between the branches of a small stream, and its main ward, with arched ceiling of wood, was lighted by large pointed windows high up in the walls. At the level of the window sills, some twelve feet from the floor, a narrow gallery ran along the wall from which the ventilation might be regulated and on which convalescent patients might walk or be seated in the sun. The beds were separated by low partitions which secured privacy but could be moved aside so as to allow the patients to attend Mass said at an altar at the end of the ward. This arrangement of a chapel in connection with the principal ward was adopted in many establishments; but the alcove system was not so frequently met with, the beds being placed, as a rule, in several rows in the one large open hall.

Hospital construction reached a high degree of perfection about the middle of the fifteenth century. Probably the best example of it is the famous hospital at Milan, opened in 1445, though not completed until the close of the fifteenth century. Dr. W. Gill Wylie in his Boylston Prize Essay on Hospitals says of it: “In 1456 the Grand Hospital of Milan was opened. This remarkable building is still in use as a hospital and contains usually more than 2000 patients. The buildings stand around square yards, the principal one being much larger than the others, and separating the hospital into two parts. The main wards on either side of this large court form a cross, in the center of which was a cupola, with an altar beneath it, where divine service is performed daily in sight of the patients. These wards have corridors on both sides which are not so lofty as the ceilings of the wards, and consequently there is plenty of room for windows above these passages. The ceilings are thirty or forty feet high, and the floors covered with red bricks or flags. The outside wards are nothing but spacious corridors. The wards are first warmed by open charcoal brasiers…. This Hospital built at the time when the Church of Rome was at the height of her power, and but a short time before the Reformation, is a good example of what had been attained toward the development of hospitals and it shows how much a part of the Church the institution of hospitals was.”

The administration of the hospital when this formed part of a monastery, was naturally in the hands of the abbot or prior and the details were prescribed in the monastic rule. The statutes also of the hospital orders (knights) regulated minutely the duties of the “Commander”, who was at the head of each hospital. In other institutions, the official in charge was known as magister, provisor, or rector, this last title being given in Germany to the superior in case he was a priest, while in Italy he was called spedalingo. These officials were appointed by the bishop, the chapter, or the municipality, sometimes by the founder or patron. Laymen as well as clerics were eligible; in fact, legacies were sometimes made to a hospital on condition that only lay directors should have control, as, for instance, in the case of St. Matthew’s at Pavia.

The regulations most generally adopted were those of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem; the Rule of St. Augustine and that of the Dominicans were also observed in many institutions. The first duty of the rector or magister was to take an inventory of the hospital holdings and appurtenances; he was obliged to begin this within a month after his appointment and to finish it within a year. Besides the general superintendence of the hospital, he was responsible for the accounts and for the whole financial administration, including the properties of the hospital itself and the deposits of money which are often entrusted to him for safekeeping. It was also his duty to receive each patient and assign him to his proper place in the hospital.

The brothers and sisters were bound by the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience which they took at the hands of a priest, or, as at Coventry (England), at the hands of the prior and chapter. As in all religious establishments, the schedule of duties was strictly prescribed, as were also the details of dress, food, and recreation. No one employed in the hospital was allowed to go out unaccompanied, to spend the night, or take any refreshment other than water outside the hospital. Penalties were inflicted for violation of these rules.

In the reception of patients, the broadest possible charity was shown. As Coyecque (op. cit—I, p. 63) says of the Hotel-Dieu at Paris: “soldiers and citizens, religious and laymen, Jews and Mohammedans, repaired in ease of need to the Hotel-Dieu, and all were admitted, for all bore the marks of poverty and wretchedness; there was no other requirement.” Moreover, the hospital attendants were obliged at stated times to go out into the streets and bring in those who needed treatment. On entering the hospital, the patient, if a Christian, went to confession and received Holy Communion, in order that peace of mind might benefit bodily health. Once admitted, he was to be treated as the master of the house—quasi dominus secundum posse domus, as the statutes enact. According to their ability, the sick performed the duties of prayer, attendance at Mass, and reception of the sacraments. They were especially recommended to pray for their benefactors, for the authorities, and for all who might be in distress. At night-fall a sort of litany was recited in the wards, each verse of which began: “Seignors malades, proies por”, etc. They were often cheered by the visits of persons in high station or of noble rank and charitable disposition, like Catherine of Sweden, Margaret, Queen of Scotland, Margaret, Duchess of Lorraine, King Louis IX of France.

The regulations concerning the physical wellbeing of the inmates prescribed that the sick should never be left without an attendant—infirmi autem nunquam sint sine vigili custodia (Amiens, XXXV); that nurses should be on duty at all hours of the day and night; that when the illness became serious the patient should be removed from the ward to a private room and receive special attention (Paris, XXII; Troyes, I, XXXIII; Vernon, XI). Santa Maria Nuova at Florence had a separate section (pazzeria) for delirious patients. Similar provision was made for maternity cases, and the patients were kept in the hospital for three weeks after parturition. That due attention was paid to cleanliness and comfort is evident from what the records tell of baths, bed-linens, ventilation, and heating by means of fire-places or braziers.

The medical treatment was given by monks or other ecclesiastics—at least during the earlier period. From the twelfth century onward restrictions were placed on the practice of medicine by clerics, especially in regard to surgical operations, and with still greater severity, in regard to the acceptance of fees for attendance on the sick; see the decrees of the councils: Clermont (1130), can. v; Reims (1131), can. vi; Second Lateran (1139), can. ix; Fourth Lateran (1215), can. xviii. At times a physician or surgeon was called in to render special assistance in certain cases; and this became more general as the medical schools in the universities developed, as at Salerno and Montpellier. An important document is the report sent in 1524 from Santa Maria Nuova in Florence to Henry VIII, who, with a view to reorganizing the London hospitals, had sought information regarding the famous Florentine institution. From this it appears that three young physicians were resident (adstantes) in the hospital, in constant attendance on the sick and made a daily report on the condition of each patient to six visiting physicians from the city who gave prescriptions or ordered modifications in the treatment. Attached to the hospital was a dispensary (medicinarium) for the treatment of ulcers and other slight ailments. This was conducted by the foremost surgeon of the city and three assistants, who gave their services gratuitously to the needy townsfolk and supplied them with remedies from the hospital pharmacy. An interesting account of the apothecary’s duties, with a list of the drugs at his disposal, is given by Lallemand in his interesting work, “L’Histoire de la Charite” (II, 225).

To meet its expenses, each hospital had its own endowment in the shape of lands, sometimes of whole villages, farms, vineyards, and forests. Its revenues were often increased by special taxes on such products as oil, wheat, and salt; by regular contributions from charitable associations; and by the income from churches under its control. In many instances the diocesan laws obliged each of the clergy, especially the canons, to contribute to the support of the hospital. The laity also gave liberally either to the general purposes of the hospital or to supply some special need, such as heating, lighting, or providing for the table. It was not uncommon for a benefactor to donate one or more beds or to establish a life-annuity which secured him care and treatment. The generosity of the hospital and its patrons was frequently abused, e.g. by malingerers or tramps (validi vagrantes), and stricter rules concerning admission became necessary. In some cases the number of attendants was excessive, in others the hospital was unable to provide a separate bed for each patient. In spite of these drawbacks, “we have much to learn from the calumniated Middle Ages—much that we, with far more abundant means, can emulate for the sake of God and of man as well” (Virchow, “Abhandl.”, II, 16).

POST-REFORMATION PERIOD.—The injury inflicted upon the whole system of Catholic charities by the upheaval of the sixteenth century, was disastrous in many ways to the work of the hospitals. The dissolution of the monasteries, especially in England, deprived the Church in large measure of the means to support the sick and of the organization through which those means had been employed. Similar spoliations in Germany followed so rapidly on the introduction of the new religion that the Reformers themselves found it difficult to provide anything like a substitute for the old Catholic foundations. Even Luther confessed more than once that under the papacy generous provision had been made for all classes of suffering, while among his own followers no one contributed to the maintenance of the sick and the poor (Sammtl. Werke, XIV, 389-390; XIII, 224-225). As a result, the hospitals in Protestant countries were rapidly secularized, though efforts were not wanting, on the part of parish and municipality, to provide funds for charitable purposes (Uhlhorn, III).

The Church meanwhile, though deprived of its necessary revenues, took energetic measures to restore and develop the hospital system. The humanist J.L. Vives (De subventione pauperum, Bruges, 1526) declared that by Divine ordinance each must eat his bread after earning it by the sweat of his brow that the magistrates should ascertain by census who among the citizens are able to work and who are really helpless. For the hospitals in particular, Vives urges strict economy in their administration, better provision for medical attendance and a fairer apportionment of available funds whereby the surplus of the wealthier institutions should be assigned to the poorer. Vives’s plan was first put into execution at Ypres in Belgium and then extended by Charles V to his entire empire (1531).

Still more decisive was the action taken by the Council of Trent which renewed the decrees of Vienne and furthermore ordained that every person charged with the administration of a hospital should be held to a strict account and, in case of inefficiency or irregularity in the use of funds, should not only be subject to ecclesiastical censure but should also be removed from office and obliged to make restitution (Session XXV, c. viii, De Reform.). The most important, however, of the Tridentine decrees was that which placed the hospital under episcopal control and proclaimed the right of the bishop to visit each institution in order to see that it is properly managed and that every one connected with it discharges his duties faithfully (Session XXII, c. viii, De Reform.; Session VII, c. xv, De Reform.). These wise enactments were repeated by provincial and diocesan synods throughout Europe. In giving them practical effect St. Charles Borromeo set the example by founding and endowing a hospital at Milan and by obliging hospital directors to submit reports of their administration. He also determined the conditions for the admission of patients in such wise as to exclude undeserving applicants (First Council of Milan, part III, c. i, in Harduin, X, 704). At Rome, the principal foundations during this period were: the hospital established by the Benfratelli in 1581 on the island in the Tiber where the Al sculapium of pagan Rome had stood; the hospital for poor priests founded by a charitable layman, Giovanni Vestri (d. 1650); that of Lorenzo in Fonte (1624) for persons who had spent at least fourteen years in the service of the popes, cardinals, or bishops; that of San Gallicano for skin diseases, erected by Benedict XIII in 1726.

In France the control of the hospitals had already passed into the hands of the sovereign. Louis XIV established in Paris a special hospital for almost every need—invalids, convalescents, incurables etc—besides the vast “hospital general” for the poor. But he withstood the efforts of the episcopate to put in force the Tridentine decrees regarding the superintendence and visitation of the hospitals. On the other hand, this period is remarkable for the results accomplished by St. Vincent de Paul, and especially by the community which he founded to care for the poor sick, the Sisters of Charity (q.v.). Since the Reformation, indeed, women have taken a more prominent part than ever in the care of the sick; over a hundred female orders or congregations have been established for this purpose (see list in Andre-Wagner, “Dict. de droit canonique”, Paris, 1901, II, s.v. Hospitaliers; also articles on the different orders in THE CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA).

A noteworthy attempt at reform during the eighteenth century was that of the Hotel-Dieu at Paris under Louis XVI. This hospital, which usually had 2400 patients and at times 5000, had long suffered from overcrowding, poor ventilation, and neglect of the patients. To remedy these defects, a commission was appointed including Tenon, Lavoisier, and Laplace. The principal recommendation contained in their report (1788) was the adoption of the pavilion system modeled on that of the hospital at Plymouth, England (1764). The French Revolution, however, intervened and it was only during the nineteenth century that the needed improvements were introduced. In the other European countries, meanwhile, there had been many new foundations: in England, Westminster (1719), Guy’s (1722), St. George’s (1733); in Germany, the Charity at Berlin established by Frederick I (1710) and the hospital at Bamberg, by Bishop Franz Ludwig von Erthal (1789); in Austria the General Hospital at Vienna, promoted by Joseph II, 1784.

America.—The first hospital was erected before 1524 in the City of Mexico by Cortes, in gratitude, as he declared in his will, “for the graces and mercies God had bestowed on him in permitting him to discover and conquer New Spain and in expiation or satisfaction for any sins he had committed, especially those that he had forgotten, or any burden these might be on his conscience for which he could not make special atonement”. It was called the Hospital de la Purisima Concepcion, later of Jesus Nazareno, after a neighboring shrine. It is still in existence and its superintendents are appointed by the descendants of Cortes, the Dukes of Terranova y Monteleon. Clement VII by Bull of April 16, 1529, conferred on Cortes the perpetual patronage of this and other similar institutions to be founded by him. Within the first decade after the Conquest, the Hospital of San Lazaro was founded with accommodation for 400 patients, and the Royal Hospital, also in the city of Mexico, was established by a decree of 1540. The law of 1541 ordered hospitals to be erected in all Spanish and Indian towns (Bancroft, “Hist. of Mexico“, II, 169; III, 759). The First Provincial Council of Lima (1583) and the Provincial Council of Mexico (1585) decreed that each priest should contribute the twelfth part of his income to the hospital (D’Aiguirre, “Concil. Hispan.”, IV, 246, 355). The Brothers of St. Hippolytus—a congregation established in 1585 by Bernardin Alvarez, a citizen of Mexico, and approved by Clement VIII in 1594—devoted themselves to the care of the sick and erected numerous hospitals. The Bethlehemites (q.v.), founded by Pedro de Betancourt (d. 1667) and approved by Clement X in 1673, spread from Guatemala over nearly the whole of Latin America, and rendered excellent service by their hospital work until their suppression, as well as all other religious in Mexico, in 1820.

In Canada (q.v.), the earliest foundation was that of the Hotel-Dieu by the Duchess of Aiguillon (q.v.). This was established in 1639 at Sillery, and later transferred to Quebec, where it is still in charge of the Hospitalieres de la Misericorde de Jesus. The Hotel-Dieu at Montreal was founded in 1644 by Jeanne Mance; the General Hospital at Quebec in 1693. There are at present eighty-seven hospitals in Canada under the control and direction of various Catholic religious communities.

The first hospital in the United States was erected on Manhattan Island about 1663 “at the request of Surgeon Hendricksen Varrevanger for the reception of sick soldiers who had been previously billeted on private families, and for the West India Company’s negroes” (Callaghan, “New Netherland Register”). Pesthouses for contagious diseases were established at New York, Salem (Mass.), and Charleston early in the eighteenth century. In 1717 a hospital for infectious diseases was built at Boston. A charter was granted for the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751: the cornerstone was laid in 1755, but the structure was not completed until 1805. The first hospital established by private beneficence was the Charity Hospital at New Orleans, for the founding of which (about 1720) Jean Louis, a sailor, afterwards an officer in the Company of the Indies, left 12,000 livres. This was destroyed by the hurricane of 1779. The New Charity Hospital (San Carlos) was founded in 1780 and endowed by Don Andres de Almonester y Roxas: it became the City Hospital in 1811. Still in charge of the Sisters of Charity, it is one of the most important hospitals in the country, receiving annually about 8000 patients. The oldest hospital in the City of New York is the New York Hospital, founded in 1770 by private subscriptions and by contributions from London. It received from the Provincial Assembly an allowance of £800 for twenty years, and from the State Legislature (1795) an annual allowance of £4000, increased in 1796 to £5000. Bellevue Hospital, originally the infirmary of the New York City Alms House, was erected on its present site in 1811. St. Vincent’s Hospital was opened in 1849; the present buildings were erected 1856-60, and accommodation provided for 140 patients. The average annual number of patients exceeds 5000. There are now more than four hundred Catholic hospitals in the United States, which care for about half a million patients annually.

The multiplication of hospitals in recent times, especially during the nineteenth century, is due to a variety of causes. First among these is the growth of industry and the consequent expansion of city population. To meet the needs of the laboring classes larger hospital facilities have been provided, associations have created funds to secure proper care for sick members, and in some countries (e.g. Germany and England) the insurance of workingmen, as prescribed by law, enables them in case of illness to receive hospital treatment. Another important factor is the advance of medical science, bringing with it the necessity of clinical instruction. In this respect the universities have exerted a wholesome influence: no course in medicine is possible at the present time without that practical training which is to be had in the hospital. Conversely, the efficiency of the hospital has been enhanced by numerous discoveries pertaining to hygiene, anesthetic and antiseptic measures, contagion and infection. The experience of war has also proved beneficial. The lessons learned in the Crimea and in the American Civil War have been applied to hospital construction, and have led to the adoption of the pavilion system. The modern battlefield, moreover, has been the occasion of bringing out in new strength and beauty the spirit of self-sacrifice which animates the hospital orders of the Catholic Church. The services rendered by the sisters to the wounded and dying are conspicuous proof of that Christian charity which from the beginning has striven by all possible means to alleviate human suffering. The hospital of today owes much to scientific progress, generous endowment, and wise administration; but none of these can serve as a substitute for the unselfish work of the men and women who minister to the sick as to the Person of Christ Himself.

JAMES J. WALSH