Councils, GENERAL.—This subject will be treated under the following heads: I. Definition; II. Classification; III. Historical Sketch; IV. The Pope and General Councils; V. Composition of General Councils: (a) Right of participation; (b) Requisite number of members; (c) Papal headship the formal element of Councils; VI. Factors in the Pope‘s Cooperation with the Council: (a) Convocation; (b) Direction; (c) Confirmation; VII. Business Methods: (a) The facts; (b) The theory; VIII. Infallibility of General Councils; IX. Correlation of Papal and Conciliary Infallibility; X. Infallibility Restricted to Unanimous Findings; XI. Promulgation; XII. Is a Council above the Pope? XIII. Has a General Council Power to Depose a Pope?

I. DEFINITION

Councils are legally convened assemblies of ecclesiastical dignitaries and theological experts for the purpose of discussing and regulating matters of church doctrine and discipline. The terms council and synod are synonymous, although in the oldest Christian literature the ordinary meetings for worship are also called synods; and diocesan synods are not properly councils because they are only convened for deliberation. Councils unlawfully assembled are termed conciliabula, conventicula, and even latrocinia, i.e. “robber synods”. The constituent elements of an ecclesiastical council are the following:-

(a) A legally convened meeting of

(b) members of the hierarchy, for

(c) the purpose of carrying out their judicial and doctrinal functions,

(d) by means of deliberation in common,

(e) resulting in regulations and decrees invested with the authority of the whole assembly.

All these elements result from an analysis of the fact that councils are a concentration of the ruling powers of the Church for decisive action.

The first condition is that such concentration conform to the constitution of the Church: it must be started by the head of the forces that are to move and to act, e.g. by the metropolitan if the action is limited to one province. The actors themselves are necessarily the leaders of the Church in their double capacity of judges and teachers, for the proper object of conciliar activity is the settling of questions of faith and discipline. When they assemble for other purposes, either at regular times or in extraordinary circumstances, in order to deliberate on current questions of administration or on concerted action in emergencies, their meetings are not called councils but simply meetings, or assemblies, of bishops. Deliberation, with free discussion and ventilation of private views, is another essential note in the notion of councils. They are the mind of the Church in action, the sensus ecclesi-x taking form and shape in the mould of dogmatic definition and authoritative decrees. The contrast of conflicting opinions, their actual clash, necessarily precedes the final triumph of faith. Lastly, in a council’s decisions we see the highest expression of authority of which its members are capable within the sphere of their jurisdiction, with the added strength and weight resulting from the combined action of the whole body.

II. CLASSIFICATION

Councils are, then, from their nature, a common effort of the Church, or part of the Church, for self-preservation and self-defense. They appear at her very origin, in the time of the Apostles at Jerusalem, and throughout her whole history, whenever faith or morals or discipline are seriously threatened. Although their object is always the same, the circumstances under which they meet impart to them a great variety, which renders a classification necessary. Taking territorial extension for a basis, seven kinds of synods are distinguished:

(1) Ecumenical councils

…are those to which the bishops, and others entitled to vote, are convoked from the whole world under the presidency of the pope or his legates, and the decrees of which, having received papal confirmation, bind all Christians. A council, ecumenical in its convocation, may fail to secure the approbation of the whole Church or of the pope, and thus not rank in authority with ecumenical councils. Such was the case with the Robber Synod of 449 (Latrocinium E phesinum), the Synod of Pisa in 1409, and in part with the Councils of Constance and Basle.

(2) General Synods of the East or of the West

The second rank is held by the general synods of the East or of the West, composed of but one-half of the episcopate. The Synod of Constantinople (381) was originally only an Eastern general synod, at which were present the four patriarchs of the East (viz. of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem), with many metropolitans and bishops. It ranks as ecumenical because its decrees were ultimately received in the West also.

(3) Patriarchal, national, and primatial councils

…represent a whole patriarchate, a whole nation, or the several provinces subject to a primate. Of such councils we have frequent examples in Latin Africa, where the metropolitan and ordinary bishops used to meet under the Primate of Carthage; in Spain, under the Primate of Toledo, and in earlier times in Syria, under the Metropolitan—later Patriarch—of Antioch.

(4) Provincial councils

…bring together the suffragan bishops of the metropolitan of an ecclesiastical province and other dignitaries entitled to participate.

(5) Diocesan synods

…consist of the clergy of the diocese and are presided over by the bishop or the vicar-general.

A peculiar kind of council used to be held at Constantinople; it consisted of bishops from any part of the world who happened to be at the time in that imperial city. Hence the name “visitors’ synods”.

Lastly there have been mixed synods, in which both civil and ecclesiastical dignitaries met to settle secular as well as ecclesiastical matters. They were frequent at the beginning of the Middle Ages in France, Germany, Spain, and Italy. In England even abbesses were occasionally present at such mixed councils. Sometimes, not always, the clergy and laity voted in separate chambers

Although it is in the nature of councils to represent either the whole or part of the Church organism yet we find many councils simply consisting of a number of bishops brought together from different countries for some special purpose, regardless of any territorial or hierarchical connection. They were most frequent in the fourth century, when the metropolitan and patriarchal circumscriptions were still imperfect, and questions of faith and discipline manifold. Not a few of them, summoned by emperors or bishops in opposition to the lawful authorities (such as that of Antioch in 341), were positively irregular, and acted for evil rather than good. Councils of this kind may be compared to the meetings of bishops of our own times; decrees passed in them had no binding power on any but the subjects of the bishops present; they were important manifestations of the sensus ecclesice (mind of the Church) rather than judicial or legislative bodies. But precisely as expressing the mind of the Church they often acquired a far-reaching influence due, either to their internal soundness, or to the authority of their framers, or to both.

It should be noted that the terms concilia plenaria, universalia, or generaliaare, or used to be, applied indiscriminately to all synods not confined to a single province; in the Middle Ages, even provincial synods, as compared to diocesan, received these names. Down to the late Middle Ages all papal synods to which a certain number of bishops from different countries had been summoned were regularly styled plenary, general, or universal synods. In earlier times, before the separation of East and West, councils to which several distant patriarchates or exarchates sent representatives, were described absolutely as “plenary councils of the universal Church“. These terms are applied by St. Augustine to the Council of Arles (314), at which only Western bishops were present. In the same way the Council of Constantinople (382), in a letter to Pope Damasus, calls the council held in the same town the year before (381) “an ecumenical synod” the whole inhabited world as known to the Greeks and Romans, because all the Eastern patriarchates, though no Western, took part in it. The synod of 381 could not, at that time, be termed ecumenical in the strict sense now in use, because it still lacked the formal confirmation of the Apostolic See. As a matter of fact, the Greeks themselves did not put this council on a par with those of Nicaea and Ephesus until its confirmation at the Synod of Chalcedon, and the Latins acknowledged its authority only in the sixth century.

III. HISTORICAL SKETCH OF ECUMENICAL COUNCILS

The present article deals chiefly with the theological and canonical questions concerning councils which are ecumenical in the strict sense above defined. Special articles give the history of each important synod under the head of the city or see where it was held. In order, however, to supply the reader with a basis of fact for the discussion of principles which is to follow, a list is subjoined of the twenty ecumenical councils with a brief statement of the purpose of each.

The First Ecumenical, or Council of Nicaea (325) lasted two months and twelve days. Three hundred and eighteen bishops were present. Hosius, Bishop of Cordova, assisted as legate of Pope Sylvester. The Emperor Constantine was also present. To this council we owe the Creed (Symbolum) of Nicaea, defining against Arius the true Divinity of the Son of God (homoousios), and the fixing of the date for keeping Easter (against the Quartodecimans).

The Second Ecumenical, or First General Council of Constantinople (381), under Pope Damasus and the Emperor Theodosius I, was attended by 150 bishops. It was directed against the followers of Macedonius, who impugned the Divinity of the Holy Ghost. To the above-mentioned Nicene Creed it added the clauses referring to the Holy Ghost (qui simul adoratur) and all that follows to the end.

The Third Ecumenical, or Council of Ephesus (431), of more than 200 bishops, presided over by St. Cyril of Alexandria representing Pope Celestine I, defined the true personal unity of Christ, declared Mary the Mother of God (theotokos) against Nestorius, Bishop of Constantinople, and renewed the condemnation of Pelagius.

The Fourth Ecumenical, or Council of Chalcedon (451)—150 bishops under Pope Leo the Great and the Emperor Marcian—defined the two natures (Divine and human) in Christ against Eutyches, who was excommunicated.

The Fifth Ecumenical, or Second General Council of Constantinople (553), of 165 bishops under Pope Vigilius and Emperor Justinian I, condemned the errors of Origen and certain writings (The Three Chapters) of Theodoret, of Theodore, Bishop of Mopsuestia, and of Ibas, Bishop of Edessa; it further confirmed the first four general councils, especially that of Chalcedon whose authority was contested by some heretics.

The Sixth Ecumenical, or Third Council of Constantinople (680-681), under Pope Agatho and the Emperor Constantine Pogonatus, was attended by the Patriarchs of Constantinople and of Antioch, 174 bishops, and the emperor. It put an end to Monothelism by defining two wills in Christ, the Divine and the human, as two distinct principles of operation. It anathematized Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul, Macarius, and all their followers.

The Seventh Ecumenical, or Second Council of Nicena (787) was convoked by Emperor Constantine VI and his mother Irene, under Pope Adrian I, and was presided over by the legates of Pope Adrian; it regulated the veneration of holy images. Between 300 and 367 bishops assisted.

The Eighth Ecumenical, or Fourth Council of Constantinople (869), under Pope Adrian II and Emperor Basil, numbering 102 bishops, 3 papal legates, and 4 patriarchs, consigned to the flames the Acts of an irregular council (conciliabulum) brought together by Photius against Pope Nicholas and Ignatius, the legitimate Patriarch of Constantinople; it condemned Photius who had unlawfully seized the patriarchal dignity. The Photian schism, however, triumphed in the Greek Church, and no other general council took place in the East.

The Ninth Ecumenical Council (1123) was the first held in the Lateran at Rome under Pope Callistus II. About 900 bishops and abbots assisted. It abolished the right, claimed by lay princes, of investiture with ring and crosier to ecclesiastical benefices and dealt with church discipline and the recovery of the Holy Land from the infidels.

The Tenth Ecumenical Council (1139) was the Second Lateran held at Rome under Pope Innocent II with an attendance of about 1000 prelates and the Emperor Conrad. Its object was to put an end to the errors of Arnold of Brescia.

The Eleventh Ecumenical Council (1179) was the third assembled at the Lateran, and took place under Pope Alexander III, Frederick I being emperor. There were 302 bishops present. It condemned the Albigenses and Waldenses and issued numerous decrees for the reformation of morals.

The Twelfth Ecumenical Synod (1215) was the Fourth Lateran, under Innocent III. There were present the Patriarchs of Constantinople and Jerusalem, 71 archbishops, 412 bishops, and 800 abbots, the Primate of the Maronites, and St. Dominic. It issued an enlarged creed (symbol) against the Albigenses (Firmiter credimus), condemned the Trinitarian errors of Abbot Joachim, and published 70 important reformatory decrees. This is the most important council of the Middle Ages; it marks the culminating point of ecclesiastical life and papal power.

The First General Council of Lyons (1245) is the Thirteenth Ecumenical. Innocent IV presided; the Patriarchs of Constantinople, Antioch, and Aquileia (Venice), 140 bishops, Baldwin II, Emperor of the East, and St. Louis, King of France, assisted. It excommunicated and deposed Emperor Frederick II and directed a new crusade, under the command of St. Louis, against the Saracens and Mongols.

The Fourteenth Ecumenical Council was held at Lyons (1274) by Pope Gregory X, the Patriarchs of Antioch and Constantinople, 15 cardinals, 500 bishops, and more than 1000 other dignitaries. It effected a temporary reunion of the Greek Church with Rome. The word filioque was added to the symbol of Constantinople and means were sought for recovering Palestine from the Turks. It also laid down the rules for papal elections.

The Fifteenth Ecumenical Council took place at Vienne in France (1311-1313) by order of Clement V, the first of the Avignon popes. The Patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria, 300 bishops (114 according to some authorities), and 3 kings—Philip IV of France, Edward II of England, and James II of Aragon—were present. The synod dealt with the crimes and errors imputed to the Knights Templars, the Fraticelli, the Beghards, and the Beguines, with projects of a new crusade, the reformation of the clergy, and the teaching of Oriental languages in the universities.

The Council of Constance (1414-1418), the Sixteenth Ecumenical, was held during the great Schism of the West, with the object of ending the divisions in the Church. It only became legitimate when Gregory XII had formally convoked it. Owing to this circumstance it succeeded in putting an end to the schism by the election of Pope Martin V, which the Council of Pisa (1409) had failed to accomplish on account of its illegality. The rightful pope confirmed the former decrees of the synod against Wyclif and Hus. This council is thus only ecumenical in its last sessions (XLII-XLV inclusive) and with respect to the decrees of earlier sessions approved by Martin V.

The Seventeenth Ecumenical Council met at Basle (1431), Eugene IV being pope, and Sigismund Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Its object was the religious pacification of Bohemia. Quarrels with the pope having arisen, the council was transferred first to Ferrara (1438), then to Florence (1439), where a short-lived union with the Greek Church was effected, the Greeks accepting the council’s definition of controverted points. The Council of Basle is only ecumenical till the end of the twenty-fifth session, and of its decrees Eugene IV approved only such as dealt with the extirpation of heresy, the peace of Christendom, and the reform of the Church, and which at the same time did not derogate from the rights of the Holy See.

The Eighteenth Ecumenical, or Fifth Council of the Lateran, sat from 1512 to 1517 under Popes Julius II and Leo X, the emperor being Maximilian I. Fifteen cardinals and about eighty archbishops and bishops took part in it. Its decrees are chiefly disciplinary. A new crusade against the Turks was also planned, but came to naught, owing to the religious upheaval in Germany caused by Luther.

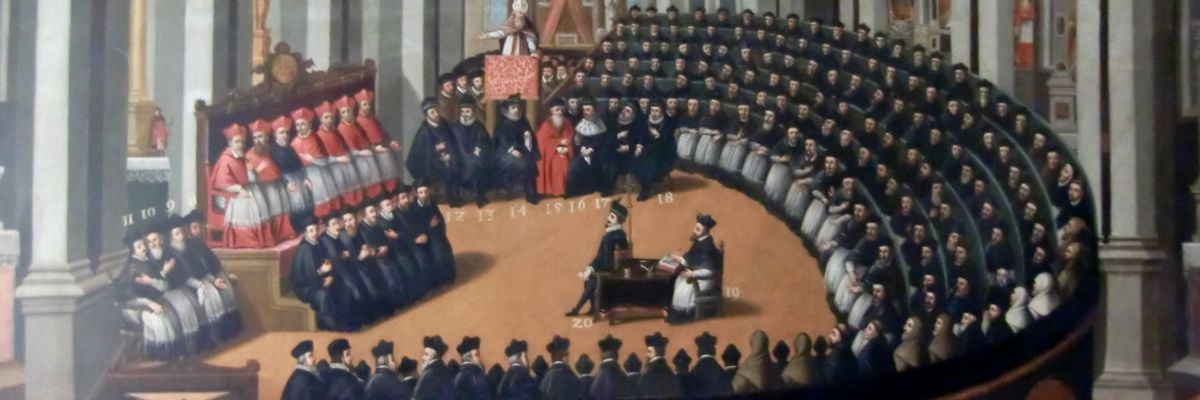

The Council of Trent, the Nineteenth Ecumenical, lasted eighteen years (1545-1563) under five popes: Paul III, Julius III, Marcellus II, Paul IV, and Pius IV, and under the Emperors Charles V and Ferdinand. There were present 5 cardinal legates of the Holy See, 3 patriarchs, 33 archbishops, 235 bishops, 7 abbots, 7 generals of monastic orders, 160 doctors of divinity. It was convoked to examine and condemn the errors promulgated by Luther and other Reformers, and to reform the discipline of the Church. Of all councils it lasted longest, issued the largest number of dogmatic and reformatory decrees, and produced the most beneficial results.

The Twentieth Ecumenical Council was summoned to the Vatican by Pius IX. It met December 8, 1869, and lasted till July 18, 1870, when it was adjourned; it is still (1908) unfinished. There were present 6 archbishop-princes, 49 cardinals, 11 patriarchs, 680 archbishops and bishops, 28 abbots, 29 generals of orders, in all 803. Besides important canons relating to the Faith and the constitution of the Church, the council decreed the infallibility of the pope when speaking ex cathedra, i.e. when, as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole Church.

IV. THE POPE AND GENERAL COUNCILS

The relations between the pope and general councils must be exactly defined to arrive at a just conception of the functions of councils in the Church, of their rights and duties, and of their authority. The traditional phrase, “the council represents the Church“, associated with the modern notion of representative assemblies, is apt to lead to a serious misconception of the bishops’ function in general synods. The nation’s deputies receive their power from their electors and are bound to protect and promote their electors’ interests; in the modern democratic State they are directly created by, and out of, the people’s own power. The bishops in council, on the contrary, hold no power, no commission, or delegation, from the people. All their powers, orders, jurisdiction, and membership in the council, come to them from above—directly from the pope, ultimately from God. What the episcopate in council does represent is the Divinely instituted magisterium, the teaching and governing power of the Church; the interests it defends are those of the depositum fidei, of the revealed rules of faith and morals, i.e. the interests of God.

The council is, then, the assessor of the supreme teacher and judge sitting on the Chair of Peter by Divine appointment; its operation is essentially cooperation—the common action of the members with their head—and therefore necessarily rises or falls in value, according to the measure of its connection with the pope. A council in opposition to the pope is not representative of the whole Church, for it neither represents the pope who opposes it, nor the absent bishops, who cannot act beyond the limits of their dioceses except through the pope. A council not only acting independently of the Vicar of Christ, but sitting in judgment over him, is unthinkable in the constitution of the Church; in fact, such assemblies have only taken place in times of great constitutional disturbances, when either there was no pope or the rightful pope was indistinguishable from antipopes. In such abnormal times the safety of the Church becomes the supreme law, and the first duty of the abandoned flock is to find a new shepherd, under whose direction the existing evils may be remedied.

In normal times, when according to the Divine constitution of the Church, the pope rules in the fullness of his power, the function of councils is to support and strengthen his rule on occasions of extraordinary difficulties arising from heresies, schisms, relaxed discipline, or external foes. General councils have no part in the ordinary normal government of the Church. This principle is confirmed by the fact that during nineteen centuries of Church life only twenty ecumenical councils took place. It is further illustrated by the complete failure of the decree issued in the thirty-ninth session of the Council of Constance (then without a rightful head), to the effect that general councils should meet frequently and at regular intervals; the very first synod summoned at Pavia for the year 1423 could not be held for want of responses to the summons. It is thus evident that general councils are not qualified to issue, independently of the pope, dogmatic or disciplinary canons binding on the whole Church. As a matter of fact, the older councils, especially those of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), were not convened to decide on questions of faith still open, but to give additional weight to, and secure the execution of, papal decisions previously issued and regarded as fully authoritative. The other consequence of the same principle is that the bishops in council assembled are not commissioned, as are our modern parliaments, to control and limit the power of the sovereign, or head of the State, although circumstances may arise in which it would be their right and duty firmly to expostulate with the pope on certain of his acts or measures. The severe strictures of the Sixth General Council on Pope Honorius I may be cited as a case in point.

V. COMPOSITION OF GENERAL COUNCILS

(a) Right of participation

The right to be present and to act at general councils belongs in the first place and logically to the bishops actually exercising the episcopal office. In the earlier councils there appear also the chorepiscopi (country-bishops), who, according to the better opinion, were neither true bishops nor an order interposed between bishops and priests, but priests invested with a jurisdiction smaller than the episcopal but larger than the sacerdotal. They were ordained by the bishop and charged with the administration of a certain district in his diocese. They had the power of conferring minor orders, and even the subdiaconate. Titular bishops, i.e. bishops not ruling a diocese, had equal rights with other bishops at the Vatican Council (1869-70), where 117 of them were present. Their claim lies in the fact that their order, the episcopal consecration, entitles them, jure divine, to take part in the administration of the Church, and that a general council seems to afford a proper sphere for the exercise of a right which the want of a proper diocese keeps in abeyance. Dignitaries who hold episcopal or quasi-episcopal jurisdiction without being bishops—such as cardinal-priests, cardinal-deacons, abbots nullius, mitred abbots of whole orders or congregations of monasteries, generals of clerks regular, mendicant and monastic orders—were allowed to vote at the Vatican Council. Their title is based on positive canon law: at the early councils such votes were not admitted, but from the seventh century down to the end of the Middle Ages the contrary practice gradually prevailed, and has since become an acquired right. Priests and deacons frequently cast decisive votes in the name of absent bishops whom they represented; at the Council of Trent, however, such procurators were admitted only with great limitations, and at the Vatican Council they were even excluded from the council hall.

Besides voting members, every council admits, as consulters, a number of doctors in theology and canon law. In the Council of Constance the consulters were allowed to vote. Other clerics have always been admitted as notaries. Lay people may be, and have been, present at councils for various reasons, but never as voters. They gave advice, made complaints, assented to decisions, and occasionally also signed the decrees. Since the Roman emperors had accepted Christianity, they assisted either personally or through deputies (commissarii). Constantine the Great was present in person at the First General Council; Theodosius II sent his representatives to the third, and Emperor Marcian sent his to the fourth, at the sixth session of which himself and the Empress Pulcheria assisted personally. Constantine Pogonatus was present at the sixth; the Empress Irene and her son Constantine Porphyrogenitus only sent their representative to the seventh, whereas Emperor Basil, the Macedonian, assisted at the eighth, sometimes in person, sometimes through his deputies. Only the Second and the Fifth General Synods were held in the absence of the emperors or imperial commissaries, but both Theodosius the Great and Justinian were at Constantinople while the councils were sitting, and kept up constant intercourse with them. In the West the attendance of kings, even at provincial synods, was of frequent occurrence. The motive and object of the royal presence were to protect the synods, to heighten their authority, to lay before them the needs of particular Christian states and countries.

This laudable and legitimate cooperation led by degrees to interference with the pope’s rights in conciliar matters. The Eastern Emperor Michael claimed the right to summon councils without obtaining the pope’s consent, and to take part in them personally or by proxy. But Pope Nicholas I resisted the pretensions of Emperor Michael, pointing out to him, in a letter (865), that his imperial predecessors had only been present at general synods dealing with matters of faith, and from that fact drew the conclusion that all other synods should be held without the emperor’s or his commissaries’ presence. A few years later the Eighth General Synod (Can. xvii, Hefele, IV, 421) declared it false that no synod could be held with-out the emperor’s presence—the emperors had only been present at general councils—and that it was not right for secular princes to witness the condemnation of ecclesiastics (at provincial synods). As early as the fourth century the bishops greatly complained of the action of Constantine the Great in imposing his commissary on the Synod of Tyre (335). In the West, however, secular princes were present even at national synods, e.g. Sisenand, King of the Spanish Visigoths, was at the Fourth Council of Toledo (636) and King Chintilian at the fifth (638); Charlemagne assisted at the Council of Frankfort (794) and two Anglo-Saxon kings at the Synod of Whitby (Collatio Pharen sis) in 664. But step by step Rome established the principle that no royal commissary may be present at any council, except a general one, in which “faith, reformation, and peace” are in question.

(b) Requisite number of members

The number of bishops present required to constitute an ecumenical council cannot be strictly defined, nor need it be so defined, for ecumenicity chiefly depends on cooperation with the head of the Church, and only secondarily on the number of cooperators. It is physically impossible to bring together all the bishops of the world, nor is there any standard by which to determine even an approximate number, or proportion, of prelates necessary to secure ecumenicity. All should be invited, no one should be debarred, a somewhat considerable number of representatives of the several provinces and countries should he actually present: this may be laid down as a practicable theory. But the ancient Church did not conform to this theory. As a rule only the patriarchs and metropolitans received a direct summons to appear with a certain number of their suffragans. At Ephesus and Chalcedon the time between the convocation and the meeting of the council was too short to allow of the Western bishops being invited. As a rule, but very few Western bishops were personally present at any of the first eight general synods. Occasionally, e.g. at the sixth, their absence was remedied by sending deputies with precise instructions arrived at in a previous council held in the West. What gives those Eastern synods their ecumenical character is the cooperation of the pope as head of the universal, and, especially, of the Western, Church. This circumstance, so remarkably prominent in the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, affords the best proof that, in the sense of the Church, the essential constituent element of ecumenicity is less the proportion of bishops present to bishops absent than the organic connection of the council with the head of the Church.

(c) Papal headship the formal element of councils

It is the action of the pope that makes the councils oecumenic. That action is the exercise of his office of supreme teacher and ruler of the Church. Its necessity results from the fact that no authority is commensurate with the whole Church except that of the pope; he alone can bind all the faithful. Its sufficiency is equally manifest: when the pope has spoken ex cathedra to make his own the decisions of any council, regardless of the number of its members, nothing further can be wanted to make them binding on the whole Church. The earliest enunciation of the principle is found in the letter of the Council of Sardica (343) to Pope Julius I, and was often quoted, since the beginning of the fifth century, as the (Nican) canon concerning the necessity of papal cooperation in all the more important conciliary Acts. The Church historian Socrates (Hist. Eccl., II, xvii) makes Pope Julius say, in reference to the Council of Antioch (341), that the law of the Church (scud’s) forbids “the churches to pass laws contrary to the judgment of the Bishop of Rome“, and Sozomen (III, x) likewise declares “it to be a holy law not to attribute any value to things done without the judgment of the Bishop of Rome“. The letter of Julius here quoted by both Socrates and Sozomen directly refers to an existing ecclesiastical custom, and, in particular, to a single important case (the deposition of a patriarch), but the underlying principle is as stated.

Papal cooperation may be of several degrees: to be effective in stamping a council as universal it must amount to taking over responsibility for its decisions by giving them formal confirmation. The Synod of Constantinople (381) in which the Nicene Creed received its present form—the one used at Mass—had in itself no claim to be ecumenical. Before Pope Damasus and the Western bishops had seen its full Acts they condemned certain of its proceedings at an Italian synod, but on receiving the Acts, Damasus, so we are told by Photius, confirmed them. Photius, however, is only right with regard to the Creed, or Symbol of Faith: the canons of this council were still rejected by Leo the Great and even by Gregory the Great (about 600). A proof that the Creed of Constantinople enjoyed papal sanction may be drawn from the way in which the Roman legates at the Fourth General Synod (Chalcedon, 451) allowed, without any protest, appeals to this Creed, while at the same time they energetically protested against the canons of the council. It was on account of the papal approbation of the Creed that, in the sixth century, Popes Vigilius, Pelagius II, and Gregory the Great declared this council (ecumenical, although Gregory still refused to sanction its canons. The First Synod of Constantinople presents, then, an instance of a minimum of papal cooperation impressing on a particular council the mark of universality. The normal cooperation, however, requires on the part of the head of the Church more than a post-factum acknowledgment.

The pope’s office and the council’s function in the organization of the Church require that the pope should call the council together, preside over and direct its labors, and finally promulgate its decrees to the universal Church as expressing the mind of the whole teaching body guided by the Holy Ghost. Instances of such normal, natural, perfect cooperation occur in the five Lateran councils, which were presided over by the pope in person; the personal presence of the highest authority in the Church, his direction of the deliberations, and approbation of the decrees, stamp the conciliary proceedings throughout as the function of the Magisterium Ecclesice in its most authoritative form. Councils in which the pope is represented by legates are, indeed, also representative of the whole teaching body of the Church, but the representation is not absolute or adequate, is no real concentration of its whole authority. They act in the name, but not with the whole power, of the teaching Church, and their decrees become universally binding only through an act, either antecedent or consequent, of the pope. The difference between councils presided over personally and by proxy is marked in the form in which their decrees are promulgated: when the pope has been present the decrees are published in his own name with the additional formula: sacro approbante Concilio; when papal legates have presided the decrees are attributed to the synod (S. Synodus declarat, definit, decernit).

VI. FACTORS IN THE POPE’S CO-OPERATION WITH THE COUNCIL

We have seen that no council is ecumenical unless the pope has made it his own by cooperation, which admits of a minimum and a maximum, consequently of various degrees of perfection. Catholic writers could have saved themselves much trouble if they had always based their apologetics on the simple and evident principle of a sufficient mini-mum of papal cooperation, instead of endeavoring to prove, at all costs, that a maximum is both required in principle and demonstrable in history. The three factors constituting the solidarity of pope and council are the convocation, direction, and confirmation of the council by the pope; but it is not essential that each and all of these factors should always be present in full perfection.

(a) Convocation

The juridical convocation of a council implies something more than an invitation addressed to all the bishops of the world to meet in council, viz.: the act by which in law the bishops are bound to take part in the council, and the council itself is constituted a legitimate tribunal for dealing with Church affairs. Logically, and in the nature of the thing, the right of convocation belongs to the pope alone. Yet the convocation, in the loose sense of invitation to meet, of the first eight general synods, was regularly issued by the Christian emperors, whose dominion was coextensive with the Church, or at least with the Eastern part of it, which was then alone convened. The imperial letters of convocation to the Councils of Ephesus (Hardouin, I, 1343) and of Chalcedon (Hardouin, II, 42) show that the emperors acted as protectors of the Church, believing it their duty to further by every means in their power the welfare of their charge. Nor is it possible in every case to prove that they acted at the formal instigation of the pope; it even seems that the emperors more than once followed none but their own initiative for convening the council and fixing its place of meeting. It is, however, evident that the Christian emperors cannot have acted thus without the consent, actual or presumed, of the pope. Otherwise their conduct had been neither lawful nor wise. As a matter of fact, none of the eight Eastern ecumenical synods, with the exception, perhaps, of the fifth, was summoned by the emperor in opposition to the pope. As regards the fifth, the conduct of the emperor caused the legality of the council to be questioned—a proof that the mind of the Church required the pope’s consent for the lawfulness of councils. As regards most of these eight synods, particularly that of Ephesus, the previous consent of the pope, actual or presumed, is manifest. Regarding the convocation of the Council of Chalcedon, the Emperor Marcian did not quite fall in with the wishes of Pope Leo I as to the time and place of its meeting, but he did not claim an absolute right to have his will, nor did the pope acknowledge such a right. On the contrary, as Leo I explains in his letters (Epp. lxxxix, xc, ed. Ballerini), he only submitted to the imperial arrangements because he was unwilling to interfere with Martian’s well-meant endeavors.

It is still more evident that convocation by the emperors did not imply on their part the claim to constitute the council juridically, that is, to give it power to sit as an authorized tribunal for Church affairs. Such a claim has never been put forward. The expressions jubere and GKKEXEVELV, occasionally used in the wording of the convocation, do not necessarily convey the notion of strict orders not to be resisted; they also have the meaning of exhorting, inducing, bidding. The juridical constitution of the council could only emanate, and in fact always did emanate, from the Apostolic See. As the necessity of the bishops’ meeting in council was dictated rather by the distressful condition of the Church than by positive orders, the pope contented himself with authorizing the council, and this he effected by sending his legates to preside over and direct the work of the assembled prelates. The Emperor Marcian in his first letter to Leo I declares that the success of the intended synod depends on his—the pope’s—authorization, and Leo, not Marcian, is later called the auctor synodi without any restrictive qualification, especially at the time of the “Three Chapters” dispute, where the extension of the synod’s authority was called in question. The law therefore, at that period was the same as it is now as far as essentials are concerned: the pope is the sole convener of the council as an authoritative juridical assembly. The difference lies in the circumstance that the pope left to the emperor the execution of the convocation and the necessary measures for rendering the meeting possible and surrounding it with the eclat due to its dignity in Church and State. The material, or business, part of the councils being thus entirely in the hands of the emperors, it was to be expected that the pope was sometimes induced—if not forced—by circumstances to make his authorization suit the imperial wishes and arrangements.

After studying the principles it is well to see how they worked out in fact. Hence the following historical summary of the convocation of the first eight general councils:

(1) Eusebius (Vita Constantini, III, vi) informs us that the writs of convocation to the First General Synod were issued by Emperor Constantine, but as not one of those writs has come down to us, it remains doubtful whether or not they mentioned any previous consultation with the pope. It is, however, an undeniable fact that the Sixth General Synod (680) plainly affirmed that the Council of Nica had been convened by the emperor and Pope Sylvester (Mani, Coll. Cone., XI, 661). The same statement appears in the life of Sylvester found in the “Liber Pontificalis“, but this evidence need not be pressed, the evidence from the council being, from the circumstances in which it was given, of sufficient strength to carry the point. For the Sixth General Council took place in Constantinople, at a time when the bishops of the imperial city already attempted to rival the bishops of Old Rome, and the vast majority of its members were Greeks; their statement is therefore entirely free from the suspicion of Western ambition or prejudice and must be accepted as a true presentment of fact. Rufinus, in his continuation of Eusebius’ history (I, 1) says that the emperor summoned the synod ex sacerdotum sententia (on the advice of the clergy); it is but fair to suppose that if he consulted several prelates he did not omit to consult with the head of all.

The Second General Synod (381) was not, at first, intended to be ecumenical; it only became so because it was accepted in the West, as has been shown above. It was not summoned by Pope Damasus, as is often contended, for the assertion that the assembled bishops professed to have met in consequence of a letter of the pope to Theodosius the Great is based on a confusion. The document here brought in as evidence refers to the synod of the following year which was indeed summoned at the instigation of the pope and the Synod of Aquileia, but was not an ecumenical synod.

The Third General Council (Ephesus, 431) was convoked by Emperor Theodosius II and his Western colleague Valentinian III; this is evident from the Acts of the council. It is equally evident that Pope Celestine I gave his consent, for he wrote (May 15, 431) to Theodosius that he could not appear in person at the synod, but that he would send his representatives. And in his epistle of May 8 to the synod itself, he insists on the duty of the bishops present to hold fast to the orthodox faith, expects them to accede to the sentence he has already pronounced on Nestorius, and, adds that he has sent his legates to execute that sentence at Ephesus. The members of the council acknowledge the papal directions and orders, not only the papal consent, in the wording of their solemn condemnation of Nestorius: “Urged by the Canons and conforming to the Letter of our most holy Father and fellow servant Celestine the Roman bishop, we have framed this sorrowful sentence against Nestorius.” They express the same sentiment where they say that “the epistle of the Apostolic See (to Cyril, communicated to the council) already contains a judgment and a rule on the case of Nestorius”, and that they—the bishops in council—have executed that ruling. All this manifests the bishops’ conviction that the pope was the moving and quickening spirit of the synod.

How the Fourth General Synod (Chalcedon, 451) was brought together is set forth in several writings of Pope Leo I and Emperors Theodosius II and Marcian. Immediately after the Robber Synod, Leo asked Theodosius to prepare a council composed of bishops from all parts of the world, to meet, preferably, in Italy. He repeated the same request, first made October 13, 449, on the following feast of Christmas, and prevailed on the Western Emperor Valentinian III together with his empress and his mother, to support it at the Byzantine Court. Once more (in July, 450) Leo renewed his request, adding, however, that the council might be dispensed with if all the bishops were to make a profession of the orthodox faith without being united in council. About this time Theodosius II died and was succeeded by his sister, St. Pulcheria, and her husband Marcian. Both at once informed the pope of their willingness to summon the council, Marcian specially asking him to state in writing whether he could assist at the synod in person or through his legates, so that the necessary writs of convocation might be issued to the Eastern bishops. By that time, however, the situation had greatly improved in the Eastern Church; nearly all the bishops who had taken part in the Robber Synod had now repented of their aberration and signed, in union with their orthodox colleagues, the “Epistola dogmatica” of Leo to Flavian, by this act rendering the need of a council less urgent. Besides, the Huns were just then invading the West, preventing many Latin bishops, whose presence at the council was most desirable, from leaving their flocks to undertake the long journey to Chalcedon. Other motives induced the pope to postpone the synod, e.g. the fear that it might be made the occasion by the bishops of Constantinople to improve their hierarchical position, a fear well justified by subsequent events. But Marcian had already summoned the synod, and Leo therefore gave his instructions as to the business to be transacted. He was then entitled to say, in a letter to the bishops who had been at the council that the synod had been brought together “ex praecepto christianorum principum et ex consensu apostolicae sedis” (by order of the Christian princes and with the consent of the Apostolic See). The emperor himself wrote to Leo that the synod had been held by his authority (te auctore), and the bishops of Mcesia, in a letter to the Byzantine Emperor Leo, said: “At Chalcedon many bishops assembled by order of Leo, the Roman pontiff, who is the true head of the bishops”.

The Fifth General Synod was planned by Justinian I with the consent of Pope Vigilius (q.v.), but on account of the emperor’s dogmatic pretensions, quarrels arose and the pope refused to be present, although repeatedly invited. His Constitutum of May 14, 553, to the effect that he could not consent to anathematize Theodore of Mopsuestia and Theodoret, led to open opposition between pope and council. In the end all was righted by Vigilius approving the synodal decrees.

(6, 7, 8) These three synods were each and all called by the emperors of the time with the consent and assistance of the Apostolic See. (See Councils of Constantinople; Councils of Nicaea.)

(b) Direction.—The direction or presidency of councils belongs to the pope by the same right as their convocation and constitution. Were a council directed in its deliberations and acts by anyone independent of the pope and acting entirely on his own responsibility, such a council could not be the pope’s own in any sense: the defect could only be made good by a consequent formal act of the pope accepting responsibility for its decisions. In point of fact, papal legates presided over all the Eastern councils, which from their beginning were legally constituted. The reader will obtain a clearer insight into this point of conciliar proceedings from a concrete example, taken from Hefele’s introduction to his “History of the Councils”:

Pope Adrian II sent his legates to the Eighth I: Ecumenical Synod (787) with an express declaration to the Emperor Basil that they were to act as presidents of the council. The legates, Bishop Donatus of Ostia, Bishop Stephen of Nepesina, and the deacon Marinus of Rome, read the papal rescript to the synod. Not the slightest objection was raised. Their names took precedence in all protocols; they determined the duration of the several sessions, gave leave to make speeches and to read documents and to admit other persons; they put the leading questions, etc. In short, their presidency in the first five sessions cannot be disputed. But at the sixth session Emperor Basil was present with his two sons, Constantine and Leo, and, as the Acts relate, received the presidency. These same Acts, however, at once clearly distinguish the emperor and his sons from the synod when, after naming them, they continue: conveniente sancta ac universali synodo (the holy and universal synod now meeting), thus disassociating the lay ruler from the council proper. The names of the papal legates continue to appear first among the members of the synod, and it is they who in those latter sessions determine the matters for discussion, subscribe the Acts before anyone else, expressly as presidents of the synod, whereas the emperor, to show clearly that he did not consider himself the president, would only subscribe after all the bishops. The papal legates begged him to put his and his son’s names at the head of the list, but he stoutly refused and only consented, at last, to write his name after those of the papal legates and of the Eastern patriarchs, but before those of the bishops. Consequently Pope Adrian II, in a letter to the emperor, praises him for not having assisted at the council as a judge (judex), but merely as a witness and protector (conscius et obsecundator).

The imperial commissaries present at the synod acted even less as presidents than the emperor himself. They signed the reports of the several sessions only after the representatives of the patriarchs, though before the bishops; their names are absent from the signatures of the Acts. On the other hand it may be contended that the Eastern patriarchs, Ignatius of Constantinople, and the representatives of the other Eastern patriarchs, in some degree participated in the presidency: their names are constantly associated with those of the Roman legates and clearly distinguished from those of the other metropolitans and bishops. They, as it were, form with the papal legates a board of directors, fix with him the order of proceedings, determine who shall be heard, subscribe, like the legates, before the emperor, and are entered in the reports of the several sessions before the imperial commissaries. All this being granted, the fact still remains that the papal legates unmistakably hold the first place, for they are always named first and sign first, and—a detail of great importance—for the final subscription they use the formula: huic sanctae et universali synodo pressidens (presiding over this holy and universal synod), while Ignatius of Constantinople and the representatives of the other patriarchs claim no presidency, but word their subscription thus: suscipiens et omnibus quae ab ed judicata et scripta sunt concordans et definiens subscripsi (receiving this holy and universal synod and agreeing with all it has judged and written, and defining I have signed). If, on the one hand, this form of subscription differs from that of the president, it differs no less, on the other, from that of the bishops. These, like the emperor, have without exception used the formula: suscipiens (synodum) subscripsi (receiving the synod I have signed), omitting the otherwise customary definiens, which was used to mark a decisive vote (votum decisivum).

Hefele gives similar documentary accounts of the first eight general synods, showing that papal legates always presided over them when occupied in their proper business of deciding questions on faith and discipline. The exclusive right of the pope in this matter was generally acknowledged. Thus, the Emperor Theodosius II says, in his edict addressed to the Council of Ephesus, that he had sent Count Candidian to represent him, but that this imperial commissary was to take no part in dogmatic disputes since “it was unlawful for one who is not enrolled in the lists of the most holy bishops to mingle in ecclesiastical inquiries”. The Council of Chalcedon acknowledged that Pope Leo, by his legates, presided over it as “the head over the members”. At Nica, Hosius, Vitus, and Vincentius, as papal legates, signed before all other members of the council. The right of presiding and directing implies that the pope, if he chooses to make a full use of his powers, can determine the subject matter to be dealt with by the council, prescribe rules for conducting the debates, and generally order the whole business as seems best to him. Hence no conciliar decree is legitimate if carried under protest—or even without the positive consent—of the pope or his legates. The consent of the legates alone, acting without a special order from the pope, is not sufficient to make conciliar decrees at once perfect and operative; what is necessary is the pope’s own consent. For this reason no decree can become illegitimate and null in law on account of pressure brought to bear on the assembly by the presiding pope, or by papal legates acting on his orders. Such pressure and restriction of liberty, proceeding from the internal, natural principle of order through the use of lawful power, does not amount to external, unnatural coercion, and, therefore, does not invalidate the Acts due to its exercise.

Examples of councils working at high pressure, if the expression may be used, without spoiling their output, are of frequent occurrence. Most of the early councils were convened to execute decisions already finally fixed by the pope, no choice being left the assembled Fathers to arrive at another decision. They were forced to conform their judgment to that of Rome, with or without discussion. Should papal pressure go beyond the limits of the council’s dignity and of the importance of the matters under discussion, the effect would be, not the invalidation of the council’s decrees, but the paralyzing of its moral influence and practical usefulness. On the other hand, the fact that a synod is, or has been, acting under the leader-ship of its Divinely appointed head, is the best guarantee of its freedom from unnatural disturbances, such as intrigues from below or coercion from above. In the same way violent interference with the papal leadership is the grossest attack on the council’s natural freedom. Thus the Robber Synod of Ephesus (449), though intended to be general and at first duly authorized by the presence of papal legates, was declared invalid and null by those same legates at Chalcedon (451), because the prejudiced Emperor Theodosius II had removed the representatives of the pope, and entrusted the direction of the council to Dioscurus of Alexandria.

(c) Confirmation

Confirmation of the conciliar decrees is the third factor in the pope’s necessary cooperation with the council. The council does not represent the teaching Church till the visible head of the Church has given his approval, for, unapproved, it is but a headless, soulless, impersonal body, unable to give its decisions the binding force of laws for the whole Church, or the finality of judicial sentences. With the papal approval, on the contrary, the council’s pronouncements represent the fullest effort of the teaching and ruling Church, a judicium plenissimum, beyond which no power can go. Confirmation being the final touch of perfection, the seal of authority, and the very life of conciliar decrees, it is necessary that it should be a personal act of the highest authority, for the highest authority cannot be delegated. So much for the principle, or the question of right. When we look for its practical working throughout the history of councils, we find great diversity in the way it has been applied under the influence of varying circumstances.

Councils over which the pope presides in person require no further formal confirmation on his part, for their decisions formally include his own as the body includes the soul. The Vatican Council of 1869-70 offers an example in point.

Councils over which the pope presides through his legates are not identified with himself in the same degree as the former. They constitute separate, dependent, representative tribunals, whose findings only become final through ratification by the authority for which they act. Such is the theory. In practice, however, the papal confirmation is, or may be, presumed in the following cases:

(a) When the council is convened for the express purpose of carrying out a papal decision previously arrived at, as was the case with most of the early synods; or when the legates give their consent in virtue of a special public instruction emanating from the pope; in these circumstances the papal ratification pre-exists, is implied in the conciliar decision, and need not be formally renewed after the council. It may however, be superadded ad abundantiam, as, e.g. the confirmation of the Council of Chalcedon by Leo I.

The necessary consent of the Apostolic See may holding, also reverently receives: therefore we also, also be presumed when, as generally at the Council of and through our office this Apostolic See, consent to, Trent, the legates have personal instructions from the pope on each particular question coming up for decision, and act conformably, i.e. if they allow no decision to be taken unless the pope’s consent has previously been obtained.

Supposing a council actually composed of the greater part of the episcopate, concurring freely in a unanimous decision and thus bearing unexceptional the witness to the mind and sense of the whole Church: The pope, whose office it is to voice infallibly the mind of the Church, would be obliged by the very nature of his office, to adopt the council’s decision, and consequently his confirmation, ratification, or approbation could be presumed, and a formal expression of it dispensed with. But even then his approbation, presumed or expressed, is juridically the constituent factor of the decision’s perfection.

(3) The express ratification in due form is at all times, when not absolutely necessary, at least desirable and useful in many respects:—

It gives the conciliar proceedings their natural and lawful complement, the keystone which closes and crowns the arch for strength and beauty; it brings to the front the majesty and significance of the supreme head of the Church.

Presumed consent can but rarely apply with the same efficacy to each and all of the decisions of an important council. A solemn papal ratification puts them all on the same level and removes all possible doubt.

Lastly the papal ratification formally promulgates the sentence of the council as an article of faith to be known and accepted by all the faithful; it brings to light and public view the intrinsic ecumenicity of the council; it is the natural, official, indisputable criterion, or test, of the perfect legality of the conciliar transactions or conclusions. If we bear in mind the numerous disturbing elements at work in and around an ecumenical council, the conflicting religious, political, scientific, and personal interests contending for supremacy, or at least eager to secure some advantage, we can easily realize the necessity of a papal ratification to crush the endless chicanery which otherwise would endanger the success and efficacy of the highest tribunal of the Church. Even they who refuse to see in the papal confirmation an authentic testimony and sentence, declaring infallibly ecumenicity of the council and its decrees to be dogmatic fact, must admit that it is a sanative act and supplies possible defects and shortcomings; the situation of the Apostolic See issued in support of the ecumenical authority of the pope is sufficient to impart validity and infallibility to the decrees he makes by officially ratifying them. This was done by Pope Vigilius for the Fifth General Synod. Sufficient proof for the sanatory efficacy of the papal ratification lies in the absolute sovereignty of the pope and in the infallibility of his ex-cathedra pronouncements. Should it be argued, however, that the sentence of an ecumenical council is the only absolute, final, and infallible sentence, even then, and then more than ever, the papal ratification would be necessary. For in the transactions of an ecumenical council the pope plays the principal part, and if any of deficiency in his action, especially in the exercise of his own special prerogatives, were apparent, the labors of the council would being vain. The faithful hesitate to accept as infallible guides of their faith documents authenticated by the seal of the fisherman, or the Apostolic See, which now wields the authority of St. Peter and of Christ. Leo II beautifully expresses these ideas in his ratification of the Sixth General Council: “Because this great and universal synod has most fully proclaimed the definition of the right faith, which the Apostolic See of St. Peter the Apostle, whose office we, though unequal to it, are holding, also reverently receives: Therefore we also, and through our office this Apostolic See, consent to, and confirm, by the authority of Blessed Peter, those things which have been defined, as being finally set by the Lord Himself on the solid rock which is Christ.”

No event in the history of the Church better illustrates the necessity and the importance of papal cooperation and, in particular, confirmation, that the controversies which in the sixth century raged about the Three Chapters. The Three Chapters were the condemnation of Theodore of Mopsuestia, his person, and his writings: of Theodoret‘s writings against Cyril and the Council of Ephesus; of a letter from Ibas to Maris the Persian, also against Cyril and the Council. Theodore anticipated the heresy of Nestorius; Ibas and Theodoret were indeed restored at Chalcedon, but only after they had given orthodox explanations and shown that they were free from Nestorianism. The two points in debate were: (I) Did the Council of Chalcedon acknowledge the orthodoxy of the said Three Chapters? (2) How, i.e. by what test, is the point to be settled? Now the two contending parties agreed in the principle of the test: the approbation of the council stands or falls with the approbation of the pope’s legates and of Pope Leo I himself. Defenders of the Chapters, e.g. Ferrandus the Deacon and Facundus of Hermiane, put forward as their chief argument the fact that Leo had approved. Their opponents never questioned the principle but denied the alleged fact, basing their denial on Leo’s epistle to Maximus of Antioch in which they read: “Si quid sane ab his fratribus quos ad S. Synodum vice me, praeter id quod ad causam fidei pertinibat gestum fuerit, nullius erit firmitatis” (If indeed anything not pertaining to the cause of faith should have been settled by the brethren I sent to the Holy synod to hold my place, it shall be of no force). The point of doctrine referred to is the heresy of Eutyches; the Three Chapters refer to that Nestorius, or rather to certain persons and writings connected with it.

The bishops of the council, assembled at Constantinople in 533 for the purpose of putting an end to the Three Chapters controversy, addressed to Pope Vigilius two Confessions, the first with the Patriarch Mennas, the second with his successor Eutychius, in which, to establish their orthodoxy, they profess that they firmly hold to the four general synods as approved by the Apostolic See and by the popes. Thus we read in the Confessio of Mennas: “But also the letters Pope Leo of blessed memory and the Constitution of the Apostolic See issued in support of the Faith and of the authority of the aforesaid four synods, we promise to follow and observe in all points and we anathematize any man, who on any occasion or altercation should attempt to nullify our promises.” And in the Confessio of Eutychius: “Suscipiamus autem et ampectimur epistols praesulum Romanae Sedis Apostlicae, tam aliorum quam Lenis sanctae memoriae de fide scirpitas et de quattuor sanctis concilis vel de uno eorum ” (We receive and embrace the letters of the bishops of the Apostolic Roman See, those of others as well as of Leo of holy memory, concerning the Faith and the four holy synods or any of them).

VII. BUSINESS METHODS

The way in which councils transact business now demands our attention. Here as in most things, there is an ideal which is never completely realized in practice.

(a) The facts

It has been sufficiently shown in the foregoing section that the pope, either in person or by deputy, directed the transaction of conciliar business. But when we look for a fixed order or set of rules regulating the proceedings we have to come down to the

Vatican Council to find an official Ordo concilii oecumenic and a Methodus servanda in prima sessione, etc. In all earlier councils the management of affairs was left to the Fathers and adjusted by them to the particular objects and circumstances of the council. The so-called Ordo celebrandi Concilii Tridentine is a compilation posterior to the council, written by the conciliar secretary, A. Massarelli; it is a record of what has been done, not a rule of what should be done. Some fixed rules were, however, already established at the reform councils of the fifteenth century as a substitute for the absent directing power of the pope. The substance of these rulings is given in the “Cremoniale Romanum” of Augustinus Patritius (d. 1496). The institution of “congregations” dates from the Council of Constance (1415). At earlier councils all the meetings of the Fathers were called indiscriminately sessiones or actions, but since Constance the term session has been restricted to the solemn meetings at which the final votes are given, while all meetings for the purpose of consultation or provisory voting are termed congregations.

The distinction between general and particular congregations likewise dates from Constance, where, however, the particular congregations assumed a form different in spirit and composition from the practice of earlier and later councils. They were simply separate assemblies of the “nations” (first four, then five) present at the council; their deliberations went to form national votes which were presented in the general assembly, whose decisions conformed to a majority of such votes. The particular congregations of more recent councils were merely consultative assemblies (committees, commissions) brought together by appointment or invitation in order to deliberate on special matters. At Trent there were congregations of prelates and congregations of theologians, both partly for dogma, partly for discipline. The congregations of prelates were either “deputations”, i.e. committees of specially chosen experts, or conciliary groups, usually three, into which the council divided for the purpose of facilitating discussion.

The official ordo of the Vatican Council confirmed the Tridentine practice, leaving, however, to the initiative of the prelates the formation of groups of a more private character. The voting by “nations”, peculiar to the reform councils, has also been abandoned in favor of the traditional voting by individuals (capita). At the Vatican Council there were seven “commissions” consisting of theologians from all countries, appointed a year before the actual meeting of the assembly. Their duty was to prepare the various matters to be laid before the council. The object of these congregations is sufficiently described by their titles: (I) Congregatio cardinalitia directrix; (2) Commissio caeremoniarum; (3) politicoecclesiastica; (4) pro ecclesiis et missionibus Orientis; (5) pro Regularibus; (6) theologica dogmatica; (7) pro discipline ecclesiastics (i.e. a general directive cardinalitial congregation, and several commissions for ceremonies, politico-ecclesiastical affairs, the churches and missions of the Orient, the regular orders, dogmatic theology, ecclesiastical discipline). On the basis of their labors were worked out the schemata (drafts of decrees) to be discussed by the council. Within the council itself there were seven “deputations”: (I) Pro recipiendis et expendendis Patrum propositionibus (appointed by the pope to examine the propositions of the Fathers); (2) Judices excusationum (Judges of excuses); (3) Judices querelarum et controversiarum (to settle questions of precedence and such like); (4) deputatio pro rebus ad fidem pertinentibus (on matters pertaining to faith); (5) deputatio pro rebus disciplines ecclesiasticae (on ecclesiastical discipline); (6) pro rebus ordinum regularium (on religious orders); (7) pro rebus ritus orientalis et apostolicis missionibus (Oriental rites and Apostolic missions).

All these deputations, except the first, were chosen by the council. Objections and amendments to the proposed schemata had to be handed in writing to the responsible deputation which considered the matter and modified the schema accordingly. Anyone desiring further to improve the modified draft had to obtain from the legates permission to propose his amendments in a speech, after which he put them down in writing. If, however, ten prelates decided that the matter had been sufficiently debated, leave for speaking was refused. At this stage the amendments were collected and examined by the synodal congregation, then again laid before the general congregation to be voted on severally. The votes for admission or rejection were expressed by the prelates standing or remaining seated. Next the schema, reformed in accordance with these votes, was submitted to a general congregation for approval or disapproval in toto. In case a majority of placets were given for it, it was accepted in a last solemn public session, after a final vote of placet or non placet (“it pleases”, or “it does not please”).

(b) The theory

The principle which directs the practical working of a council is the perfect, or best possible, realization of its object, viz. a final judgment on questions of faith and morals, invested with the authority and majesty of the whole teaching body of the Church. To this end some means are absolutely necessary, others are only desirable as adding perfection to the result. We deal first with these latter means, which may be called the ideal elements of the council:

(1) The presence of all the bishops of the world is an ideal not to be realized, but the presence of a very great majority is desirable for many reasons. A quasi-complete council has the advantage of being a real representation of the whole Church, while a sparsely attended one is only so in law, i.e. the few members present legally represent the many absent, but only represent their juridical power, their ordinary power not being representable. Thus for every bishop absent there is absent an authentic witness of the Faith as it is in his diocese. (2) A free and exhaustive discussion of all objections. (3) An appeal to the universal belief—if existing—witnessed to by all the bishops in council. This, if realized, would render all further discussion superfluous. (4) Unanimity in the final vote, the result either of the universal faith as testified to by the Fathers, or of conviction gained in the debates. It is evident that these four elements in the working of a council generally contribute to its ideal perfection, but it is not less evident that they are not essential to its substance, to its conciliary effectiveness. If they were necessary many acknowledged councils and decrees would lose their intrinsic authority, because one or other or all of these conditions were wanting. Again, there is no standard by which to determine whether or not the number of assisting bishops was sufficient and the debates have been exhaustive; nor do the Acts of the councils always inform us of the unanimity of the final decisions or of the way in which it was obtained. Were each and all of these four elements essential to an authoritative council no such council could have been held, in many cases, when it was none the less urgently required by the necessities of the Church. Authors who insist on the ideal perfection of councils only succeed in undermining their authority, which is, perhaps, the object they aim at. Their fundamental error is a false notion of the nature of councils. They conceive of the function of the council as a witnessing to, and teaching of, the generally accepted faith; whereas it is essentially a juridical function, the action of judges as well as of witnesses of the Faith. This leads us to consider the essential elements in conciliar action.

From the notion that the council is a court of judges the following inferences may be drawn: (I) The bishops, in giving their judgment, are directed only by their personal conviction of its rectitude; no previous consent of all the faithful or of the whole episcopate is required. In unity with their head they are one solid college of judges authoritatively constituted for united, decisive action—a body entirely different from a body of simple witnesses. (2) This being admitted, the assembled college assumes a representation of their colleagues who were called but failed to take their seats, provided the number of those actually present is not altogether inadequate for the matter in hand. Hence their resolutions are rightly said to rest on universal consent: universali consensu constituta, as the formula runs. (3) Further, on the same supposition, the college of judges is subject to the rule obtaining in all assemblies constituted for framing a judicial sentence or a common resolution, due regard being paid to the special relations, in the present instance, between the head and the members of the college: the cooperative verdict embodies the opinion of the majority, including the head, and in law stands for the verdict of the whole assembly; it is communi sensu constitutum (established by common consent). A majority verdict, even headed by papal legates, if disconnected from the personal action of the pope, still falls short of a perfect, authoritative pronouncement of the whole Church, and cannot claim infallibility. Were the verdict unanimous, it would still be imperfect and fallible, if it did not receive the papal approbation. The verdict of a majority, therefore, not endorsed by the pope, has no binding force on either the dissentient members present or the absent members, nor is the pope bound in any way to endorse it. Its only value is that it justifies the pope, in case he approves it, to say that he confirms the decision of a council, or gives his own decision sacro approbante concilio (with the consent of the council). This he could not say if he annulled a decision taken by a majority including his legates, or if he gave a casting vote between two equal parties. A unanimous conciliary decision, as distinct from a simple majority decision, may under certain circumstances, be, in a way, binding on the pope and compel his approbation—by the compelling power, not of a superior authority, but of the Catholic truth shining forth in the witnessing of the whole Church. To exert such power the council’s decision must be clearly and unmistakably the reflex of the faith of all the absent bishops and of the faithful.

To gain an adequate conception of the council at work it should be viewed under its twofold aspect of judging and witnessing. In relation to the faithful the conciliar assembly is primarily a judge who pronounces a verdict conjointly with the pope, and, at the same time, acts more or less as witness in the case. Its position is similar to that of St. Paul towards the first Christians: quod accepistis a me per multos testes. In relation to the pope the council is but an assembly of authentic witnesses and competent counselors whose influence on the papal sentence is that of the mass of evidence which they represent or of the preparatory judgment which they pronounce; it is the only way in which numbers of judges can influence one another. Such influence lessens neither the dignity nor the efficiency of any of the judges; on the other hand it is never required, in councils or elsewhere, to make their verdict unassailable. The Vatican Council, not excluding the fourth session in which papal infallibility was defined, comes nearer than any former council to the ideal perfection just described.

It was composed of the greatest number of bishops, both absolutely and in proportion to the totality of bishops in the Church; it allowed and exercised the right of discussion to an extent perhaps never witnessed before; it appealed to a general tradition, present and past, containing the effective principle of the doctrine under discussion, viz. the duty of submitting in obedience to the Holy See and of conforming to its teaching; lastly it gave its final definition with absolute unanimity, and secured the greatest majority—nine-tenths—for its preparatory judgment.

VIII. INFALLIBILITY OF GENERAL COUNCILS

All the arguments which go to prove the infallibility of the Church apply with their fullest force to the infallible authority of general councils in union with the pope. For conciliary decisions are the ripe fruit of the total life-energy of the teaching Church actuated and directed by the Holy Ghost. Such was the mind of the Apostles when, at the Council of Jerusalem (Acts, xv, 28), they put the seal of supreme authority on their decisions in attributing them to the joint action of the Spirit of God and of themselves: Visum est Spiritui sancto et nobis (It hath seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to us). This formula and the dogma it enshrines stand out brightly in the deposit of faith and have been carefully guarded throughout the many storms raised in councils by the play of the human element. From the earliest times they who rejected the decisions of councils were themselves rejected by the Church. Emperor Constantine saw in the decrees of Nicaea “a Divine commandment” and Athanasius wrote to the bishops of Africa: “What God has spoken through the Council of Nicaea endureth for ever.” St. Ambrose (Ep. xxi) pronounces himself ready to die by the sword rather than give up the Nicene decrees, and Pope Leo the Great expressly declares that “whoso resists the Councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon cannot be numbered among Catholics” (Ep. lxxviii, ad Leonem Augustum). In the same epistle he says that the decrees of Chalcedon were framed instruente Spiritu Sancto, i.e. under the guidance of the Holy Ghost. How the same doctrine was embodied in many professions of faith may be seen in Denzinger’s (ed. Stahl) “Enchiridion symbolorum et definitionum”, under the heading (index) “Concilium generale representat ecclesiam universalem, eique absolute obediendum” (General councils represent the universal Church and demand absolute obedience). The Scripture texts on which this unshaken belief is based are, among others: “But when he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will teach you all truth …” (John, xvi, 13); “Behold I am with you [teaching] all days, even to the consummation of the world” (Matt., xxviii, 20); “The gates of hell shall not prevail against it [i.e. the Church]” (Matt., xvi, 18).

IX. PAPAL AND CONCILIAR INFALLIBILITY