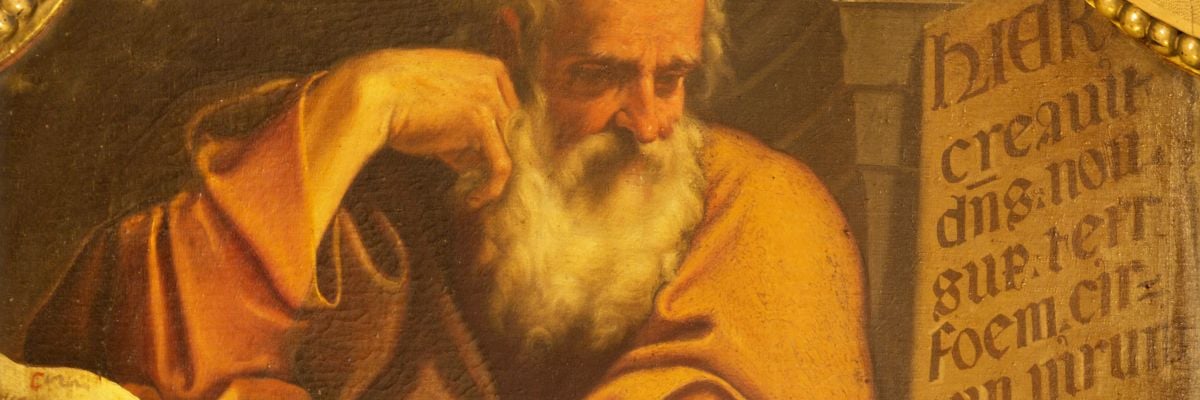

Jeremiah is the second of the four great prophets of Israel, a contemporary of Zephaniah, Nahum, and Habakkuk. He was born in the last part of the reign of Manasseh (687-642), around the year 645 B.C., almost a century after Isaiah. He came from a priestly family in Anathoth, a town about five kilometers northeast of Jerusalem.

God called him in the thirteenth year of Josiah’s reign (626), when he was still an adolescent (1:2). By express order of Yahweh he remained unmarried (16:2), embracing celibacy with generosity. A rather shy and extremely sensitive person, Jeremiah’s own preference was for a quiet family life and small-town friendships (6:11, 9:20). God’s call came to him at a time when the kingdom of Judah was about to collapse. He realized he could not contain the sentiments God had placed in his heart: “There is in my heart as it were a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot” (20:9).

For more than forty years, up to his death, he remained faithful to his vocation and prophesied until after the fall of Jerusalem in 587. Although his writings do not compare in quality and doctrinal depth with Isaiah, they overflow with spontaneity and simplicity and a most touching love for his people.

Jeremiah lived in a very eventful period, the reigns of the last five kings of Judah. His book refers a few times to Josiah (638-609), Jehoahaz (609) and Jehoiachin (598), but it mainly has to do with the reigns of the proud and skeptical Jehoiakim (608-598) and of the weak-willed Zedekiah (598-587).

As we will remember from 1 and 2 Kings, Josiah, in his efforts to rebuild national unity, opposed Pharaoh Neco III when he was trying to deal with the coalition of Medes and Babylonians. He went out to meet him at Megiddo and was slain. His son Jehoahaz was proclaimed king by the people, but after ruling for three months he was taken prisoner and brought to Egypt. In his place Neco imposed Jehoiakim, Josiah’s second son, as king; he was a proud, superstitious, and cruel man. Jeremiah upbraided him for his servility toward the Egyptians, saying that it would cause his downfall and ruin the country. Jeremiah had not favored pacts against the Medes; he had prophesied that the Chaldeans would prevail and that Jerusalem would be destroyed (20:1-3, 26:7-24).

Four years later, as a result of the battle of Carchemish (605 B.C.), all Syria and Palestine came under the control of the new Babylonian empire, and Egypt had been forced back to the narrow limits of its traditional frontiers.

Although he was Nebuchadnezzar’s vassal, Jehoiakim continued his own policy of alliance with the Egyptians. Hence his open opposition to Jeremiah, who wanted the king to cooperate with the Chaldeans because he knew that the Babylonian empire was the instrument God planned to use to punish Israel for its unfaithfulness. When Jehoiakim very stupidly refused to pay tribute to Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar himself intervened, in 598, and declared war on Judah.

On his death (possibly by assassination) Jehoiakim was succeeded by his son Jehoiachin, who three months later gave himself up to the Chaldeans when they began to besiege Jerusalem; he was deported to Babylon, and with him the queen mother, the entire court, and many nobles and people of every class except the poorest. Jeremiah was among these exiles (597).

Nebuchadnezzar made Judas Mattaniah, Jehoiachin’s uncle, king in his place; he changed his name to Zedekiah. Amazingly, he followed the same policy as his nephew despite all Jeremiah’s efforts to bring him to his senses. After attempting to form a coalition in 593 (51:59-64), Zedekiah eventually did rebel against the Chaldeans in 588, with the support of the new Egyptian pharaoh, Hophra. Nebuchadnezzar established his base at Riblah and launched a huge offensive against Jerusalem, the center of the rebel coalition (Ezek. 21:23-27). After a severe eighteen-month siege Hophra was defeated and fled, leaving Judah to its fate (Jer. 7:3-10). Finally, in July-August 587, Nebuchadnezzar took the city, sacked it, and burned it.

The Chaldeans appointed Gedaliah, a man who enjoyed the emperor’s trust, to govern the few who were left. He set about the task of building up the morale of his countrymen, a task in which Jeremiah supported him (ch. 40). Gedaliah’s efforts were soon brought to an end because a group of fanatics, led by Ishmael and open enemies of Babylon, treacherously killed him. Jeremiah and Baruch (43:6) were forcibly taken to Egypt when the remaining Israelites fled there.

In Egypt, in the city of Tahpanhes, Jeremiah contrived to prophesy against idolatrous Jews; he probably died there soon after, stoned by those same men, who could not stomach his criticism.

In the fifty-two chapters of this book oracles alternate with passages of history which confirm and illustrate the prophecies. The book as we have it does not follow a chronological or other order because it is, as Jerome described, more a collection of writings than a book in the proper sense. These writings consist of a series of warnings and threats of divine retribution for the unfaithfulness of the Chosen People and also for the behavior of neighboring peoples.

The book, which both Jews and Christians regard as proto-canonical, begins with a prologue (chap. 1), which gives an account of Jeremiah’s vocation, and it ends with an epilogue (chap. 52), which is a kind of historical summary of the whole collection. The rest of the book has three main parts: (a) the reprobation and condemnation of the Jewish people (2-19); (b) the execution of God’s sentence against them (20-45); (c) prophecies against foreign nations (46-51).

It is very probable that in its present form the book is the result of a recopilation of oracles dictated by Jeremiah to Baruch in 605, oracles which go back to the year 626, when he began his ministry. The content of the first scroll, which was burned in a fit of anger by King Jehoiakim, was re-dictated by the prophet and expanded by him (36:32). Some of the additions which can be identified in the text date from after 605 and were probably begun by Jeremiah and later edited by Baruch, probably after the fall of Jerusalem in 587.

Although this book is not essentially a didactic work, we can learn a lot from it. It shows us the drama of the interior life of a man whom God chose to be his spokesman—his prophet—to a people who persisted in their unfaithfulness to the Covenant of Sinai. Jeremiah, who is a man of peace and seeks the good of his people, has to preach the word of God tirelessly, often uttering threats and predicting wars.

In spite of his natural shyness God chose him “over nations and over kingdoms, to pluck up and to break down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant” (1:10). He is changed, very much against his own inclinations, into “a man of strife and contention to the whole land” (15:10) through his fidelity to his prophetic calling.

Jeremiah finds it very difficult to understand why he has to suffer, why God is so slow in coming to his support. The greater his obedience to the task God has given him, the more he suffers. His life will remain forever as a symbol or sign of the route man must take to attain happiness. In Jesus Christ light is at last shed on this mystery: “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matt. 16:24-25).

The source of Jeremiah’s faithfulness to God is his elevated concept of God, which is very similar to that found in Isaiah. The book vigorously asserts that there is only one God, and it rejects idolatry and religious syncretism. Its oracles against the nations, for example, proclaim God’s omnipotence: He is the creator and provider not only of Israel but of the whole world. Yet Jeremiah takes pleasure in recalling the early faithfulness of the Chosen People, describing it as the idyllic period of the betrothal (2:2; 3:4) of Yahweh and Israel. This is the same kind of language as the prophet Hosea uses, and it echoes the Song of Songs, where the love between Yahweh and Israel is compared with the love of husband and wife.

The New Covenant of which Jeremiah speaks is something which will come with the Messiah, and it will be like a return to the fidelity and intimacy of the early times. Israel will again become the first-born son of God, and Yahweh will be the tenderest of parents (31:9), but the new Israel will grow only out of the “remnant” of the people which has stayed true (3:14). Against this background of God’s infinite love and tenderness, Jeremiah denounces sins of lust, injustice, dishonesty, false oaths, hypocrisy. He sees sin as a grave rebellion against God which requires the sinner’s “returning” humbly and sincerely to the fountain of living waters (3:7-14, 22, 4:1).

In this context it is easier to understand the energy with which he proclaims the need for a religion of the heart, in “spirit and truth” (John 4:23) as opposed to the empty formalism of worship not based on sincerity of heart (7:21ff). But it would be a mistake to think that this means that he does not appreciate ritual, external worship: His whole point is that it must be rooted in genuine interior worship (17:26, 33:18).

Jeremiah’s insistence on the need to develop deep religious feelings is based on his appreciation of the value and power of prayer. He has recourse to prayer when he sees the danger that threatens his nation (7:16, 11:14); he begs men to join him in extolling divine justice (12:1-5) which punishes the evil doer. He asks God to come to his own aid (18:19) because he realizes he can do nothing without God’s favor. He gratefully acknowledges and teaches others that humble, trusting prayer is always effective (27:18, 37:3). In view of all this it is correct to say that Jeremiah’s life was not a failure, as some people superficially make out. On the contrary, his whole life is a wonderful lesson on the close terms on which a person like him can be with God, despite contradictions, sufferings, and misunderstanding. That was simply the route God wanted him to take in order to carry out his important mission. Indeed, his experiences make him a figure of Jesus Christ and a precursor of the New and definitive Covenant.