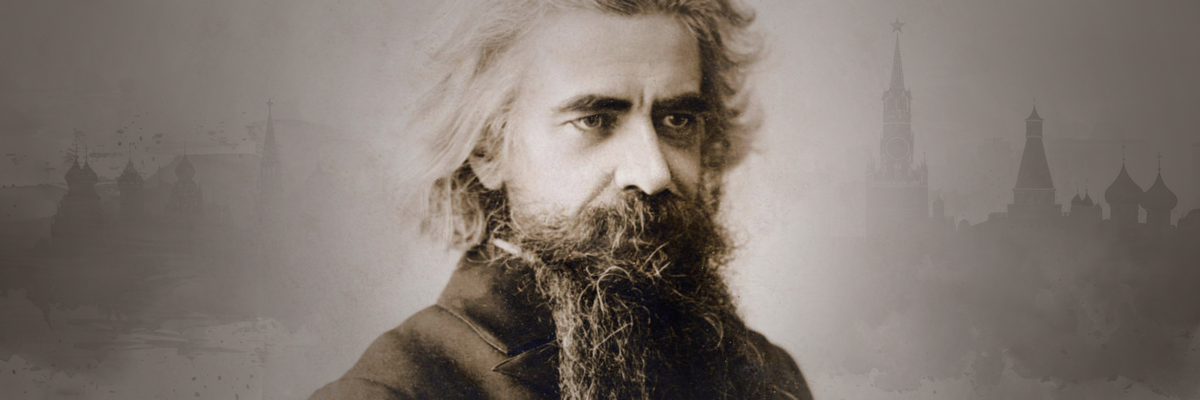

Once upon a time there lived a giant in Russia. Unlike other giants we read about in fairy tales, this giant was real; he lived from 1853 to 1900. He was an unusual kind of giant. We call him an ecumenical giant because he stood head and shoulders above his contemporaries in his understanding of Christian disunity, especially with regard to the split between the Eastern churches and Rome. Yet this giant is largely unknown today. His name: Vladimir Soloviev (variously transliterated as “Solovyov” or “Solovyev”).

Who was this giant? He was a genius with a broad range of intellectual and spiritual gifts. Biographers credit him with being philosopher, political thinker, theologian, literary critic, poet, prophet, mystic.

What is the stature of this giant? One who has taken his measure is the eminent Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar. In a long essay he pays highest tribute to Soloviev. “Soloviev’s skill in the technique of integrating all partial truths in one vision makes him perhaps second to Thomas Aquinas as the greatest artist of order and organization in the history of thought.” Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics. Vol. 3: Studies in Theological Styles: Lay Styles (San Francisco, 1986), 284.

With regard to Soloviev’s efforts to reconcile the Eastern Churches to Rome, von Balthasar praises Soloviev’s “brilliant apologia” for “its clarity, verve and subtlety,” and declares that “it belongs amongst the masterpieces of ecclesiology.” Ibid., 334.

In a standard history of the ecumenical movement, a distinguished Eastern theologian, Georges Florovsky, has praised Soloviev for his passion for Christian unity. Soloviev regarded the reunion of Christendom, and especially the reconciliation between the Eastern churches and Rome, as “the central problem of Christian life and history.” Florovsky calls Soloviev’s contribution to the discussion on Christian unity “momentous.” Georges Florovsky, “The Orthodox Churches and the Ecumenical Movement Prior to 1910” (Ruth Rouse and Stephen Neill, eds., A History of the Ecumenical Movement, 1517-1948 [Philadephia, 1967]), 214.

It was only during the last two decades of his brilliant career that Soloviev focused his attention on Christian unity. His primary concern was the reunion of the Russian Church and the Catholic Church. In 1886 he submitted to Croatian Archbishop Strossmayer a proposal for reuniting the two churches. The archbishop was deeply impressed. He commended Soloviev to the papal nuncio in Vienna and arranged for an audience with Pope Leo XIII. At that audience in the spring of 1888 the pope gave Soloviev the papal benediction in recognition of his efforts at reuniting the Russian and Catholic Churches Peter P. Zouboff, Vladimir Solovyev’s Lectures on Godmanhood (International University Press, 1944), 31.

Solovyev made several trips to Europe to confer with representatives of the Uniate churches and with Jesuit theologians. By 1886 his reunion activities were widely recognized and, in official circles, greatly deplored. Both the Russian Church and the Russian imperial government banned him from all public activities. They said his work was harmful to the Russian imperial regime and to the [Orthodox] Church of Russia.

At this point Soloviev seriously considered entering a Russian monastery. He decided against it because the monastic authorities would not allow him to continue his pro-Catholic activities. At the request of a French Jesuit, Soloviev wrote in French a summary of his ideas, Russia and the Universal Church, published in 1889.

Which was Soloviev’s church? Was he “Orthodox”? Was he Catholic? The data we have are confusing. Soloviev was raised in the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1896 he made a profession of faith in the Catholic Church before an Eastern-rite priest. That priest received him into the Church and gave him Communion. A year later Soloviev became ill and asked a Russian priest to give him Communion. Knowing that Soloviev had earlier been received into the Catholic Church, the priest refused.

Ten years after Soloviev’s death, a Russian priest wrote that he had heard Soloviev’s deathbed confession and had given him Communion. The priest also recounted some of the matter of Soloviev’s confession, thereby breaking the seal of confession. That deplorable fact by itself, however, is not sufficient ground for ignoring or denying the Russian priest’s story.

So what is Soloviev’s ecclesiastical status? By his reception in 1896 he did enter the Catholic Church. Assume that he did, and by his own choice, receive last rites from an Eastern priest. Does this mean-as Easterners argue-that at death he was not Catholic, but a member of the Russian Orthodox Church? However one answers that question, one fact remains: Whatever Soloviev did on his deathbed, there is no evidence that he ever renounced his belief in the infallible teaching authority and the universal jurisdiction of the pope.

In his book, Russia and the Universal Church, Translated by Herbert Rees. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1948. Soloviev shows the operation of the teaching and jurisdictional authority of the pope in the early centuries of the Church. We turn now to paraphrase and quote some of the main themes of Soloviev’s book. Italics which appear have been added for emphasis.

The lengthy introduction to Russia and the Universal Church recounts the Eastern Church’s struggles with the great heresies from the time of Arius (fourth century) to the days of the Iconoclasts in the seventh century. Soloviev clearly brings out the one fact underlying the story of those tumultuous years. The fact is, the Eastern churches were repeatedly rescued from their homegrown heresies by the magisterial authority of the Chair of Peter. Yet except when the East needed a savior from its own heresies, most of the Eastern hierarchy and almost all emperors opposed, even attacked, the authority of Rome.

Some years after his conversion to the Catholic faith, Constantine moved the empire’s capital to Constantinople (the ancient city of Byzantium, the modern city of Istanbul). The attempt of Constantine and his successors to transform the Roman Empire into a Christian empire was largely a failure. The Byzantine empire was only nominally Christian. Its public morality, its institutions, its laws clearly reflected the old paganism. So did the life of its founder. Constantine himself did not hesitate to execute his eldest son and his wife for suspected offenses against harsh laws he had promulgated.

The contradiction between the Christian faith and the life of the empire cried out for resolution. Rather than break completely with the old paganism, the Byzantine Empire consistently sought to pervert the authentic faith. “This compromise between truth and error lies at the heart of all those heresies . . . which distracted Christendom from the fourth century to the ninth.” Some of those heresies were devised, and all of them were to some extent supported, by the imperial power.

The central truth of Christianity is the Incarnation, the perfect union of the human and the divine in Christ. The historical expression of that union is “Christian humanity, in which the divine is represented by the Church, centred in the supreme pontiff, and the human by the State.” In relationships between Church and state, the Church has primacy because the divine is superior to the human.

All of the heresies of the early centuries were attacks on the perfect unity of the human and divine in Christ. Their ultimate aim (not always consciously realized) was to undermine the bond between Church and state. They sought to establish the state’s independence of the Church and her truth. The Byzantine emperors were determined to uphold the absolutism of the pagan state within Christendom, and so they favored and even helped spread those heresies.

In their denial of the Incarnation the heretics maintained that Jesus Christ is not the true Son of God. They denied that he is of the same substance as the Father. They denied that God has become incarnate. They denied that mankind and nature have been united to the divine. Once they established their position, the pagan state would freely “keep its independence and supremacy intact.” This is why emperors after Constantine supported Arianism in the fourth century.

The essence of fifth-century Nestorianism is that Jesus Christ’s humanity is a person complete in itself. It is united to the Second Person of the Trinity only by a relationship. Using this assumption, the heretics and their imperial supporters could conclude that the human state is an entity complete in itself. It has only an external relation to the Christian faith, and is therefore independent of that faith. This reasoning led Emperor Theodosius actively to spread Nestorianism.

Monophysitism seems the exact opposite. This heresy held that the human nature of Jesus Christ has been completely absorbed into his divine nature. In fact, however, Monophysitism led to the same practical conclusion as Nestorianism. If Christ’s human nature has been absorbed into the divine, the Incarnation is an event in the past. The result: nature and humankind remain outside the realm of the divine. In other words, “Christ has borne away to heaven all that was His and has abandoned the earth to Caesar.”

The Emperor Theodosius seemed to do a theological flip-flop. He abandoned a defeated Nestorianism and adopted the new heresy of Monophysitism. He convened an ostensibly ecumenical council (Ephesus, 449) which adopted the heresy. (Pope Leo gave the council the name by which it is universally called: the “robber-council.”) The emperor evidently saw that both heresies, though apparently contradictory, had the same effect. Both denied the union of the divine and the human in Christ. By implication, both asserted the independence of the near-pagan state from the moral and spiritual direction of the Church.

The efforts of the Byzantine emperors to divorce the state from the Church were unrelenting. The “authority of a great Pope [Pope Leo the Great] had prevailed over that of a heretical council [the ‘robber-council’],” but the emperors, “more or less abetted by the Greek hierarchy, did not cease to attempt fresh compromises.”

The next major challenge to the Catholic faith was Monothelitism in the seventh century. Advocates of this heresy asserted that in the God-Man there was no human activity or will. His human will, they said, was completely controlled by his divine will. This heresy denied human freedom in Christ. It amounted to quietism or fatalism which would allow human nature no part in the working out of a person’s salvation. In this view, all a Christian can do is submit passively and completely to God and, by implication, to the state.

For over fifty years the Eastern emperors and the Eastern hierarchy upheld the heresy of Monothelitism. Almost the only exceptions among the clergy were a few monks loyal to the Catholic faith. They had to go to Rome to escape imperial and ecclesiastical persecution in the East. Eventually, at the Council of Constantinople in 680, Monothelitism was condemned.

The early heretics, then, had tried to separate from the divine-human unity the substance of man’s being (as in Nestorianism). They had tried to absorb humanity in the divine (in Monophysitism). They had sought to absorb the human will into the divine (in Monothelitism).

The last of the great heresies was Iconoclasm, the rejection of images in worship and in piety. Formally promulgated by Emperor Leo II in 726, this heresy denied to the material and sensible world any possibility of redemption and union with God. “Iconoclasm was more than a compromise; it was the suppression of Christianity.” In each of the previous heresies, under the appearance of a theological dispute there was a serious political and social issue. So, too, in Iconoclasm: beneath the surface of this ritual dispute lay a serious threat to the social life of Christendom.

In the sphere of worship, “the material realization of the Divine” is signified by relics and holy images. In the social sphere, the Incarnation is signified by an institution. “There is in the Christian Church a materially fixed point, an external and visible centre of action, an image and an instrument of the divine power. ” That image, that instrument, is the papacy.

“The apostolic see of Rome, that miraculous ikon of universal Christianity, was directly involved in the Iconoclastic struggle.” All the heresies basically were denials of the reality of the Incarnation, ” the permanence of which in the social and political order was represented by Rome. ”

The Chair of Peter always stood firm. All the early heresies, advocated or passively encouraged by the Eastern hierarchy, “encountered insuperable opposition from the Roman Church and finally came to grief on this Rock of the Gospel.”

The Iconoclastic heresy especially was a mortal enemy of the papacy. Its denial of the sacramentality of the material world was “a direct attack on the raison d’etre of the Chair of Peter as the real objective centre of the visible Church. ” To put it more bluntly, “The pseudo-Christian Empire of Byzantium was bound to engage in decisive combat with the orthodox Papacy; for the latter was not only the infallible guardian of Christian truth but also the first realization of that truth in the collective life of the human race.” As one reads the eloquent letters of Pope Gregory II to the barbarous Byzantine emperor, one realizes that “the very existence of Christianity was at stake.”

Because the papacy stood firm, truth prevailed. Iconoclasm was the last of the Eastern imperial heresies by which Constantine’s successors had tried to reconcile Christian truth with the paganism of the state. After the defeat of Iconclasm, the period of Byzantine “orthodoxy” began. Soloviev calls this period “a fresh phase of the anti-Christian spirit.” We can understand it only in the light of its origins during the struggle with the heresies we have enumerated.

In the five centuries from the days of Arius to those of the last of the Iconoclasts, there were three main parties in the empire and the Eastern churches. First were the formal heretics themselves. Their heresies were all supported by the imperial court at one time or another. Theologically “they represented the reaction of Eastern paganism to Christian truth.” Politically, they were implacable enemies of “that independent ecclesiastical government founded by Jesus Christ and represented by the apostolic see of Rome. ”

Being to some extent protégés of the court, the heretics readily conceded to the imperial power full authority not only in matters of state but also in matters of doctrine. At some point each of the heretics was abandoned by his sponsor. Every one turned for support to nations seeking freedom from the imperial yoke. Arians turned to the Goths and Lombards, who remained Arian for centuries. Nestorians turned to the Eastern Syrians. The Monophysites turned to the south and east and became the national religion of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Armenia.

The second party in the East was the zealously orthodox Catholic party which defended the faith against heretical compromises with paganism. Prominent in this party were Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Maximus the Confessor, Flavian. They also contended for ” the free and worldwide ecclesiastical government [the papacy] against the onslaughts of Caesaropapism and the aims of national separation.” (Caesaropapism is the attempt by a ruler completely to control the church within his realm, even its doctrine. This has always been a problem among the Eastern churches.)

This party included only a small number of the hierarchy but did have support of the great mass of the faithful and of the monks. (The latter were very influential in the Eastern churches in that era.) “These orthodox Catholics found and recognised in the central Chair of Peter the mighty palladium of religious truth and freedom.”

The third main party included a great majority of the Eastern hierarchy. Soloviev uses various terms to characterize them: “semi-orthodox,” “orthodox anti-Catholic,” “pseudo-orthodox.” In peaceful times members of this party held to orthodox teaching. “They had nothing in principle against the unity of the universal Church, provided only that the centre of that unity was situated in their midst.”

But because that center was located elsewhere, in Rome, in the papacy, “they preferred to be Greeks rather than Christians and accepted a divided Church rather than the Church unified by a power which was in their eyes foreign and hostile to their nationality.” In other words, they would rather accept from the emperor “a revised or incomplete formula” of doctrine, than ” accept the truth pure and intact from the mouth of a Pope.”

Throughout these centuries the orthodox anti-Catholic party exhibited a regular pattern of behavior. When a heresy was espoused by the emperor, they gave it at least passive support. This enabled the heretics to call councils (composed largely of orthodox anti-Catholic hierarchs) and issue heretical decrees. But each time the blood of martyrs and the loyalty of the faithful and “the threatening authority of the Roman pontiff” would compel the emperor to forsake the current heresy. At which point the orthodox anti-Catholic quickly rejoined the orthodox camp.

Thus the reconciled orthodox anti-Catholic constituted the majority in the legitimate councils as they had in the heretical councils. They could not refuse to concur in the ” precise and definite formulation of orthodox dogma which the pope’s representatives brought to their councils.” Yet each time “the evident triumph of the Papacy soon brought them back to their prevailing sentiment of jealous hatred toward the apostolic see.” They would begin again to set up “an unreal and usurped authority” opposedto the papacy.

When heresy reigned in the East, the orthodox anti-Catholic could turn only to the papacy to rescue them. Once the heresy was vanquished, however, they wanted nothing to do with the pope. Thus, “each triumph of orthodoxy, which was always the triumph of the Papacy, was invariably followed at Byzantium by an anti-Catholic reaction.” That reaction would persist until a new heresy arose, reminding them of “the advantage of a genuine ecclesiastical authority, ” the papacy, which would then rescue them.

[Though not noted by Soloviev, early chapters of the book of Judges reveal a similar pattern in the life of the ancient Hebrew people. Weakened by infidelity to their covenant with God, the people repeatedly fell victim to oppressors-usually the Philistines. They cried out for deliverance, and God summoned a leader to unite and rescue them from their enemies. Once free, they soon started the cycle again by lapsing into infidelity, being conquered, pleading for rescue.]

Repeatedly Soloviev stresses the decisive role played by the papacy in overcoming the major heresies of the fourth to ninth centuries. In 380 the Eastern hierarchy gathered and constituted themselves an ecumenical council “as though the whole of Western Christendom did not exist.” They replaced the Nicene statement of faith with a new formula. Though the bishop of Constantinople was then only a suffragan of the archbishop of Heraclea, the council gave him the title of first patriarch of the Eastern Church. This action ignored the rights of the apostolic sees of Alexandria and Antioch as confirmed by the council of Nicaea in 325.

Pope Damasus simply ignored the Easterners’ presumptive act regarding the bishop of Constantinople. But he did take action. Here Soloviev makes the point consistently ignored or even denied by Eastern apologists. Pope Damasus “approved the dogmatic act of the Greek council in his name and in that of the whole Latin Church and thereby gave it the authority of a true ecumenical council. ”

In the battle with the Christological heresies of the fifth century, the papacy’s role was even more dominant. Under pressure from the emperor, Eastern bishops (the orthodox anti-Catholic being the great majority) assembled at Ephesus in 449 and adopted an heretical profession of faith.

What did the pope do? “In contrast to this criminal weakness the Papacy appeared in all its moral power and majesty in the person of Leo the Great.” At the Council of Chalcedon in 451 the Eastern bishops “were obliged to beg forgiveness of the legates of Pope Leo, who was hailed as the divinely inspired head of the Universal Church. ”

Then came the usual orthodox anti-Catholic reaction. While still at Chalcedon some of them gathered in an irregular session. They decreed that the bishop of Constantinople, because his see was in the imperial city, should be regarded as equal to the pope and have jurisdiction over the whole Eastern Church. Then what happened? Note the irony: “This act, aimed against the sovereign Pontiff, had nevertheless to be humbly submitted by the Greeks for the ratification of the Pope himself, who quashed it completely.”

The Council of Chalcedon was ” an outstanding triumph for the Papacy. ” But “pure orthodoxy” was “too Roman” for the orthodox anti-Catholic. “They began to flirt with heresy.” Their leader Acacius, patriarch of Constantinople, accepted a heretical formula issued by the emperor who sought to compromise with the Monophysites. For this Acacius was excommunicated by the pope. Thus began the first formal schism between the West and the East.

Under pressure from the imperial government (which had reasons of its own), the successors of Acacius were gradually reconciled to the orthodox faith. The schism was ended ” to the advantage and honour of the Papacy. ” To prove their orthodoxy “and gain admission to the communion of the Roman Church,” the Eastern Bishops had to accept and sign a dogmatic formula issued by Pope Hormisdas. They thereby “recognise[d] implicitly the supreme doctrinal authority of the apostolic see. ”

But the Eastern prelates’ submission was not sincere. They continued to seek common ground with the Monophysites. And so ” the power of the Papacy was demonstrated afresh” when Pope Agapitus went to Constantinople. He deposed a patriarch of questionable orthodoxy. He installed in that see an orthodox patriarch. Finally, he “compelled all the Greek bishops to sign anew the formula of Hormisdas.”

In one short paragraph Soloviev uses several expressions which epitomize his understanding of the papacy. He speaks of the pope as ” the head of the Church” as ” sovereign Head of the government of the Church” as “the supreme Teacher of the Church.”

In the seventh century the emperor Heraclius espoused Monothelitism as a compromise between the authentic faith and Monophysitism. He thought his policy would bring peace, consolidate the Eastern churches, and set them free from Rome’s influence. He received strong support from the Eastern hierarchy. The patriarchal sees were occupied by heretics. For about fifty years Monothelitism was the official religion of the entire East. Led by Maximus the Confessor, a few monks who were champions of the orthodox faith fled to Rome for refuge. ” And once again the apostle Peter strengthened his brethren.”

Throughout the years of Monothelite ascendancy in the East, all the popes strenuously opposed the imperial heresy. One pope, Martin, “was dragged by soldiers from the altar, was haled like a criminal from Rome to Constantinople and from Constantinople to the Crimea, and finally gave his life for the orthodox faith.” At the end of the struggle between popes and emperors, “religious truth and moral power won the day.” Thus Soloviev sums up the victory: “The mighty Empire and its worldly clergy surrendered once again to a poor, defenceless pontiff.”

The sixth ecumenical council, Constantinople III (680), condemned Monothelitism. It paid honor to the apostolic see of Rome for having remained free from doctrinal error. Heretics and heresiarchs who had occupied the see of Constantinople were anathematized by the council. This was humiliating to the orthodox anti-Catholic.

True to form, they assembled again some years later in the imperial palace at Constantinople (hence the name “in Trullo”). They claimed ecumenical authority for this Eastern gathering “on various absurd pretexts.” They said it was the continuation of the sixth council. Alternatively, they argued it was the conclusion of the fifth and sixth councils (hence the name “Quinisext”). They condemned a number of ritual and disciplinary practices of the Catholic Church and thereby staked out grounds for schism from the West.

Schism did not occur at that time. The only reason was that about thirty years later the Iconoclast emperor, Leo the Isaurian, unleashed his compromise with authentic Catholic faith in the heresy of Iconoclasm. This was the most violent of the imperial heresies, and also the last.

As it had done repeatedly for centuries, the papacy again came to rescue the East from another of its heresies. The seventh ecumenical council in 787 condemned Iconoclasm. This council “had been assembled under the auspices of Pope Adrian I and had taken a dogmatic epistle of that pontiff as guide to its decisions. It was again a triumph for the Papacy. ”

Minor mopping-up operations in the East against remnants of the Iconoclast ranks were completed in 842. This event is celebrated in the East as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” It was a triumph made possible by the papacy’s intervention.

Now the centuries-old ideal of the orthodox anti-Catholic could be realized. With the imperial heresies finally at an end, the orthodox anti-Catholic had no further need for the pope. Thus, twenty-five years later the East separated itself from Rome in the schism of Photius (867), which was made official by Michael Cerularius in 1054.

The Byzantine emperors had always wanted to separate their dominions from Rome. All their doctrinal compromises between Christianity and paganism had been defeated by the papacy. Now they embarked on a new course. The Eastern churches were completely submissive to the imperial power. If the emperors stayed clear of heresy, they could reconcile “a strict theoretical orthodoxy” with “a political and social order which was completely pagan.”

And so for many centuries church and state in the East were bound by a “common idea: the denial of Christianity as a social force and as the motive principle of historical progress.” In other words, the emperors “permanently embraced ‘Orthodoxy’ as an abstract dogma, while the orthodox prelates bestowed their benediction in saecula saeculorum on the paganism of Byzantine public life.”

Soloviev explains his indictment this way. The central truth of Christianity is the Incarnation. The divine and the human have been brought into an “intimate and complete union” yet “without confusion or division.” In the realm of human existence, this truth logically requires that society and the state be evangelized and converted. According to Soloviev, this process of conversion never occurred in Byzantium. In Byzantine orthodoxy, the two elements, human and divine, were divided or confused, or one was suppressed or absorbed by the other.

A prime example was the Eastern attitude toward the emperor. In the confused minds of the Arians, Christ was a hybrid between man and God, neither fully human nor fully divine. In Eastern life, ” Caesaropapism, which was simply political Arianism, confused the temporal and spiritual powers without uniting them.” The emperor was regarded as something more than mere head of the state, but he was never seen as true head of the Church. In the minds and lives of Eastern Christians, religious society was compartmentalized and separated from secular society. The realm of religion was largely relegated to the monasteries. The public forum was given over to “pagan laws and passions.”

The result? “This so-called ‘orthodoxy’ of the Byzantines was in fact nothing but ingrown heresy.” At the heart of that “orthodoxy” was “a profound contradiction between professed orthodoxy and practical heresy.” That contradiction was “the Achilles’ heel of the Byzantine Empire.” It was the ultimate cause of the empire’s downfall.

The empire “deserved to fall.” Especially it deserved to fall before Islam. Why? Because Islam is “simply sincere and logical Byzantinism, free from all its inner contradictions.” Islam is in fact “the frank and full reaction of the spirit of the east against Christianity.”

The imperial heresies of the seventh and eighth centuries had prepared the way for the Moslem religion. The heresy of the Monothelites indirectly denied human freedom. Iconoclasm rejected the portrayal of the divine in any sensible form. These two errors constitute the essence of the religion of Islam, according to Soloviev.

The Moslem view “sees in man a finite form without freedom, and in God an infinite freedom without form.” God and man stand at opposite poles with no possibility of a filial relationship. Therefore in Moslem thought there is no possibility of the Incarnation or of persons becoming partakers of the divine nature. The Moslem religion posits “a mere external relation between the all-powerful Creator and the creature which is deprived of all freedom and owes its master nothing but a bare act of ‘blind surrender’ (for this is what the Arabic word Islam signifies).”

The Moslem religion has the advantage of simplicity. On the personal level, the act of surrender, repeated invariably each day at fixed hours, sums up “the religious background of the Eastern mind, which spoke its last word by the mouth of Mohammed.”

The Moslem perception of social and political concerns is equally simple. There is no real progress for the human race: “there is no moral regeneration for the individual and therefore a fortiori none for society; everything is brought down to the level of a purely natural existence.”

The only goal a Moslem society can have is to expand its material power and enjoy the good things of the earth. Its task is to spread Islam by force, if necessary, and to govern the faithful with absolute authority guided by the rules of justice set forth in the Koran. This, says Soloviev, is “a task which it would be difficult not to accomplish with success.”

Byzantinism in principle never seriously pursued Christian progress in social and political arenas. It relegated the affairs of the secular world entirely to the whims of the emperor. The Byzantine approach resulted in “reducing the whole of religion to a fact of past history, a dogmatic formula, and a liturgical ceremonial.” In fact, says Soloviev, Byzantinism was anti-Christian even though it wore “the mask of orthodoxy.” The whole enterprise “was bound to collapse in moral impotence before the open and sincere anti-Christianity of Islam.”

History has condemned the Byzantine empire. It failed to carry out its task of establishing a Christian state. The empire tried “to pervert orthodox dogma” and in fact “reduced it to a dead letter.” It attacked ” the central government of the Universal Church” and thereby “sought to undermine the edifice of the pax Christiana.”

Not surprisingly, according to Soloviev, under Moslem rule the religious life of the former Byzantine empire went on much as it had before the conquest. Byzantines interpreted Christianity in terms of “guarding the dogmas and sacred rites of orthodoxy without troubling to Christianise social and political life.” Indeed, “they thought it lawful and laudable to confine Christianity to the temple while they abandoned the marketplace to the principles of paganism.”

And so the Christians of the former Byzantine empire had no right to complain about their conquerors. Those conquerors gave them what they wanted. “Their dogma and their ritual were left to them; it was only the social and political power that fell into the hands of the Moslems, the rightful heirs of paganism.”

The calling to establish a Christian state, a calling rejected by the Byzantine empire, was handed over to the emerging tribes of the West. The transfer was made by ” the only Christian power that had the right and duty to do so, by the power of Peter, the holder of the keys of the Kingdom. ” Eventually the pope crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor.

This coronation was “the real and immediate cause of the separation of the [Western and Eastern] Churches.” It gave the Easterners even more reason for opposing the pope as an enemy and a foreigner.

Once the Byzantine emperors ceased fomenting heresies, in Constantinople there would be no support, because they felt no need, for the pope. And so the ” union of all the ‘Orthodox’ under the standard of anti-Catholicism would be complete.” The Eastern schism from Rome began under Patriarch Photius of Constantinople in the ninth century and finally became official under Patriarch Cerularius in the mid-eleventh century.

Soloviev makes a final indictment of the Byzantine empire in comparing it with the Franco-German empire in the West. Whatever its failures, the western empire had “one enormous advantage over the Byzantine Empire, namely the consciousness of its own evils and a profound desire to be rid of them.” Innumerable councils were convoked by emperors, kings and popes to bring about moral reforms in society and in the Church.

It is true that these attempts at reform never achieved their goals. Yet they did express “a refusal to accept in principle a contradiction between truth and life after the manner of the Byzantine world.” The Eastern empire “had never been concerned to harmonise its social conditions with its faith and had never undertaken any moral reformation.” The only concern of the Eastern councils had been “dogmatic formulae” and “the claims of its hierarchy.”

A fitting close to Soloviev’s analysis of the fatal weaknesses of the Byzantine empire is his statement of faith. Even while regarding himself as a member of the Russian Church, he submits himself fully to the authority of the successors of Peter.

“As a member of the true and venerable Eastern or Greco-Russian Orthodox Church which does not speak through an anti-canonical synod nor through the employees of the secular power, but through the utterance of her great Fathers and Doctors, I recognise as supreme judge in matters of religion him who has been recognised as such by Irenaeus, Dionysius the Great, Athanasius the Great, John Chrysostom, Cyril, Flavian, the Blessed Theodoret, Maximus the Confessor, Theodore of the Studium, Ignatius, etc., etc.-namely the Apostle Peter, who lives in his successors and who has not heard in vain our Lord’s words: ‘Thou art Peter and upon this rock I will build My Church’; ‘Strengthen thy brethren’; ‘Feed My sheep, feed My lambs.'”

Earlier we noted that Florovsky credits Soloviev with a “momentous” contribution to the discussion of Christian unity. Yet the tribute is strange. Florovsky gives no hint of Soloviev’s central thesis. He simply dismisses what he calls Soloviev’s “Romanism” and says it has nothing to do with the man’s “true legacy.” Florovsky, op. cit., 215. Florovsky is wrong about the legacy. As an unwilling beneficiary he can choose not share in it. But Soloviev’s “Romanism” is in fact Soloviev’s “true legacy.” It is the central thesis of Russia and the Universal Church, as even the title suggests.

What is that thesis? You can sum it up in three propositions. The universal jurisdiction and teaching authority of the papacy are divinely instituted. Apart from the papacy, the Eastern churches will remain simply ethnic, national churches. Only in union with Rome can the Eastern churches be truly “catholic.”