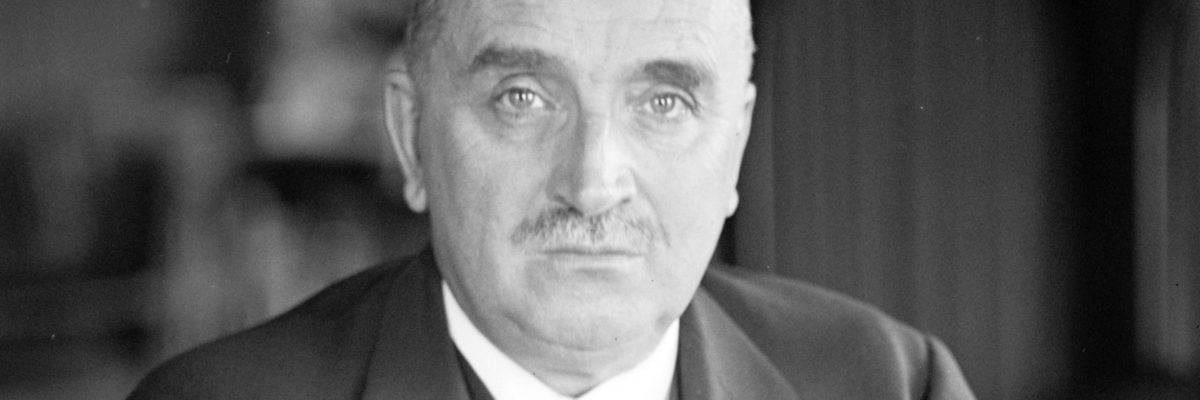

When I first read it, years ago, I thought that Louis Chaigne’s biography of Paul Claudel was the best-written biography I had ever come across. The book appeared in 1961, six years after Claudel’s death at the age of 86.

Paul Claudel: The Man and the Mystic covers the three men who were Claudel: the diplomat, the poet and playwright, and the Catholic. Chaigne writes lovingly and insightfully of the man who was his friend for thirty years. By the end of the book, I felt Claudel was my friend, too.

Then I misplaced the book. I had read it carefully, making my usual pencil notations in the margins, highlighting passages I wanted to return to again and again. As a sign of my delight in the book, I kept the slipcover. Normally I discard slipcovers, preferring my hardbacks to show their cloth spines on my shelves. But this slipcover I retained, out of respect for the author and his subject.

One day, after not having handled the book for many months, I looked for it but could find it nowhere. I must have run my fingers along my many bookshelves more than once, hoping I had misshelved it. But no, it was gone, and I couldn’t remember what I had done with it.

Years passed. At some point, I remember, I searched unsuccessfully for an affordable replacement copy. Used copies were available for upwards of a hundred dollars, but that was out of my reach. Then the whole matter faded into the recesses of my mind.

Last week I was visiting with one of our longtime staff apologists. As I sat in her office I glanced idly at her bookshelf, and what should catch my eye but Chaigne’s book—no, my book! It had been there all along. My memory became refreshed and I recollected how I had praised the biography to my colleague, who has a special fondness for French Catholic authors of the early twentieth century. I had loaned her the book. She put it on her shelf, intending to get to it, but she never did. The book slipped from her mind, too.

Now the book is back in my hands, a bit like the prodigal son who returned unexpectedly. I opened it to the page where Claudel’s conversion is recounted. When very young he fell away from the Faith but soon became dissatisfied with his life. He turned to Catholic books and read widely, coming much of the way to intellectual conviction but not spiritual conviction.

On Christmas Day in 1886 he attended High Mass at the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. He was not particularly moved by the ceremony, which probably was presided over by the newly appointed archbishop. Claudel left and then returned for vespers. “It was the gloomiest winter day and the darkest rainy afternoon over Paris,” he wrote. He listened to the psalms and the Magnificat.

For the rest of his life he recalled that he “stood near the second pillar at the entrance to the chancel, to the right, on the side of the sacristy.” There one finds a fourteenth-century statue of the Virgin and Child. “Then occurred the event which dominates my entire life,” he wrote.

“In an instant, my heart was touched and I believed. I believed with such a strength of adherence, with such an uplifting of my entire being, with such powerful conviction, with such a certainty leaving no room for any kind of doubt, that since then all the books, all the arguments, all the incidents and accidents of a busy life have been unable to shake my faith, nor indeed to affect it in any way.”

That same day, two hundred kilometers away in the small town of Lisieux, Therese Martin attended midnight Mass in the local cathedral. She wrote that on that Christmas Day she “received the grace of emerging from childhood, or in a word the grace of my full conversion.”

Chaigne writes that Claudel was “surprised” to learn, years later, of the future saint’s simultaneous conversion. That grace went to her at the same time it went to him must have given him consolation, much as I received consolation in having his biography come back to me.