The basic story of the beginning of the Protestant Reformation is well known to us—well, at least the popular telling of it. There may, of course, be elements of exaggeration and augmentation and outright fabrication, but the moral of the story is true: certain figures around Europe—especially Martin Luther, Jean Calvin, Jan Hus, and Ulrich Zwingli—were upset at what they thought were false teachings being espoused by the Catholic Church, and began teaching what they believed to be the truth in opposition to that.

This article is not the place to dive into all of the many problems with the teachings of these figures. The purpose of this article is to answer an intentionally scandalous question: Was Martin Luther right (and thus, the Catholic Church wrong) about indulgences?

Indulgences are widely misunderstood, as is the problem that Martin Luther had with them. So let’s take a closer look. First off:

What are indulgences?

An indulgence is “a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven, which the faithful Christian who is duly disposed gains under certain defined conditions through the Church’s help when, as a minister of redemption, she dispenses and applies with authority the treasury of the satisfactions won by Christ and the saints” (Indulgentiarum Doctrina 1). The Catechism of the Catholic Church elaborates that the Church has the authority to grant indulgences due to the power of binding and loosing granted to it by Jesus, and that this flows from an opening of the “treasury of merits of Christ and the saints” to obtain such remission “from the Father of mercies.”

So sin is real, and has real consequences, both temporal and eternal. The eternal punishment is remitted by confession of the sin, but the temporal consequences remain.

We see this in human interactions as well. If a child accidentally breaks the living room window, and he confesses to his parents, he will be forgiven—but the window remains broken, and the child must make restitution. The same principle applies here: We feel contrition, confess our sins, and reconcile ourselves to God, but we still must do penance and face the temporal consequences of our sins. An indulgence, through the merits of Christ and the saints, remits (in whole or in part) those temporal consequences.

There is scriptural basis for indulgences, which we find in the Jewish tradition of praying for the dead:

So they all blessed the ways of the Lord, the righteous Judge, who reveals the things that are hidden; and they turned to prayer, beseeching that the sin which had been committed might be wholly blotted out. And the noble Judas exhorted the people to keep themselves free from sin, for they had seen with their own eyes what had happened because of the sin of those who had fallen. He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand drachmas of silver, and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. In doing this he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection. For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Therefore he made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin (2 Macc. 12:41-46)

We also read about Jesus granting the power to forgive sins to the apostles and the Church: “If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained” (John 20:21-23). He also gave the power of binding and loosing, both in heaven and on earth: “Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matt. 18:18). The granting of indulgences—this remission of the temporal punishment due to sin—is a form of this binding and loosing.

The practice of granting indulgences can be found early in the Church’s history, so it had a very long patrimony by the time Martin Luther expressed his problems with it.

What was Martin Luther so upset about?

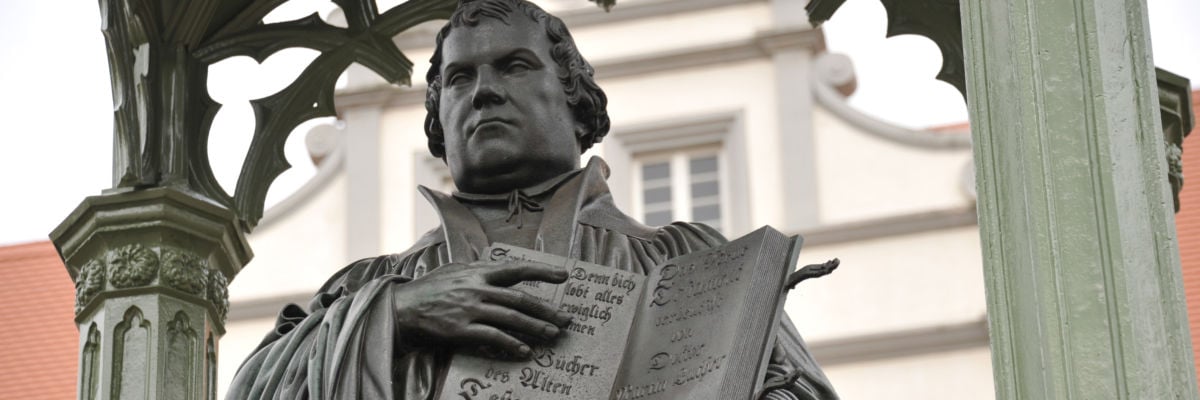

Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk in Wittenberg, Germany, who, in 1517, publicly identified a number of points of Catholic teaching he deemed problematic. One of his biggest issues was the Church’s teaching on indulgences and the fact that they were being sold.

In a letter dated October 31, 1517, he wrote,

I do not bring accusation against the outcries of the preachers, which I have not heard, so much as I grieve over the wholly false impressions that the people have conceived from them; to wit, the unhappy souls believe that if they have purchased letters of indulgence they are sure of their salvation; again, that so soon as they cast their contributions into the money-box, souls fly out of purgatory; furthermore, that these graces are so great that there is no sin too great to be absolved, even, as they say—though the thing is impossible—if one had violated the Mother of God; again, that a man is free, through these indulgences, from all penalty and guilt.

It is true that some individuals were taking advantage of Catholics’ misunderstanding of Church doctrine on this matter and collecting money in exchange for indulgences. Johann Tetzel was one of the most infamous offenders in this regard. But what we must remember is that there are really two issues here: first, the indulgence itself, and second, the sale of the indulgence. Luther had a problem with both.

So wasn’t he right about indulgences?

The Catholic Church has never condoned the sale of indulgences. As with so many other teachings of the Church, unfortunately, there were a number of individuals who acted in ways contrary to Church teaching. Tetzel and others who collected money in exchange for indulgences certainly committed a transgression, utterly opposed to the Church’s teaching on indulgences and her practices in that regard.

Even at the time (contrary to popular belief today), the Church spoke out against this abuse. For example, St. Cajetan (1469-1534) wrote, “Preachers act in the name of the Church so long as they teach the doctrines of Christ and the Church; but if they teach, guided by their own minds and arbitrariness of will, things of which they are ignorant, they cannot pass as representatives of the Church; it need not be wondered at that they go astray.” Similarly, the Council of Trent (1545-1563) issued a decree that read, in part,

Since the power of granting indulgences was conferred by Christ on the Church (cf. Mt 16:19, 18:18, Jn 20:23), and she has even in the earliest times made use of that power divinely given to her, the holy council teaches and commands that the use of indulgences, most salutary to the Christian people and approved by the authority of the holy councils, is to be retained in the Church, and it condemns with anathema those who assert that they are useless or deny that there is in the Church the power of granting them.

In granting them, however, it desires that in accordance with the ancient and approved custom in the Church moderation be observed, lest by too great facility ecclesiastical discipline be weakened. But desiring that the abuses which have become connected with them, and by any reason of which this excellent name of indulgences is blasphemed by the heretics, be amended and corrected, it ordains in a general way by the present decree that all evil traffic in them, which has been a most prolific source of abuses among the Christian people, be absolutely abolished. Other abuses, however, of this kind which have sprung from superstition, ignorance, irreverence, or from whatever other sources, since by reason of the manifold corruptions in places and provinces where they are committed, they cannot conveniently be prohibited individually, it commands all bishops diligently to make note of, each in his own church, and report them to the next provincial synod (Sess. 25, Decree on Indulgences).

So Martin Luther was right to rail against the sale of indulgences. And in doing so, he was perhaps unwittingly acting in tandem with the Church. He was protesting not the Catholic Church, but a bastardization of the Church’s teaching. However, whereas he was correct in protesting the sale of indulgences, he was misguided in his opposition to the indulgences themselves.