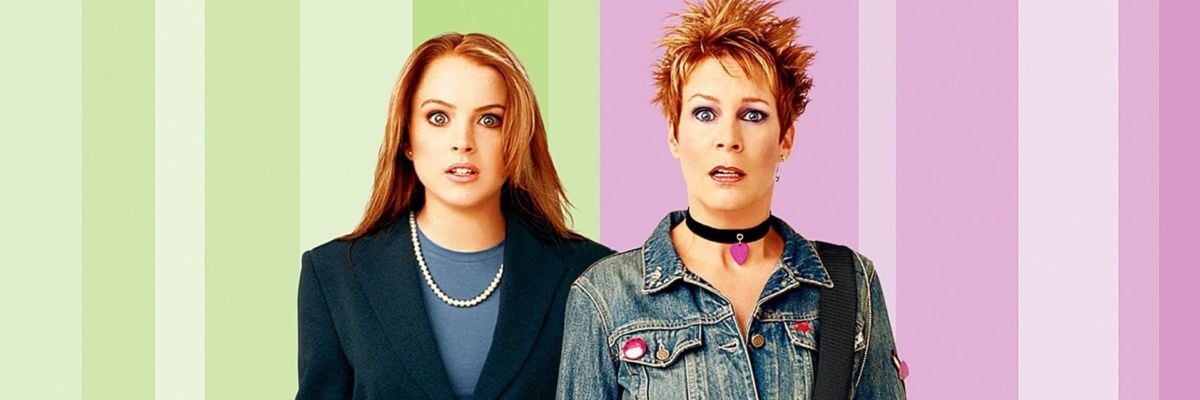

When I was a kid, I remember watching the movie Freaky Friday. It featured Lindsay Lohan as Anna, a teenage girl with an attitude, who wakes up one morning to find herself in her mom’s body and her mom in hers. Don’t stone me for blasphemy, but I am going to use this as a parallel to the Eucharist.

We have to intellectually wrestle with the fact that Jesus took bread into his hands at the Last Supper and called it his body. He said the blessing, broke the bread, and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take this all of you, and eat it, for this is my body, which will be given up for you.” He then took the Passover wine and said something similar. “Take this, all of you, and drink of it, for this is my blood.” What did Jesus mean when he spoke these words?

I’ll tell you what he didn’t mean. Jesus did not mean that this was just a symbol. That’s what many Protestants believe, not Catholics. Also, the Catholic Church has taught that Jesus is truly present in the Eucharist from the beginning.

Let me put it this way: when God tells us that bread is his body, we should believe him, even if we don’t understand how, because God himself said it was. Why should we believe that Jesus is God? Because he rose from the dead. It all comes down to the Resurrection. If Jesus is who he says he is, then it isn’t difficult to believe the miracles in the Gospels. And we know that Jesus is God because he told us he was, and he backed it up by rising from the dead.

So how does ordinary bread become the body of Christ? In order to understand this, we have to understand two terms that come from the philosopher Aristotle: a thing’s accidents versus its substance. To understand the difference between accidents and substance, I’ll return to our movie, Freaky Friday.

In the case of a daughter waking up and finding herself in her mom’s body, we see a change in that person’s substance. The core substance of Mom has changed to somebody else while maintaining in appearance everything else that was a part of mom: her eyes, her hair, her nails. Those things that are a part of her appearance make up her accidents. On the other hand, to wrap our minds around the concept of changing a thing’s accidents, let’s think of ourselves in our own bodies. If I dye my hair or break my wrist, what changes are my accidents. My core substance remains the same: I am Deacon Paul Maxey.

Now let’s apply this to the Eucharist. When Jesus said at the Last Supper that bread was his body, the accidents of the bread remained the same. In other words, the bread, a microscope would show, continued to be bread. To all scientific tests, that bread would have remained bread. But like the mother who finds herself in her daughter’s body, the core substance of what the bread is changed. It’s not just that this same change of substance occurred at the Last Supper; it continues to occur every day at Mass. That is why when we receive the Eucharist at Mass, the eucharistic minister does not say, “This is bread”; rather, holding up the Eucharist, he says, “The body of Christ.” And we respond Amen, meaning, “I believe that this is truly the body of Christ.”

Jesus completely understands that this is difficult to comprehend and even to believe, so there have been times in history when the accidents of the bread and wine at Mass have turned into the body and blood of Christ as well. One such instance is the eucharistic miracle of Lanciano, Italy, which continues to this day. To put it briefly, a long time ago, the wine at Mass turned into actual blood in the chalice. Now Lanciano is a place of pilgrimage, where we can worship God, who is truly present in the blood of Christ.

We can reflect on the words of St. Epiphanius of Salamis (374) about the Last Supper. When Jesus took bread into his hands, as it says in the Gospel, “giving thanks, he said: ‘This is really me.’” (Epiphanius, The Man Well-Anchored, 57, in William Jurgen’s The Faith of the Early Fathers, vol. 2, 1084). There is something about those words that freshens up my understanding of the Eucharist.

We can think also of the words of St. John Chrysostom (370). When Jesus says, “‘This is my body,’ be convinced of it and believe it, and look at it with eyes of the mind” (Homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, 82, 4. in Jurgen’s vol. 2, 1,179). In other words, understand what’s happening even if your eyes can’t physically see the change.

If you wish that you could see Jesus as the apostles did, John Chrysostom reminds us to look at the Eucharist! “Only look! You see him! You touch him! You eat him!”

St. Ambrose of Milan (390-391) anticipated an objection: “Perhaps you may be saying: I see something else; how can you assure me that I am receiving the body of Christ?” (The Mysteries, 9, 50. in Jurgens, vol. 2, 1,333). He responds, “Let us prove that this is not what nature has shaped it to be, but what the blessing has consecrated; for the power of the blessing is greater than that of nature, because by the blessing even nature itself is changed.”

Next time we go to Mass, as the Eucharist touches our tongues, let us remember that we are receiving into our own body the living God himself!

Image from Disney’s Freaky Friday promotional poster, fair use.