Today is the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter. But why is the Church celebrating a feast day for a chair?

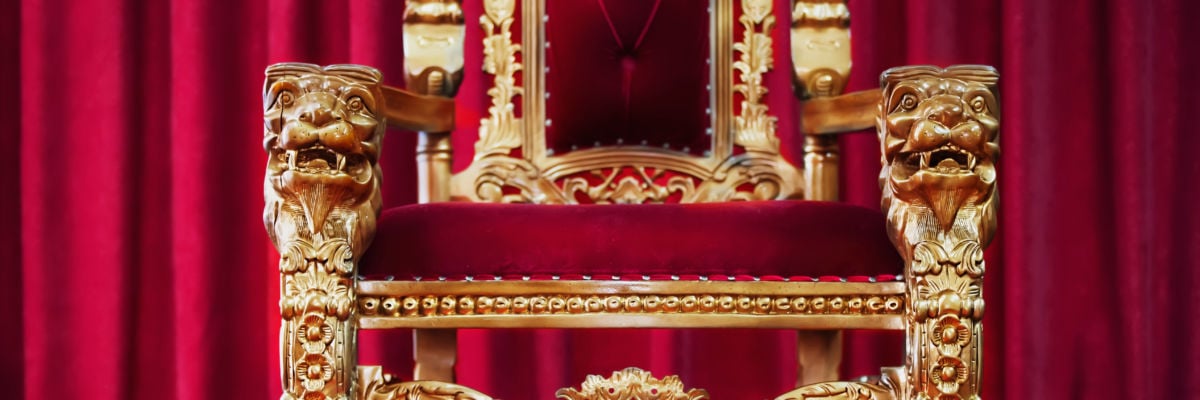

Chair here refers to the seat of authority, as when Jesus says that “the scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice” (Matt. 23:2-3). The Latin for chair, cathedra, is where we get words like cathedral, the seat of the bishop’s authority in his diocese. And so, when we refer to the Chair of St. Peter, we’re referring both to Peter’s authority and to his cathedra, the seat of his authority in Rome.

Pope Benedict XVI has pointed out that “this is a very ancient tradition, proven to have existed in Rome since the fourth century.” But what makes this chair so important? As St. Cyprian of Carthage noted back in the third century, this is “the throne of Peter” and “the chief church whence priestly unity takes its source.”

Throughout early Church history, we regularly find the chair of Peter serving just this role. When the East was torn apart by regular schisms and heresies, the church of Rome would help to preserve (or re-establish) the peace. For instance, St. Jerome, writing from the East in 376 or 377, appeals to Pope Damasus to help to clear up which of three rival claimants was the true bishop of Antioch. He begins his letter this way:

Since the East, shattered as it is by the long-standing feuds, subsisting between its peoples, is bit by bit tearing into shreds the seamless vest of the Lord, “woven from the top throughout,” since the foxes are destroying the vineyard of Christ, and since among the broken cisterns that hold no water it is hard to discover “the sealed fountain” and “the garden enclosed,” I think it my duty to consult the chair of Peter, and to turn to a church whose faith has been praised by Paul.

That doesn’t mean that union with the pope was always easy-going. Later in life, while feuding with Pope St. Stephen I, the same Cyprian who once praised Rome’s role in establishing “priestly unity” would lament that

Stephen, who announces that he holds by succession the throne of Peter, is stirred with no zeal against heretics, when he concedes to them, not a moderate, but the very greatest power of grace: so far as to say and assert that, by the sacrament of baptism, the filth of the old man is washed away by them, that they pardon the former mortal sins, that they make sons of God by heavenly regeneration, and renew to eternal life by the sanctification of the divine laver.

In other words, the zealous Cyprian was afraid that the pope had gone soft. But history has vindicated Stephen: provided that they were validly baptized, heretics do not need rebaptism.

Less saintly successors to Cyprian took his hardline stance on rebaptism to a new level, which helped to culminate in the Donatist schism. Writing against that schism in the fourth century, St. Optatus of Milevis appealed to Peter’s cathedra as a visible means of drawing Christians back from schism:

You cannot then deny that you do know that upon Peter first in the city of Rome was bestowed the episcopal cathedra, on which sat Peter, the head of all the apostles . . . that, in this one cathedra, unity should be preserved by all, lest the other apostles might claim—each for himself—separate cathedras, so that he who should set up a second cathedra against the unique cathedra would already be a schismatic and a sinner.

Optatus’s words have proved prophetic. In the middle of the fourth century, the Roman emperor transported the relics of the apostle Andrew to the new imperial capital in Constantinople. Eventually, local legend claimed that Andrew had personally preached in the city, and had in fact founded the local church of Byzantium. This historical claim is generally rejected. Fr. Francis Dvornik, one of the leading twentieth-century experts on Byzantine history, observed:

The tradition concerning the missionary activity of the apostle Andrew in Achaea and his death at Patras is regarded as legendary by the majority of modern scholars. The account of the apostle’s residence at Byzantium, where he is said to have ordained his disciple Stachys as the first bishop of that city, has likewise been shown to have little foundation in fact.

No mere idle legend, this was part of a broader political agenda to counterbalance the true apostolic see of Rome. St. Paulinus of Nola observed in the fifth century that as the Roman emperor “was then embarking on that splendid enterprise of building a city which would rival Rome,” he “removed Andrew from the Greeks and Timothy from Asia; and so with twin towers stands forth Constantinople, rivaling with her head the Great Rome.”

Although historically untrue, it was certainly attractive for the Byzantine East to claim that their “New Rome” was in fact founded by the very apostle who introduced Peter to Jesus (John 1:40-42). This rivalry between Constantinople and Rome would lead to the Great Schism between East and West, ultimately demonstrating the truth of Optatus’s claim that “he who should set up a second cathedra against the unique cathedra would already be a schismatic and a sinner.”

But what about within the West? Despite the role of the chair of Peter in establishing unity in the Church, it’s also been the source of great division and confusion. History has witnessed the rise of dozens of antipopes—men who claimed to be pope but weren’t.

Optatus anticipated this as well. After appealing to the authority of the chair of Peter in the city of Rome, he observed that the Donatists “allege that you too have some sort of a party in the city of Rome.” Optatus dismissed this argument by pointing out that if the Donatist priest in Rome were “to be asked where he sits in the city, will he be able to say on Peter’s cathedra? I doubt whether he has even set eyes upon it, and schismatic that he is, he has not drawn nigh to Peter’s ‘shrine.’” He continues with a challenge: “Behold, in Rome are the ‘shrines’ of the two apostles. Will you tell me whether he has been able to approach them, or has offered sacrifice in those places, where—as is certain—are these ‘shrines’ of the saints?” In other words, the true successor to Peter is the one who offers Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica and St. Paul’s Outside the Walls.

While not an infallible guide (in 1130, cardinals annoyed at the election of Pope Innocent II quickly “elected” an antipope, Anacletus II, who seized St. Peter’s, forcing the true pope to be consecrated in Santa Maria Nuova), the above story points to a truth about the nature of the chair of Peter. Jesus Christ established his Church to be “a city set on a hill [that] cannot be hid” (Matt. 5:14).

We aren’t left to figure out Christianity from our own personal interpretations of Scripture, or from picking between equally viable cathedras, or between equally viable papal claimants. Rather, Jesus makes it sufficiently clear who the true successor of Peter is so that we can remain united with him, and thus, with the true Church.