Apostolic Succession. —Apostolicity as a note of the true Church being dealt with elsewhere, the object of the present article is to show: (I) That Apostolic succession is found in the Roman Catholic Church. (2) That none of the separate Churches have any valid claim to it. (3) That the Anglican Church, in particular, has broken away from Apostolic unity.

ROMAN CLAIM.—The principle underlying the Roman claim is contained in the idea of succession. “To succeed” is to be the successor of, especially to be the heir of, or to occupy an official position just after, as Victoria succeeded William IV. Now the Roman Pontiffs come immediately after, occupy the position, and perform the functions of St. Peter; they are, therefore, his successors. We must prove (a) that St. Peter came to Rome, and ended there his pontificate; (b) that the Bishops of Rome who came after him held his official position in the Church. As soon as the problem of St. Peter’s coming to Rome passed from theologians writing pro domo sua into the hands of unprejudiced historians, i.e. within the last half century, it received a solution which no scholar now dares to contradict; the researches of German professors like A, Harnack and Weiasticker, of the Anglican Bishop Lightfoot, and those of archaeologists like De Rossi and Lanciani, of Duchesne and Barnes, have all come to the same conclusion: St. Peter did reside and die in Rome. Beginning with the middle of the second century, there exists a universal consensus as to Peter’s martyrdom in Rome; Dionysius of Corinth speaks for Greece, Irenaeus for Gaul, Clement and Origen for Alexandria, Tertullian for Africa. In the third century the popes claim authority from the fact that they are St. Peter’s successors, and no one objects to this claim, no one raises a counterclaim. No city boasts the tomb of the Apostle but Rome. There he died, there he left his inheritance; the fact is never questioned in the controversies between East and West. This argument, however, has a weak point: it leaves about one hundred years for the formation of historical legends, of which Peter’s presence in Rome may be one just as much as his conflict with Simon Magus. We have, then, to go farther back into antiquity. About 150 the Roman presbyter Caius offers to show to the heretic Proclus the trophies of the Apostles: “If you will go to the Vatican, and to the Via Ostiensis, you will find the monuments of those who have founded this Church.” Can Caius and the Romans for whom he speaks have been in error on a point so vital to their Church? Next we come to Papias (c. 138-150). From him we only get a faint indication that he places Peter’s preaching in Rome, for he states that Mark wrote down what Peter preached, and he makes him write in Rome. Weizsacker himself holds that this inference from Papias has some weight in the cumulative argument we are constructing. Earlier than Papias is Ignatius Martyr (before 117), who, on his way to martyrdom, writes to the Romans: “I do not command you as did Peter and Paul; they were Apostles, I am a disciple”, words which according to Lightfoot have no sense if Ignatius did not believe Peter and Paul to have been preaching in Rome. Earlier still is Clement of Rome writing to the Corinthians, probably in 96, certainly before the end of the first century. He cites Peter’s and Paul’s martyrdom as an example of the sad fruits of fanaticism and envy. They have suffered “amongst us” he says, and Weizsacker rightly sees here another proof for our thesis. The Gospel of St. John, written about the same time as the letter of Clement to the Corinthians, also contains a clear allusion to the martyrdom by crucifixion of St. Peter, without, however, locating it (John, xxi, 18, 19). The very oldest evidence comes from St. Peter himself, if he be the author of the First Epistle of Peter, or if not, from a writer nearly of his own time: “The Church that is in Babylon saluteth you, and so doth my son Mark” (I Peter, v, 13). That Babylon stands for Rome, as usual amongst pious Jews, and not for the real Babylon, then without Christians, is admitted by common consent (cf. F. J. A. Hort, “Judaistic Christianity“, London, 1895, 155). This chain of documentary evidence, having its first link in Scripture itself, and broken nowhere, puts the sojourn of St. Peter in Rome among the best-ascertained facts in history. It is further strengthened by a similar chain of monumental evidence, which Lanciani, the prince of Roman topographers, sums up as follows: `For the archaeologist the presence and execution of Sts. Peter and Paul in Rome are facts established beyond a shadow of doubt, by purely monumental evidence!” (Pagan and Christian Rome, 123).

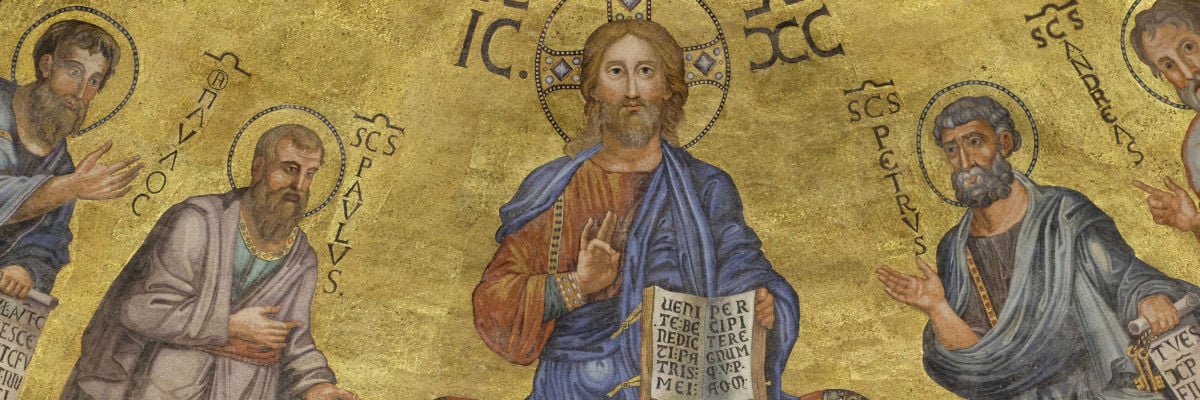

ST. PETER’S SUCCESSORS IN OFFICE., St. Peter’s successors carried on his office, the importance of which grew with the growth of the Church. In 97 serious dissensions troubled the Church of Corinth. The Roman Bishop, Clement, unbidden, wrote an authoritative letter to restore peace. St. John was still living at Ephesus, yet neither he nor his interfered with Corinth. Before 117 St. Ignatius of Antioch addresses the Roman Church as the one which “presides over charity… which has never deceived any one, which has taught others.” St. Irenaeus (180-200) states the theory and practice of doctrinal unity as follows: “With this Church [of Rome] because of its more powerful principality, every Church must agree, that is, the faithful everywhere, in which [i.e. in communion with the Roman Church] the tradition of the Apostles has ever been preserved by those on every side” (Adv. Haereses, III). The heretic Marcion, the Montanists from Phrygia, Praxeas from Asia, come to Rome to gain the countenance of its bishops; St. Victor, Bishop of Rome, threatens to excommunicate the Asian Churches; St. Stephen refuses to receive St. Cyprian’s deputation, and separates himself from various Churches of the East; Fortunatus and Felix, deposed by Cyprian, have recourse to Rome; Basilides, deposed in Spain, betakes himself to Rome; the presbyters of Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, complain of his doctrine to Dionysius, Bishop of Rome; the latter expostulates with him, and he explains. The fact is indisputable: the Bishops of Rome took over Peter’s Chair and Peter’s office of continuing the work of Christ [Duchesne, “The Roman Church before Constantine”, Catholic Univ. Bulletin (October, 1904) X, 429-450]. To be in continuity with the Church founded by Christ affiliation to the See of Peter is necessary, for, as a matter of history, there is no other Church linked to any other Apostle by an unbroken chain of successors. Antioch, once the see and center of St. Peter’s labors, fell into the hands of Monophysite patriarchs under the Emperors Zeno and Anastasius at the end of the fifth century. The Church of Alexandria in Egypt was founded by St. Mark the Evangelist, the mandatary of St. Peter. It flourished exceedingly until the Arian and Monophysite heresies took root among its people and gradually led to its extinction. The shortest-lived Apostolic Church is that of Jerusalem. In 130 the Holy City was destroyed by Hadrian, and a new town, Aelia Capitolina, erected on its site. The new Church of Aelia Capitolina was subjected to Caesarea; the very name of Jerusalem fell out of use till after the Council of Nice (325). The Greek Schism now claims its allegiance. Whatever of Apostolicity remains in these Churches founded by the Apostles is owing to the fact that Rome picked up the broken succession and linked it anew to the See of Peter. The Greek Church, embracing all the Eastern Churches involved in the schism of Photius and Michael Caerularius, and the Russian Church can lay no claim to Apostolic succession either direct or indirect, i.e. through Rome, because they are, by their own fact and will, separated from the Roman Communion. During the four hundred and sixty-four years between the accession of Constantine (323) and the Seventh General Council (787), the whole or part of the Eastern episcopate lived in schism for no less than two hundred and three years: namely, from the Council of Sardica (343) to St. John Chrysostom (389), 55 years; owing to Chrysostom’s condemnation (404-415), 11 years; owing to Acacius and the Henoticon edict (484-519), 35 years; in Monothelism (640-681), 41 years; owing to the dispute about images (726-787), 61 years; total, 203 years (Duchesne). They do, however, claim doctrinal connection with the Apostles, sufficient to their mind to stamp them with the mark of Apostolicity.

THE ANGLICAN CONTINUITY CLAIM.—The continuity claim is brought forward by all sects, a fact showing how essential a note of the true Church Apostolicity is. The Anglican High-Church party asserts its continuity with the pre-Reformation Church in England, and through it with the Catholic Church of Christ. “At the Reformation we but washed our face” is a favorite Anglican saying; we have to show that in reality they washed off their head, and have been a truncated Church ever since. Etymologically, “to continue” means “to hold together”. Continuity, therefore, denotes a successive existence without constitutional change, an advance in time of a thing in itself steady. Steady, not stationary, for the nature of a thing may be to grow, to develop on constitutional lines, thus constantly changing yet always the selfsame. This applies to all organisms starting from a germ, to all organizations starting from a few constitutional principles; it also applies to religious belief, which, as Newman says, changes in order to remain the same. On the other hand, we speak of a “breach of continuity” whenever a constitutional change takes place. A Church enjoys continuity when it develops along the lines of its original constitution; it changes when it alters its constitution either social or doctrinal. But what is the constitution of the Church of Christ? The answer is as varied as the sects calling themselves Christian. Being persuaded that continuity with Christ is essential to their legitimate status, they have excogitated theories of the essentials of Christianity, and of a Christian Church, exactly suiting their own denomination. Most of them repudiate Apostolic succession as a mark of the true Church; they glory in their separation. Our present controversy is not with such, but with the Anglicans who do pretend to continuity. We have points of contact only with the High-Churchmen, whose leanings towards antiquity and Catholicism place them midway between the Catholic and the Protestant pure and simple.

ENGLAND AND ROME.—Of all the Churches now separated from Rome, none has a more distinctly Roman origin than the Church of England. It has often been claimed that St. Paul, or some other Apostle, evangelized the Britons. It is certain, however, that whenever Welsh annals mention the introduction of Christianity into the island, invariably they conduct the reader to Rome. In the “Liber Pontificalis” (ed. Duchesne, I, 136) we read that “Pope Eleutherius received a letter from Lucius, King of Britain, that he might be made a Christian by his orders. “The incident is told again and again by the Venerable Bede; it is found in the Book of Llandaff, as well as in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; it is accepted by French, Swiss, German chroniclers, together with the home authorities Fabius Etheiward, Henry of Huntingdon, William of Malmesbury, and Giraldus Cambrensis. The Saxon invasion swept the British Church out of existence wherever it penetrated, and drove the British Christians to the western borders of the island, or across the sea into Armorica, now French Brittany. No attempt at converting their conquerors was ever made by the conquered. Rome once more stepped in. The missionaries sent by Gregory the Great converted and baptized King Ethelbert of Kent, with thousands of his subjects. In 5August 97ine was made Primate over all England, and his successors, down to the Reformation, have ever received from Rome the Pallium, the symbol of superepiscopal authority. The Anglo-Saxon hierarchy was thoroughly Roman in its origin, in its faith and practice, in its obedience and affection; witness every page in Bede‘s “Ecclesiastical History“. A like Roman spirit animated the nation. Among the saints recognized by the Church are twenty-three kings and sixty queens, princes, or princesses of the different Anglo-Saxon dynasties, reckoned from the seventh to the eleventh century. Ten of the Saxon kings made the journey to the tomb of St. Peter, and to his successor, in Rome. Anglo-Saxon pilgrims formed quite a colony in proximity to the Vatican, where the local topography (Borgo, Sassia, Vicus Saxonum) still recalls their memory. There was an English school in Rome, founded by King Ine of Wessex and Pope Gregory II (715-731), and supported by the Romescot, or Peter’s-pence, paid yearly by every Wessex family. The Romescot was made obligatory, by Edward the Confessor, on every monastery and household in possession of land or cattle to the yearly value of thirty pence.

The Norman Conquest (1066) wrought no change in the religion of England. St. Anselm of Canterbury (1093-1109) testified to the supremacy of the Roman Pontiff in his writings (in Matt., xvi) and by his acts. When pressed to surrender his right of appeal to Rome, he answered the king in court: “You wish me to swear never, on any account, to appeal in England to Blessed Peter or his Vicar; this, I say, ought not to be commanded by you, who are a Christian, for to swear this is to abjure Blessed Peter; he who abjures Blessed Peter undoubtedly abjures Christ, who made him Prince over his Church.” St. Thomas Becket shed his blood in defense of the liberties of the Church against the encroachments of the Norman king (1170). Grosseteste, in the thirteenth century, writes more forcibly on the Pope‘s authority over the whole Church than any other ancient English bishop, although he resisted an ill-advised appointment to a canonry made by the Pope.’ In the fourteenth century Duns Scotus teaches at Oxford “that they are excommunicated as heretics who teach or hold anything different from what the Roman Church holds or teaches.” In 1411 the English bishops at the Synod of London condemn Wycliffe’s proposition “that it is not of necessity to salvation to hold that the Roman Church is supreme among the Churches.” In 1535 Blessed John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, is put to death for upholding against Henry VIII the Pope‘s supremacy over the English Church. The most striking piece of evidence is the wording of the oath taken by archbishops before entering into office: “I, Robert, Archbishop of Canterbury, from this hour forward, will be faithful and obedient to St. Peter, to the Holy Apostolic Roman Church, to my Lord Pope Celestine, and his successors canonically succeeding… I will, saving my order, give aid to defend and to maintain against every man the primacy of the Roman Church and the royalty of St. Peter. I will visit the threshold of the Apostles every three years, either in person or by my deputy, unless I be absolved by apostolic dispensation… So help me God and these Holy Gospels.” (Wilkins, Concilia Angliae, II, 199.) Chief Justice Bracton (1260) lays down the civil law of this country thus: “It is to be noted concerning the jurisdiction of superior and inferior courts, that in the first place as the Lord Pope has ordinary jurisdiction over all in spirituals, so the king has, in the realm, in temporals.” The line of demarcation between things spiritual and temporal is in many cases blurred and uncertain; the two powers often overlap, and conflicts are unavoidable. During five hundred years such conflicts were frequent. Their very recurrence, however, proves that England acknowledged the papal supremacy, for it requires two to make a quarrel. The complaint of one side was always that the other encroached upon its rights. Henry VIII himself, in 1533, still pleaded in the Roman Courts for a divorce. Had he succeeded, the supremacy of the Pope would not have found a more strenuous defender. It was only after his failure that he questioned the authority of the tribunal to which he had himself appealed. In 1534 he was, by Act of Parliament, made the Supreme Head of the English Church. The bishops, instead of swearing allegiance to the Pope, now swore allegiance to the King, without any saving clause. Blessed John Fisher was the only bishop who refused to take the new oath; his martyrdom is the first witness to the breach of continuity between the old English and the new Anglican Church. Heresy stepped in to widen the breach.

The Thirty-nine Articles teach the Lutheran excellence, and admits the advantages derived from doctrine of justification by faith alone, deny purgatory, reduce the seven sacraments to two, insist on the fallibility of the Church, establish the king’s supremacy, and deny the pope’s jurisdiction in England. Mass was abolished, and the Real Presence; the form of ordination was so altered to suit the new views on the priesthood that it became ineffective, and the succession of priests failed as well as the succession of bishops. (See Anglican Orders.) Is it possible to imagine that the framers of such vital alterations thought of “continuing” the existing Church? When the hierarchical framework is destroyed, when the doctrinal foundation is removed, when every stone of the edifice is freely rearranged to suit individual tastes, then there is no continuity, but collapse. The old facade of Battle Abbey still stands, also parts of the outer wall, and the old name remains; but pass through the portal, and one faces a stately, newish, comfortable mansion; green lawns and shrubs hide old foundations of church and cloisters; the monks’ scriptorium and storerooms still stand to sadden the visitor’s mood. Of the abbey of 1538, the abbey of 1906 only keeps the mask, the diminished sculptures and the stones—a fitting image of the old Church and the new.

PRESENT STAGE.—Dr. James Gairdner, whose “History of the English Church in the 16th Century” lays bare the essentially Protestant spirit of the English Reformation, in a letter on “Continuity” (reproduced in the Tablet, January 20, 1906), shifts the controversy from historical to doctrinal ground. “If the country”, he says, “still contained a community of Christians—that is to say, of real believers in the great gospel of salvation, men who still accepted the old creeds, and had no doubt Christ died to save them—then the Church of England remained the same Church as before. The old system was preserved, in fact all that was really essential to it, and as regards doctrine nothing was taken away except some doubtful scholastic propositions.” (See Apostolicity; Saint Peter; Antioch; Alexandria; Greek Church; Anglicanism; Anglican Orders.)

J. WILHELM