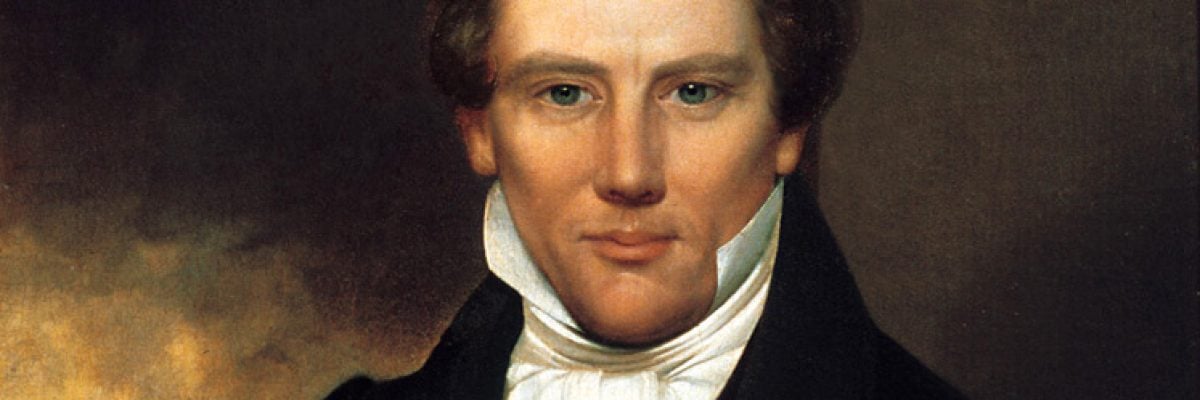

Are Mormons Protestants? No, but their founder, Joseph Smith, came from a Protestant background, and Protestant presuppositions form part of the basis of Mormonism.

Still, it isn’t correct to call Mormons Protestants, because doing so implies they hold to the essentials of Christianity—what C. S. Lewis termed “mere Christianity.” The fact is, they don’t. Gordon B. Hinckley, a former president and “prophet” of the Mormon church, says (in a booklet called What of the Mormons?) that he and his co-religionists “are no closer to Protestantism than they are to Catholicism.”

That isn’t quite right—it would be better to say Mormons are even further from Catholicism than from Protestantism. But Hinckley is right in saying that Mormons are very different from Catholics and Protestants. Let’s examine some of these differences. We can start by considering the young men who come to your door.

They always come in pairs and are dressed conservatively, usually in white shirts and ties. As often as not, they get from place to place by bicycle. They introduce themselves to you as Elder This and Elder That. The title “Elder” does not refer to their age (many are not even shaving regularly yet), but means they hold the higher of the two Mormon priesthoods: the “Melchizedek” order. This priesthood is something every practicing Mormon male is supposed to receive at about age eighteen, provided he conforms to the standards of the church.

The other priesthood—the “Aaronic”—is the lesser of the two and is concerned with the temporal affairs of the church; and its ranks are known as deacon, teacher, then priest.

The Melchizedek priesthood is concerned mainly with spiritual affairs, and it “embrac[es] all of the authority of the Aaronic,” explains Hinckley. The Melchizedek ranks are elder, seventy, and high priest. At age twelve boys become deacons and thus enter the “Aaronic priesthood.”

If the terms for the various levels of the Mormon priesthood are confusing, still more confusing is Mormonism’s ecclesiastical structure. The basic unit, equivalent to a very small parish, is the “ward.” Several wards within a single geographical area form a “stake,” which corresponds to a large Catholic parish. The head of each ward isn’t called a priest, as you might expect, but a bishop. A Mormon bishop can officiate at a civil marriage, but not at a “temple marriage,” which can be performed only by a “sealer” in one of Mormonism’s temples.

Polygamy

Mormons try to attract new members by projecting an image of wholesome family life in their circles. This is an illusion—Mormon Utah has higher-than-average rates for suicide, divorce, and other domestic problems than the rest of the country. And if Mormonism’s public image of large, happy families and marriage bring to mind anything, it is polygamy.

Hinckley explains that “Mormonism claims to be a restoration of God’s work in all previous dispensations. The Old Testament teaches that the patriarchs . . . had more than one wife under divine sanction. In the course of the development of the church in the nineteenth century, it was revealed to the leader of the church that such a practice should be entered into again.” Although polygamy was permitted to Mormons, few practiced it. But enough did so to make polygamy the characteristic that most caught the attention of other Americans.

Mormonism: Made in America

If some of today’s Protestants are known for their belief that America is destined to play a key role in the events of the Last Days, Mormons are identified even more closely with America. The Mormons’ theory is that Christ also established his Church here, among the Indians, where it eventually flopped, as did his original effort in Palestine.

The situation is somewhat similar to that of the Anglican church. In England, the Anglican church is not just the church of Englishmen; it is the Established Church. In theory, and even at times in practice, Parliament can decide what Anglicans are to believe officially and can make and unmake clerics of all grades, from the lowliest curate to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Just as Anglicanism is tied to England, so Mormonism is tied to the United States. Although it is not the established religion of this country, Mormonism has allowed itself to be modified by Congress.

“In the late 1880s,” says Hinckley, “Congress passed various measures prohibiting [polygamy]. When the Supreme Court declared these laws constitutional, the church indicated its willingness to comply. It could do nothing else in view of its basic teachings on the necessity for obedience to the law of the land. That was in 1890. Since then officers of the church have not performed plural marriages, and members who have entered into such relationships have been excommunicated.”

Before Congress acted, Mormons were convinced polygamy was not merely permissible, but positively good, for those “of the highest character who had proved themselves capable of maintaining more than one family.” Yet this position was dropped when Congress threatened to deny statehood to Utah. Similarly, and more recently, a “revelation” saying blacks would no longer be denied the Mormon priesthood was given to Mormon leaders when the federal government became involved.

Continuing Revelation

These continuing revelations are not exceptions to Mormon practice. “We believe all that God has revealed, all that he does now reveal, and we believe that he will yet reveal many great and important things”—this is the ninth article of faith for Mormons and is an official statement of doctrine.

Hinckley notes that “Christians and Jews generally maintain that God revealed himself and directed chosen men in ancient times. Mormons maintain that the need for divine guidance is as great or greater in our modern, complex world as it was in the comparatively simple times of the Hebrews.” Thus, revelation continues.

It might be added: public revelation continues. Catholics hold that public or “general” revelation ended at the death of the last apostle (Catechism of the Catholic Church 66, 73), but private revelations can be given still—and have been, as Marian apparitions at such places as Fatima and Lourdes testify (CCC 67). But such revelations can never correct, supplement, or complete the Christian faith, which is precisely what Mormon “revelations” claim to do.

Mormonism’s Debt to Puritanism

“Mormon theology,” says Hinckley, “deals with such widely diversified subjects as the nature of heaven and the evils of alcohol. Actually, in this philosophy the two are closely related. Since man is created in the image of God, his body is sacred. . . . As such, it ill becomes any man or women to injure or dissipate his or her health.” So alcohol (as well as tobacco, tea, and caffeine) is out for the believing Mormon.

Here we have an example of Mormonism borrowing from Puritanism. The emphasis on “temperance”—which, to the old-line Protestants, meant not the moderate use of alcohol, but outright abstinence—is one such borrowing. The curious thing is that this attitude is contrary to the Bible.

Jesus Wasn’t a Teetotaler

The ancient Jews were a temperate people—temperate used in the right sense. They used light wine as part of the regular diet (1 Tim. 3:8). Jesus, you will recall, was called a wine-drinker (Matt. 11:19), the charge being not that he drank, but that he drank too much (that, of course, was false, but the charge itself reflects the fact that he did drink alcoholic beverages, such as the wine that was required for use in the Jewish Passover seder).

The New Testament nowhere says the Jews claimed Jesus should have been a teetotaler. Wine was used also at weddings, and our Lord clearly approved of the practice of wine drinking, since he made wine from water when the wine was depleted at Cana (John 2:1–11).

Something Mormons seldom refer to is wine’s medicinal uses (Luke 10:34). You will recall that Paul advised Timothy to take wine to ease stomach pains (1 Tim. 5:23). Such apostolic admonitions coexist uneasily with Mormonism’s strictures against wine.

Mormons practice tithing, yet would be shocked to learn that in a key Old Testament passage where tithing (the practice of donating 10 percent of one’s income for religious use) is discussed, God says: “you shall turn [your tithe] into money, and bind up the money in your hand, and go to the place which the Lord your God chooses, and spend the money for whatever you desire, oxen, or sheep, or wine or strong drink, whatever your appetite craves; and you shall eat there before the Lord your God and rejoice, you and your household” (Deut. 14:25-26). We’re also told, “Give strong drink to him who is perishing, and wine to those in bitter distress; let them drink and forget their poverty, and remember their misery no more” (Prov. 31:6–7).

Often when founders of new religions get an idea, they take it to an extreme. So Joseph Smith confused the misuse of wine with its legitimate use. The Bible does condemn excessive drinking (1 Cor. 5:11; Gal. 5:21; Eph. 5:18; 1 Pet. 4:3), but the key here is the adjective “excessive.”

Plural Heavens

Mormonism teaches that practically no one is forever damned to hell. Aside from Satan, his spirit followers, and perhaps a half-dozen notorious sinners, all people who have ever existed will share in heavenly “glory.” Not, mind you, all in the same heaven. There are, in fact, three heavens.

The lowest heaven is populated by adulterers, murderers, thieves, liars, and other evildoers. These share in a glory and delight impossible to imagine. Their sins have been forgiven, and they now enjoy the eternal presence of the Holy Ghost.

The middle heaven contains the souls and bodies of good non-Mormons and those Mormons who were in some way deficient in their obedience to church commandments. They will glory in the presence of Jesus Christ forever.

The top heaven is reserved for devout Mormons, who go on to become gods and rulers of their own universes. By having their wives and children “sealed” to them during an earthly, temple ceremony, these men-gods will procreate billions of spirits and place them into future, physical bodies. These future children will then worship their father-gods, obeying Mormon commandments, and eventually take their place in the eternal progression to their own godhood.

Mormons think this doctrine is a strong selling point. They point out (erroneously) that only their church offers families the chance to be together forever in eternity. But read the fine print. The only way you can have your family with you is if each one of them has lived a sterling Mormon life. Otherwise, a spouse, parent, or child may be locked forever in a lower heaven. Indeed, the faithful Mormon wife of a lukewarm Mormon man will leave him behind in an inferior place while she goes on and is sealed to a more devout Mormon gentleman. These two will then beget and raise their own, new family.

The LDS slogan, “Families are forever,” means fractured families.

NIHIL OBSTAT: I have concluded that the materials

presented in this work are free of doctrinal or moral errors.

Bernadeane Carr, STL, Censor Librorum, August 10, 2004

IMPRIMATUR: In accord with 1983 CIC 827

permission to publish this work is hereby granted.

+Robert H. Brom, Bishop of San Diego, August 10, 2004