Since Pope John Paul II called the Church to a new “horizon of evangelization,” there has been increased interest in the mission of evangelization. Parishes and dioceses throughout the United States have active evangelization teams and offices of evangelization. Yet, as central as evangelization is to the mission and life of the Church, there is still reluctance on the part of many Catholics to become involved in it.

Catholics Don’t Do That

Some years ago, I was assigned to a small parish where the pastor wanted to implement a parish-based evangelization team. The idea was that after a time of formation, three teams would be formed. The first team would focus on enriching the actively practicing and involved Catholics in the parish. The second team would reach out to lapsed Catholics in the parish. The third team would contact non-Catholics by providing informal visits to their homes.

We began by soliciting interest from among parish lay leadership. I was rather surprised by the response that came from many of those active parishioners who were asked to join the team. One woman’s comment is characteristic: “We are not interested in evangelization.” Still another comment spoke volumes to me of the need for evangelization, not to mention basic catechesis: “Catholics don’t do things like that!”

Despite the initial resistance, we moved forward with the spiritual and theological formation. An early part of that formation was a day of recollection where we introduced the ancient art of lectio divina (divine reading). After learning the four-phase method of lectio divina, each of the participants was given a Scripture passage that included the Gospel imperative to evangelize. Next, having spent time in private prayer as individuals, small groups came together to share their experiences. It was very apparent by the depth and conviction of the reflections that the Scripture had spoken to hearts. Many participants felt that their prayer had been a channel of God’s grace—and they felt called to the mission of evangelization.

The ancient practice of lectio divina offers a channel of grace to the new horizon of evangelization. It affords an ideal opportunity to listen to the Word of God in the “ear of one’s heart” (The Rule of Benedict); at the same time it provides a very useful and practical component for parish-based or diocesan evangelization.

Among the various schools of prayer, lectio divina has perhaps the longest, the most significant, and the most venerable tradition. Looking back through the millennia of salvation history we can see how a lectio divina type of prayer was central to the spiritual practice of the faithful in ancient Israel. The teachers read Scripture to the people and the people would memorize the scriptures and meditate over them “day and night” (Ps 1:2).

The Gospels clearly portray Jesus as the man of prayer, steeped in the scriptures. Jesus himself engaged in a form of lectio divina when on one occasion in the synagogue he read the scriptures and proclaimed “Today this scripture passage has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Lk 4:16-21). As the Church evolved as a distinct identity, the tradition of scriptural prayer from Judaism was absorbed into the fabric of Christian life and spirituality. It is clear that scriptural prayer was a common practice in the early Church as exemplified by the Church in Alexandria, where Origen instructed Christians in the practice of scriptural reading and meditations. This was originally termed sacra pagina, but gradually developed into what is called today lectio divina.

What Is Divine Reading?

Divine reading is sapiential, not scientific reading, meaning that we read it to gain wisdom rather than factual knowledge. There is a great distinction: While we seemingly find knowledge on our own, it is grace that leads us to wisdom. Lectio divina requires the grace of God and the engagement of the whole person: will, intellect, and heart. As we seek to know the heart of man and God in the Word of God, the path to evangelization becomes clear.

To evangelize, it is necessary to be evangelized oneself. Scriptural prayer leads to conversion and conversion of life. It provides real food for spiritual strength and purification—and these are the arsenal of weapons for spiritual warfare against all that opposes growth in love and truth. Lectio divina enables us to cooperate with the graces received in baptism to fulfill Christ’s universal call to holiness.

The art of listening is essential to lectio divina, and listening is the fundamental tool and stance of every authentic disciple of Jesus. Listening is the thread running through the fabric of lectio divina and throughout all of Christian life. This is expressed in the Rule of Benedict as the gateway through which obedience, humility, and silence flow. These virtues, combined with charity and solid catechesis, will form the foundation for effective evangelization.

As Easy as LMOC

Lectio divina as a form of prayer has four interdependent phases. These phases can be remembered by the acronym LMOC, its meaning translated from the Latin: lectio or reading, meditatio or meditation, oratio or prayer, and contemplatio or contemplation. The process begins with reading. The purpose of this type of reading is not to glean content, nor is it to be expedient and efficient—these would not be the keys to prayerful reading. This type of reading must be patient, persistent, disciplined, and open to the working of the Holy Spirit. It must above all avoid haste.

To begin, the sacred text should be read in a slow, deliberate way, focusing on the words and nothing else, not even the meaning, but only the words themselves. This type of reading has been compared to the ruminating of cows—an earthy, but accurate, metaphor. As one reads the passage over and over, a particular word or phrase will emerge or “glow” with meaning. This will become the word of grace or the anchor phrase for the day’s prayer. During these periods of silent attention, the words of Scripture penetrate the soul and etch themselves on the heart.

The reading phase leads to the next interdependent phase, which is meditation. Meditation comes from the Latin and means (loosely translated) “to think.” It does not mean thinking in the general sense, but thinking that includes an intent to act upon what that thinking leads us to do. Now, with the help of the Holy Spirit, apply your will, thoughts, imagination, emotions, and desire to discern and deliberate the meaning and significance of this word for today.

The fruits of meditation are brought to bear in the next phase of lectio divina, which is prayer. This is a natural transition, where one is drawn into dialogue with God as a result of meditation. In this phase, the word of God gently transitions from just the rational mind to penetrate the heart ever deeper. It is during prayer that we become most deeply ourselves. Awareness of God’s ineffable love and our complete dependence upon him leads us into deeper communion with him.

We approach God with our entire selves, calling upon all of our natural and supernatural faculties. This is an act of the intellect, moved by the will, in concordance with and perfected and elevated by faith, hope, and charity.

Be Still and Know that I Am God

Now, having spoken from the depths of the heart to God in the act of prayer, during the fourth phase we seek to listen to the heart of God. This phase is called contemplation. The word contemplation is derived from the Latin word templem and it loosely translates as “to look at a spectacle.” The preceding three phases are considered active prayer because they engage the intellect and the will in an active way. The contemplation phase is passive prayer, as it seeks the direct experience of God as far as possible. Contemplation is the knowledge of God through faith and experienced through love. It is an intuitive experience of God made possible through faith, hope, charity, and the gift of wisdom (Jordan Aumann, Spiritual Theology, 258). At this time in the experience of lectio divina, the goal is to be completely present to God. We are still and allow ourselves to be a blank slate so that God may write on us whatever he will. This is the place in prayer where God may take over completely as we close down intellect, will, and imagination. St. John of the Cross says “to do nothing: to exert no effort, to have no desire, and to allow the love of God to compel one’s soul to freely enter into silence, simply to receive” (Whitall Perry, A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom, 253).

There is a fifth phase of lectio divina, not traditionally included, and that is operatio. In this phase, the experience of prayer is taken out into the world and acted upon. Whereas holiness is a difficult thing to measure, its fruits are not. Scripture reminds us that a tree is known not by its first appearance but by its fruit. The fruit of prayer should be the burning desire to bring the Good News to the ends of the earth, as Christ commanded.

Not Just for the Cloister

Having seen the great practical value of lectio divina for evangelization, it would be a serious error to relegate it to a monastic cloister or, worse, history. It has in every age been an inestimable gift of God to move the hearts of men. Today, it is an essential tool in the new evangelization. Scriptural prayer allows us to understand our own lived experience and the experiences of others so that we can present Christ and his gospel in a way that is relevant and life-giving. Only this will bring true peace, justice, and freedom to our world, and only this will satisfy the longing of the human heart.

SIDEBAR

Lectio Divina through the Ages

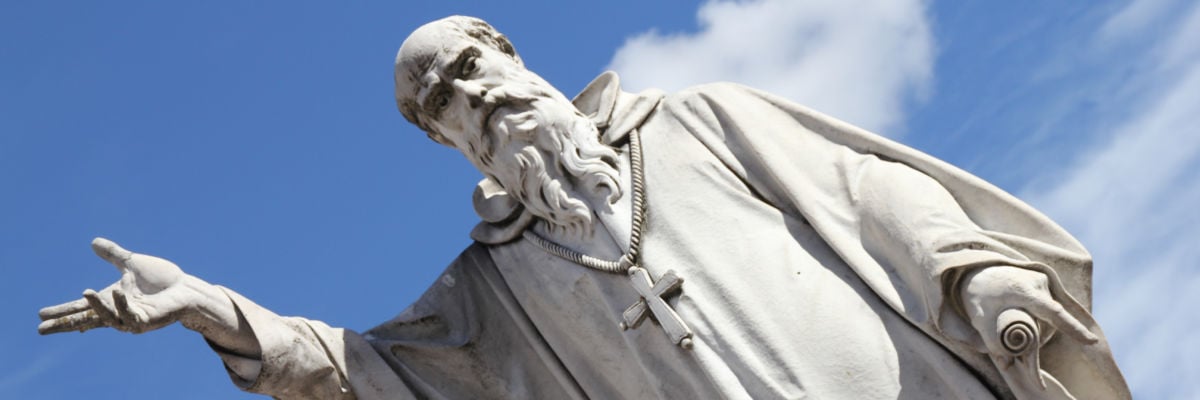

During the patristic period, the fathers of the East and the West used lectio divina and encouraged its use among the faithful. Perhaps the first to do so was St. Cyprian of Carthage, who counseled a young monk to “be assiduous in prayer and reading” (Epistle 1.15). St. Ambrose of Milan writes “We speak to God when we pray, we listen to God when we read God’s Word” (qtd. in Theological and Dogmatic Works).

Certainly one of the most profound experiences of lectio divina was in the life of St. Augustine of Hippo, and is described in his Confessions. Augustine had been reading, meditating, and contemplating the Psalms when he heard a voice say to him, “Go sell what you have, and give to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven, and come follow me” (Confessions VIII).

But the name most closely identified with lectio divina is that of St. Benedict of Nursia (c. 530). St. Benedict gave lectio divina its name in his Rule of St. Benedict, and established its inseparable link in the West with monasticism. He codified lectio divina in his Rule, mandating specific times each day for the monk to practice scriptural reading and prayer (48).

In the Scholastic period, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Bonaventure and many other theologians advocated scriptural prayer, encouraging the faithful to put questions to Scripture and then to ask themselves questions about the form and content of what they had read (Jean LeClercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, 78). The Modern Period was a golden age for writing on meditation and contemplation. During this time the Church further developed the understanding of prayer as dialogue with God who initiates the dialogue through his Word (“Prayer,” The New Catholic Encyclopedia).

In the last century, lectio divina has experienced a profound revival beginning in 1927 with Denis Gorcs and continuing with the liturgical movement of the 1940s and 1950s. The Second Vatican Council emphasized the value of lectio divina in the decree Dei Verbum: “prayer should accompany the reading of Sacred Scripture, so that a dialogue takes place between God and man” (25).