The earliest text concerning the Real Presence is found in Paul’s first epistle to the Corinthians, written probably about A.D. 57, or 27 years after Christ’s death. Modern scholars believe Jesus died in the year 30 and that Saul was converted early in 37. Some are convinced his conversion was as early as 34. It seems certain that 1 Corinthians was written after the Passover of 57. This means the newly converted Saul, now Paul, was plunged into the infant Church as early as four and not later than seven years after the death of Christ. He was an eyewitness of the earliest Eucharistic celebrations or liturgical practices. Consider this in light of what Vatican I taught about Revelation: “After the Ascension of the Lord the apostles handed on to their hearers what he had said and done. They did this with a clear understanding, which they enjoyed after they had been instructed by the events of Christ’s risen life and taught by the light of the Spirit of truth” (Decree on Revelation, 19).

Paul’s Eucharistic teaching in 1 Corinthians leaves us in no doubt. “For this is what I received from the Lord and in turn passed on to you: That on the same night as he was betrayed, the Lord Jesus took some bread, and thanked God for it, and broke it, and he said, ‘This is my body which is for you; do this as a memorial of me.’ In the same way he took the cup after supper and said, ‘This cup is a new covenant in my blood. Whenever you drink it, do this as a memorial of me.’ Until the Lord comes, therefore, every time you eat this bread and drink this cup, you are proclaiming his death. And so anyone who eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord unworthily will be behaving unworthily toward the body and blood of the Lord. Everyone is to recollect himself before eating this bread and drinking this cup, because a person who eats and drinks without recognizing the body is eating and drinking his own condemnation” (1 Cor. 11:23-29).

In the previous chapter the apostle wrote, “The blessing-cup that we bless is a communion with the blood of Christ, and the bread that we break is communion with the body of Christ” (1 Cor. 10:16). His words are clear. The only possible meaning is that the bread and wine at the consecration become Christ’s actual body and blood. Evidently Paul believed that the words Christ had said at the Last Supper, “This is my Body,” meant that really and physically the bread is his body. In fact Christ was not merely saying that the bread was his body; he was decreeing that it should be so and that it is so.

Paul and Christians of the first generation understood the doctrine in this thoroughly realistic way. They knew how our Lord demanded faith, as we read in John 6. Belief in the Eucharist presupposes faith. The body that is present in the Eucharist is that of Christ now reigning in heaven, the same body which Christ received from Adam, the same body which was made to die on the cross, but different in the sense that it has been transformed. In the words of Paul, “It is the same with the resurrection of the dead; the thing that is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable; the thing that is sown is contemptible, but what is raised is glorious; the thing that is sown is weak, but what is raised is powerful; when it is sown it embodies the soul, when it is raised it embodies the spirit” (1 Cor. 15:42-44). This spiritualized body was a physical reality, as Thomas discovered. “Put your finger here; look, here are my hands. Give me your hand and put it into my side” (John 20:27). It is this glorious body which is now, under the appearance of bread, communicated to us.

We know that Paul writes that he is handing on a tradition which he received from the Lord. He tells the Galatians, “The good news I preach is not a human message that I was given by men, it is something I learned only through a revelation of Jesus Christ” (Gal. 1:11-12). Likewise to the Philippians: “Keep doing all the things that you have learned from me and have been taught by me and have heard or seen that I do” (Phil. 4:9). To the Colossians he writes, “You must live your whole life according to the Christ you have received–Jesus the Lord” (Col. 2:6).

If Paul is handing on a tradition, we ask where it comes from. Clearly it stems from Christ. Paul stresses this over and over. “Through the good news that we brought he called you to this so that you should share the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ. Stand firm, then, brothers, and keep the traditions that we taught you, whether by word of mouth or by letter” (2 Thess. 2:14-15). In the same way he said to Timothy, “Keep as your pattern the sound teaching you have heard from me” (2 Tim. 1:13). The apostle is not referring to just any kind of tradition. His is a tradition that must be believed because Christ himself proclaimed it with his own authority. Christ is the fountainhead of all God’s wonderful work. He is the Master, and we must submit to his teaching. “You call me Master and Lord and rightly so: So I am” (John 13:14).

One of the commonest errors of religious people in our day is to think that Christ was mainly a preacher, a holy man who went about organizing public meetings and urging people to repentance. The truth is that the most important thing Christ did was not to preach or to work miracles, but to perpetuate his work by gathering disciples around him. He sent his twelve apostles out to preach. “He summoned his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits with power to cast them out and to cure all kinds of diseases and sickness . . . These twelve Jesus sent out instructing them as follows . . . ” (Matt. 10:1-4). The apostles he trained specially for this work. The teaching he gave them became sacred Tradition.

We discover more about the beginnings and development of Christian Tradition from what is now known about the roles of Master and pupil in the Hebrew world. Our Lord was Master, and his followers were his pupils. They were being trained to hand on the living word which was to save the world. The disciples not only listened but followed. “Lord to whom shall we go? You have the message of eternal life, and we believe; we know that you are the holy one of God” (John 6:68). They did not just come and listen and go away, resolving to amend their lives. They became the personal disciples of Christ, being trained to carry more than his words to the world, as we shall see.

One of the characteristics of Hebrew schools was that the pupil or disciple would do anything possible in order to retain fully and exactly his master’s teaching. The ideal of every pupil was to be able to reproduce this teaching word for word. That ideal often was attained. This must have been the attitude of the first Christians. They were lovers of Christ, believers in his Godhead. They passionately wanted to retain all that God wished them to remember of the saving word. They had the privilege of receiving personal instruction from the greatest of all teachers, God himself. They had been told that what they were being taught was a treasure they had to pass on to succeeding generations. Theirs was no ordinary schooling. They were filled, absorbed with love. Above all, the Spirit of God was with them, teaching, guiding, and inspiring them.

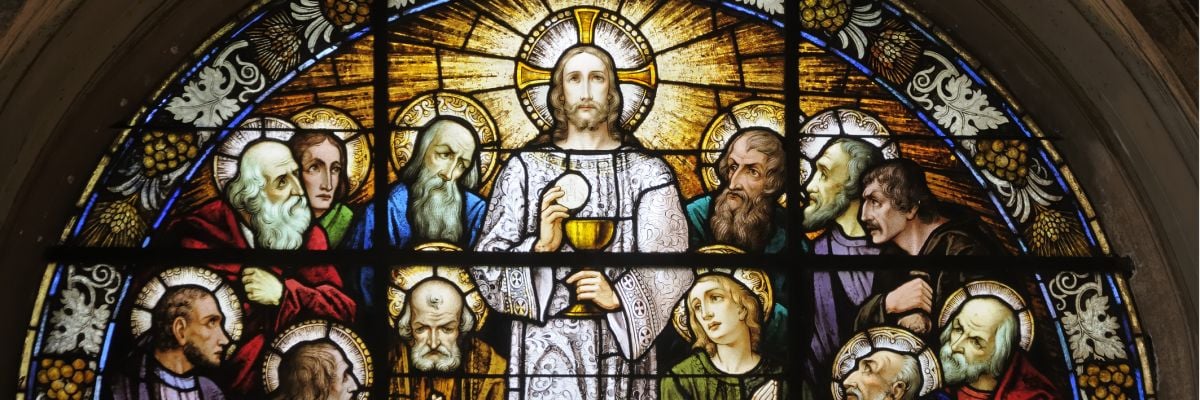

Three of the Gospels–Matthew, Mark, and Luke–tell us what happened at the Last Supper. Each has its own character, mode of writing, and variants. We do not expect in this type of writing photographic, meticulous, verbal identity. It is the essential truth that matters.

We shall never understand the New Testament unless we remember that these written accounts are simply versions of the verbal tradition. Paul and the evangelists knew what the Christians were doing. The words of consecration were being said at the Eucharistic meals. It was easy enough to write them down. There could have been no distortion, at the most only a simplification. Suppose we had been present with the apostles in those days between Christ’s Resurrection and his Ascension. We should have heard Christ teaching them. Indeed this was a most important time of their training. Can we imagine that he would omit to tell them in detail how they were to carry on doing what he told them to do at his Last Supper? Christ knew and they knew that this was to be the very heart of the worship of the Church he founded.

So there is not the slightest doubt that the formulas given us by the evangelists and Paul were those that were being used by the Christians as they celebrated the Eucharist. The Gospels faithfully hand on what Jesus Christ, while still living among men, really did and taught for their eternal salvation until the day he was taken up to heaven. Could anything at all be more important than what he did and said about his body and blood? Our Lord’s last meal was a Paschal feast, or at least a meal in the atmosphere of a Paschal feast, as he said. We know from Jewish writers how this can easily be fitted in to the full Jewish rite. The ancient commemorative meal of the Hebrews in which they recalled how God had freed his people from Egypt, was now to give place to a commemoration and reenactment of a new and final reality issuing from the mind and will of the risen Christ.

In the eleventh century Berengarius fell into heresy by failing to realize this point. His motto was, “I wish to understand all things by reason.” The Eucharist is one of those things which cannot be understood by reason. Human arguments can never explain Christ’s Real Presence.

John Chrysostom is known as “the Doctor of the Eucharist.” In 398 he became Patriarch of Constantinople. He wrote, “We must reverence God everywhere. We must not contradict him, when what he says seems contrary to our reason and intelligence. His words must be preferred to our reason and intelligence. This ought to be our behavior to the Eucharistic mysteries too. We must not confine our attention to what the senses can experience, but hold fast to his words. His word cannot deceive.” Writing of the words of institution he said, “You may not doubt the truth of this; you must rather accept the Savior’s words in faith; since he is truth, he does not tell lies.”

Centuries later Thomas Aquinas, the greatest of the scholastic theologians, taught the same. He said that the existence in the Eucharist of Christ’s real body and blood “cannot be grasped by the experience of the senses, but only by the faith which has divine authority and its support.” He put it into his famous verse: “Sight, touch, and taste in thee are each deceived; the ear alone most safely is believed; I believe all the Son of God has spoken, than through his own word there is no truer token.”

When Christ himself promised his Real Presence in the Eucharist, many of his disciples could not accept it. “This is intolerable language. How could anyone accept it?” (John 6:68). But Peter had the right mentality. “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the message of eternal life, and we believe; we know that you are the holy one of God” (John 6:69).

Here is a grave admonition of Pope Paul: “In the investigation of this mystery we follow the Magisterium of the Church like a star. The redeemer has entrusted the word of God, in writing and in tradition, to the Church’s Magisterium to keep and to explain. We must have this conviction: ‘what has since ancient times been preached and received with true Catholic faith throughout the Church is still true, even if it is not susceptible of a rational investigation or verbal explanation’ (Augustine).”

But the Pope goes on to say something that is vitally important. He says that it is not enough merely to believe the truth. We must also accept the way the Church has devised to express that truth exactly. Here is what he says: “When the integrity of faith has been preserved, a suitable manner of expression has to be preserved as well. Otherwise our usual careless language may . . . give rise to false opinions in belief in very deep matters.”

Pope Paul does not hesitate to declare that the language the Church has used to describe and explain its teaching has been adopted “with the protection of the Holy Spirit.” It has been confirmed with the authority of the councils. More than once it has become the token and standard of the orthodox faith. You have only to read the history of theology in the fourth and fifth centuries to understand how important the use of words was in indicating the true nature of Christ in those times. Then orthodoxy turned upon slight variations in a Greek word. The Holy Father says that this traditional language must be observed religiously. “Nobody may presume to alter it at will or on the pretext of new knowledge. It would be intolerable if the dogmatic formulae which ecumenical councils have employed in dealing with the mysteries of the Most Holy Trinity were to be accused of being badly attuned to the men of our day and other formulae were rashly introduced to replace them. It is equally intolerable that anyone on his own initiative should want to modify the formulae with which the Council of Trent has proposed the Eucharistic mystery for belief.”

This is a most important point. We must believe that the Council of Trent had the assistance of the Holy Spirit, as any general council has. The Pope then goes on to say that the Eucharistic formulae of the Council of Trent express ideas which are not tied to any specified cultural system. Presumably he is refuting the notion that the distinction we are going to discuss between substance and accidents is peculiar to scholastic philosophy and would be rejected by other thinkers. The Pope says, “They are not restricted to any fixed development of the sciences, nor to one or other of the theological schools. They present the perception which the human mind acquires from its universal essential experience of reality and expresses their use of appropriate and certain terms borrowed from colloquial or literary language. They are, therefore, within the reach of everyone at all times and in all places.”

It would be hard to overemphasize this point. In particular we might say that right thought always distinguishes between what a thing is and what it has. You do not need to be a scholastic philosopher to make a simple distinction of that sort. The Pope goes on to say that most things are capable of being explained more clearly, but explanation must not take away their original meaning. Vatican I defined that “that meaning must always be retained which Holy Mother Church has once declared. There must never be any retreat from that meaning on the pretext and title of higher understanding.”

There is particular significance in the fact that the dogmas of Christ’s Real Presence in the Eucharist remained unmolested down to the ninth century. Even then the molestation was comparatively slight. There were three great Eucharistic controversies which helped to clarify the ideas of theologians.

The first was begun by Paschasius Radbertus in the ninth century. The trouble he caused hardly extended beyond the limits of his audience and concerned itself only with the philosophical question whether the Eucharistic body of Christ is identical with the natural body he had in Palestine and now has glorified in heaven.

The next controversy arose over the teaching of Berengarius, to whom we have already referred. He denied transubstantiation but repaired the public scandal he had given and died reconciled to the Church.

The third big controversy was at the Reformation. Luther was the only one among the Reformers who still clung to the old Catholic tradition. Though he subjected it to much misrepresentation, he defended it most tenaciously. He was diametrically opposed by Zwingli, who reduced the Eucharist to an empty symbol. Calvin tried to reconcile Luther and Zwingli by teaching that at the moment of reception the efficacy of Christ’s body and blood is communicated from heaven to the souls of the predestined and spiritually nourishes them.

When Photius started the Greek Schism in 869, he still believed in the Real Presence. The Greeks always believed in it. They repeated it at the reunion councils in 1274 at Lyons and 1439 at Florence. Therefore it is evident that the Catholic doctrine must be older than the Eastern Schism of Photius.

In the fifth century the Nestorians and Monophysites broke away from Rome. In their literature and liturgical books they preserved their faith in the Eucharist and the Real Presence, but they had difficulty because of their denial that in Christ there are two natures and one Person. Thus the Catholic dogma is at least as old as the Council of Ephesus in 431. To establish that the truth goes back beyond that time one need only examine the oldest liturgies of the Mass and the evidence of the Roman catacombs. In that way we find ourselves back in the days of the apostles themselves.

The three controversies just mentioned helped considerably to formulate the dogma of transubstantiation. The term itself, transubstantiation, seems to have been first used by Hildebert of Tours about 1079. Other theologians, such as Stephen of Autun (d. 1139), Gaufred (d. 1188), and Peter of Blois (d. 1200), also used it. Lateran IV in 1215 and the Council of Lyons in 1274 adopted the same expression, the latter being in the Profession Faith proposed to the Greek Emperor, Michael Palaeologus.

Trent was, of course, the council which was summoned specially to refute the errors of the Reformation. After affirming the Real Presence of Christ, the reason for it, and the preeminence of the Eucharist over other sacraments, the council defined the following on October 11, 1551: “Because Christ our Redeemer said it was truly his body that he was offering under the species of bread, it has always been the conviction of the Church, and this holy council now declares that, by the consecration of the bread and wine a change takes place in which the whole substance of bread is changed into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord, and the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the Holy Catholic Church fittingly and properly names transubstantiation.”

The following canon also was promulgated by the Council: “If anyone says that the substance of bread and wine remain in the holy sacrament of the Eucharist together with the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, and denies that wonderful and extraordinary change of the whole substance of the bread into Christ’s body and the whole substance of the wine into his blood while only the species of bread and wine remain, a change which the Catholic Church has most fittingly called transubstantiation, let him be anathema.”

Let us try to analyze this idea. We speak of the conversion of bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood. What do we mean by conversion? We mean the transition of one thing into another in some.aspect of being. It is more than mere change. In mere change one of the two extremes may be expressed negatively, as for example the change of day and night. Night is simply the absence of the light of day. The starting point is positive, while the target, so to speak, is negative. It can be the other way about when we talk of the change of night into day.

Conversion is more than this. It requires two positive extremes. They must be related to each other as thing to thing. For true conversion one thing must run into another thing. It is not just a question of water, for example, changing into steam. Moreover, these two things must be so intimately connected with each other that the last extreme, let us call it the target of the conversion, begins to be only as the first, the starting point, ceases to be. An example of this is the conversion of water into wine at Cana. This is far more radical than the change of water into steam.

A third element is required. There must be something which unites the starting point to the target, one extreme to the other, the thing which is changed to that into which it is changed. At Cana, what was formerly water is now wine. Conversion must not be a kind of sleight of hand, a conjuring trick, an illusion. The target, the element into which the change takes place, must newly exist in some way just as a starting point. The thing which is changed must in some manner really cease to exist. Thus at Cana wine did not exist before in those containers, but it came to exist. Water did exist, but it ceased to exist. But the water was not annihilated. If the water had been annihilated, there would not have been a change but a new creation. We have conversion when a thing which really existed in substance acquires an altogether new and previously non-existing mode of being.

Transubstantiation is unique. It is not a simple conversion. It is a substantial conversion. One thing is substantially or essentially converted into another thing. There is no question here of a merely accidental conversion, like water into steam. Nor is it something like the metamorphosis of insects or the transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor. There is no other change exactly like transubstantiation. In transubstantiation only the substance is converted into another substance, while the accidents remain the same. At Cana substance was changed into substance, but the accidents of water were changed also into the accidents of wine.

The doctrine of the Real Presence is necessarily contained in the doctrine of transubstantiation, but the doctrine of transubstantiation is not necessarily contained in the Real Presence. Christ could become really present without transubstantiation taking place, but we know that this is not what happened because of Christ’s own words at the Last Supper. He did not say, “This bread is my body,” but simply, “This is my body.” Those words indicated a complete change of the entire substance of bread into the entire substance of Christ. The word “this” indicated the whole of what Christ held in his hand. His words were so phrased as to indicate that the subject of the sentence, “this,” and the predicate, “my body,” are identical. As soon as the sentence was complete, the substance of the bread was no longer present. Christ’s body was present under the outward appearances of bread. The words of institution at the Last Supper were at the same time the words of transubstantiation. If Christ had wished the bread to be a kind of sacramental receptacle of his body, he would surely have used other words, for example, “This bread is my body” or “This contains my body.”

The revealed doctrine expressed by the term transubstantiation is in no way conditioned by the scholastic system of philosophy. Any philosophy that distinguishes adequately between the appearances of a thing and the thing itself may be harmonized with the doctrine of transubstantiation. Right thinking demands that one makes a distinction between what a thing is and what it has. That is part of ordinary common speaking. we say, for example, that this is iron, but it maybe cold, hot, black, red, white, solid, liquid, or vapor. The qualities, actions, and reactions do not exist in themselves; they are in something. We call that something the substance. It makes a thing what it is. When we talk about transubstantiation we are using the word substance in that sense. It is unfair for people who do not want to accept this doctrine to invent their own definition of substance and then to tell us we are wrong.

All that substance sustains, the things which inhere in it, we call by the technical name of accidents. We cannot touch, see, taste, feel, measure, analyze, smell, or otherwise directly experience substance. Only by knowing the accidents do we know it. So we sometimes call the accidents the appearances.

At Mass the priest does exactly what Christ told him to do at the Last Supper. He does not say, “This is Christ’s body,” but “This is my body.” These words produce the whole substance of Christ’s body. In the same way the words of consecration produce the whole substance of Christ’s blood. They are Christ’s body and blood, as they are now living in heaven. There, in heaven, his body and blood are united with his soul and Godhead. The accidents or appearances of his human body are in heaven too. They are present, therefore, in the Holy Eucharist. For want of a better term we speak of them as following the substance. By the words of consecration the substance is immediately and directly produced. The personal accidents of Christ, his appearances, are there by what the theologians call “natural concomitance.”

Every raindrop that falls contains the whole substance of water. That same entire substance is present in the tiniest particle of steam which comes from the kettle on the hob. The entire substance of Christ is present in each consecrated host, in a chalice of consecrated wine, in each crumb that falls off the host, and in each drop that is detached from the wine.

But we must not imagine that Christ is compressed into the dimensions of the tiny, circular wafer or a grape. No, the whole Christ is present in the way proper to substance. He can be neither touched nor seen. His shape and his dimensions are there, but they are there in the same way as substance is there, beyond the reach of our senses.

When the priest at Mass, obeying Christ, speaks the words of consecration, a change takes place. The substance of bread and the substance of wine are changed by God’s power into the substance of Christ’s body and the substance of his blood. The change is entire. Nothing of the substance of bread remains, nothing of the substance of wine. Neither is annihilated; both are simply changed.

The appearances of bread and wine remain. We know that by our senses. We can see, touch, and taste them. We digest them when we receive Communion. After the consecration they exist by God’s power. Nothing in the natural order supports them because their own proper substance is gone. It has been changed into Christ’s substance. They do not inhere in the substance of Christ, which is now really present. It is not strictly true to say that Christ in the Eucharist looks like bread and wine. It is the appearances of bread and wine that look like bread and wine. The same God who originally gave the substance of bread power to support its appearance keeps those appearances in being by supporting them himself.

Christ is present as substance. That is the key to a right understanding of this mystery. He does not have to leave heaven to come to us in Communion. There is no question of his hopping from host to host or rushing from church to church to be present in each for a little while. When we receive Communion we are not given a particle of Christ’s body of the same dimension as the small wafer the priest puts on our tongue. Those who imagine otherwise have failed to g.asp the meaning of substantial presence.

Many of the Fathers of the Church warned the faithful not to be satisfied with the senses which announce the properties of bread and wine.

Cyril of Jerusalem (d. 386) said, “Now that you have had this teaching and are imbued with surest belief that what seems to be bread is not bread, though it has the taste, but Christ’s body, and what seems to be wine is not wine, even if it appears so to the taste, but Christ’s blood.”

John Chrystostom (d. 407) said, “It is not the man who is responsible for the offerings becoming Christ’s body and blood, it is Christ himself, who is crucified for us. The standing figure [at Mass] belongs to the priest who speaks these words, the power and the grace belong to God. ‘This is my body,’ he says. This sentence transforms the offerings.”

Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444) wrote, “He used a demonstrative mode of speech, `This is my body’ and ‘This is my blood,’ to prevent your thinking that what is seen is a figure; on the contrary what has truly been offered is transformed in a hidden way by the all-powerful God into Christ’s body and blood. When we have become partakers of Christ’s body and blood, we receive the living giving, sanctifying power of Christ.”

Berengarius, recanting from his error, made on oath a profession of faith to Pope Gregory VII:

“With my heart I believe, with my mouth I acknowledge, that the mystery of the sacred prayer and our Redeemer’s words are responsible for a substantial change in the bread and wine, which are put on the altar, into Jesus Christ our Lord’s own, true, life-giving flesh and blood. I acknowledge, too, that they are, after consecration, Christ’s true body which was born of the Virgin, which hung on the cross as an offering for the salvation of the world and which is seated at the right hand of the Father, and Christ’s true blood which flowed out of his side: they are not such simply because of the sacrament’s symbolism and power, but as constituted by nature and as true substances.”

It may be as well to quote here the explanation of a leading modern theologian. Louis Bouyer, a priest who was formerly a Lutheran minister and has for many years been one of the leading Catholic lecturers and writers, says, “Transubstantiation is a name given in the Church . . . Although Tertullian had already used the word, Christian antiquity preferred the Greek expression metabole, translated into Latin by conversio.

“The word transubstantiation came to be used by preference during the Middle Ages, both as a reaction against certain theologians like Ratramus, who tended to see in the Eucharist only a virtual and not a real presence of the body and blood of the Lord, and against others like Paschasius Radbertus, who expressed his presence as if it were a question of a material and sensible one.

“To speak of transubstantiation comes down then to stating that it is indeed the very reality of the body of Christ that we have on the altar after the consecration, yet in a way inaccessible to the senses and in such a manner that it is neither multiplied by the multiplicity of the species, nor divided in anyway by their division, nor passible [subject to suffering] in anyway whatsoever.

In conclusion we cannot do better than quote the words of the Imitation of Christ: “You must beware of curious and useless searching into this most profound sacrament. He who is a scrutineer of majesty will be overwhelmed by its glory.”