The True Ten Commandments

Last fall the news focused on a judicial building in Alabama with its display in granite of the Ten Commandments, sponsored and installed by Alabama’s chief justice, Roy Moore. Judge Moore defied a ruling for its removal, and by year’s end both the monument and the judge were gone. Sincere Christians of all denominations and even some representatives of Judaism protested their removal, but in vain.

The Universal Significance of the Decalogue

The Ten Commandments, or Decalogue, are rightly revered and practiced by those of Judeo-Christian heritage. But Catholics maintain that the Decalogue can be honored by all peoples and citizens of a country because it is natural law and not just revealed law. Therefore, there is universal application of the requirements of these commandments, regardless of religious affiliation. The Decalogue can hold a fundamental place along with the opening words of the U. S. Declaration of Independence, which also makes an appeal to natural law: “We hold these truths to be self evident . . .”

The Church Father Irenaeus writes of the natural law of the Decalogue: “Their fathers were righteous: they had the power of the Decalogue implanted in their hearts and in their souls. . . . Through the Decalogue he [God] prepared man for friendship with himself and for harmony with his neighbor” (Treatise against Heresies).

The Ten Commandments in the Bible

The heritage of the Old and New Testaments is our primary and truest source for reception of the Decalogue. In both the books of the New Testament, Revelation and Hebrews, the preciousness of these tablets are reconfirmed. In the vision of John (Rev. 11:19) there was seen in the heavenly temple the Ark of the Covenant, within which, as tradition holds (Heb. 9:4), were the tablets of the covenant.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms the greatness of the Decalogue and its demonstration of the natural law: “The ‘deposit’ of Christian moral teaching has been handed on . . . alongside the Creed and the Our Father the basis for this catechesis has traditionally been the Decalogue which sets out the principles of moral life valid for all men” (CCC 2033).

And yet, as Catholics watched the monument being removed from the judicial building in Alabama, they may have observed in a close-up shot of the commandments that they were not the same ten nor the numerical arrangement they had learned in childhood. The courthouse rendition read:

- I am the Lord thy God, thou shalt have no other gods before me.

- Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.

- Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.

- Remember the Sabbath Day to keep it holy.

- Honor thy father and thy mother.

- Thou shalt not kill.

- Thou shalt not commit adultery.

- Thou shalt not steal.

- Thou shalt not bear false witness.

- Thou shalt not covet.

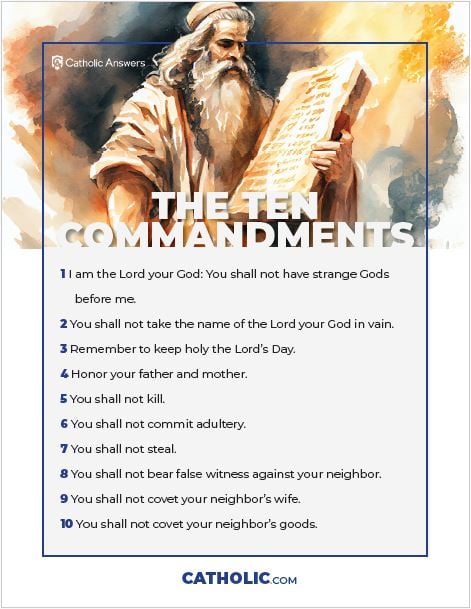

Whereas the Catechism’s traditional presentation of the commandments for memorization are:

- I am the Lord your God: You shall not have strange Gods before me.

- You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain.

- Remember to keep holy the Lord’s Day.

- Honor your father and mother.

- You shall not kill.

- You shall not commit adultery.

- You shall not steal.

- You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

- You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife.

- You shall not covet your neighbor’s goods.

Free Download | The Ten Commandments

The early Christian church, received this catechetical tradition from the Church Fathers, especially Augustine. He relied heavily on the Decalogue as presented by Moses in Deuteronomy 5. Thus, until the late Middle Ages, children memorized the commandments in the order as we still know it from the Catechism. Even after the Reformation, Lutherans and Catholics agreed on this enumeration and arrangement.

Calvin and other Reformers, relying more on Exodus 20 and its presentation of the Decalogue, and wanting to make a strike against the statuary and icons in the Catholic Church, enumerated the commandments in a different way. Based on this new sixteenth-century re-presentation of the Decalogue, many denominations in America now teach the commandments much as they were seen on the Alabama monument. Thus one can see a problem would be created if public squares or public schools were allowed to display the Ten Commandments: Whose version should prevail?

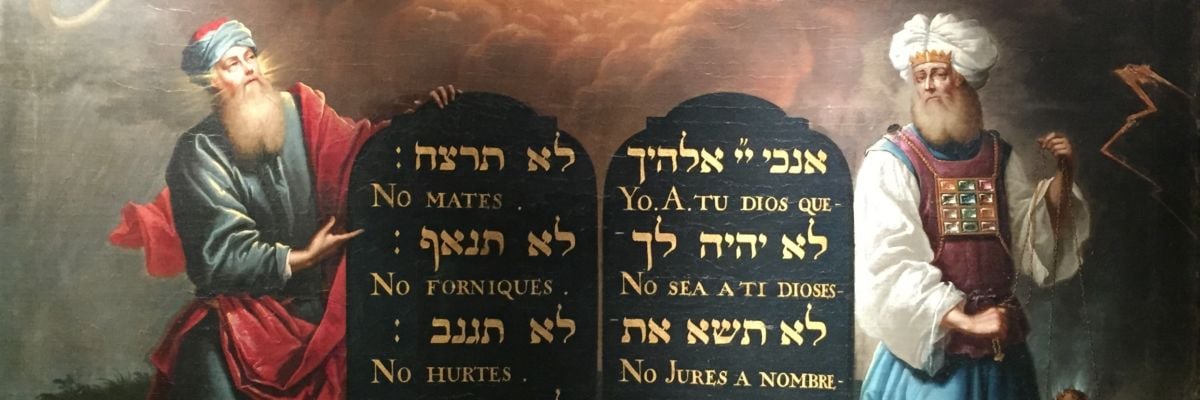

While Jewish versions of the commandments follow Exodus 20 primarily, their enumeration does not exactly follow that of the Reformers. The first commandment in Jewish life is usually the creedal statement of verse 2 of Exodus 20: “I am the Lord your God.” This affirmation of monotheism and loyalty corresponds to the famous “Shema” of Deuteronomy 6:4. The second commandment in Jewish faith encompasses both verses 3 and 4 against polytheism and the making of or worship of images of other deities or gods. It is only with the third commandment that there is correspondence to the Reform list. In all traditions the second through eighth commandments as listed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church basically correspond to one another. The divergence happens in the first and second commandments and then at the end in the ninth and tenth commandments.

In an attempt to find the most original Decalogue between Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, scholars have found that both decalogues are a mixture of older and newer traditions, as each book was being written in an earlier millennium. While some may argue that an earlier Decalogue should have primacy, others will argue, more correctly it seems to me, that the latest tradition encoded in sacred Scripture has primacy as the further development in understanding that God intended. In the commandment regarding keeping the Sabbath, the rationale for keeping it provided by Deuteronomy is seen by scholars to be more ancient than the one provided by Exodus, though both rationales are important (cf. Exodus 20:8–11 and Deuteronomy 5:12–15).

The Ten Commandments in Modern Context

Since both Exodus and Deuteronomy open in basic agreement on observing or remembering to keep holy the Sabbath, there is little controversy today between denominations on this commandment’s meaning that a special day of the week is to be kept holy. However, the Catechism emphasizes the Christian tradition that the special day to be kept holy is called the Lord’s Day (Latin, Dies Domini), which is Sunday, the day of Jesus’ resurrection. The early delineation of Sunday as the Lord’s Day is seen already in Revelation 1:10.

In contrast, the Decalogue’s presentation in Exodus shows an earlier cultural mindset in putting the wife and household objects as common possessions together under one command against covetousness in (Ex. 20:17). Moses, in separating the wife from household objects with a separate word for coveting in Deuteronomy 5:21, creates a new dignity for marriage, monogamy, and women that corresponds to the understanding reflected in the New Testament and in subsequent Church teaching (especially the writings of Pope John Paul II). Thus it seems to me the Christian tradition was correct in making the end of the Decalogue two separate commandments by following Deuteronomy 5.

Much ink has been spilled regarding the early verses of the Decalogue about monotheism and images. The command of monotheism produces little disagreement. But is there a separate commandment regarding images, or are the verses regarding images meant as an example of the practice of monotheism and therefore intimately part of the first commandment? Again our answer depends on which text we choose, Exodus or Deuteronomy, for there are syntax differences. Exodus 20:3 (“You shall have no other gods before me”) is a closed sentence and could be a complete commandment.

In Deuteronomy 5:7, the Hebrew construction is such that the wording is only the first part of what follows in the commandment, that no idol representing the deity be carved nor placed before the Lord God nor any such carved image be worshiped. In fact, we read verses 6–10 continuously, as one unit, before coming up for air.

In ancient Israel, the Lord God (Yahweh) was to receive exclusive worship (in a world full of the gods of other nations) and was not to be represented in images like other nations did for their deities. In fact, if one were ever to speak of an image of God, one could refer to how later rabbis said that God had already made such an image in mankind: “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (Gen. 1:27).

Thus the syntax of Exodus 20 can look like two commandments: prohibition of polytheism and prohibition of making carved images. But the syntax of Deuteronomy 5:7–11 shows one commandment, prohibition of idolatry (especially involving carved images that represent other gods or Yahweh). So Catholics are justified after Augustine (following Deuteronomy) in seeing a single commandment in the opening verses of the Decalogue. This, of course, affects the whole counting of the commandments up through the tenth commandment.

Was the prohibition of images in worship of Yahweh also a prohibition of any and all artistic images of other realities in the world or in places of worship? Obviously not. Moses ordered the making of the cherubim statues to flank the Ark of the Covenant in the Holy of Holies. Moses even had a bronze serpent fashioned in the desert for the healing of those bitten by serpents. The first commandment shows us that we are not to make an image of God or of other gods before God or in his presence (except the one image God himself fashioned: man and woman. We are the images of God who go before him in prayer and worship, because God has made us and called us. Thus we see the awesome dignity of the human person and each human life that God has created.).

Christians do make artistic representations of saintly heroes or heroines—such as Mary and the saints—to inspire admiration and imitation. Even Jesus in his human nature is portrayed in the suffering figure on the crucifix or as a statue of the Good Shepherd or some other earthly remembrance of his Incarnation. Such artistic renderings not only do not violate the first commandment, but they affirm more solidly the Incarnation, God’s presence and work in the material elements of this world, beginning with Jesus becoming flesh.

The Commandments in American Public Life

In our national consciousness, the distinction between admiring, imitating, or honoring someone and worshiping him is easily made (we hope) by Americans visiting the Lincoln or Jefferson memorials or Mt. Rushmore. The men honored in these places are national heroes. So why is it difficult for many to acknowledge Christians as making such a distinction with images of their heroes and heroines of faith, the saints of history worthy of admiring, imitating, and honoring?

Whose list of commandments shall prevail? We do not know the future but it seems that we will continue to see these two versions in the mixed religious scene of American life. It is worthwhile to note that the Church itself is not dogmatic about the numbering system one uses. But a good apology for the list Catholics have traditionally memorized, representing the most ancient of Christian traditions, is handy to have in the advancement of the moral truth for all humanity that these commandments represent.