The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that “Belief in the true Incarnation of the Son of God is the distinctive sign of Christian faith: ‘By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit which confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is of God’” (CCC 463, citing 1 John 4:2). Along with the Trinity—which the Incarnation revealed to humanity—the entrance of the Word into time and space is the core fact of Christianity. It is also the stumbling block that has often separated the orthodox from the heterodox, as the Christological battles of the early councils so clearly attest.

Although our separated brethren defend the Incarnation and affirm that Jesus Christ is truly God and truly man, my personal experience debating Fundamentalists indicates that what is apparently held is not always firmly grasped. This becomes clear when examining some of the Fundamentalist attacks made on various Catholic doctrines by looking into the heretical genealogy of the assumptions behind those assaults.

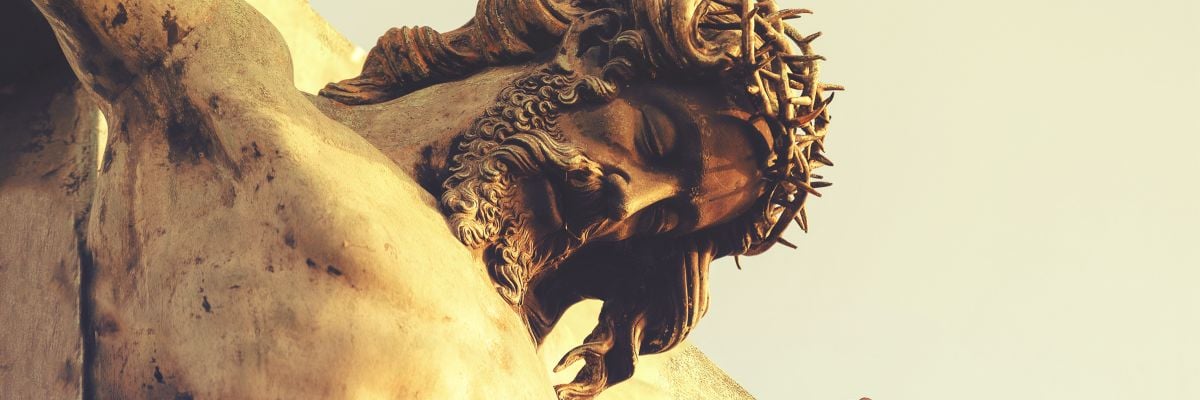

Images

Recently I visited an anti-Catholic site (www.jesus-is-lord.com) whose home page proclaimed in bold letters: “God HATES images. ANY kind of image. . . . It is idolatry to venerate images. We are not even supposed to make them.” This sums up the common Fundamentalist attitude towards the use of images to aid the believer in worshiping God. It is linked with a demand for stark simplicity in their meeting places. Fundamentalist services are noteworthy for lengthy sermons and impromptu prayers, led mostly by the pastor, while the congregation sits in an unadorned meeting place. The goal is freedom from distractions in order to focus on the sermon. There is a strong fear of idolatry, similar to the fear behind the Iconoclasm of the eighth and ninth centuries and the stripping of Catholic churches by the Reformers seven hundred years later.

The Catholic position is simple: If Jesus really is true God and true man, and if he has existed physically in this world, then he can be represented in visual arts. The Old Testament decrees against images were made when mankind was just beginning to understand who Yahweh was and how he related to humanity. The “fullness of time” had not yet been realized—humanity had much to learn before God would come as man and dwell among us. But with the Incarnation came big changes. The Catechism explains this beautifully:

“The sacred image, the liturgical icon, principally represents Christ. It cannot represent the invisible and incomprehensible God, but the Incarnation of the Son of God has ushered in a new ‘economy’ of images: Previously God, who has neither a body nor a face, absolutely could not be represented by an image. But now that he has made himself visible in the flesh and has lived with men, I can make an image of what I have seen of God . . . and contemplate the glory of the Lord, his face unveiled. . . . The veneration of sacred images is based on the mystery of the Incarnation of the Word of God. It is not contrary to the first commandment” (CCC 1159, 2141; see 1160).

For Fundamentalists, a visual aid is something placed between man and God, removing us further from a “personal relationship” with the Creator. Ironically, while God became man so we might know how to relate to him in a truly personal way, the Fundamentalist misses this by insisting on knowledge gained only through “spiritual” means, as though the humanity of the God-man has no effect on the entire person. “By avoiding the dangers of magic and idolatry on the one hand,” writes Thomas Howard, a former Evangelical, “Evangelicalism runs itself very near the shoals of Manichaeanism on the other—the view, that is, that pits the spiritual against the physical. . . . But by denying to the whole realm of Christian life and practice the principle that it allows in all the other realms of life, namely, the principle of symbolism and ceremony and imagery, it has, despite its loyalty to orthodox doctrine, managed to give a semi-Manichaean hue to the faith” (Evangelical Is Not Enough, 5).

Mother of God

The Blessed Virgin is always a prime target for Fundamentalist attacks, especially her title of Theotokos (“Mother of God“). James McCarthy, a former Catholic who now operates a ministry meant to “save” Catholics, writes in The Gospel According to Rome that “the Bible . . . never calls Mary the ‘Mother of God’ for a very simple reason: God has no mother. As someone has rightly said, just as Christ’s human nature had no father, so his divine nature had no mother. This Bible, therefore, rightly calls Mary the ‘mother of Jesus’ (John 2:1; Acts 1:14) but never the ‘Mother of God’” (190–191).

McCarthy’s statement illustrates the Fundamentalist practice of making damaging dichotomies where unity and balance should be maintained. The first problem is that mothers do not give birth to natures—they give birth to persons. A nature tells us “what” someone is (for example, human); a person is “who” that someone is (for example, Jesus). It is true that Jesus’ humanity comes from Mary and his divinity from the Father (CCC 503). But he is not partially divine and partially human, as McCarthy’s statement implies. To consider divinity and humanity as separate elements of Christ’s personhood implies inadequacy, since one part is required to fulfill the other. Such cannot be the case, for the God-man was completely perfect and whole in all ways (CCC 464, 483). It is this perfect wholeness, brought about by the hypostatic union (CCC 467–469), that the Fundamentalist either ignores or does not appreciate.

Secondly, it is true that God, being eternal, has no mother. However, “Emmanuel”—”God with us”—came to humanity in time and space, and his conduit into history was the womb of the Virgin Mary. God also never wore clothing, ate food, or went fishing—at least, not until he became man in the person of Jesus Christ.

Finally, the Bible does indeed call Mary the Mother of God. When the expecting Mary visited her cousin Elizabeth, also pregnant, Elizabeth’s baby, John the Baptist, leapt in her womb (Luke 1:41). Elizabeth exclaimed that Mary was “blessed” and that she was the “mother of my Lord” (Luke 1:43; also see Luke 1:35 where Mary’s child “will be called holy, the Son of God”).

The Fundamentalist error is similar to that of Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople in the 420s, who insisted on the Marian title Christotokos (“Mother of Christ”) instead of Theotokos. Nestorius’s teachings suggested that the two natures of Jesus are bound by a moral union only, not a hypostatic union. This implied the existence of two persons in Christ: Jesus the man and Jesus the divine Word. But Christ is only one person: the Incarnate Word (CCC 466). Unfortunately, in attempting to defend the person of Christ, Fundamentalists echo a heresy that undermines the unity of his person.

The Eucharist

An anti-Catholic pastor recently wrote to me declaring: “There is no room for ceremonial sacramental religion in the Word of God.” This highlights a key fact: Most Protestants believe a physical sign or act cannot achieve an inward effect or change. This is problematic because the promise of God—regeneration and spiritual empowerment—was realized and actualized in the outward, physical manifestation of grace that was Jesus Christ. “The saving work of [Christ’s] holy and sanctifying humanity is the sacrament of salvation, which is revealed and active in the Church’s sacraments” (CCC 774). Dislike of the sacraments can result from a failure to appreciate the consequences for the material realm of God becoming man. As tangible signs that God uses to effect the grace they signify, sacraments bring God’s grace to us in forms we can comprehend with our senses.

The Eucharist brings the Fundamentalist’s neo-Gnostic and Rationalistic tendencies to the surface. James McCarthy claims Fundamentalists judge the Catholic belief in the Real Presence false because “there is not even the slightest indication that either the bread or the wine changed at the Last Supper. The same is true at the Mass today. The bread and wine before and after the consecration look exactly alike. Furthermore, they smell, taste, and feel the same. In fact, all empirical evidence supports the interpretation that they do not change at all” (The Gospel According To Rome, 133).

This reliance on “empirical evidence” raises difficult questions for McCarthy’s own position. Since when does Christianity rest on scientific evidence? Where is the empirical evidence for the Virgin Birth? Angels? The Holy Spirit? Heaven? And where is the empirical proof that Jesus was completely God, completely man? If Jesus had given a tissue sample on the shores of Galilee, would the DNA have shown him to be God? Didn’t the people say, “Is not this Jesus, the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know? How does he now say, ‘I have come down from heaven’?” (John. 6:42).

The Fundamentalist stance of mocking the Eucharist while defending the Incarnation is inconsistent. G. K. Chesterton eloquently lamented this lack of logic:

“Heaven has descended into the world of matter; the supreme spiritual power is now operating by the machinery of matter, dealing miraculously with the bodies and souls of men. It blesses all the five senses. . . . It works through water or oil or bread or wine. . . . I cannot for the life of me understand why [a Protestant] does not see that the Incarnation is as much a part of that idea as the Mass. A Puritan may think it blasphemous that God should become a wafer. A Muslim thinks it blasphemous that God should become a workman of Galilee. . . . If it be profane that the miraculous should descend to the plan of matter, then certainly Catholicism is profane; and Protestantism is profane; and Christianity is profane. Of all human creeds and concepts, in that sense, Christianity is the most utterly profane. But why a man should accept a Creator who was a carpenter and then worry about holy water, . . . why he should accept the first and most stupendous part of the story of Heaven on Earth and then furiously deny a few small but obvious deductions from it—that is a thing I do not understand; I never could understand; I have come to the conclusion that I shall never understand” (“The Protestant Superstitions,” Collected Works, 3: 258–259).

Historically, the Fundamentalist dislike for the Eucharist is related to a number of divergent movements: Docetism, the Reformation, and Enlightenment-era rationalism. While differing in other ways, each of these movements had the same symbolic understanding of the Eucharist. Ignatius of Antioch, a disciple of the apostle John, condemned the Docetists for their refusal to accept the Real Presence, a stance based on their denial of Christ’s humanity: “They hold aloof from the Eucharist and from services of prayer, because they refuse to admit that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins” (Letter to the Smyrnaeans, 6:2). Docetists believed that only the spiritual realm is real; the physical realm is illusory and temporary, possessing little or no value.

Evangelical scholar Mark Noll admits this description fits Fundamentalism today. At the heart of Fundamentalism, Noll writes, is “a tendency toward a docetism in outlook and a gnosticism in method” (The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, 123). The more radical Reformers, such as Zwingli, apparently spurred on by a hatred for the sacramental and sacerdotal order, insisted upon a symbolic meaning only.

Fundamentalism, historically and theologically, is also a stepchild of the Enlightenment. The desire during the nineteenth century to explain the Bible “scientifically” led to the use of methods of Scriptural interpretation that resulted in the rigid theology so evident in the writings of anti-Catholics today.

Salvation

Because Fundamentalists either ignore or misjudge the importance of the physical realm in spiritual matters, they often strongly object to how Catholics express the doctrine of salvation. This is reflected in the classical Protestant emphasis on “faith alone” (sola fide). Most Fundamentalist groups emphasize salvation is a finished work. It is acquired, they claim, through a once-for-all-time “acceptance” of Jesus Christ as “personal Lord and Savior.” Once again we see is a division between the spiritual and physical realms: You are saved by an act of purely mental assent (which is spiritual) and then perform good works (which are physical).

Since the Catholic Church has always insisted that good works, animated by grace, are necessary for one’s growth into salvation (cf. Phil. 2:12), anti-Catholics are convinced this is evidence of Catholic “apostasy.” Many point to Christ’s words on the cross: “It is finished.” “See!” they exclaim, “Christ’s salvific work is finished! We cannot add to it!”

But would they teach that Christ could have remained in the grave and our salvation would have still been guaranteed? And if our salvation were finished so that there was nothing left for us to do, why do we still need to “believe” and “ask Jesus into our hearts,” as the Fundamentalist’s own strategies insist?

The deeper issue is a failure to recognize that Christ’s salvific work, while culminating in his death and Resurrection, did not start at Golgotha. Rather, the entrance of the Word into time and space was the embodiment—literally—of salvation. The Word took on flesh because God desired to save the entire person: body and soul. This will be finally and fully realized in the resurrection of the body.

Yet it appears many Fundamentalists forget the person is more than just a soul and end up with the same neo-Gnostic perspective evident in their criticism of the Eucharist. And there is no doubt the two are related. If the body is secondary, even non-essential, the idea of eating Christ in what appears to be bread and wine becomes even more absurd. But if it is understood that the body expresses the interior reality of a person, then our physical existence takes on a sacred and substantial meaning.

Christ taught that good works are not only the result of being saved, but signify actual growth in charity, the virtue without which we cannot enter heaven. This is shown in the parable of the goats and the sheep (Matt. 25:32ff). The words of Christ show us how closely bound are acts of charity with our salvation: “Then he will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me.’ And they will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life” (Matt. 25:45–46). Paul described the same reality, writing that it is “faith working through love” (Gal. 5:6) that will dictate where we spend eternity. The Incarnation shows us that salvation comes to where people are, in all their physical and spiritual despair, bringing them healing and hope that can be made evident to their senses through the sacraments and Church.

As someone who was raised in the Fundamentalist belief system, I would describe it as a worldview that gives lip service to major elements of the Christian faith but will not—or perhaps cannot—consider the awesome implications of those truths. As Thomas Howard indicates, there is such a fear of idolatry that true worship suffers; such a distrust of the human mind that theological examination is spurned; such a discomfort with the body that one’s humanity is stifled; such a dislike of the mystical that mystery withers and dies.

At the heart of this perspective is an inability to contemplate many implications of the Incarnation: what is means that God would enter history, would grow as a man, would eat, drink and sleep, and would finally, in horrific fashion, die. The Fundamentalists’ bias keeps them from seeing more fully what the Resurrection means for the Christian and how the promise of a glorified body points to the beauty and value of the body in the eyes of God. The Catechism teaches us that “Christ enables us to live in him all that he himself lived, and he lives it in us. ‘By his Incarnation, he, the Son of God, has in a certain way united himself with each man’” (CCC 521).

This beautiful truth of God’s union with us by his becoming flesh is something that we Catholics need to be able to explain to anti-Catholics. We must seek to demonstrate that there is a wider and deeper meaning to the Incarnation: the calling of man by the God-man to “become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4).