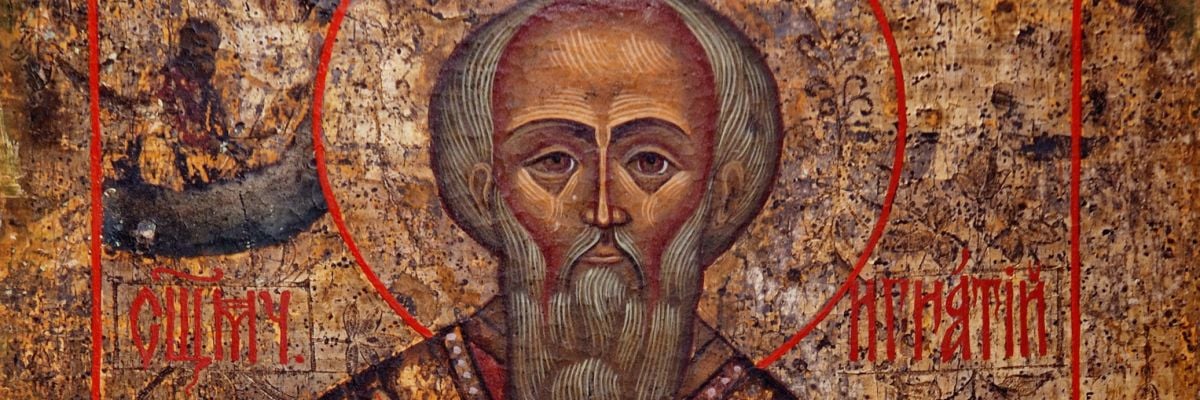

Some time around the year A.D. 107, a short, sharp persecution of the Church of Christ resulted in the arrest of the bishop of Antioch in Syria. His name was Ignatius. According to one of the harsh penal practices of the Roman Empire of the day, the good bishop was condemned to be delivered up to wild beasts in the arena in the capital city. The insatiable public appetite for bloody spectacle meant a chronically short supply of victims; prisoners were thus sent off to Rome to help fill the need.

So it was that the second bishop of Antioch was sent off to Rome as a condemned prisoner. According to Church historian Eusebius (260-340), Ignatius had been bishop in Antioch for nearly forty years. This means he must have been named bishop of the Church there while some of the original apostles were still alive and preaching. Ignatius was closer to Jesus’ crucifixion than we are to World War I.

Escorted by a detachment of Roman soldiers, Ignatius was conducted first by land from Syria across Asia Minor (modern Turkey). In a letter sent ahead to the Church in Rome, he described his ardent wish to imitate the passion of Christ through his own coming martyrdom in the Colosseum. He warned Christians in Rome not to interfere or try to save him. He spoke of his conflicts with his military escort and of their casual cruelties; he described his guards as “ten leopards.” The discipline of the march cannot have been too onerous, though, since Ignatius was able to receive delegations of visitors from local churches along the way.

In Smyrna (modern Izmir), Ignatius met not only with the bishop of that city, well known to history as Polycarp, who would be martyred in 156, but also with delegations from the neighboring cities of Ephesus, Magnesia, and Tralles; each delegation was headed by the local bishop.

In addition to his letter to Rome, Ignatius wrote letters to the Christians in each of the cities following its delegation’s visit to the shackled bishop-prisoner as he passed through. It is as a result of these letters that Ignatius is known to us today. Establishing these letters, written in Greek, as authentic, as genuinely coming down to us from the first decade of the second century, was one of the triumphs of British Protestant scholarship of the nineteenth century. Without them, Ignatius might have remained as obscure as many another ancient bishop, no more than a name.

Conducted on to the Greek city of Troas on the Aegean Sea, Ignatius wrote yet another letter to the Church at Smyrna, through which he had passed, as well as to its bishop, Polycarp. Finally, he wrote a letter to the Philadelphians, who had dispatched two deacons after him and who had overtaken his party at Troas.

Shortly after writing these seven letters to Churches in Asia Minor, Ignatius was taken aboard ship; the remainder of his journey to Italy was by sea. History records that he won his longed-for martyrdom in the Roman amphitheater during the reign of the Roman Emperor Trajan (98-117).

The seven letters he left behind afford us a precious and remarkable picture of just what the Church was like not two full generations after issuing from the side of Jesus Christ on the cross (and then, of course, being initially described in the Acts of the Apostles).

Ignatius’s tenure as a Church leader almost exactly spanned the transition period between the end of the first Christian generation and the beginning of the third; thus, his witness about the nature of the Church of his day is of fundamental importance.

What was the Church like around 107? First, the Church had already spread far and wide since the days of the apostles. Ignatius was conducted over a good part of what is modern Turkey, encountering local churches in most major towns. At the head of each of these churches there was a principal leader called a “bishop” the Greek word was episkopos, meaning “overseer.” This geographical spread of local churches, each headed by a bishop, is obvious from the fact that Ignatius was met by delegations headed by bishops coming from each sizable town along the route.

That Ignatius was met by “official” delegations indicates that these local churches were in close touch with one another. They did not see themselves as independent, self-governing “congregations” of like-minded people; they saw themselves as linked together in the one Body of Christ according to a firmly established and well-understood system, even though they were geographically separated.

The apparent solidarity with which they all turned out to honor a prisoner being led to martyrdom, who also happened to be the bishop of Antioch, tells us something about the respect in which that office was held. Antioch was to become, of course, one of the great patriarchal bishoprics of the Church of antiquity, along with Alexandria and Rome-and, later, Constantinople. By the turn of the first century, the bishop of Antioch was greatly respected, if not revered, because of his office, if we judge by Ignatius’s reception.

The letters of Ignatius are clear about the role which the bishop, or “overseer,” held in the early Church; the modern reader may even be startled at the degree to which these letters exalt the role of the bishop.

“It is essential to act in no way without the bishop,” Ignatius wrote to the Trallians. “Obey the bishop as if he were Jesus Christ” (2:2, 1). “Do nothing apart from the bishop,” he wrote to the Philadelphians (7:2). To the Smyrnaeans he gave the same advice: “You should all follow the bishop as Jesus Christ did the Father . . . Nobody must do anything that has to do with the Church without the bishop’s approval” (8:1).

It is obvious that the apostles appointed others besides themselves to offices in the Church. Peter and the other apostles at Jerusalem quickly decided to appoint deacons to assist them (cf. Acts 6:1-6). Paul similarly placed someone in authority in the churches that he founded (Acts 14:23, 2Tim. 1:6). More than just being “named,” however, these appointees were dedicated by means of a religious rite-the laying on of hands-either by those who already had authority conferred on them by Christ (the apostles) or by those on whom they had conferred authority in turn by the laying on of hands. These rites were what today we call sacramental ordinations.

For a period of time in the early Church there was no settled terminology for these ordained officers or ministers. Paul spoke of “bishops and deacons” (Phil. 1:1), though he also mentions other offices such as “apostles,” “prophets,” and “teachers” (1 Cor. 12:29). James spoke of “elders” (Jas. 5:14). In the Acts of the Apostles, we hear many times of “elders,” also translated “presbyters” (e.g., Acts 11:30). Sometimes the designations “bishop” and “elder” were used interchangeably.

By the second half of the first century a consistent terminology to describe these offices in the Church had become fairly fixed. In the letters of Ignatius it is clear that leadership in the Christian community is exercised by an order of “bishops, presbyters, and deacons” (Trallians 3:2, Polycarp 6:1). Of these designations, “bishop,” from the Greek episkopos, was applied to the highest officer in each local church. “Presbyter,” from the Greek presbyteros, meaning “elder,” and “deacon,” from the Greekdiakonos, meaning “servant” or “minister,” were applied to lesser officers. Henceforth these were the the terms for these offices in an “institutional” or “hierarchical” Church.

The term “priest” (Greek hierus) was not often used at first for the Christian presbyter. This is explained by the need to distinguish the Christian priests from the Jewish priests who were still functioning up to the time of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Romans in the year 70. Thereafter the use of the word “priest” for those ordained in Christ became more and more common.

Ignatius-who, as we have noted, was appointed to head the local church at Antioch while some of the original apostles were still alive-did not know of any such thing as a “church” which was merely an assemblage of like-minded people who had come together believing themselves to have been moved by the Spirit. The early Christians were moved by the Spirit to join the Church, of course, but they were moved to join an established, visible, institutional, sacerdotal, and hierarchical Church, which was the only kind of Church Ignatius would have recognized as the Church.

It was for this visible, institutional, sacerdotal, and hierarchical Church-an entity dispensing both the word and sacraments of Jesus-that this early bishop-martyr was willing to give himself up to wild beasts in the arena. He wrote to Polycarp (the words were also meant for the latter’s entire flock in Smyrna): “Pay attention to the bishop so that God will pay attention to you. I give my life as a sacrifice (poor as it is) for those who are obedient to the bishop, the presbyters, and the deacons” (6:1). To the Trallians he wrote: “You cannot have a church without these” (3:2).

Ignatius certainly recognized that (in one of today’s popular but imprecise formulations) “the people are the Church.” His letters were intended to teach, admonish, exhort, and encourage nobody else but “the people.” But he also understood that each one of “the people” entered the Church through a sacred rite administered by and in the name of the Church, baptism, and that thereafter they belonged to a group in which the bishop, in certain respects and for certain purposes, resembled the father of a family, or a “monarch” more than he resembled any of the kinds of democratically elected leaders we encounter today.

In what respects and for what purposes did the bishop resemble a “monarch”? Since Jesus came into the world to save us from our sins, sanctify us with his Spirit, and lead us to heaven, how can we imagine that he would saddle us with anything like a monarchical bishop, who, in what pertained to Christ’s truth and to our salvation, had to be obeyed? How can we imagine this, when Jesus taught that among his followers the leaders would have to be servants of the others? “Whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all” (Mark 10:44).

The answers to these questions about why Jesus established an institutional and hierarchical Church are implicit in his reason for founding any Church at all. Jesus wanted to preserve and perpetuate his teaching, the truths about God that he came into the world to proclaim, and to provide to those whom he had saved the sacramental means to share in his divine life. In order to insure the latter, in particular, Jesus had to establish within the community of his followers the power to re-present the sacrifice of the cross by which he had saved them.

To make his truths known, Jesus could have committed his teachings to writing, though he chose not to do so. The only time Jesus wrote anything was when the woman was caught in adultery: “Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground” (John 8:6). It is amazing that some Christians have been able to imagine that a Savior who never wrote anything down at all would found a religion based entirely on a book! We must remember that, prior to the invention of printing in the fifteenth century, books of any kind had to be copied by hand and were prohibitively expensive; people simply did not have the same access to the printed word that we have had for the last five centuries.

Simply committing his teachings to writing was not the best means for preserving and perpetuating them. Committing them into the hands of living men, divinely guided and protected, charged with faithfully handing them down in the community, was a better means of preserving and perpetuating them, and that is what Jesus did.

The historical fact is indisputable: Jesus chose to perpetuate both his teachings and his divine life in this world by committing them to the care of living men, the apostles. He gave them the power and responsibility of doing both- along with the ability to hand on the power given to them to successors. The apostles and their successors were given the power to perpetuate the continuing sacramental presence of Jesus in this world, as well as to teach what Jesus had taught them and to correct whatever errors might creep in to the minds of some Church members.

If Jesus thus confided this twofold power to a special class of men, he logically had to grant to the same men the authority to order the affairs of the community. So it was that the apostles and their successors, who came to be called bishops, were given the threefold power to teach, sanctify, and rule within the Church (as a later age concisely described the role and functions of bishops).

We see in the letters of Ignatius the whole Church system for carrying out the mission Jesus gave the apostles already firmly established and functioning by the end of the first century. Ignatius wrote no more than a long lifetime after the Crucifixion. In his letters he made frequent reference to teachings that all Christians were expected to accept as having come from Christ himself. In his letter to the Smyrnaeans, he even provided a remarkable yet concise summary of the fundamentals of the faith.

What was required was to have “unshakable faith,” he wrote, “in the cross of the Lord Jesus Christ . . . On the human side, he was sprung from David’s line, Son of God according to God’s will and power, actually born of a virgin, baptized by John that all righteousness might be fulfilled by him, and . . . crucified for us in the flesh under Pontius Pilate and Herod the Tetrarch. We are part of his fruit which grew out of his most blessed Passion . . . By his resurrection, he raised a standard to rally his saints and faithful forever, whether Jews or Gentiles, in one body of his Church. It was for our sakes that he suffered all this, to save us” (1:1-2).

Thus was the faith taught around 170 by one of the official teachers in the Church, the bishop of Antioch. There can be no doubt that this summary of the faith accords with the faith derived from the New Testament on the one hand and, on the other, with the creeds and other authentic statements of the faith formulated in later ages by the Church of Christ with the special assistance of the Holy Spirit.

One of the things Ignatius was most insistent on was the position of the monarchical bishop. He held to this because he saw so clearly the need for Church unity, which was achieved and guaranteed by the bishop. Ignatius congratulated the Ephesians on being united to their bishop just as the Church was united to Jesus Christ “and Jesus Christ to the Father. This is how unity and harmony come to prevail everywhere. Make no mistake about it. If anyone is not inside the sanctuary, he lacks God’s bread” (5:1-2). “God’s bread,” Ignatius wrote to the Romans, was nothing else than “the flesh of Christ” (7:3).

To the Smyrnaeans he wrote that they should only “regard that Eucharist as valid which is celebrated either by the bishop or by someone he authorizes” (8:2)-which tells us that, already at this early date, the bishops were “authorizing” others, were sharing a measure of the authority handed down to them from Christ with priests “authorized” to celebrate the Eucharist. Similarly, “without the bishops’ supervision, no baptisms [were] permitted” (ibid.).

The fruit of all this, for Ignatius, was the personal holiness and uprightness of conduct that was supposed to mark the follower of Christ. “We have not only to be called Christians,” he declared to the Magnesians, “but to be Christians” (4:1).

To the Ephesians he summarized the way Christians were to act in order to demonstrate that the spirit of the gospel had indeed been handed down in the Church: “Keep on praying for others . . . for there is a chance of their being converted and getting to God. Let them learn from you at least by your actions. Return their bad temper with gentleness, their boasts with humility, their abuse with prayer. In the face of their error, be steadfast in the faith. Return their violence with mildness and do not be intent on getting your own back. By our patience let us show we are their brothers, intent on imitating the Lord” (10:1-3).

We can confidently assert that the Church described in these letters was definitely “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic.” This Church possessed, in other words, the four marks or characteristics of the true Church that were later to be so concisely summed up in the Nicene Creed. At every Sunday and holy day Mass since time immemorial, Catholics have proudly professed belief in these four traditional “notes” or “marks” of the true Church of Christ. Catholics profess this belief by reciting the Nicene Creed, which issued from the Council of Nicaea (325) and was modified by the Council of Constantinople (381). These two great councils were held over two centuries after the events we have been considering. The words of the later Nicene Creed apply perfectly to this earlier period. There can be little doubt that the Church of Ignatius possessed all four of the characteristics specified by the Creed.

In accord with sacred Scripture, Catholic teaching has maintained that Jesus founded a specific Church into which all his followers were to be gathered. The Second Vatican Council stated, “The Lord Jesus poured forth the Spirit whom he had promised and through whom he called and gathered together the people of the New Covenant, which is the Church. . . . As the Apostle teaches us: ‘There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope of your calling; one Lord, one faith, one baptism’ (Eph. 4:4-5).” Vatican II goes on to describe this Church established by Jesus Christ as “God’s only flock . . . this one and only Church of God” (Decree on Ecumenism [Unitatis Redintegratio] 2, 3).

Ignatius’s letters reveal his understanding of that same “one and only Church of God.” His emphasis on the central role of the bishop in each local Church, for example, stemmed from his conviction that the bishop was the center of unity in the Church, guaranteeing that it would remain “one.” Ignatius wrote to the Philadelphians that there was only “one flesh of our Lord, Jesus Christ, and one cup of his blood that makes us one, and one altar, just as there is one bishop along with the presbyters and the deacons” (4:1). The unity of Christians was, in other words, a function of the unity of the Church to which they belonged, and that Church unity was guaranteed by the bishop of each local Church.

Similarly, Ignatius considered the Church to be holy. This was the case because it was in the Church that “God’s bread, which is the flesh of Christ” (Rom. 7:3), was present. Ignatius recognized that the Eucharist, celebrated within the Church, made Christians one. He believed that the faithful were gathered together to obtain a share of God’s grace through the sacrament of the Eucharist. He counseled the Ephesians “to gather together more frequently to celebrate God’s Eucharist.” He believed that it was by this more frequent Communion in the Church that “Satan’s powers [are] overthrown and his destructiveness . . . undone” (13:1) and the members of the holy Church brought closer to God in holiness.

Looking at the catholic, or “universal,” character of the Church as described by Ignatius, we find him remarking to the Ephesians that bishops continued to be “appointed the world over” (3:2), as, indeed, had been true in the time of Paul (Col. 1:6). In his letter to the Smyrnaeans Ignatius went on to employ a phrase whose first surviving use in Christian writings occurs here, a phrase that marks this letter as one of the most significant documents of the early Church. If Ignatius had written nothing but this one letter, he would remain a uniquely important witness to the nature of the Church founded by Christ.

The phrase which Ignatius employed in his letter to the Smyrnaeans was the name by which the Church of Christ had already become known: the “Catholic Church.” Ignatius wrote: “When the bishop is present, there let the congregation gather, just as where Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church” (8:2). This is the first surviving mention in Christian literature of the name, “the Catholic Church,” the name which the Council of Constantinople (381) would later employ in the Nicene Creed to designate the entity for which that Council was speaking.

According to the New Testament, it was in Antioch that the followers of Jesus Christ first came to be called “Christians” (Acts 11:26). When it came to the name of the community into which these Christians were gathered, they used another name, a name first recorded for posterity by the second bishop of that same Antioch.

No major entity known to history has ever been called “the Christian Church.” This term only came into use recently by people unwilling to concede that the Catholic Church-that is, the visible, historic community of professing Christians subject in their place of residence to a local bishop in communion with the bishop of Rome-is the organic successor Church to the one undivided Christian body. It was that body to which Ignatius belonged in the first century and which he styled “the Catholic Church,” undoubtedly following a usage already long established in his day.

In the New Testament the community of Christ’s disciples incorporated into him through baptism and the Eucharist was called simply “the Church.” From the time that any other adjective was applied to the noun “Church,” though, the term was derived not from the name of the divine Founder of this Church,but rather from one of its special characteristics: its catholicity. This body was the one, unique, saving body for everyone, everywhere, as distinguished from the partial or even counterfeit groups or sects that, already in New Testament times (1 John 2:19), were springing up in opposition to the true Church. They have not ceased to spring up in every age since.

These “protesting” splinter groups are usually offshoots from the true Church. They are, characteristically, self-established bodies or communities, while the true Church remains Christ-established. The name “Catholic Church” thus also has meant the one, true Church as distinguished from the sects separated from her.

Not surprisingly, the name “Catholic Church” caught on, and it has been employed down to our own day; there never has been a time when the one true Church, the real one, did not need to be distinguished from the many churches, communities, and sects claiming, with greater or lesser plausibility, to be “the Church.”

Already in the generation following that of Ignatius, references to “the Catholic Church” become more and more frequent. The ancient account of the martyrdom of Polycarp, who was bishop of Smyrna in the early second century, when Ignatius passed through on the way to martyrdom, routinely refers to “the whole Catholic Church throughout the world.” No better name has ever been found to designate the Church Jesus Christ founded than the name she acquired in her earliest years and which both Ignatius and Polycarp used as if it were the most obvious and natural term.

It goes without saying that Ignatius knew the Catholic Church was apostolic. In his letter to the Romans he spoke with the greatest respect of the apostles Peter and Paul who, he remarked, “gave orders” (4:3), and in the salutation to his letter to the Philadelphians, he spoke of the “appointing” of bishops, presbyters, and deacons-by which term he clearly meant the apostles’ handing on of the power of holy orders that they had directly from Christ.

There are even earlier witnesses to the Church’s apostolicity. About 80, the fourth pope, Clement of Rome (c.30-100) wrote to the Corinthians that the apostles of Jesus had “preached in country and city, and appointed their first converts, after testing them by the Spirit, to be bishops and deacons of future believers . . . They later added a codicil to the effect that, should these die, other approved men should succeed to their ministry” (42:4, 2). On the basis of such early testimony, there can be no doubt that the early Church understood herself as “apostolic,” as descending directly and organically, in an unbroken line, from the original apostles chosen and commissioned by Jesus Christ while on earth.

We have looked in some detail at evidence provided by one ancient Christian writer about what the Church was like and how she functioned around the turn of the first century. The witness of Ignatius is of utmost importance; his letters to some of the churches in Asia Minor testify to the existence, at this very early date, of a kind of Church that many have held to be the invention of later Christian generations that supposedly modified (and corrupted) the original plan Jesus Christ had committed to his apostles.

It is worth mentioning that both the authenticity and the early date of the letters of Ignatius are not in dispute today. Modern scholars accept these letters just as we have them. This is a remarkable scholarly consensus, considering the disputes that continue to rage about other early documents, even the Gospels.

The Church described in these letters dispensed both word and sacraments to the faithful. Its members believed and professed doctrines taught by its authority; they heard substantially the same Old and New Testament readings read today, and they participated in the Eucharist and other rites celebrated by men “set apart” and ordained within the same Church of Christ.

This common participation in the body of Christ oriented its members toward “doing good” (Acts 10:38). Ignatius wrote to the Ephesians that “by your good deeds [God] will recognize you are members of his Son” (4:2). In short, the Church at the end of the first century and the beginning of the second was not merely one, holy, catholic, and apostolic, but it was substantially the same in nature and function as today.

Other ancient testimony about the Church of the early Fathers confirms Ignatius’s evidence. We have already mentioned both Polycarp testifying to the catholicity of the Church and Clement testifying to its apostolicity. Similar evidence increases as we move further into the Christian era. By the time we reach the fourth century it becomes a flood. In the interests of brevity, we will confine our citations to the second century. If we confirm that the Church of the second century was the same as the one described by Ignatius, then later citations are almost superfluous. The Church of Ignatius was continuous with that of the apostles. If other early Fathers of second century are found to be in the same unbroken line, it is difficult to see where or how the plan of Jesus for a Church was altered, undermined, or “corrupted.” Rather, the supposedly corrupt institutional Catholic Church has clearly existed since apostolic times.

The burden of proof that the Church which actually emerged in the Roman Empire might not have been the Church Jesus intended rests upon those who assert that there was any significant deviation from the Church Jesus established. Some may prefer another model of the Church, but they are not doing justice to the historical evidence.

One of the most powerful and eloquent voices among the Church Fathers was that of Irenaeus of Lyons. In his prime he became a bishop in Gaul (modern France), but he too was actually a native of Smyrna in Asia Minor. Born around 130, Irenaeus recorded in his later years memories of the martyred bishop of Smyrna, Polycarp; he must have been about twenty-six when the latter was burned at the stake. Polycarp, of course, had preserved recollections not only of meeting with Ignatius, but of the preaching of John himself. Thus Irenaeus, although he was a second-century bishop, had a direct personal link with the generation of the apostles.

Irenaeus was a respected presbyter in the Church of Lyons at the time of the great persecution of Christians there in 177. In that same year he carried out a mission to Rome on behalf of Lyons and later succeeded the bishop-martyr there after his return. He seems to have completed his great work Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies) around 189, since the last one in his list of the bishops of Rome was Pope Eleutherius, who was succeeded by Pope Victor just after this.

It is possible to show that Irenaeus understood the Church to be holy, catholic, and apostolic from one single passage in Against Heresies. He wrote that “the Church, although scattered over the whole civilized world to the end of the earth [‘catholic’], received from the apostles and their disciples its faith [‘apostolic’].” It was through this same Church that God, “by his grace gave life incorrupt” to the faithful, whom Irenaeus called “the righteous and holy, and those who have kept his commandments and have remained in his love [‘holy’].” Irenaeus saw the Church as holy because she offered “a pure oblation to the Creator . .. The bread, which comes from the earth, receives the invocation of God, and then it is no longer common bread but the Eucharist . . . So our bodies, after partaking of the Eucharist, are no longer corruptible, having the hope of eternal resurrection” (IV:15).

Irenaeus was especially insistent that this holy Church was also one. He wrote: “Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things everywhere alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth. The languages of the world are different, but the meaning of the tradition is one and the same. Neither do the Churches that have been established in Germany believe otherwise, or hand down any other tradition, nor those among the Iberians, nor those among the Celts, nor in Egypt, nor those established in the middle parts of the world” (I:10:1-2).

It has been worthwhile quoting this passage at length because it illustrates how vividly Irenaeus, writing before the end of the second century, saw the Church as necessarily one. No denominational pluralism here! For Irenaeus, the Church was necessarily one, as she was catholic, because she was apostolic: She was based on “that tradition which has come down from the apostles and is guarded by the successions of elders” (III:2:2). “The tradition of the apostles,” Irenaeus added, “made clear in all the world, can be clearly seen in every Church by those who wish to behold the truth. We can enumerate those who were established by the apostles as bishops in the Churches and their successors down to our time” (III:2:3).

As we have noted, Irenaeus had a personal link with the generation of the apostles through his mentor Polycarp. If, toward the end of the second century, he believed that an unbroken succession of bishops was the guarantee of the authenticity of the Church, imagine what he might have thought about an unbroken succession of bishops that has lasted through the twenty centuries!

As a conclusion to this survey of the Church of the early Fathers, we can now rapidly cite, without going beyond the end of the second century, a few of the other early Fathers to demonstrate that Ignatius and Irenaeus are not atypical; they were in the mainstream of the early Church.

Clement of Alexandria was head of the famous catechetical school in Egypt. In bearing witness to the oneness of the Church, he alluded equally to her holiness, her catholicity, and her apostolicity. “There is,” he wrote, “one true Church, the really ancient Church into which are enrolled those who are righteous according to God’s ordinance . . . In essence, in idea, in origin, in preeminence we say that the ancient Catholic Church is the only Church. The Church brings together [the faithful] by the will of the one God through the one Lord, into the unity of the one faith” (Stromateis 7:16:107).

Another early Father, one of the first Christian apologists, was Justin Martyr (100-165). To him we owe some of the earliest descriptions of the liturgy. He is accordingly a most appropriate witness to the holiness of the Church. Like other early Fathers, Justin saw the sacraments of the Church as the means of its holiness, and he saw the transformed lives of its members as the result of this holiness. Just as Irenaeus stressed that the doctrine of the Church had been handed down from the apostles, so Justin emphasized that the power to administer the sacraments had similarly been handed down.

“A band of twelve men went forth from Jerusalem,” Justin wrote. “They were common men, not trained in speaking, but by the power of God they testified to every race of mankind that they were sent by Christ . . . and now we who once killed each other not only do not make war on each other, but, in order not to lie or deceive our inquisitors, we gladly die for the confession” (First Apology 39). Justin specified that a Christian who thus bore witness so selflessly had to be “one who believes that the things that we believe are true and has received the washing for the forgiveness of sins” (66). The baptized believer necessarily professed a specific doctrine and participated in the Church’s sacraments.

The principal sacrament of the Church, according to Justin, was the Eucharist. The Eucharist was not “common bread or common drink; but [just] as Jesus Christ our Savior being incarnate by God’s word took flesh and blood for our salvation, so we have also been taught that the food consecrated by the word of prayer that comes from him, from which our flesh and blood are nourished by transformation, is the flesh and blood of that incarnate Jesus. The apostles, in the memoirs composed by them . .. thus handed down what was commanded them: that Jesus, taking bread and having given thanks, said, ‘Do this for my memorial, this is my body’; and likewise taking the cup and giving thanks, he said, ‘This is my blood'”” (First Apology 66; cf. Mark 14:22-24, 1 Cor. 11:23-25).

Another second-century writer, Tertullian (160-230), wrote in a similar vein: “We marvel when a man is plunged and dipped in water to the accompaniment of a few words . . . It seems incredible that eternal life should be won in this manner . . . but we marvel because we believe” (Baptism2).

As for the catholicity of the Church, we have already seen how Clement of Alexandria called the Church “Catholic” almost as a function of her unity. We saw that by 156 the phrase “the whole Catholic Church throughout the world” was already current (Martyrdom of Polycarp, 8:1), while Polycarp himself was styled “the bishop of the Catholic Church in Smyrna” (16:2). This kind of testimony, reflecting a period relatively early in the second century, provides sufficient corroboration of the usage of Ignatius and Irenaeus, for whom “the Catholic Church” was simply “the Church.”

Finally, as for the apostolicity of the Church, we have seen how Justin Martyr bore witness to this while writing about her holiness. We can add to this testimony by citing Tertullian, who wrote how the apostles “first bore witness to the faith in Judaea and founded Churches there . . . In the same way, they established Churches in every city, from which the other Churches borrowed the shoot of faith and the seeds of doctrine and are every day borrowing them so as to become Churches” (De Praescriptione Haereticorum 20).

This is not a bad description of how the many local, individual Churches which belong to the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church of the later Nicene Creed actually were planted, took root, and grew. The process is still going on today. What early Fathers had already written by the end of the second century still applies, thanks to the constant missionary efforts that the Spirit continues to inspire. The Church of the early Fathers was nothing but the outgrowth of the Church founded by Jesus Christ upon the apostles, a Church which has neither ceased to exist nor been corrupted and which has lasted intact down to our own day.