This essay is the first half of a booklet published in 1921 by the Catholic Truth Society of London. In the preface then-Fr. Knox noted that “The following considerations formed the substance of a course of sermons delivered at Our Lady of Victories, Kensington, in October 1920, shortly after the pronouncements of an Anglican Canon on the Fall had aroused some interest in the newspapers. The text of the sermons has been slightly abbreviated, but no further effort has been made to edit them except insofar as the written word must necessarily differ from the spoken. The writer claims no specialist knowledge on any branch of natural science nor any originality for his views; he has simply attempted to turn the light of common sense on a subject which only calls for such treatment because so many of us are still content to be hypnotized by catchwords.” This reprinting preserves the whole of Msgr. Knox’s text; the only changes have been the regularization of spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

The theory of evolution has its own evolution through more than a century of scientific controversy; its own variations, now elicited by the need of adaptation to a changing environment in philosophical thought, in religious and even political history, now consisting of imperceptible modifications immanent in the process; and through it all runs, like a principle of natural selection, the iron law of inductive experiment, testing and winnowing the theories of yesterday and relegating what it has discarded to the fossil museum of the past.

The whole theory is only a theory still. But so far as concerns the general issue between the rival views of creative evolution and of special creation, of types fixed for all time and types merging into fresh types, it is enough to say that, whatever corroboration it may receive, the evolution theory neither detracts in any way from the sense of grandeur with which God’s creative work must affect all thoughtful minds nor promises to give any answer to the age-long “Why” that underlies all our modern cries of “How.”

But when we come to the position of man in this baffling system of creation, should we not expect that biological science, in proportion as its guesses arrive nearer at the truth of things, would illustrate in fresh lights the profound distinction there is between man and beast, the inherent fitness of man to lord it over the universe that has been made, it would seem, for his pleasure?

We all know that biological science does nothing of the sort. On the contrary, it has given us an undignified race of animals, not indeed as our ancestors—that is a misstatement—but as a sort of poor relations with a common ancestry in the background. And, while it admits that man is the nobler, because from the biological point of view the more complicated, type, and that the specific differences between the lowest type of humanity and the highest beast are significantly large, it is not prepared on that account to spare our feelings.

There may have been a series of animal types representing a slow gradation between ape and man, which have perished, according to the Darwinian law, only because their mixed characteristics did not qualify them to survive—types, you may suppose, that had just not enough tail to clamber up a tree when attacked, just not enough brain to dig themselves in behind it. Man’s title to live would thus, after all, be little better than an accident. Or, on the Lamarckian view, this noble and complex structure, the human body, may have only been called into existence through generations of struggle, by an automatic response to the exigencies of our environment.

Whatever more modern reconciliation or rehandling of these views be the dominant hypothesis, it is at least clear that on the evolution theory man’s physical structure is not the sudden miracle of intrusion upon nature that our ancestors have deemed it; the human race has made good only on the same terms as the other dominating species, and by weapons analogous to theirs; and, if man has become lord of creation, it would seem that he has won his position as the optimists say Britain won her Empire—only in a fit of absent-mindedness. We cannot even say that it was the human intellect, as such, which secured the triumph. Rather, it may have been an instinctive movement which called forth the first complications of our psychology, even the first elements of our civilization—a movement as instinctive as that which turned the beaver into an architect and the hunted stag into a strategist.

If it can be proved, so far as such matters are capable of proof, that man’s early development is thus parallel with that of the brute beasts, is there anything left to us in virtue of which we can call man the master—not merely the highest product, not merely de facto the tyrant, but by God-given right the true lord and master of creation? There is.

Run “instinct” for all it is worth; show how man’s delicate sensibility in a thousand directions is but the hypertrophy of such instinct; collect whatever instances you will of inherited tendencies, of herd-psychology, and the rest of it—you still come up against a specific difference between man and brute which eludes all materialist explanation: I mean the reflective reason.

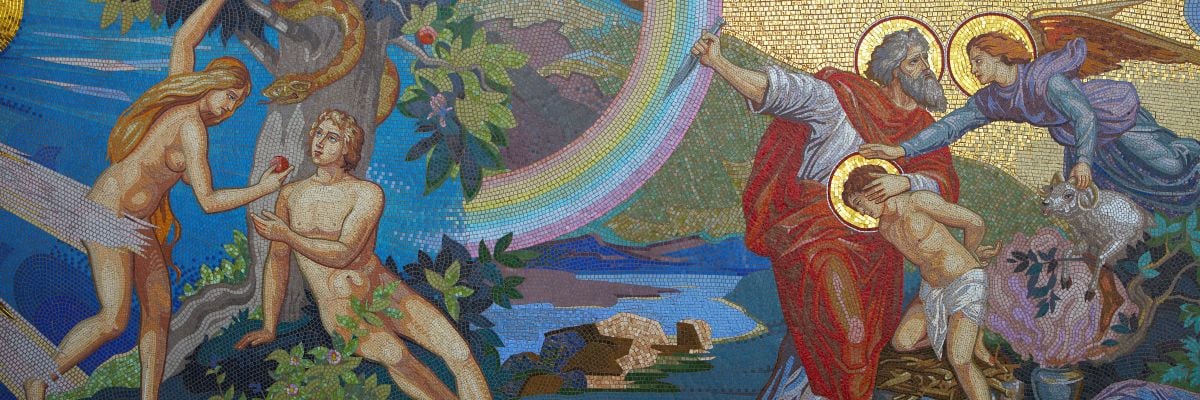

When your attention, instead of being directed toward some object outside yourself is directed toward yourself as thinking or toward your own thinking process, that is the work of the intellect, that is man’s special prerogative. When Adam awoke in the garden, we dare not guess what monstrous forms of animal life, what wealth of vegetation our world has forgotten, his eye may have lighted upon. But we do know what was his strangest adventure, because it was an adventure he shared with none of his fellow-tenants in Paradise. His strangest adventure was when he met himself.

Here at least, wherever else you trace continuity, discontinuity begins. The difference between dead matter and living, the difference between unconscious life and life that is sensitive, are not more absolute than the difference between the living thing that can feel and the living thing that can reflect upon its feelings The phenomenon of the intellect, considered in itself, is not subject to any material laws or susceptible of any material explanation. As a mere matter of psychological analysis this phenomenon, whatever we make of it, is an intrusion upon the brute creation, a sudden epiphany of the immaterial world within the material horizon.

Man is the object of his own thought, and in the direction of that act he borrows nothing whatever from his material surroundings. There you have the casket in which the secret of man’s identity is locked up, beyond the reach of all biological speculation.

And it is because the impressions man receives through his senses are not simply isolated impressions that die and pass, are not simply stored up by a pigeonhole system of unconscious association, but related and digested in his thought by the work of the independent, organizing intellect, that man is master of creation still.

He alone is the spectator of all time; him alone the music of the spheres has for audience. The buffets of experience from without are no longer mere chisel-blows that blindly fashion the evolution of the type; they are transmuted into terms of spiritual experience and become part of the individual history, with its loves and hates, its hopes and despairs, its outlook upon eternity.

The same intellectual quality, which is philosophical proof that man’s spirit is immaterial, is at the same time the index of man’s place in the scale of being. He alone, of things visible, is related to the universe as self-conscious subject to object; but for him, the panorama of creation would, for its own tenants, be like a cinema played at St. Dunstan’s Home for the Blind.

Is man a development of the beast? Why, certainly. Did you not know that you were a brute once? That when your bodily frame first came into existence, you had no right to be thought higher in the scale of creation, more precious in the sight of God, than the unborn young of an animal? We did not need Weismann to tell us that one acquired characteristic cannot be inherited, the characteristic of being a rational creature.

We knew that God first formed man of the slime of the earth–of one kindred with the beasts that perish, and only afterwards, only when God breathed into his face the breath of life, did he become a living soul. And if it should prove that our bodies, this slime we were formed from, is part of a coherent system of gradual biological evolution, we are still, as intellectual creatures, the enfant terrible of natural history, a cuckoo’s egg in the nest of bewildered creation.

Man is the pivotal creature; the spiritual and the material have their liaison in him. No discovery of science can abase man’s dignity, so long as his mind rests in that truth and his will in that high ambition.

The Will

It must be obvious to anybody that a man’s actions are in great part determined for him by conditions for which he is not then and there to blame; sometimes, for which he is not to blame at all. Suppose a man is born of an unhealthy stock, so that he has a morbid strain in his very blood; suppose him brought up in a home and among companions whose influence over him is all evil; suppose that by a long course of vicious living he has fallen into fixed habits of self-indulgence.

When that man tosses off, with already trembling fingers, the last glass of drink that nerves him to go out and commit a murder, can we really call his action free? Does it really differ in kind from the instinctive fury with which the madman turns against his captors or the lion falls upon its prey?

The answer to that is a blinding, overpowering conviction of the human conscience. We believe the actions of the lower animals to be determined for them, wholly and completely, by instinct and by training and by circumstance, even when they seem most faithfully to parody the deliberate decisions of man. Sir William Watson, for example, describes a collie dog out for a walk with his master:

“Shall we take this path or that? It matters not a straw. But just a moment unresolved we stand, and all his personality, from ears to tip of tail, is interrogative. And when, from pure indifference, we decide, how he vociferates! How he bounds ahead! With what enthusiasm he ratifies, applauds, acclaims our choice ‘twixt right and left, as though some hoary problem, over which the world had puckered immemorial brows, were solved at last and all life launched anew! ”

We know, most of us, those mannerisms of the brute, and yet we can see through them and laugh at them. But when we consider the actions of man, we think, we talk, we behave—even in the most solemn circumstances, when life and death depend upon our behavior—as if man had a will and must be held responsible for what he does.

I do not say that whenever a man acts freely he is conscious at the moment of free action. On the contrary, it generally feels at the moment as if the motive which induces us to act as we do, rightly or wrongly, were a tyrannous influence from which we cannot escape. But when the action is complete, whether it is our own or that of another, we do get the sense that, if the agent had wished, he could have acted differently—”I oughtn’t to have said that,” “He had no right to behave as he did.” That means that the action was not determined but free, and we testify to our belief in the responsibility of the human agent whenever we think of reward or of punishment.

It is fatal to be misled into explaining away the concepts you find in your experience. “After all,” people say, “what do we mean by a reward? Isn’t it simply a bribe to make people do the same again, just what we do when we give a dog a biscuit to make it do a trick? And a punishment,” they say. “Isn’t it simply a threat to prevent people doing the same thing again, just what we do when we hang up dead moles on a barn door, to teach the other moles not to come rooting about our property?” That isn’t true. We bribe animals, we threaten animals, but it is only men that we punish and only men that we reward.

I am a schoolmaster. Supposing there are three boys in my form who don’t know their lesson. One of them says he really worked his hardest, but couldn’t make head nor tail of it, and I’m inclined to believe him. The second forgot, simply forgot, that any lesson had been set. The third, it is clear, has simply been slacking. Well, it may be that in the interests of discipline I make them all write out the English of the lesson three times.

But in the case of the first I am simply doing it for his education, so as to impress on his memory what he has failed to impress on it for himself; in the case of the second, I am simply correcting him; I don’t blame him for his forgetfulness, but I’m going to give him a lesson which will make him less forgetful in future. It is with the third and only with the third—the boy who could have done better than he did—that my action can be properly described as punishment.

But of course your modern psychologist will think that all this is a very superficial analysis. “Are you quite sure,” he says, “that you’ve diagnosed your feelings rightly? In the last few years we’ve come to know much more about the curious little kinks and twists which are to be found in the make-up even of a sane, ordinary mind. Sometimes we can explain these things—a shock, for example, experienced in boyhood, may make a man nervous about fire or afraid of the dark or something of that kind; the impression left by the experience has lingered on in his subconsciousness long after, it may be, the actual memory of the incident has passed from him.

“Since our minds are so curiously constructed, may it not be that the conscience you tell us of is, after all, one of these illusions? That the scoldings and the whackings and the standings in the corner which have been inflicted on us when we were young have produced in us the illusion that we are responsible for our faults, when really our actions were all determined by heredity, by environment, by instinctive movements? After all, you priests (they tell us) come across plenty of scrupulous people who think some action of theirs was voluntary when in reality it’s quite plain that it wasn’t. If we can make such mistakes once, why not always? If we are sometimes wrong in thinking that we acted freely, isn’t it possible that we are always wrong?”

The answer to that is, No. The human mind cannot simply invent, cannot think without having the material for its thought supplied to it by experience. And if the doctrine of determinism is true, and there has been no such thing in all human history as a free act, then the very idea of free action is one the human mind could not have conceived for itself. I quite admit that, knowing in your experience what it is to sin, you may sometimes through scrupulousness give a wrong label to this or that action and suppose it to be a sin when it was really only a mistake. But you couldn’t even wrongly suppose it to be a sin if there weren’t such an experience as sin or if that experience had not been felt by the human race.

I can mistake Mrs. Brown, whom I know, for Mrs. Smith, whom I know, but I can’t mistake her for Mrs. Jones, whom I don’t know—even a wrong judgment must somewhere have a basis in reality. If you break your hostess’s best sugar-basin by some quite unavoidable accident, you have a feeling at the time that is very much like the remorse you feel after committing a guilty action. That’s a mistake. But you couldn’t mistake your feeling for remorse unless you had learned, somehow, to attach a meaning to the word “remorse.”

I don’t mean to say that, when you have thus vindicated the freedom of the will, the problem of free will is an easy one, even in psychology. We say, “What motive induced you to be so cruel?”—do we then imply that our motives, our estimates as to the good and the harm, apparent or real, that will result from our action, are tyrants that force us into doing what we do? Why then, we are determinists once more: Motives have swayed our action from first to last, and there is no room left to put anything of ourselves into it. Or do we mean that, having weighed up the motives for and against the suggested action, we then proceed to choose our course quite independently of them—that our actual choice is determined by nothing whatsoever?

Why then, the freedom of our actions is meaningless; it is at the last moment a mere whim, a mere caprice, that is the explanation of our action. Neither of those two positions will do. Just as there is no explaining of the way in which subject and object interact upon one another in our knowledge, so there is no explaining of the way in which our will and the motives which inspire it interact upon one another when we choose between two courses of action. It is a mystery, and we must bow to it.

But this we can say, that any philosophical theory which tries to persuade us that what heredity, and environment, and education, and habit have made of us, that we are and always will be; that there is no room left for the free action of the human soul, no chance of retrieving the past and making good once more; that, consequently, men cannot, just as animals cannot, be in the true sense rewarded or punished for their actions, but only bribed into repeating their good actions, or deterred from repeating their bad actions–such a philosophical theory, I say, is false to the whole of our moral experience and inconsistent with the first principles of Christianity. It may be easy enough to accommodate it to the dark, fatalistic religions of the East or to Western imitations of them, but the religion which Jesus Christ founded appeals to man as a free agent, responsible for the use he makes of his opportunities and for the choice of his eternal destiny. Even the lost souls in hell have this dignity, that they are where they are of their own choice.

The Fall

The book of Genesis gives us a picture of man at his first beginnings as a prince exiled from his heritage. Science, dealing with the same period, gives us a picture of man as a baby, first groping his way, then beginning to find himself, then growing and developing by gradual upward stages into the self-appointed dictator of a world that has bowed to his cunning. Let us understand that the issue here is not concerned with a mere question of historical fact. We do not expect science to deal with questions of historical fact.

When the biologists started out to give us an account of our origins, we did not expect them to discover for us the remains of rudimentary legs in the serpent. When we sent the archaeologists exploring, we did not expect them to return in triumph with a fossil apple, bearing unmistakable marks of a bite on each side. If there were any contemporary records by which to assess the value of the story of Genesis, it would be to the historian, not to the sciences, that we should look for guidance. Nor are we likely to quarrel with the man of science if he discovers, or if he conjectures, that the earliest human creatures of whom he is able to find any traces were degraded bushmen instead of half-heroic beings. It was Rousseau who believed in the “noble savage,” the unspoilt child of nature from whom our civilization has degenerated. Christianity did not expect man, after the Fall, to be such a character as that. Whatever gifts Adam possessed in the time of his innocence that were superior to yours and mine were forfeited, absolutely and finally, by the Fall, and it is no news to us that our civilization, where it is true to itself, has left Cain and Lamech behind.

In fact, our position is not that of people who suppose that the story of our race involves an early degeneration from a high to a low standard of morals or of culture. The failure of Christian doctrine to fall into line with the theories of the evolutionist lies deeper than that. This is where the quarrel lies. If the story of the Fall is true, then the human conscience—and since we are all sinners, the human consciousness of sin–must be present in man from his very first beginnings.

However much our moral standards may have changed in their particular application—as, for instance, in the setting of a higher value on human life—man has always had the power to realize that he is sinning when he sins and the knowledge that such conduct is contrary to the law of his Creator and the terms of his creation. But if human history is to be brought into line with the whole history of animal life on our planet, then we should expect that the knowledge of God and the consciousness of sin developed gradually in man’s soul, just as certain capacities–the capacity, for instance, to stand upright on two legs—would be supposed to have developed gradually in his body. And, further, those keener moral perceptions ought somehow to have been developed by him in the course of his struggle for existence, in answer to the needs of his surroundings, or as the title by which the race continues to persist in a world the weakest goes to the wall.

Now, supposing that divine revelation had told us nothing at all about the dawn of human experience and that we were left entirely to the guesses of the biologist for information about our earliest past, what sort of theory should we construct for ourselves? Something, I suppose, like this—that man when he first won his right to survive knew no restriction upon his actions except such as mere instinct provided; he had no theory of controlling his desires, no sense of cruelty or of injustice; that he lived as beasts live, the blameless child of unrestrained instinct. Gradually he found that his opportunities for gratifying his desires had outrun the limit within which he might safely indulge them. Disease followed or, if not disease, at least an enervated constitution, or mere worldly caution taught him the first elements of orderly conduct:

“Philosophers deduce you chastity or shame, from just the fact that at the first whoso embraced a woman in the field threw club down, and forewent his brains besides, so, stood a ready victim in the reach of any brother savage, club in hand; hence, saw the use of going out of sight in wood or cave to prosecute his loves.”—so Bishop Blougram read in his French book.

Further, when instinct or common sense warned our forefathers that it was more conducive to the general happiness if they lived in tribes and in village settlements than if they lived isolated on the one-man-one-cave principle, it began to be seen that life in a community involved some give-and-take in matters of gentleness and of honesty. A rude compact that if you stopped stealing your neighbor’s eggs he would stop clubbing you over the head would have in it the germs of what we call law and order. And gradually, as these advantages came to be more clearly seen, and even drawn up in some code of law, gradually, as the younger generation became accustomed to the idea of self-control and of observing your neighbor’s rights–when all is said and done, you can do a great deal by beating a boy—there would grow up in some dim region of the human consciousness the sense that what medicine discouraged and what law forbade was not only insanitary, not only illegal, but positively wrong.

That is a very pretty picture; the chief disadvantages attaching to it are that it isn’t true; it doesn’t explain what it set out to explain, and it is quite out of harmony with the whole of Christian morals.

It isn’t true—that is to say, there is not a shred of evidence for it–and our friends the anthropologists, who make it their business to throw what light they can upon the principles of primitive human society, have lately given up this attempt to explain away morals as taking their origin from mere worldly convenience. They will tell you on the contrary that some sort of religion or “magic” comes earlier in human society than the making of laws for purposes of practical convenience. The social contract is out of date.

And it doesn’t explain what it set out to explain. The sense of distinction between good and evil, between right and wrong, is something totally different from the sense that such and such a thing is harmful or that such and such a thing is contrary to the welfare of the community. Once again, I quite agree that if you have got the idea of right and wrong in your head, it is possible to have a false conscience, to mistake what is really indifferent for something wrong, and vice versa. But if you don’t start with some general idea of right and wrong in your head it is impossible to see how it is ever going to get there. There may be precious little difference between the degraded savage who’s got very little conscience and the beast that has got none at all. But the difference, such as it is, is definite and absolute.

And it’s quite out of harmony with the whole of Christian morals, for it means that virtue—the observance of the distinction between right and wrong—is simply one of the weapons which have enabled the human race to survive. Justice is simply a means to prevent the human race exterminating itself by quarrels, continence simply an expedient to save it from physical degeneration. If that were all virtue is, then we should have to say that the death of our Lord on Calvary had taken that code of morals and written across it in letters of blood, “Cancelled.” The law of biology is that he who loves his life shall save it; the law of Christ is that he who loves his life shall lose it.

It is the deliberate doctrine of our Lord and Master that there is no survival of the fittest in the heavenly economy, that the unfittest to survive in this world is the fittest to survive through all eternity with God. There is no room for arguing over it; if natural morality is simply a sort of protective shell which the human race has formed around itself for its own preservation, then Christian morality, the morality of the Sermon on the Mount, is a diseased and pernicious growth, and ought to be cut away.

But after all, why should we expect the history of human morals to follow the lines laid down for it by the fancy of a few dogmatic evolutionists? We have seen that the human intellect is not and cannot be an incident in the course of natural evolution, but is a sudden intrusion upon the natural order of things.

We have seen that mankind has again wandered aside from its proper evolutionary orbit by being found in possession of a will that is free to choose and responsible for its choice. If this be so, surely it is clear that the history of the human conscience will be altogether outside the course of ordinary biological happenings, that the human conscience, too, is not a gradual growth in us, but a sudden intrusion, part of a different order of creation.

True, we couldn’t know that man was created innocent and has fallen from his innocence. Philosophy wouldn’t determine the point for us, though our whole experience of the moral struggle in ourselves, the conflict between the law of sin in our members and the law of grace, is such as befits the condition of beings that have fallen from what they once were.

But philosophy does say to biological science, “Stand aside here.” And while it stands aside, divine revelation steps in and shows us what we once were–were for an infinitesimal moment of history and shall never be again. God made man right, and he hath entangled himself in an infinity of questions. What wonder that man is a come-by-chance in the system of creation, if the very earliest incident in his career is indeed the story of an arrested tendency, a divine purpose thwarted?

Read Part II here.