The first-century Didache sees in the Sunday Eucharist a clear fulfillment of Malachi 1:11: “For this is that which was spoken by the Lord: ‘In every place and time offer to me a pure sacrifice; for I am a great King, says the Lord, and my name is wonderful among the nations.’”

The sacrifice is prefigured by the ancient Passover sacrifice, which consisted of two parts: the killing of the Paschal lamb on Preparation Day, Nisan 14 (Exod. 12:5-6, Lev. 23:5), followed by the Passover Meal on Nisan 15 (Exod. 12:8, Lev. 23:6). In the Passover meal, each household (or cluster of households, if a family was too small) was instructed to “eat the flesh that night, roasted” and to “let none of it remain until the morning” (Exod. 12:8, 10). In eating the flesh of the lamb, the people participated in the sacrifice, thereby completing it.

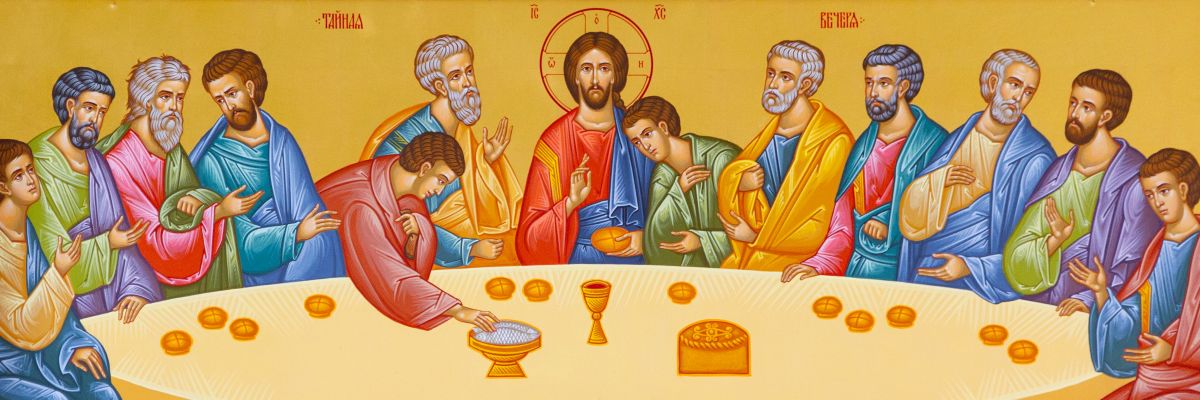

This prefigures Calvary and Holy Thursday and the sacrifice of the Mass. St. John refers to Good Friday as “the day of Preparation of the Passover” (John 19:14), while Jesus called his Last Supper the “Passover” (Matt. 26:18, Mark 14:16, Luke 22:8), with Jesus himself as our “Paschal Lamb” (1 Cor. 5:7). While Jesus’ sacrifice on Calvary was done “once for all,” he instructed the apostles to continue the sacrifice of the Mass, saying, “Do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19).

St. Paul explains that, in this way, we participate in Christ’s sacrifice: “are not those who eat the sacrifices partners in the altar?” (1 Cor. 10:18). Paul’s argument, contrasting the “table of the Lord” with the Jewish temple sacrifices and the “table of demons” (i.e., demonic altars), makes sense only if there is a “true and real sacrifice of the Mass” (Council of Trent).