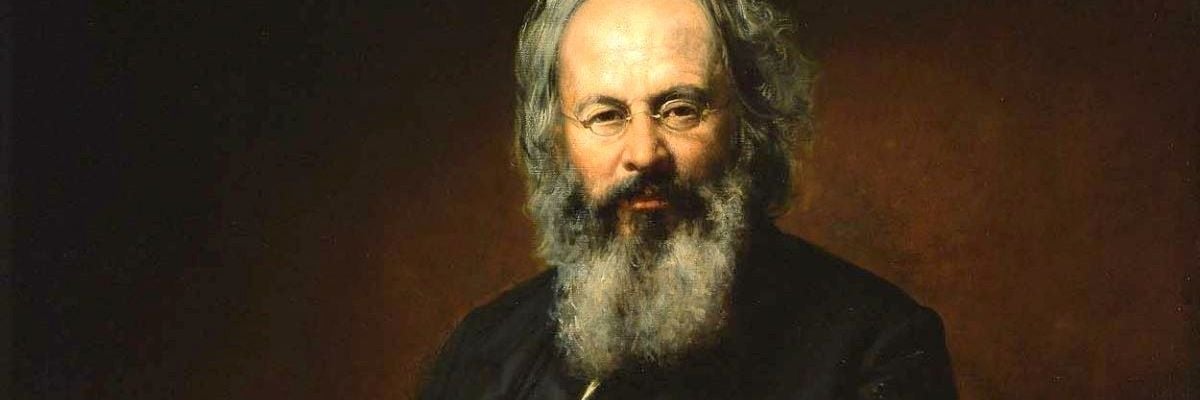

Orestes Augustus Brownson (1803–1876) in his day was a well-known publicist and essayist. After his conversion in 1844 he became, primarily through the pages of his Brownson’s Quarterly Review, the leading lay apologist for the Catholic Church in the United States. Outside of academic circles he is less well known today. In fact, by 1937, when playful youths toppled his bronze statue in New York City’s Riverside Park, The New York Times reported local historians and residents were stumped as to the identity of the man so memorialized in 1910. A reacquaintance with the career and controversies that engulfed Orestes Brownson will provide beneficial insight into the difficulties of being an effective apologist during a contentious era in American history.

He was born in Stockbridge, Vermont, and in his early years was a friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau along with other leading New England intellectuals and transcendentalists. His circuitous path to Rome led through Congregationalism, Presbyterianism, Universalism, socialism, atheism, and Unitarianism. Finally, after being convinced of the Church’s historic position and claims, he rejected private individual judgment and accepted Catholic orthodoxy and authority.

Brownson believed Protestantism passed through three stages. The first was when the power of the state promoted and controlled the emerging religions. Secondly, after the rejection of temporal authority faithful congregations formulated their own beliefs and practices. Unrestrained individualism lastly takes hold and Protestantism descends into a morass of conflicting sects where popular will, interest, and vanity—rather than divine will—prevails. After this intellectual and personal journey, Brownson discovered Rome.

Brownson’s Quarterly Review was founded in 1844. It consisted mainly of essays and book reviews. After his conversion his articles took on a Catholic perspective, and subscriptions dropped. He wanted to retire from journalism and enter law; however, Bishop Fitzpatrick of Boston persuaded him to continue the Review because the Church needed a bold champion in the United States. The Plenary Council of Baltimore (1849), at the urging of then Bishop Kenrick, issued a letter of endorsement that appeared on the back covers of the Review. Subscriptions picked up and the Review was saved.

Orestes Brownson was a robust and dynamic defender of the faith. In public restaurants in the years shortly after his conversion he would make loud Friday demands for fish and would relish the polemics against those who berated him for his religious views. This aggressive apologetic style was provocative to Protestants and even to his co-religionists. He was not a leader of Catholic thought in the sense that through cogent reasoning others were convinced. Frequently the response was negative, eliciting critical explanations, mollifications, or refutations.

In the 1850s the U.S. Catholic Church was going through a transition. Its ranks were swelled by European immigration, especially the famine-plagued Irish. Many native-born U.S. citizens erroneously connected Catholicism with something alien and dangerous to the American way of life. It was this association that Brownson sought to smash by a forceful assertion of both his Yankeeism and his Catholicism. His essay on native Americanism—that is, those born in America—defended national customs and habits while setting forth his plan to destroy the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing movement.

Brownson believed that ethnic groups must conform to American standards. He maintained that foreigners invite attack by being insensitive to American values, by belittling the predominant Anglo-Saxon race, and by following political demagogues. On the other hand, he denounced the Know-Nothings, not for their nativism but for their desire to restrict religious liberty. In this they were un-American. Native citizens were advised to be tolerant of foreigners because someday from out of their “narrow lanes, blind courts, dirty streets, damp cellars, and suffocating garrots, will come forth some of the noblest sons of our country, whom she will delight to own and honor” (Brownson’s Quarterly Review, third series, 2 [July, 1854], 328–354).

The Irish community was outraged at what it perceived as some disparaging remarks directed against them. Many Catholic newspapers denounced him for insulting immigrants and stirring anti-Irish sentiment. Catching fire from both sides, Brownson felt that he had to fight against Americans to defend his right to be Catholic and against Catholics to defend his right to be American.

As part of the defensive psychology of the American Catholic population in the 1850s, bishops were urging the establishment of parochial schools. To this policy Brownson did not give full concurrence. Although he wanted children to have religious and moral education—provided it was well taught—and though he favored the founding of parochial schools as a safeguard to faith, he stood opposed to them if they were to be primarily a means of preserving foreign cultures in this country. He believed that the development of the common public schools was vital to the growth and well-being of America, that Americans were justly proud of them, and that they were not as corrupting as some immigrant Catholics claimed.

Rather than pressure the state into subsidizing the creation of a separate school system, Brownson worked to force all textbooks and practices hostile to Catholics out of the public schools. Moreover, he believed that no school, public or private, could guarantee good and virtuous persons. This responsibility rests primarily with parents and the home environment. Parents were fooling themselves if they believed that establishing separate schools would ensure better Catholic children who would be more faithful adults.

Since Brownson always placed the Church above all things, his stand on immigrants and parochial education was not motivated primarily by nationalism. But his conception of the mission of the Church in the United States was at odds with the prevailing attitude. He advocated waging a vigorous, aggressive campaign against Protestantism because only by strenuous proselytizing could America be converted to Catholicism. He felt that the Church would never make progress in this country until it became more distinctly American and less of a Celtic institution.

This attitude did not sit well with a hierarchy and clergy drawn largely from those of Irish background. American prelates did not share Brownson’s optimism concerning the conversion of the United States. They were occupied with preserving and strengthening what they already had. This of course necessitated a defensive and protective policy. No doubt this basic difference of opinion over the role of the Church in the United States lay at the root of most of the disputes which he had with the hierarchy and other co-religionists.

But Brownson was far from advocating a national or schismatic church. All he contended was that within Catholicism certain national distinctions do occur; and, within limits, preference for one’s own country is permissible and should be respected. When American and Irish interests clashed, he favored Americanism. But in a dispute with Catholicism, no nationality could be in the right. This Americanism was nothing like that condemned by Pope Leo XIII in 1889 with his Testem Benevolentiae.

In fact, Brownson had great respect for the authority of the pope. He believed that when one felt aggrieved by local ecclesiastical authority, one’s recourse was not to disobedience, resistance, or public discussion but in appeal to Rome, the highest tribunal and ultimate arbitrator. In 1861 the Propaganda in Rome reviewed his writings on the temporal powers of the pope and some minor speculations on eternal punishment. Willingly he submitted himself to the judgment of Rome. “If my Review ‘has gone astray,’ I am anxious that it should at the earliest moment return to the true path, and I can assure his eminence that I have no pride of opinion to gratify, and that the Holy See will always find in me a docile and obedient subject” (Henry F. Brownson, Orestes A. Brownson’s Later Life, Detroit [1900], 254).

The Propaganda was satisfied with his explanations and disposition so the charges went unsubstantiated. Indeed, it was this intense loyalty to the Vatican and its supremacy that led Brownson to proclaim the doctrine that most disaffected himself from American Catholics: ultramontanism.

Brownson believed that to separate the spiritual from the temporal was political atheism. Sovereignty cannot be based on the absolute will of the people because all authority comes from God. Therefore, divine law limits the state as well as the Church. Both the Church and the state are separate orders operating within independent spheres.

The state has no superior in its own order, but its own order is inferior and subordinate to the spiritual order—that is, to the Church, the kingdom of God on earth. The state is subject to the law of God; and so long as it obeys that law as declared and applied by the infallible chief of the spiritual power, the Church does not interfere with it or censure its enactments or administration. The pope speaks only when the law is violated and the rights of God are usurped, and he speaks then not by reason of the temporality but by reason of the spirituality, and judges “not the fief, but the sin” (The Works of Orestes A. Brownson, ed. Henry F. Brownson, New York [1966], XIII, 436–437).

To the extent that the Church is autonomous in the United States, Brownson was convinced that the U.S. Constitution implicitly recognized this principle. When there was a conflict between the Church and the state as to what is the will of God, the only infallible interpreter of that will is the Church as embodied in the office of the pope. However, the papacy’s powers over the state were indirect; it could exercise only spiritual and moral force. Brownson concluded that Catholicism is vital for the preservation of the republican form of government and that if Catholicism is not to perish in the United States, this country must be converted.

The greatest theological controversy that embroiled Brownson was with a fellow convert from across the Atlantic, John Henry Newman. The paths these two men followed to Rome were quite different. Brownson sought a source of ultimate authority to give meaning and coherence to existence. Newman had to reconcile the apparent divergence between the patristic writings and the present Catholic dogmas. He accounted for this discrepancy in his Essay on the Development of Christian Dogma, shortly after which he was received into the Catholic Church.

This essay theorizes that while the deposit of faith was held implicitly in the early Church, it became explicit only throughout the course of time. Brownson, then a recent convert himself (hardly versed in patrology), thought that Newman’s theory was heretical and opposed to the timeless immutability of the faith; and so he attacked this idea of developmentism.

Newman rather resented this criticism but would not respond to it. In 1852, in the Dublin Tablet Newman mentioned a personal attack and by a layman, but he still refused to counter Brownson’s charges. Despite this theological dispute both men respected one another. When Newman was appointed rector of the prospective Catholic University of Ireland, Brownson was offered a teaching position. A young and enthusiastic John (later Lord) Acton wrote Brownson encouraging him to accept. However, Brownson withdrew his acceptance upon discovering that Newman being pressured from Irish bishops opposed to hiring him. Repercussive waves from his essay on nativism had reached their shores.

Brownson’s devotion to Church and to country did not dichotomize his values. To him their interests were inseparable. When he spoke out on nativism, education, ultramontanism, et cetera, he was saying that the Church in America should be American and America should be Catholic.

Brownson took a lead in theological discussions, which was seldom done by Catholic laymen. His independent spirit was drawn into conflicts with others who tried to use Church authority against him, but he did not transgress the legitimate bounds of authority. Having respect for both liberty and authority, he was wise enough to distinguish the areas in which he was free to differ with his fellow churchmen and the areas in which no Catholic could differ and still remain a true Catholic. At times personal liberty might compel one to strike hard at popular Catholic thought and action for the betterment of the Church. But the Church is ultimately the judge of its own best interests to which all of its believers must conform when formally pronounced.

Although his public life reflected this conflict of liberty and authority, he seemed to be unaware of this paradox in his personal opinions. He once explained to Protestant critics that he did not enter the Church to reject Protestant liberty in order to accept Catholic authority. “We went to the Church from a theory which was invented to retain them both and to reconcile them systematically and really one with the other” (Later Life, 254). Brownson believed that only the Catholic Church provided the milieu for the true harmonizing of liberty and authority. Liberty could exist only under authority, and authority guaranteed true liberty.

Ten years after his death, his body was re-interred in the Brownson Memorial Chapel of Sacred Heart Church on the campus of the University of Notre Dame where his papers are archived. His epitaph, inscribed in Latin, summarizes his life and achievements:

“Here lies Orestes A. Brownson, who acknowledged humbly the true faith, lived a complete life, and by writing and speaking courageously defended his church and country, and, granted that his body may have been taken by death, the endeavors of his mind remain immortal monuments of genius.”