We all know what Jesus looks like, right? We’ve seen his face countless times. It has been portrayed by countless artists, using every artistic technique and medium. His is probably the most depicted and most easily recognizable face in history. But do any of these portraits actually look like him? Nobody alive today has ever seen Jesus in the flesh, and no artist we know of was blessed to have had him sit as a model, so is there any sense in which these depictions can be called portraits? Do they show us the “real” face of Jesus, or are they creations of the artists’ imagination? In short, does any trustworthy description or definitive portrayal of Jesus exist?

Not Even a Verbal Portrait

The Bible is no help. The New Testament writers seem perfectly oblivious to our curiosity about Jesus’ physical appearance, and one searches their words in vain for even the slightest reference to it—or anyone else’s, for that matter. The inspired writers knew that their appointed business was to give us an account of who Jesus was and what he did, not to draw a verbal portrait of him. Similarly, while the Church fathers occasionally debated whether Jesus was beautiful or ugly—”someone from whom men hide their faces”—they offer no specific details.

There are, however, dozens of apocryphal descriptions of Jesus to be found in Gnostic and other non-canonical texts—notably, in spurious letters from Pontius Pilate’s predecessor, a certain “Publius Lentullus,” and another, supposedly from Pilate himself. These indeed may have provided the basis for early portrayals of Jesus, or they themselves may have derived from paintings the writers had seen, but either way, their accuracy cannot be relied upon.

What about Inspired Images?

What of putatively miraculous images like the Shroud of Turin, or those made in response to private revelations like St. Faustina’s image of Divine Mercy? While these depictions of Jesus enjoy an undeniable authority and prestige, and may be approached with the eyes of faith, it doesn’t seem possible to confirm their verisimilitude.

On the other hand, it could be expected that the inspired tradition of icons would provide the most accurate likeness possible: What could be better than a divinely revealed portrait of Jesus? But icons, like the Scriptures, are not interested in recording the superficial details of someone’s physical appearance. They downplay and abstract the shifting visible features of the person in order to reveal the eternal, invisible essence—the soul. That is the “real” person, the real portrait.

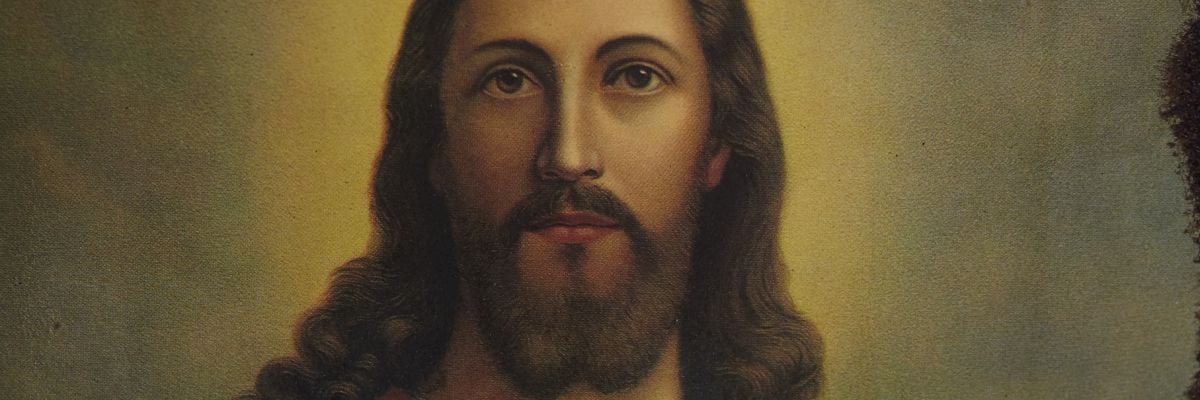

Nevertheless, icons display a familiar, if not completely realistic-looking Jesus: oval-faced, bearded (though not heavily so), with long dark hair parted in the middle, a small mouth, large forehead, and large, “soulful” eyes. It is a face in fact strikingly similar to the one on the Shroud of Turin. Over the centuries, it is this bearded Jesus that has become the de facto model for artists in both the iconographic and non-iconographic traditions.

There are competing non-iconographic forms, however, that depart from this standard. One of the earliest is a youthful and beardless Jesus, depicted in the second-century catacombs under Rome. He is usually dressed in a toga, and looks distinctly Roman or Hellenistic, presumably something like the artists themselves. Later variants include the heroically muscular Renaissance Jesus and the “historically accurate” Semitic Jesus.

In no case, however, can there be any question of an authentic likeness. These are all “made up” portraits. Jesus is shown abstractly in icons, according to tradition, and with conventional or idealized features in non-iconographic images. Each artist gives him a different face (sometimes based on the artist’s own), and the variety seems limitless: He has been portrayed in the guise of blonde Caucasians, Africans, Asians, and every other ethnicity. Remarkably, this doesn’t seem strange—imagine if, say, Pope John Paul II were depicted with the same freedom—although there is a danger of transforming the particular man Jesus into a sort of generic “human.” It’s even conceivable that among these manifold portraits one or two actually have a chance resemblance to the real Jesus.

Appearance—or Essence?

But does it matter? Augustine regards it as completely irrelevant to our salvation what we imagine Jesus to look like. Although he was manifested in the flesh, with a specific form and features that could have been photographed, Jesus was “all things to all people.” Artists depict a Jesus that “looks like us” in order to convey a lively and immediate impression of who he was, or they use iconographic abstraction to represent his essential nature. It is perhaps only in the Modern era, when a skeptical and critical distance from the spiritual is expected, that a preoccupation with finding the physical face of Jesus has developed.

We say that a good portrait captures the “real person,” the essence of who he is. No form of art can show us with certainty what Jesus really looked like, but art can show us who Jesus really is.