Do any of the following statements sound familiar?

“It’s my way or the highway!”

“You can’t tell him anything.”

“I don’t care what anyone else says . . .”

Or even: “Honey, please stop and ask for directions.”

These and many similar comments point to how our stubborn pride keeps us from seeking the input of others—usually to our own detriment. We often lack the humility to realize that we don’t have all the answers, that we can and must learn from others.

There is a virtue that helps us to overcome this false sense of self-sufficiency. That virtue is docility, which is simply the ability to be taught. As a Christian virtue, docility is what enables us to be formed in the Catholic faith, to grow as disciples of Christ the Teacher.

Doctor Know

Docility comes from the Latin verb docere, which means “to teach.” From docere we get the word “doctrine”—that which is taught. During the era of “doctrine-free” catechesis (now there’s an oxymoron for you!), some Church leaders and parents rightly were concerned that their children weren’t being taught, because teaching presupposes content. What was given to that generation—my generation—of young Catholics was many things (e.g., babysitting, sharing, collage-making), but it wasn’t doctrine.

From docere we also get the word doctor, which is another word for “teacher.” In the academic world, the most highly educated teachers earn their “doctorate.” In the Church, we have 33 doctors of the Church, from heavyweight philosophers and theologians like St. Thomas Aquinas to amazing spiritual guides like St. Teresa of Avila. The members of this select group are held up to the faithful as eminently reliable teachers of Christian doctrine.

And so we have the virtue of docility, which refers to our habitual attitude toward “doctors” who teach us “doctrine.” In other words, it’s about how teachable or coachable we are. As we will see, this virtue has specific applicability to our relationship to the Church, which is our mother and teacher. But it also applies to our ability to be taught in every sphere of daily living.

Docility is the mean between the extremes of, on the one hand, an excessive, prideful self-reliance, and on the other hand, a passive, cowering submissiveness. It’s about seeking and making use of wisdom wherever it is found. Bl. Mother Teresa famously searched for the “hidden Jesus” in everyone, especially the poorest of the poor. I think it’s fair to say that the docile person searches for the “hidden wisdom” in others.

Beyond Self-Instruction

There is an important distinction to be made between docility and studiousness. The latter, according to St. Thomas, is the virtuous pursuit of knowledge. It involves a right attitude toward the subject matter, an attitude that is appropriately serious, steadfast, and motivated. Learning merely to satisfy one’s curiosity or to gain the esteem of others does not reflect the virtue of studiousness.

But while studiousness is a very useful virtue, it can only take us so far on its own. Let’s recall, for example, the Ethiopian eunuch in the Acts of the Apostles. He was admirably studious, but he still needed instruction from Philip in order to come to a deeper, relational understanding of the Word of God (cf. Acts 8:26-40).

Docility thus complements studiousness, as it refers to the virtuous pursuit of knowledge from a teacher. Some knowledge is acquired through private experimentation and discovery, but a significant percentage of human knowledge is acquired through instruction. Therefore we must develop a proper attitude toward teachers—in other words, toward the instruments of instruction (the “doctor”) and not merely the subject matter (the “doctrine”).

Why does this matter? I mean, why is my relationship toward the “doctor” so important? So long as I somehow pick up the “doctrine,” what difference does the instrumentality make?

Dear Prudence

The answer is prudence, the pivotal virtue that disposes us to discern what is good in a real-life situation and to choose the best means for obtaining it. Prudence empowers us to make sound, practical decisions that help us achieve our goals.

In a specifically Christian context, prudence takes us even further, enabling us to give flesh to the gospel in our own lives as we strain forward to what lies ahead (cf. Phil 3:13).

Let’s briskly break down the three elements of a prudent act:

(1) deliberation—taking account of all the relevant principles, facts, alternatives, etc.

(2) judgment—coming to a sound decision

(3) execution—implementing the decision

Here’s an example: Zach makes a point of attending daily Mass. This week, however, his parish priest is on retreat, so there are no weekday Masses at his parish. What will he do this week?

First, there’s the deliberation. He considers the guiding principles, possibly with the guidance of his wife or spiritual advisor. He considers the immense value of weekday Mass and its meaning and place in his own life. He also takes into account that he’s not morally bound to attend daily Mass, especially on those extraordinary occasions when his parish doesn’t offer one.

Deliberation also includes fact-finding. Zach is relatively new to the area, so he finds out what other parishes are in his area. Perhaps he talks to friends who are more familiar with these parishes to find out more about them. He checks the Internet to confirm Mass times (so as to accommodate family and work responsibilities) and to see how far away the church is (what time would he have to leave in the morning to get there on time?).

Now Zach has all the information he needs to decide upon a course of action. He makes the prudential judgment to attend the 6:15 a.m. Mass at St. Isidore parish across town next week. Then he executes this judgment by setting the alarm for the appropriate time and going to St. Isidore for Mass each morning.

As this example shows, the deliberation process is crucial when it comes to making good decisions. Docility is the virtue that enables us to put into practice this biblical admonition: “Seek advice from every wise man” (Tb 4:18). It’s the ability to make good use of the experience, teaching, and authority of others, including the Holy Spirit, through the gift of counsel (cf. Is 11:2).

Again, we turn to Aquinas, who stresses that even the most learned of scholars (some might say, with some justification, ” especially the most learned of scholars”) need to be docile. Man is a social being and not completely self-sufficient. After all, we are not a bunch of “little, independent bodies” but rather part of the body—the Body of Christ, which enables us to appreciate our profound interdependence as children of God.

So we all need to be taught by others. The recognition of this universal truth proves one’s wisdom, not weakness.

Roadside Assistance

Let’s see how this understanding of docility plays out in the classic case of asking for directions.

My family is on the road, far from home, and we’re lost. My wife suggests that I stop and ask someone for directions. Assuming I’m docile enough to take this reasonable advice, we stop.

Now, the idea is not to seek just any information, but information that is reliable and trustworthy. Unfortunately, many people today are more likely to listen to favorite TV show hosts, media outlets, or even commercials than they are to the Church. But armed with prudence, if we come across people who are intoxicated, mentally challenged, or just visiting the area themselves, we realize that they’re not reliable sources of information for our purposes and we look elsewhere for assistance.

Now we finally come upon a local who’s a walking chamber of commerce. We happily are docile to him when it comes to the geography of the city, as he provides crucial details not found in our road atlas.

The last step is the execution. In our deliberation, we readily accept that this gentleman is a sound guide, and we make the prudential judgment to follow the directions he gives us. It’s now up to us to use these directions to get to our destination. If at some point along the way we decide to go a different direction, it will probably be to our own detriment. Whether it’s the result of pride or some other cause, our deviating from the directions we were given reveals that on some level we didn’t really trust our guide.

Docility is a hallmark of all successful people. In the area of sports, a docile athlete is a coachable, well-conditioned team player who, by listening to his coaches, gives his team the best chance to win. In the area of business, a docile leader is one who is able to learn from his or her colleagues and staff and is open to new and innovative ideas.

Docility is also a hallmark of successful (i.e., faithful) Catholics. We learn from Christ and the Church not to pass a test or for appearance’s sake, but so that we will be equipped to lead holy lives (cf. Eph 4:12).

Let’s briefly examine, then, three aspects of docility as the virtue specifically applies to our faith lives.

1. No Filters

Are we able to be taught by the Church, to be formed by the Church? Or do we impose our own will on the Church, striving to recreate the Church in our own image, deciding, for example, what moral teachings work for us? If the latter, then aren’t we putting Church teachings through our own personal approval process? Through conversion and the gift of faith, we recognize that we need to change, yet if we’re not docile, then we end up thinking we’re okay and that the Church has to change.

At the end of Matthew’s Gospel, our Lord instructs the apostles to teach the faithful (us) to “observe all that I commanded” (Mt 28:20). Let’s note that he said “observe” (or do or put into practice) all that he commanded, and not merely “know” or “learn.” He also said all, not most. How many teachings can we intentionally fail to observe and still claim to be faithful Christians (cf. Mt 7:21-23)?

We recognize the limitations of human teachers. However, in the case of our Lord, we are talking about a wisdom “greater than Solomon” (Lk 11:31). Indeed, He is the Son of God who alone has the words of eternal life (Jn 6:68), and this wisdom and authority has been entrusted to his Church. So when it comes to faith and morals, we have but one Teacher (hint: It’s not us and it’s not Oprah).

2. Spiritual Fathers

Christian docility is often tested when it comes to maintaining a proper attitude toward Church leaders. It’s one thing when our pastor explains a Church doctrine or affirms the grave sinfulness of contraception, homosexual activity, or abortion. But it’s another when he starts talking about matters of public policy like the environment, immigration, the economy, or national defense, where the Church offers principles but not definitive answers. And besides, there are bishops on both sides of these issues. We can’t be docile to all of them!

I addressed this issue in more detail in a prior This Rock article [“How to Talk to (and about) a Bishop,” January 2007], but I’ve found that we often make the matter seem more complex than it really is.

When it comes to established Church teaching in the area of faith and morals, docility leads us to accept and serenely live what the Church says with a “divine and catholic faith.” But when bishops apply Church teaching to contemporary issues, the issue isn’t infallibility or “magisterial note,” but rather our giving due respect to our spiritual father’s wisdom, which is likely the fruit of his personal intelligence and gifts, his assiduous study of Church teaching and other relevant sources of information, and his sacred office as an authentic teacher “endowed with the authority of Christ” (CCC 888).

It’s analogous to my own role as father of six children. Other than the times that I may be telling them official Church teaching, nothing that I tell my children is “infallible.” In fact, much of what I tell them is in the form of setting forth plans (“we’re going to go see Aunt Charlotte tomorrow”) or giving instructions (“after you mow the lawn, leave your tennis shoes by the back door”), for which “infallibility” doesn’t even make sense.

Despite my own failings as a father, I think it’s fair to say that I expect my children to take to heart what I tell them. Further, I think everyone would generally agree that my children do well to follow my instruction rather than talk back or disregard what I say. No one would say to them, “Do what your parents tell you only if you agree with them,” because then the presumption would be in favor of what the children want to do, rather than I what I think is best for them.

Similarly for Catholics, we recognize that our pastors’ application of Church teaching in some areas may on occasion be incorrect, but docility would lead us to give our spiritual fathers the benefit of the doubt, and to raise any concerns along those lines in a way that fosters communion in the Church.

3. Christ, Our Teacher

In the example of my asking for directions, I noted the possibility of my not acting upon the guidance provided by the local who was intimately familiar with the city. My not acting upon this guidance would reflect some doubt as to the reliability and trustworthiness of this individual. To some extent, that’s true of all human teachers. That’s why when we need to make an important decision, we’ll often consult more than one person, just as we’ll get a second opinion when contemplating a medical procedure.

But when it comes to finding a way out of the clutches of sin and attaining eternal beatitude, we have a sure guide: Jesus Christ, through the ministry of his Church, which is animated by his Holy Spirit.

In the end, docility is about moving beyond questions or doubts about Christ and about his Church. It’s about abandoning futile efforts to push the proverbial envelope or to otherwise rationalize a selective, partial commitment to Christ on our own terms.

Instead, it’s all about choosing the better part, sitting at the feet of the Teacher par excellence, striving to become saints.

SIDEBAR

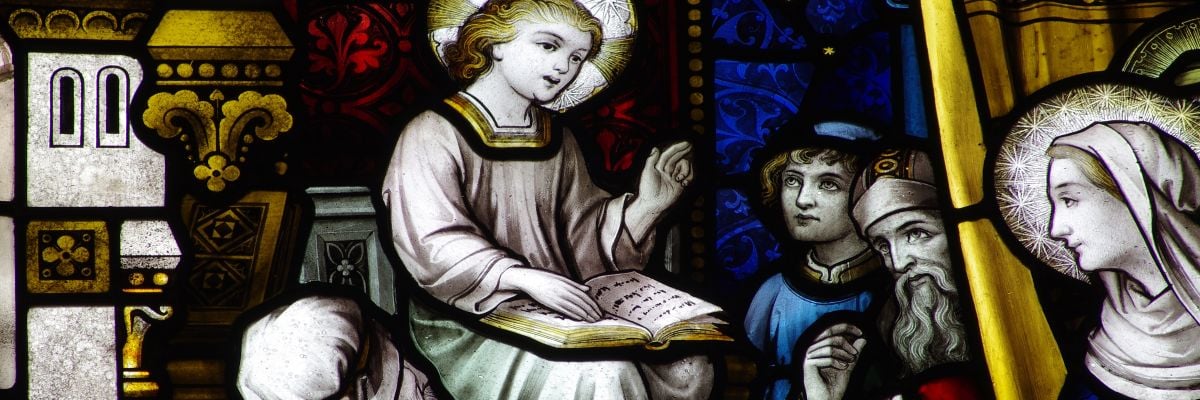

A Model of Docility

This humility, therefore, combined with the purity of heart we have mentioned, and sedulous devotion to prayer, disposed the mind of Thomas to docility in receiving the inspirations of the Holy Spirit and following his illuminations, which are the first principles of contemplation. To obtain them from above, he would frequently fast, spend whole nights in prayer, lean his head in the fervor of his unaffected piety against the tabernacle containing the august sacrament, constantly turn his eyes and mind in sorrow to the image of the crucified Jesus; and he confessed to his intimate friend St. Bonaventure that it was from that book especially that he derived all his learning. It may, therefore, be truly said of Thomas what is commonly reported of St. Dominic, father and lawgiver, that in his conversation he never spoke but about God or with God.

—Pope Pius XI, encyclical letter Studiorum Ducem on St. Thomas Aquinas (1923)