“Well done, good and faithful servant,” says the master in Jesus’ parable, who had traveled far away, leaving his men to engage in the risks of life. “Now enter into the joy of your master.” Those are the words the good Christian longs to hear. They are words that bespeak both a relationship of persons and the mystery of a God who risks his own wealth, so to speak, on the chance that we will seek him, and love him.

They are words that those who reduce mankind to matter cannot, on their own terms, understand. For man—made in the image of that God who can never be fully known, who reveals his love by giving us the freedom to seek him out—cannot find joy in any determinate thing. He longs not for contentment, as at a pleasant riverside, satisfied with a few easily obtained pleasures of the body, and waiting for death. He longs for joy. That is an experience no one can have alone. Joy wells up from the depths of love. It revels in the beloved, not as an object, but as an inexhaustible fount of what is good. Which is to say that joy is essentially personal, and therefore mysterious. What does that mean for our lives? For that, we turn to the most profound of Christian poets to illustrate.

Happy Meetings

The pilgrim Dante, once lost in a wilderness of sin, has been led by his fatherly guide Virgil down into the abyss of the damned. Sober and serious were the meetings with those souls lost forever, and stern was the counsel which the ancient poet gave the younger. At last, however, they enter purgatory, that realm where surprise is not dismay but wonder, shot through with an expectation of joys to come. Dante meets many an old friend in purgatory. Time and again they laugh, “What a fine thing it is that you are here!”—as good neighbors who meet by chance in a train station far from home.

Even Virgil is not shut out of such encounters. At one point, the ancient poet Statius, who has caught up with them as they walk, says that without the poetry of Virgil, all of his own verse would weigh “not a dram.” When he says it, Dante smiles, because unbeknownst to Statius, Virgil is walking right there beside him. Says Statius:

“Now be so good to tell me why—

so may your labor come to a good end—

you showed that little twinkle in the eye.” (21.112-14)

The twinkle in the eye here flashes faster than reason, faster than thought, because in a single moment Dante anticipates within his heart the joy and the wonder that Statius will feel, and the grateful love that Virgil will accept, when he reveals to Statius that

he who guides my eyes to look on high

is that same Virgil from whose lofty verse

you took the strength to sing of men and gods. (124-26)

All such meetings prepare Dante for the sight of his beloved, the blessed Beatrice who will be his guide unto the threshold of the vision of God in paradise. They are preambles of joy, just as the right reason that Virgil represents is a preamble to faith. And yet, as God is not a conclusion reached at the end of philosophical reasoning, but the three-Personed Being by whom we ourselves are persons, so joy—to be joy—is not reducible to a rational satisfaction, but plunges us into the depths of personhood, with all the surprises and turns of event that personal life entails. It is one thing to know a fact, but quite another to meet a person, and another still to meet a person in whom shines the light of God.

We know that a crystal of quartz has a certain structure, a fascinating one that has opened to us all the possibilities of the computer. But once we know it, we know it. Quartz will never meet us in a misty depot, looking upon us with eyes as distant and beckoning as the horizon. We can never come to an end of knowing a person, which is simply another way of stating that a person is that sort of creature made in the image and likeness of the unfathomable, self-revealing, and self-concealing God.

The Joy of Surprise

How, then, can we ever really be prepared for joy? It was exactly right that Statius should meet the poet to whom he owed his very conversion to Christianity. Yet the actual meeting, unexpected, even embarrassing, so overwhelms Statius with love that he falls to his knees and tries to embrace Virgil, forgetting for the moment that they are both shadows.

So Dante is not prepared to meet Beatrice. How could he be? And why should we expect him to be, seeing that it is joy he thirsts for, and not detachment from passion, or a stoical repose, or the realization of some quantum of utility? Indeed when Beatrice first appears, she does not appear at all, but is veiled. That veil is not simply a device for delaying Dante’s vision of the beloved. It too helps to manifest Beatrice’s beauty, just as the mist of morning allows us to look upon the sun:

I have seen, at the dawning of the day,

the orient heavens all a flush of rose,

while sweet serenity adorns the rest,

And the face of the sun is born in haze,

shadowed behind the mists that cool its powers

so that the eye may rest on it and gaze;

So too now from within a mist of flowers

that leapt like spray from the angelic hands

and fell within the chariot and without,

Under a white veil bound with olive bands

a lady appeared to me—her mantle, green,

her robes beneath, as red as living flame. (Purgatorio 30.22-33)

Nor will Dante simply behold Beatrice’s loveliness when she removes that veil. For another sort of veil—which shows and hides, which offers and retains—will always be with Beatrice, in part because Dante’s growth in vision and the spiritual life is incomplete, but also because union with the infinite God means that one can never reach the limit of knowing a fellow person in that communion or of being known by him. Familiarity, in paradise, breeds wonder. The Beloved above all is full of surprises. If you possess the Beloved, you possess the sureness of adventure. It is of the essence of joy that it be so.

Mechanical Man

If I am right, then we might define contemporary secularism as the cultural analogue to a machine: Imagine the vast and intricate stainless steel contraption used to print a little m on pieces of candy, hundreds at a time, indistinguishable one from another. There is nothing veiled about it. It is reducible to a blueprint, frank and simple. It is naked metal. It does what it is supposed to do. More to the point, it does not do what it is not supposed to do. It will not surprise. It will never, in a fit of gleeful revenge, turn against the man working the levers and print small letters all over his head. It will not muse about the past, when it was but a scattering of parts, awaiting assembly. It does not fear the future, the day of judgment, when all peoples that on earth do dwell shall have done with eating mass-produced candy, and shall instead make their own sweets and sing for joy.

It is only a machine. The trouble is that man does not only fashion machines for his purposes; he too often fashions himself after the purposes of his machines. That is especially true of the contentment offered by the secular state, and its subordinate machinery in the schools and what is tellingly called the entertainment industry. If man is conceived in mechanistic terms, then the best we can do with him is to make him predictable—to strip him bare of mystery—and engineer the public domain so that what is left of his personality will be reasonably content. What is offered to man instead of the genuine adventure of joy and abundance of life is a managed, planned satisfaction of material desires. Instead of the dangerous darkness of an embraced poverty—Jesus’ heartfelt appeal to the rich young man, or Francis’ brave tossing away of his clothes in the public square—we are offered toys: houses, cars, our own bodies buffed and polished. Instead of the risk of the quest—Dante descending to the underworld, Frodo setting out alone to Mount Doom, Galahad without a shield riding forth to see what eye has not seen, namely the mysteries of the Grail—we are offered the neural thrills of a world made safe for the tourist, a great amusement park with guard rails and cherry ice. Instead of the most fatal adventure of all, the emptying of oneself that Christlike love requires, we are offered the neural thrills of sexual planning, complete with a checklist for parts and function, and desperate techniques, old and wearisome, to stave away the boredom that sterilizes the soul of the practitioner in the act itself.

The secular world, on its own terms, can provide nothing else. More: Its central tenet, in our day, is that there is nothing else to provide. The only adverb it knows is only. Love is only sexual desire, and sexual desire is only an evolutionary development for continuing the species. Suffering is unfortunate and meaningless; wonder is naïve and childish; joy, a kind of excitation, transient, pointless.

One does not meet a machine. One can meet a person. That is almost the definition of what it is to be a person: to have a face to encounter. A single such meeting, especially if it occurs in the shadow of the God who veils himself from our sight that we might ever find what we seek and know the joy of both knowing him and not knowing him, should suffice to put the secularist reduction to rout. The machine can be reduced to our control, but a person always comes to us from without, and only as such can be the bringer of what bursts through all rationalist categories to fulfill our deepest yearnings within. The person can bring tears. The person can bring joy.

All Creation Speaks of Joy

Such was the case when Dante’s guide Virgil met Beatrice. He was, he tells us, among the souls in limbo, suspended in that twilight realm where reason knows only what reason can know, when suddenly a lady appears to him. And before she opens her lips, before she even tells Virgil who she is and why she has come, this exemplar of human reason “[begs] her for the grace of a command” (Inferno 2.54). Beatrice, like the joy she has not left behind, emerges suddenly from a hidden place, catching the mind of Virgil unawares. She tells him her wishes, which are themselves both veiled and made manifest in a story of courtly love, of ladies encountering one another in heaven, and of the poor lover lost upon earth. Then, says Virgil,

When she had finished speaking to me so,

she turned her glistening eyes all bright with tears,

which made me all the readier to go. (115-17)

Those tears, shining in a countenance turned aside for modesty, suggest a world of love, and Virgil responds accordingly, setting forth on a quest the like of which he had never known. In his heart’s longing for what can never be described as contentment—what the heart, much less the machinations of a technocracy, can never provide for itself—he will taste something of the joy offered to Dante. Virgil sees Beatrice. He does not see her smile; he does see her tears, the suffering for Dante that—far from impeding her joy—is a part of it, since it is a part of her love. It is a love so daring that it moves her to print her feet upon the floor of hell.

Where can we find such joy? The question is a paradox: It is not joy, if in some sense it does not rather find us, and seize us by the arm, laughing, “It’s you! How fine that is!” Yet God in his ebullient mercy has strewn intimations of joy about us, spangling the skies and the meadows and the seas with beauty. No saint need descend from heaven to show them to us. For the living God reveals himself at ease before us in the garden, and yet he hides; each mortal thing is an instance of his gift of being. They are, says the poet Hopkins, the grain whereby we can glean the Savior; they are present in their mysterious uniqueness, crying out, “What I do is me: for that I came” (“As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” 8). It is not only the “piece-bright paling” of the stars that enfold the Lord, but humble things too, like the glistening of loam after the horse has plodded through it, or “blue-bleak embers” falling in the hearth, gashing themselves, and revealing their hearts of gold and vermilion. Every creature, from the lowliest to the loftiest, is worthy of our admiration, can spring out at us with the revelation of the One who made them. In the glory that they give to God, and that we give to God on their account, all things are raised to the personal, all are crying out for the beholder, for one who will “meet” God in them, yet joyfully miss him too, as he exceeds infinitely all expectation. As Dante will put it, when he is given the grace to behold and not behold the unfathomable wisdom of the Creator:

I saw the scattered elements unite,

bound all with love into one book of praise,

in the deep ocean of the infinite;

Substance and accident and all their ways

as if breathed into one; and, understand,

my words are a weak glimmer in the haze. (Paradiso 33.85-90)

Hidden and Revealed

But we grow used to treating persons as if they were mechanisms, and the things of the world as if they were inert matter, manipulable according to our wish. That secularism which reduces one’s fellow man to a chemical machine lays bare the natural world, as if the blade of grass were no more than a sunlight-converter. In such a world turned wrong-side out—a world wherein Beatrice Portinari is just a young woman who married a banker and died young, or wherein the soil is bare but the foot is shod—we close off the possibility of joy, and our awareness of God recedes into numbness. The false familiarity whereby we think we know what a star is, or a wash of bluebells, is analogous to the demand, among some radical secularists, that God become the object of that same false familiarity, else we shall not believe in him. He must render up his existence and his secrets exactly as an insect preserved in formaldehyde and inspected under a microscope. Now this would amount to a lie, a self-contradiction. But suppose for the sake of argument God should submit himself to experimentation at our demand, by engineering, let us say, some spectacular show in the heavens, a concatenation of supernovas spelling out “I am here.” What would that prove, other than the existence of a Mister Zeus, far more powerful than we are, but not necessarily the Being whose essence it is to exist, and whose existence is itself a communion of love? It would bring us not joy but cowering fear, suspicion, and finally, alas, boredom.

Whenever God shows himself, he necessarily also veils himself, and if we isolate any such showing and take it as final and definitive, we risk falling before an idol, with presumption and despair soon to follow. God not only must remain infinitely beyond our power to grasp, but, by his love for us and our answering love for him, we cannot wish it otherwise, just as Dante could never wish to come to an end of the light of Beatrice’s beauty.

What God most reveals to us, then, by his concealment, is that he wants for man the freedom and the love that joy demands. He wants to shower upon us not simply a human life, which reaches its perfection in the rational attainment of human desires. He wants us to venture forth upon the divine life, the life for which human beings were made, which reaches its perfection in abandonment to the God whose life is freedom and love and joy. He conceals himself and reveals himself by giving us the liberty to love him or to refuse him; he is no divine puppeteer. But the freedom he wants from us is that which reflects his own self-humbling, creative act. It is the exuberant outpouring of a generous heart. It is the being-free with oneself that empties us of egotism, as we give ourselves over to the possibility of wonder, of surprise, of what we could not possibly plan, nor should we desire to. It is that greatness of heart that revels in being little before the mystery of another person, or that enlightens our minds by plunging our longings into the darkness of love. Take your household and go far away into the land I will show you, says God to Abram, and he goes. Take your staff, he says to Moses, and travel into Egypt, that land of bondage, and tell Pharaoh to set my people free—not that they might compass their small desires, but that they might worship their God in the wilderness. Yes, says Asaph the psalmist, the wicked enjoy their prosperity and prestige, while “their eyes stand out with fatness: they have more than heart could wish” (Ps 73:7), but it is all vanity, as insubstantial as a dream; to envy them is to be as witless as a beast. For God so loves us that he wants for his beloved the richness of unadulterated joy, that we might cry out, overwhelmed by the experience of his person, “Whom have I in heaven but thee? And there is none upon earth that I desire beside thee” (Ps 73:25).

We are made to know more than facts. We know persons: and most of all, we seek to know the Person who is himself truth. Dante shows us as much as he ascends the realm of joy, paradise, and beholds Beatrice growing ever lovelier, even as he learns that the mysteries of love exceed the comprehension of Mary and John and the most blessed of all the seraphim above. But let us return to our pilgrim at the top of purgatory mountain.

We Shall See Face to Face

Beatrice will not show him her face before he has repented of his sins. His heart needs to be cleansed. But even after he is washed in the purgatorial River Lethe and after she has removed her veil, there is more to see. It is not a matter of propositional knowledge, which can, at best, provide pleasure for the satisfaction of a rational mind. It is instead the knowledge-in-love that only comes from one’s encounter with that universe of meaning and event that is someone other than oneself. So the ladies named Faith, Hope, and Charity sing to Beatrice, begging her to reveal herself to Dante all the more, not by the eyes that see, but by the lips that tell of love:

“Turn, Beatrice, turn your holy eyes,”

so did they sing, “unto your faithful one,

he who has come so far to look at you!

Do us the grace for grace’s sake, unveil

your lips to him, that he may finally

behold the second beauty you conceal.” (Purgatorio 31.133-38)

Her response is so immediate that Dante will not describe it, except to say that what has already happened is beyond his power to describe:

Eternal radiance of living light!

Who ever sipped of the Castalian spring

or paled upon Parnassus’ wooded height,

Now would not find his mind a burdened thing,

attempting to portray you as you seemed,

where heaven had shaded you in harmony

And freely in the air your beauty gleamed? (139-45)

It is the only canto in the Divine Comedy that ends with a question—a rhetorical question, whose answer is a gleeful shake of the head. The Spirit leads us on from strength to strength, from adventure to adventure, from the glance of a beautiful woman, to her inexpressible smile. It is his work in us, and his play; his careful shepherding, and his risk-all gambit; the fidelity and recklessness of love, preparing us for joy. Who shall gainsay it?

SIDEBARS

What Is The Divine Comedy and Why Should I Read It?

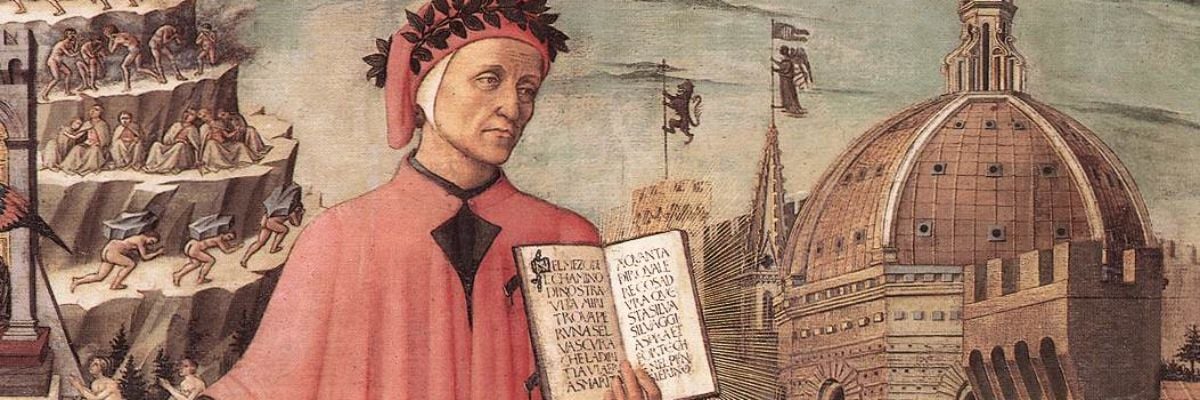

The Divine Comedy is, arguably, the finest work of Christian literature ever written and certainly the finest representation of Christian love. The author, Dante Alighieri, uses himself as a fictional character, and the story begins when Dante the pilgrim finds himself at midlife lost in a dark wood, having “left the straight way.” At the behest of Beatrice, who is Dante’s lifelong love and inspiration, the poet Virgil arrives to escort Dante on a spiritual journey. The journey takes him through the three realms of the afterlife: hell, purgatory, and heaven. Along the way, Dante learns about God’s love through his encounters with those in the afterlife. In hell he observes the consequences of love perverted, and he learns that every sin contains its own terrible punishment. In purgatory, he observes—and joins—the imperfect as they arduously seek perfection. He is then ready to see love perfected, to come face to face with God in heaven. Armed now with a much deeper understanding of God as Love, Dante returns to complete his earthly life.

—Editor

Christus Paradox

Jesus is the image of the invisible God; yet he is also the suffering servant, in whom beauty is submerged beneath recognition. Jesus mingles among the crowds, drawing to him such inconsiderable people as children and old women, and such smudged samples of humanity as tax collectors and whores, yet he betakes himself to the mountains alone to pray. He is transfigured before the eyes of Peter, James, and John, revealing the wonder of the Resurrection to come, yet he is naked and bloody on the cross, then laid in the tomb. The disciples on the road to Emmaus walk beside him and do not recognize him. Then they stop at an inn, and when he breaks the bread and blesses it—his broken and blessed body which he gives to his disciples to eat—they see him. They are stunned with wonder and joy, but he immediately vanishes from their sight. On the top of the mount of Bethany, he gathers his disciples about him, men of mingled faith and doubt. He is taken up to the Father, but in the very moment of his departure he commissions them to go forth to baptize all nations, assuring them that he will be with them until the end of the world.