1. Since the Bible says that contacting in the dead is the abominable sin of necromancy (Deut. 18:10–12), the intercession of the saints seems blasphemous to me.

This objection to the intercession of saints is an honorable and sincere one. It expresses a disposition that all Christians must have—refusing to do anything that takes away from the adoration that belongs only to God. When this objection is raised, you should affirm that if praying to saints takes away from one’s devotion to God, then it is a practice that should end at once. Expressing this to an evangelical Christian will help alleviate his presumption that you may not be as interested in serving God with single-heartedness.

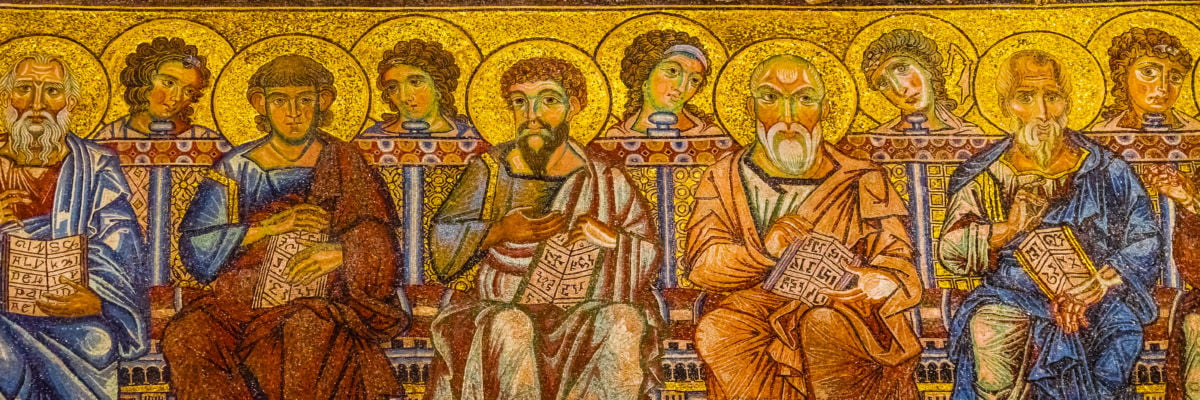

When the Bible mentions necromancy, it condemns the practice of conjuring up the dead, as Saul did through the witch of Endor in 1 Samuel 28. When Jesus spoke with Moses and Elijah during the Transfiguration, this was not necromancy. When David asked the angels of heaven to bless the Lord, this also was not offensive to God (Ps.103:20–21). Likewise, when a Catholic asks St. Peter to pray for him, he is not conjuring up a spirit from Hades in order to acquire secret knowledge. After all, those in heaven are “like the angels,” and are more alive than we are, since the Lord is “not God of the dead, but of the living” (Luke 20:36–38). So, if it does not offend God when a Catholic says “St. Peter, pray for me,” we should all rejoice that God has given us the gift of Peter’s prayers.

2. But if you pray to the saints you are worshiping them.

Whenever discussing a doctrine, it is always effective to define your terms. “Pray” is an Old English word that means simply “to ask.” In Protestant theology, the word has become synonymous with worship, but that is not the original use of the term.

Any time a Catholic utters a petition to a saint, it is taken for granted that it is a request for that saint to pray to God for them. For example, the “Hail Mary” contains the request, “pray for us sinners.” If you ask a person to pray for you, it proves that you do not think that he is God. What needs to be stressed here is that none of our prayers terminate in the saints, as if they had the power in and of themselves to answer prayers.

3. If I had a problem at work, why would I take it to the volunteers in the mailroom if I were friends with the CEO himself? After all, doesn’t the Bible say that Jesus is our one mediator (1 Tim. 2:5)?

The flaw in this objection is that it proves too much. For if Catholics should not ask those in heaven for their prayers since we can go straight to Jesus, then no Christian on earth should ask a fellow believer for his prayers. When one believer asks another for his prayers, it is not because God is too distant or callous to listen to him. On the contrary, God is so generous he has given the body of Christ such unity that each member can pray for the others. This is a great gift, for “the prayer of a righteous man has great power in its effects” (Jas. 5:16), and the angels and saints in heaven are inarguably righteous.

Though the Bible tells us that we must go to God in our necessities, it also encourages us to ask for each other’s prayers. After all, salvation is a family affair. Can the eye say to the hand, “I need you not?” Neither should we say that we don’t need the prayers of the rest of the body of Christ (on earth or in heaven).

Immediately after requesting that we pray for each other in 1 Timothy 2:1–4, Paul affirms that Christ is the one mediator. Again, let us define our terms. A mediator is one who comes between two parties with the purpose of uniting them. Christ played a role of mediation that only the God-man could, but Christians are still called to serve as mediators between Christ and the world. In no way does this diminish the unique work of Christ. On the contrary, it manifests it.

For example, Christ is our only high priest, but we are all called to be a nation of priests (1 Pet. 2:9). Christ is the only Son of God, yet we are made sons of God through adoption (Gal. 3:4). The Christian life consists in being conformed to Christ, and as Paul says, being “God’s fellow-workers” (1 Cor. 3:9) in his plan of salvation.

4. Aren’t the saints in heaven busy worshiping God?

Sometimes when discussing doctrines, it is helpful to take a step back and look at the objection from a different angle. So invite the person you are speaking with to imagine a man who spent 80 years on earth serving the Lord and praying fervently for everyone in need. After passing away, he walked across the clouds to the Pearly Gates. St. Peter checked the book, his name was there, and he was ready to enter. As he walked through the gates, he noticed a poem on a large sign that read, “Welcome to the Father’s house; we hope you enjoy your stay. In heaven, you may worship God, but you’re not allowed to pray.”

To think of those in heaven as unwilling or unable to pray for us is to have a grave misconception of heaven. It is not an isolated part of the body of Christ that exists without concern for the other members of the body who are still working out their salvation with fear and trembling (Phil. 2:12). Those in heaven surround us as a “great cloud of witnesses” (Heb. 12:1), and the book of Revelation teaches that the prayers they offer for us “saints” is an integral part of the eternal worship given to God.

John describes the heavenly worship in these terms: “The twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, and with golden bowls of incense, which are the prayers of the saints” (Rev. 5:8). The angels also play a role in bringing our prayers to God: “The smoke of the incense rose with the prayers of the saints from the hand of the angel before God” (Rev. 8:4). If intercession among members of the body of Christ on earth is “good and it is acceptable in the sight of God our Savior” (1 Tim. 2:1–4), how would such behavior not also be pleasing to God in heaven?

In the story of Lazarus and the rich man (Luke 16:19–31), the rich man shows concern for his family on earth, even though he is in hell. If a person in hell has such concern, and those in heaven are perfected in love and can finally pray with an undivided heart for the Church of God, how could they not be concerned about our salvation?

5. How can the saints hear our prayers?

Along with the concern about the “worshiping of saints” by praying to them, the question of their ability to hear us is among the most frequent of Protestant concerns. The book of Revelation is especially helpful in dealing with this, since it describes people in heaven who are aware of the happenings on earth (Rev. 6:11; 7:13–14). They have this capacity according to God’s designs and not of their own power. Paul alluded to this when he said, “Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood” (1 Cor. 13:12).

Those in heaven are part of the mystical body of Christ, and have not been separated from us by death. Christ is the vine, and we are the branches. So, if we are connected to him, we are inseparably bound together with them as well. Thus, the angels and saints stand before the throne of God, offer our prayers to him, and cheer us on as we run the good race.

If those in heaven are of no help to us, is it that they do not care, or does God forbid them to know of our toil and render them incapable of praying for us? Encourage the person you are speaking with to take this to prayer, asking the Father if this is truly his plan for the body of Christ.

6. There are one billion Catholics and 300 million Orthodox. If one in a hundred of these prayed a daily rosary, Mary would receive 689 million Hail Marys each day! So, even if she could hear the prayers, she’d have to be omniscient to comprehend them all. And where would she get the time?

Since Mary is in heaven, it is literally true that she does not have time to answer all the petitions—she has eternity. Time in the afterlife is not the same as it is here, and so this is not an insurmountable objection.

In regard to the number of petitions, if the number were infinite, then an omniscient mind would be required. So long as the number is finite, then the hearer requires a finite expansion of knowledge, which God could certainly grant to a glorified soul in heaven. While discussing this, you could point out that 50 people in an Internet chat room can communicate simultaneously from around the world. If modern technology can enable humans to do this, God is infinitely capable “by the power at work within us is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think” (Eph. 3:20).

When concluding any conversation—especially one on the intercession of the saints—it is always good to promise to pray for each other. Not only will this benefit both of you in the realm of grace, it will remind your friend that the body of Christ is a great gift to draw us near to God.