Mel Gibson’s movie The Passion of the Christ is the most theologically focused treatment of the suffering of Christ ever committed to film. Indeed, the film intends to be (and is) a theological statement on the true meaning of the sacrifice of Christ. I saw the movie opening night at a theater in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Everyone there had purchased tickets through a local Catholic college. The theater was filled with devout Catholics who—after listening for months to discussions in the media about the movie’s religious depth and its potential to cause conversions—were eager to at last have the film unfold.

Thirty minutes into the film the women to my left and right were weeping, and I caught the gentleman two seats away from me patting his eyes. The movie depicts the sufferings of Christ in detail. His suffering is deep, violent, grotesque, horrifying, and hideous. I am a devout Catholic who loves our Lord very much. I am also fairly emotional; I cry just hearing the first strains of the theme music for the movie Black Beauty. Gibson’s film disturbed me deeply but failed to move me deeply. I left the theater feeling extremely unsettled at the images I had just seen of our Lord’s physical suffering, images that will never leave my mind. But I was also unsettled by my lack of affective response.

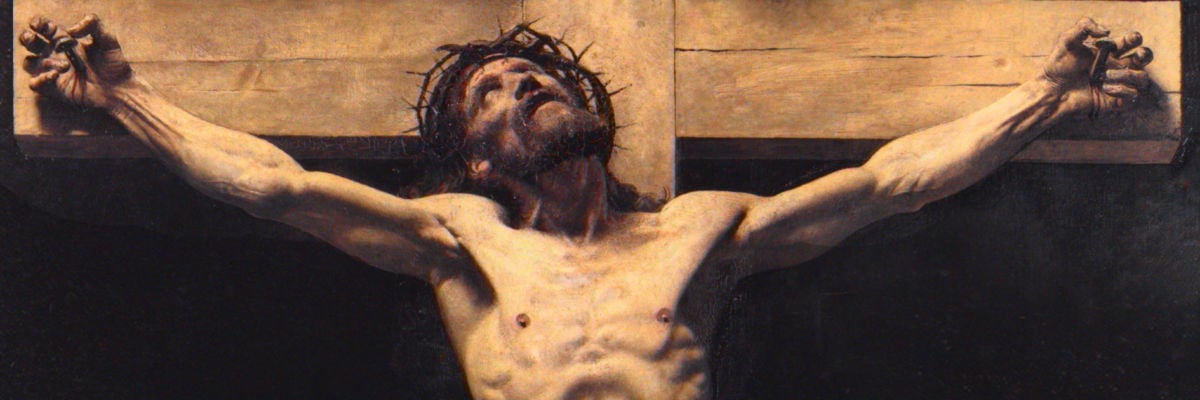

The Passion of the Christ is a deeply theological film. Its power as a film and as a piece of theological work is due to its choice of symbols, images, and gestures. From Jesus stomping on the head of the serpent to Mary kissing the feet of the crucified Christ, all of these symbols, images, and gestures are true portals through which the viewer is drawn into the truth of the person of Christ and his work of redemption. They include the unbelievable scene of Mary and Mary Magdalene wiping up pools of blood Christ shed at the pillar, Christ in agony who still hugs the cross when it is presented to him, Simon of Cyrene willingly carrying the cross with Christ when at first he refused to do so, Mary’s embrace of her Son when he falls from the weight of the cross, Veronica wiping the face of Christ and the ghostly imprint of blood left on her veil, and the literal shower of blood and water that gushes in seemingly endless streams from Christ’s side when he is pierced with a spear—blood and water that wash over the Roman soldier, causing his repentance. These images and others like them are what make this a work of genius and a film about Jesus unlike any other.

Yet the film is flawed. Now, I am not saying this is a bad movie or a failed movie. I think that, despite this flaw, The Passion still deserves to be called a masterpiece. As a form of art this film is raised up on a number of powerful, theologically grounded images. Any serious analysis of the film needs to be done in a theological context.

The one scene that everyone talks about most, from the average moviegoer to the most respected film critic, is Christ’s scourging at the pillar. This is no ordinary whipping, if such things ever can be ordinary. It is certainly one of the most—arguably the most—graphic depiction of violence ever put on film. Film critic Roger Ebert, a man who watches movies for a living, wrote: “This is the most violent film I have ever seen.”

Of course, one should not expect depictions of scourgings and crucifixions to be nonviolent. So where does the flaw lie? In a film loaded with powerful theological images, the scourging of Christ is the prime image. The viewer watches the beating, administered first with rods then with cat-o-nine-tails, in the minutest detail of flesh being flayed off the body of Christ by sadistic, cruel, mocking Roman goons. We hear or see every stroke. Blood is splashed everywhere. Even Christ’s tormentors notice they are sprinkled with it. The scene lasts several minutes. By the end of it, Jesus is a gaping wound from the top of his head to his feet. Every inch of his body bears a wound of some kind. There is not a space left on the incarnated God that is not affected by the sins of men.

This is Gibson’s theological point. I accept that the horrific violence, as the other images in the film, serves as a theological metaphor. Even the Roman soldiers’ great pleasure in causing Christ pain is theological metaphor, a commentary on sin and the desire of mankind to indulge the will contrary to God. In short, the Roman soldiers are a stand-in for all of us.

Gibson has explained in interviews that he wants to show the great love of God by the depth of the suffering Christ took on. But when Gibson dwells on the literal, physical suffering of Christ, the hideousness and grotesqueness of his presentation dominates the film. Some non religious film critics have voiced a legitimate complaint about the film’s violence.

I do not necessarily agree with the ultimate conclusions these critics make of the film. What I am saying is that their criticism of the violence in terms of the film’s overall spiritual and theological intent is credible. Once Christ’s whole body is turned into a wound, the viewer can never escape it: His mind becomes so absorbed by it that all of the other poignant, theologically profound gestures and signs in the film are eclipsed.

An argument can be made that the scourging even eclipses the crucifixion of Jesus. Yes, this is horrible too, but by then Gibson can make it more horrible than the scourging only by ratcheting up the violence with clever flourishes—and these flourishes, unlike the many extra-biblical theological images in the film, are not justified.

The crucifixion is bungled by the Roman soldiers (whom one would think by now would get it right) and the bungling, of course, causes Jesus additional pain. For example, the nails driven into Jesus’ hands slip out of pre-drilled holes. To fix the problem the cross is flipped over, with Jesus on it, so that the ends of the nails can be bent back and held in place. The bleeding, gaping sore of Christ’s body is now face-down on the earth. The weight of the cross is on top of him and the weight of his body pull against the nails.

Contrast this crucifixion with the one depicted in Franco Zeferelli’s 1977 movie Jesus of Nazareth. When Jesus finally makes it to Golgotha, the Roman soldiers obviously have done this dozens of times, and the actual execution happens with horrific efficiency. Christ is not even permitted to catch his breath and neither is the viewer. While Zeferelli’s crucifixion scene lacks the slow, graphic horror of Gibson’s, it is an equally legitimate and moving interpretation of Christ’s suffering without the additions needed to make it worse than the scourging.

Yes, the Passion of Christ is physical suffering, but it is much more than that. It is a theological and cinematic flaw to allow the physical suffering of Christ to overwhelm the viewer. Such emphasis on the physical torture of the body fails to serve the deeper theological complexity of Christ’s sacrifice and its meaning for us. Ultimately, the meaning of Christ’s sacrifice is not measured by the extent of his physical suffering.

Nevertheless, while the ultra-hyper focus on Christ’s physical suffering (albeit as a theological metaphor) is a flaw, Gibson’s The Passion is still a great, theologically rich movie. The movie is filled with eucharistic and Marian themes and demonstrates an appreciation for the meritorious sufferings of Christians in the economy of salvation. Gibson beautifully affirms the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and the Last Supper is the re-presentation of the sacrifice of Christ.

These truths are most powerfully communicated when Christ arrives at Golgotha and we are taken back to the Last Supper. A disciple brings unleavened loaves wrapped in linen to Jesus. The loaves are placed before Christ, who unwraps them. We are then taken back to Jesus at Calvary who is painfully “unwrapped”of his garments. The sacrificial body at Calvary is the same sacrificial body in the bread of the upper room.

Mary is an active participant in the salvific acts of Christ. She is the New Eve in enmity with Satan, who in the film is portrayed by an androgynous woman. The ancient enmity foretold in Genesis 3:15 is a central theme of the movie, demonstrated wonderfully when Mary follows her Son on one side of the Via Dolorosa while Satan follows on the other. Satan is the scoffer and derider of Christ’s mission whose presence is meant to demoralize and cause despair, while Mary is the supporter and the advocate of the Passion. The two foes even lock glances in a moral combat between good and evil, sin and redemption.

The first time we see Mary in the film Christ has been arrested, and she exclaims to Mary Magdalene and to us, “It has begun.” She is ready. Moreover, this is the Mary of the fiat mihi who, when she sees her Son arrested and taken to Pilate, announces, “So be it.” We enter into the Passion of Christ with her.

One of the most startling and moving scenes in the film is when Mary exclaims to her dying Son that she wishes to die with him. She kisses Jesus’ feet, and his blood is on her lips. With this image, Gibson seals the co-redemptrix theme. Russell Hittinger and Elizabeth Lev, in their insightful review, stated that in this image Mary is “the bride inebriated with the matrimonial wine.” This is an important image when one considers that Mary is called “Mother” blatantly by the disciples. Mary is the model of the Church and Mother of all who follow him.

From my reading, Gibson’s presentation of the character of Simon of Cyrene rarely has been discussed. But even here the viewer is treated to a wonderful theological feast. Simon just happens to be passing by on his way somewhere. The Gospels describe him as “coming in from the fields”—as if he were just coming home from a hard day’s work. He is confronted by the horrific scene of a beaten and bloody criminal sprawled on the ground—Jesus, completely exhausted, cannot carry the cross any further.

Simon intends to go his way, but, against his will, he is ordered by the Roman soldiers to take Christ’s cross. The character vehemently protests, and the nature of the protest is significant. He will not carry the cross of a criminal, as if to say, “This is beneath me—how humiliating and unfair!” But the Roman brutes coerce him into it. We see Simon take the cross only with great resentment and reluctance—but pick it up he does. Jesus manages to get up, and they carry it together. Jesus falls. The soldiers begin to kick and beat him mercilessly, and Simon orders them to stop. He takes pity on Jesus, and because of his intervention the soldiers relent. By the time he and Jesus get to Golgotha, the character of Simon has undergone a complete transformation.

Simon of Cyrene is given a cross he did not want, did not look for, and was loathe to embrace. And that’s just the way the spiritual life is: God sends crosses to us not of our choosing, and we hate it and complain about it. Some kinds of suffering are completely unexpected, like the sudden death of a loved one or a diagnosis of cancer. But God wills this for us, and we can either endure these sufferings with contempt or enter into them with Christ.

Through the literal carrying of the cross, Simon and Christ have become one. Simon has been allowed to enter into the Passion with him. When they finally get to the hill, Simon is hesitant to leave Jesus. He has to be coaxed away by the soldiers. As he backs away, he cannot take his eyes away from Jesus. At first Jesus was just some criminal. Now Simon is concerned about what will happen to him.

Carrying the cross is exhausting and painful for both Jesus and Simon. It is obvious that it is Simon who is aiding Jesus. Indeed, Simon says to Jesus to encourage him, “We are almost there now.” When Simon picked up the cross, he aided Jesus in his salvific work. Behind this scene is the passage from Paul: “Now I rejoice i n my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church” (Col. 1:24).

The Passion is filled with these sorts of theological surprises. It is the surprises that ultimately should draw our attention and absorb us, but because the film is dominated by the graphic physical torture of Christ, these great images cinematically are set in an orbit around a great red wound they are never able to compete with. This flaw makes the film less of a masterpiece, but a masterpiece it remains.

Much has been said about the movie’s potential to convert. It can convert many. The film can confirm faith and deepen love for Christ. It will probably bring Protestants (and even some Catholics) to a deeper appreciation for Mary and the Eucharist. Those who see the film will think about Jesus for many days afterward.

When Roger Ebert commented that The Passion was the “most violent film I have ever seen,” perhaps he was, despite himself, making a theological statement. The fact is that when we look at any depiction of the sacrifice of Christ—no matter how mild or graphic—man killing God is the most violent thing we will ever see.