Although I studied as much Hebrew as I could before my first trip to Israel, I ended up using it only at the Western Wall to tell people who mistook me for a local, “I’m sorry, I don’t speak Hebrew.”

Everywhere else I went, it would have been more practical to speak Arabic. For the past three years, in fact, the most popular name in Israel for baby boys has been Muhammad, the name of the prophet who founded the religion of Islam in the seventh century.

Muhammad claimed to have recorded a revelation from God in what is now called the Quran (sometimes written Koran; it means “recitation”), the sacred text of Islam. The fundamental claim of this revelation is that there is only God (Allah) and that Muhammad is his prophet or messenger.

Islam teaches that it is the completion of the revelation God gave in the Bible, and, accordingly, the Quran contains stories involving people such as Abraham and even Jesus (who in Arabic is called Isa).

Muslims are adamant that there is only one God and that God does not have a son. They say Jesus is not the Son of God but a prophet who, though he was born of a virgin, did not rise from the dead or proclaim himself to be divine. In fact, when our pilgrim group arrived at one holy site, we saw draped across from it a banner with Arabic verses from the Quran accompanied by this English translation:

O People of the Scripture, do not commit excess in your religion or say about Allah except the truth. The Messiah, Jesus, the son of Mary, was but a messenger of Allah and his word which he directed to Mary and a soul [created at a command] from him. So believe in Allah and his messengers. And do not say, “Three”; desist—it is better for you (4:171).

But how can that be true if . . .

There’s no reason to trust the Quran

The late Christian apologist Nabeel Qureshi said he converted from Islam because he asked himself, “What reason is there to stand by the koranic claims about Jesus when all the other records disagree? The Quran was written 600 years after Jesus and 600 miles away. The only reason to believe the Quran is an a priori faith in Islam.” In his analysis of all the nonbiblical references to Jesus, Robert Van Voorst concludes of the Quran, “Scholarship has almost unanimously agreed that these references to Jesus are so late and tendentious as to contain virtually nothing of value for understanding the historical Jesus” (Jesus Outside the New Testament, 17).

In other words, because the Quran is so far removed from the historical events it purports to describe, the only reason to trust its testimony would be if it were the inspired word of God. But Muhammad never claimed to have performed any miracles that would vindicate his prophetic claims, so there is no reason to believe the Quran is inspired.

The Quran even admits that no sign or miracle had been given to confirm Muhammad’s message. Sura (Quran verse) 13:7 says, “[T]hose who disbelieved say, ‘Why has a sign not been sent down to him from his Lord?’”, to which God tells Muhammad, “You are only a warner, and for every people is a guide.”

The Quran does offer one proof for the validity of its own testimony. Sura 2:23 says, “If you are in doubt about what we have sent down upon Our Servant [Muhammad], then produce a sura the like thereof and call upon your witnesses other than Allah, if you should be truthful.” In other words, “If you don’t trust the Quran, try to write something better.”

Muslim scholar Meraj Ahmad describes this “argument from literary eloquence” this way: “[N]o one has been able to imitate [the Quran’s] unique literary form. [What] makes the Quran a miracle is that it lies outside the productive capacity of the nature of the Arabic language and literature” (“Literary Miracle of the Quran”).

Does it follow that just because something can’t be imitated it must have a divine origin? The works of Shakespeare or Dostoevsky are unique and inimitable, but that doesn’t mean God dictated them.

Second, despite Muslim claims to the contrary, the Quran is similar to other medieval Arabic works and, in some respects, even deficient in comparison with them. According to the late Iranian author Ali Dashti:

The Qo’ran [sic] contains sentences which are incomplete and not fully intelligible without the aid of commentaries . . . illogically and ungrammatically applied pronouns which sometimes have no referent; and predicates which in rhymed passages are often remote from the subjects. These and other such aberrations in the language have given scope to critics who deny the Qo’ran’s eloquence (Twenty Three Years, 48-49).

The Quran contradicts scientific and historical facts

Some Muslim apologists claim that the Quran contains scientific truths that wouldn’t be discovered for centuries and so could have only come from divine inspiration. But this requires generous and creative imposition of modern scientific knowledge on vague quranic descriptions of the natural world—for example, when it is said that the quranic verse about how God “creates you in the wombs of your mothers, creation after creation, within three darknesses” (39:6) refers to the linings of the abdomen, uterus, and amniotic sac.

Despite the arguments some apologists make for its scientific accuracy, there are several verses that appear to contradict modern science. One of these is the Quran’s description of semen being created not from the testicles but “from between the backbone and the ribs” (86:7).

Texts like these do not necessarily disprove the Quran because, like the Bible, it might be a divinely inspired text that speaks through ancient worldviews and does not claim to assert modern scientific truths. But they do cast doubt on the idea that the Quran contains miraculous scientific knowledge that could have come only from God and that this is proof of its trustworthiness.

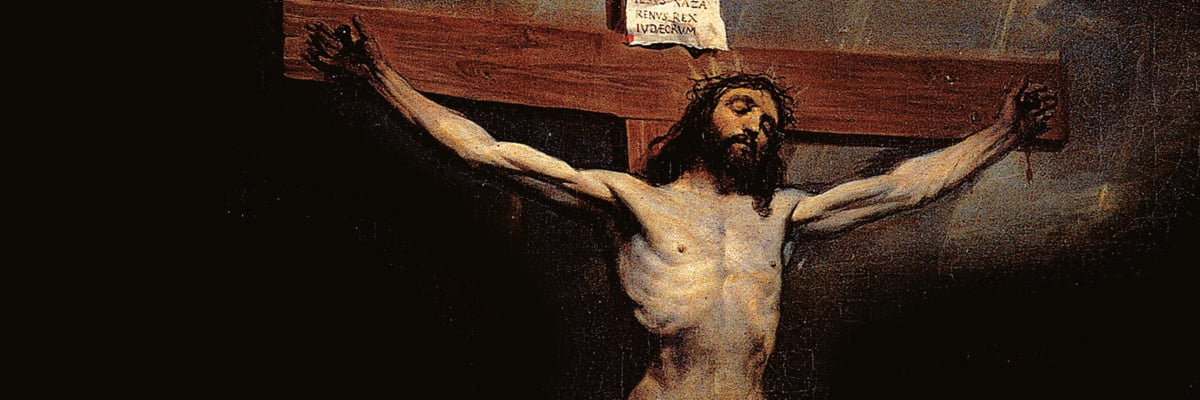

One of the most glaring inaccuracies in the Quran is not scientific but historical. Aside from mythicists who believe Jesus Christ never existed, Muslims are the only group who deny the well-accepted fact that Jesus died by crucifixion. The Quran says in Sura 4:157:

And [for] their saying, “Indeed, we have killed the Messiah, Jesus, the son of Mary, the messenger of Allah.” And they did not kill him, nor did they crucify him; but [another] was made to resemble him to them. And indeed, those who differ over it are in doubt about it. They have no knowledge of it except the following of assumption. And they did not kill him, for certain.

This should make us seriously doubt the reliability of the Quran, because almost everyone, including non-Christians, agrees that Jesus was crucified and died. Skeptical Bible scholar John Dominic Crossan denies that Jesus rose from the dead, but even he says “he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be” (Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography, 163).

In response to this evidence, most Muslims believe that God only made it appear that Jesus was crucified by putting someone who looked like Jesus on the cross in his place. In the seventh century, Mohammed’s cousin Ibn Abbas said this person was a Roman soldier named Tatianos or Natyanus. The fourteenth-century apocryphal Gospel of Barnabas claims that it was Judas Iscariot getting his comeuppance by being crucified in Jesus’ place.

But since, as we’ve seen, the Quran (not to mention medieval apocryphal gospels) was written too late to be a reliable historical source about Jesus, “and since there is no evidence that it is divinely inspired,” it follows that there are no reasons to believe its testimony when it contradicts the established historical record. This may be why some Muslim scholars claim Jesus was indeed crucified, but not “to death.”

Some modern Muslim apologists, such as Shabir Ally and the late Ahmed Deedat, claim that God allowed Jesus to be crucified but that Jesus was “rescued” from death, and so he wasn’t crucified in that sense. But it seems implausible that God would wait to “rescue” his beloved prophet until after he had been tortured, crucified, and entombed. Also, most translators of the Quran recognize that the text makes a distinction between killing and crucifixion—and that it denies that either of these things happened to Jesus. The key passage in Sura 4:157 is thus rendered in most translations, “they did not kill him, nor did they crucify him.”

The Quran supports the Bible

Even if we grant a Muslim apologist that the Quran is without error and completely trustworthy, there is still a problem with the claim that we should deny Christian doctrines such as the divinity of Christ. That’s because the Quran tells us that the Gospels (in Arabic, the injeel) are a part of divine revelation and that we should listen to that revelation too.

Sura 3:3 says, “He has sent down upon you, [O Muhammad], the Book in truth, confirming what was before it. And He revealed the Torah and the Gospel.” The Quran says that Jews who do not follow the Hebrew Bible are like donkeys who carry heavy books but do not understand them (Sura 62:5).

Christians also are exhorted to follow the New Testament, or, as Sura 5:47 puts it, “[L]et the People of the Gospel judge by what Allah has revealed therein. And whoever does not judge by what Allah has revealed—then it is those who are the defiantly disobedient.”

But this creates a contradiction because, as we saw in earlier chapters, the Bible teaches that Jesus is fully divine. In response to this problem, Muslim apologists claim the parts of the Bible that contradict the Quran are either misinterpreted by Christians or that they are textual corruptions added to the Bible later and so not a part of Allah’s original revelation. In order to bolster their argument, they often appeal to skeptical biblical scholars such as Bart Ehrman.

I have addressed at greater length in other works Ehrman’s claim about the Bible’s textual corruption. Here, let us focus on how Ehrman’s own scholarship undermines the Muslim claim that the New Testament teaches only Muslim doctrines.

One Muslim apologetics website claims that in John 20:28 the apostle Thomas is not calling Jesus “God,” even though he says, “My Lord and my God!” Muslims say Thomas is saying only that Jesus is “like God,” because one ancient manuscript called the Codex Bezae omits the Greek direct article ho before the Greek word for God (theos). The website claims:

The predecessor of the Codex Bezae and other Church manuscripts do not contain the article “Ho” (“The”) in their text (Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, 266). What this means is that this verse in its original form, if it is to be understood to be addressing Jesus (peace be upon him) himself, only addresses him as “divine” and not as the “Almighty God.” Thus, it is similar in meaning to the meaning conveyed when prophet Moses is described as being a “god” in Exodus 7:1.131.

So, according to this apologist, the absence of the definite article ho before the Greek word for God proves that Thomas addressed Jesus as a mighty prophet of God but not the mighty, true God himself. But this misuses Ehrman’s scholarship to support the view that the Codex Bezae records what John originally wrote.

Every other ancient manuscript records Thomas using the definite article and saying to Jesus, “The Lord of me and the God of me” [ho kyrios mou kai ho theos mou]. New Testament professor Brian Wright points out that the Codex Bezae “is an eccentric manuscript and regularly drops the article,” so it probably doesn’t reflect the original reading of John 20:28.

Ehrman conjectures that the scribe who copied the Codex Bezae intentionally left out the article ho and kept theos in order to thwart heretics who claimed that Jesus and the Father were the same person.

So, this is just evidence that an overzealous scribe in the fifth century incorrectly copied previous manuscripts, not that those manuscripts or the original text of John 20:28 does not affirm the divinity of Christ. Moreover, as Wright points out, even if the original text lacked the definite article before theos, he shows that the Granville Sharp Rule (see below) would apply, thus making it undeniable that Jesus is identified as theos, or the one God, in this verse. (“Jesus as Theos: A Textual Examination”).

In fact, the Muslim apologist’s reliance on Bart Ehrman will come back to haunt him, because elsewhere Ehrman states, “[T]he Gospel of John—in which Jesus does make such divine claims—does indeed portray him as God” (How Jesus Became God, 4).

If the Quran says we can trust the revelation God gave to St. John, and John describes Jesus as being God incarnate, then we should conclude that Jesus is not just a prophet that God sent to be a forerunner to Muhammad. He is instead the God who sent all the prophets and now comes to manifest himself to us—or, as the letter to the Hebrews tells us:

In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of his nature, upholding the universe by his word of power (1:1–3).

Sidebar 1

How Show Faith Can Be Said to Echo the Quran

Scholar Gabriel Said Reynolds argues that the Quran says only that the Jews did not kill or crucify Jesus. They thought they did, but it was really God who ordained that Jesus would be crucified, using the Jewish authorities to accomplish his will. This idea is even reflected in Acts 2:23, which says Jesus was “delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God” to be “crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men.”

Reynolds admits that this view of the crucifixion is a kind of litmus test for Muslim orthodoxy and that almost all Muslims hold that Jesus did not die on the cross (“The Muslim Jesus: Dead or Alive?” Bulletin of SOAS, vol. 72, no. 2 [2009), 237). This kind of exegesis, though, can be helpful in introducing open-minded Muslims to the reasonableness of the Christian faith by showing where it “echoes” the Quran.

This doesn’t mean that we should contradict Christian doctrine, only that we should remove as many unnecessary obstacles as possible to someone coming to believe in Jesus Christ as our God and Savior.

(See also “Islam and the Crucifixion” by Ali Ibn Hassan on catholic.com.)

Sidebar 2

The Granville Sharp Rule

This rule holds that when two singular common nouns are used to describe a person, and those two nouns are joined by an additive conjunction, and the definite article precedes the first noun but not the second, then both nouns refer to the same person. This principle of semantics holds true in all languages. For example, consider this sentence:

“We met with the owner and the curator of the museum, Mr. Jones.”

In the preceding sentence, the definite article the is used twice, before both owner and curator. The curator is obviously Mr. Jones, but the owner could be a different person. Did we meet with one or two people? Is Mr. Jones the owner of the museum as well as the curator? The grammatical construction leaves the question open. However, the following sentence removes the ambiguity:

“We met with the owner and curator of the museum, Mr. Jones.”

In the second example, the definite article the is only used once, before the first noun. This means that the two nouns, joined by and, are both in apposition to the name of the person. In other words, Mr. Jones is both owner and curator. The Granville Sharp Rule makes it clear that we are referring to the same individual.