In contemporary Catholic theology, a dogma is a truth that has been infallibly defined by the Church’s Magisterium to be divinely revealed.

However, the term has had many other meanings in the course of history. Originally, the Greek term dogma meant “opinion,” “belief,” or “that which seems right.”

By the first century, it often meant “edict,” “ordinance,” or “decree.” It is used in the New Testament for the decree of Caesar Augustus at the time of Jesus’ birth (Luke 2:1) and for decrees of the emperor Claudius (Acts 17:7). It’s also used for the legal requirements of the Mosaic Law (Eph. 2:15, Col. 2:14) and the decisions reached at the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 16:4).

Outside the New Testament, dogma retained its meaning of “opinion” or “belief.” The Church Fathers began using dogma to refer to the teachings of Christ, but they also used it for other teachings, including the views of philosophers and heretics.

It thus came to be a general term for “teaching” or “doctrine,” and for a time the “dogmas” of the Church were simply its authoritative teachings.

Opposed to the Church’s dogmas were heresies. Originally, the Greek term hairesis meant “opinion” or “choice,” but it came to refer to an opinion or choice contrary to official Church teaching. However, by the 1700s, more specialized senses of the terms dogma and heresy came to be employed, and these are the senses used today.

In the modern usage, a dogma is a truth that must be believed with divine and catholic faith. By contrast, “heresy is the obstinate denial or obstinate doubt after the reception of baptism of some truth which is to be believed by divine and catholic faith” (Code of Canon Law, can. 751).

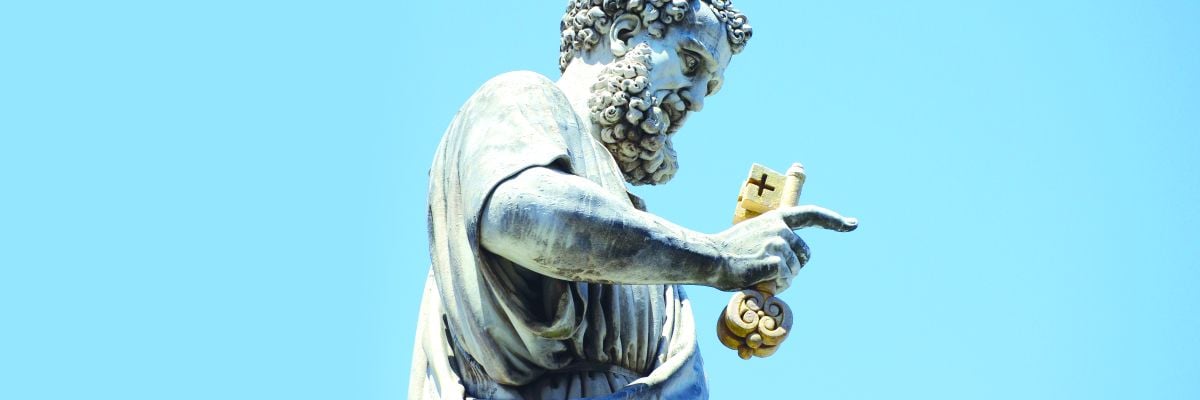

A truth calls for the response of divine and catholic faith if it is divinely revealed and the Church has infallibly defined it as such. Therefore, a dogma is any truth that the Church has infallibly defined to be contained in divine revelation—i.e., part of the deposit of faith handed down to the Church from Christ and the apostles.

Well-known examples of dogmas include the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary, which were infallibly defined as truths of divine revelation by Popes Pius IX and XII in 1854 and 1950, respectively.

It is important to note that the Church sometimes can exercise its infallibility without declaring a truth to be divinely revealed. In this case, the truth is not a dogma but merely infallible. Consequently, the Church does not say that it requires divine and catholic faith but merely that it is “to be definitively held.”

The Church has the ability to infallibly define certain non-revealed truths because they are necessary to properly defend and explain revealed ones. Without the ability to define such truths, doubt could remain concerning the divine revelation that Christ has given the Church.

For example, if a movement arose that claimed Pius IX was not a validly elected pope or that he did not infallibly define the Immaculate Conception of Mary, the Church could infallibly define both of these matters to protect the divinely revealed truth that Mary was immaculately conceived.

The Immaculate Conception itself is a dogma, but the facts that Pius IX was validly elected and that he defined the Immaculate Conception would rise only to the level of infallible truths. They could not be defined as matters of divine revelation, since they are not truths passed down from Christ and the apostles.

Church teachings (i.e., doctrines) fall into three classes: (1) those which the Church has authoritatively but not infallibly taught, (2) those which it has infallibly taught, and (3) those which it has infallibly taught to be divinely revealed. Only the third kind are referred to as dogmas in modern usage.

Since heresy involves the rejection of a dogma (either by obstinately doubting or obstinately denying it), heresy can only be committed when one rejects a teaching belonging to the third category. If one rejects a teaching belonging to the first or second category, the result is not heresy, though it may be gravely sinful.