Many atheists, neo-pagans, and other disbelievers of Christianity claim the story of Jesus Christ was borrowed from earlier mythologies. In recent years, a claim has been making the rounds that Jesus is based on the Egyptian god, Horus.

Who was Horus?

Horus is one of the oldest recorded deities in the ancient Egyptian religion. Often depicted as a falcon or a man with a falcon head, Horus was believed to be the god of the sun and of war. Initially he appeared as a local god, but over time the ancient Egyptians came to believe the reigning pharaoh was a manifestation of Horus (cf. Encyclopedia Britannica, “Horus”).

What about Jesus?

The skeptical claims being made about Jesus are not always the same. In some versions he was a persuasive teacher whose followers later attempted to deify him by adopting aspects of earlier god-figures, while in others he is merely an amalgamation of myths and never really existed at all. Both versions attempt to provide evidence that the Gospel accounts of the life of Christ are rip-offs.

In the 2008 documentary film Religulous (whose name is a combination of religion and ridiculous), erstwhile comedian and political commentator Bill Maher confronts an unprepared Christian with this claim. Here is part of their interaction.

Bill Maher: But the Jesus story wasn’t original.

Christian man: How so?

Maher: Written in 1280 B.C., the Book of the Dead describes a God, Horus. Horus is the son of the god Osiris, born to a virgin mother. He was baptized in a river by Anup the Baptizer who was later beheaded. Like Jesus, Horus was tempted while alone in the desert, healed the sick, the blind, cast out demons, and walked on water. He raised Asar from the dead. “Asar” translates to “Lazarus.” Oh, yeah, he also had twelve disciples. Yes, Horus was crucified first, and after three days, two women announced Horus, the savior of humanity, had been resurrected.

Maher is only repeating things that are and believed by many people today. Similar claims are made in movies such as Zeitgeist and Religulous and in pseudo-academic books such as Christ in Egypt: The Jesus-Horus Connection and Pagan Origins of the Christ Myth.

Often Christians are not prepared for this type of encounter, and some are even swayed by this line of argumentation. Maher’s tirade provides a good summary of the claims, so let’s deconstruct it, one line at a time.

Written in 1280 BC, the Book of the Dead describes a God, Horus.

In fact, there are many “books of the dead.” But there is no single, official Book of the Dead. The books are collections of ancient Egyptian spells that were believed to help the deceased on their journey to the afterlife. The title Book of the Dead comes from an Arabic label referring to the fact that the books were mostly found with mummies (cf. The Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology, “Funerary Literature”). Some of these texts contain vignettes depicting the god Horus, but they don’t tell us much about him.

Our information about Horus comes from a variety of archaeological sources. What we do know from the most recent scholarship on the subject is that there were many variations of the story, each of them popularized at different times and places throughout the 5,000-year span of ancient Egyptian history. Egyptologists recognize the possibility that these differences may have been understood as aspects or facets of the same divine persona, but they nevertheless refer to them as distinct Horus-gods (cf. The Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology, “Horus”).

Part of the problem with the “Jesus is Horus” claim is that in order to find items that even partially fit the life story of Jesus, advocates of the view must cherry-pick bits of myth from different epochs of Egyptian history. This is possible today because modern archaeology has given us extensive knowledge of Egypt’s religious beliefs and how they changed over time, making it possible to cite one detail from this version of a story and another from that.

But the early Christians, even if they had wanted to base the Gospels on the Horus myths, would have had no way to do so. They might have known what was believed about Horus in the Egypt of their day, but they would have had no access to the endless variations of the stories that laid buried in the sands until archaeologists started digging them up in the 1800s.

Another part of the problem is that the claimed parallels between Jesus and Horus contain half-truths, distortions, and flat-out falsehoods. For example . . .

Horus is the son of the god Osiris, born to a virgin mother.

The mother of Horus was believed to be the goddess Isis. Her husband, the god Osiris, was killed by his enemy Seth, the god of the desert, and later dismembered. Isis managed to retrieve all of Osiris’s body parts except for his phallus, which was thrown into the Nile and eaten by catfish. (I’m not making this up). Isis used her goddess powers to temporarily resurrect Osiris and fashion a golden phallus. She was then impregnated, and Horus was conceived. However this story may be classified, it is not a virgin birth.

He was baptized in a river by Anup the Baptizer, who was later beheaded.

There is no character named Anup the Baptizer in ancient Egyptian mythology. This is the concoction of a 19th-century English poet and amateur Egyptologist by the name of Gerald Massey. Massey is the author of several books on the subject of Egyptology; however, professional Egyptologists have largely ignored his work. In fact, his writing is held in such low regard in archaeological circles that it is difficult to find references to him in reputable modern publications.

In the book Christ in Egypt: The Horus-Jesus Connection (Stellar House Publishing, 2009), author D. M. Murdoch, drawing heavily from Gerald Massey, identifies “Anup the Baptizer” as the Egyptian god Anubis. Murdoch then attempts to illustrate parallels between Anubis and John the Baptist.

Some evidence exists in Egyptian tomb paintings and sculptures to support the idea that a ritual washing was done during the coronation of Pharaohs, but it is always depicted as having been done by the gods. This indicates that it may have been understood as a spiritual event that likely never happened in reality (cf. Alan Gardiner, “The Baptism of Pharaoh,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 36). This happened only to kings (if it happened to them at all), and one searches in vain to find depictions of Horus being ritually washed by Anubis.

Like Jesus, Horus was tempted while alone in the desert.

The companion guide to the film Zeitgeist outlines the basis for this claim by explaining, “As does Satan with Jesus, Set (aka Seth) attempts to kill Horus. Set is the ‘god of the desert’ who battles Horus, while Jesus is tempted in the desert by Satan” (p. 23).

Doing battle with the “god of the desert” is not the same as being tempted while alone in the desert; and according to the Gospel accounts, Satan did not attempt to kill Jesus there (cf. Matt. 4, Mark 1:12-13, Luke 4:1-13).

The relationship between Horus and Seth in the ancient Egyptian religion was quite different than the relationship between Jesus and Satan. While Seth and Horus were often at odds with each other, it was believed that their reconciliation was what allowed the pharaohs to rule over a unified country. It was believed that the pharaoh was a “Horus reconciled to Seth, or a gentleman in whom the spirit of disorder had been integrated” (The Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology, “Seth”). In stark contrast, there is never any reconciliation between Jesus and Satan in Scripture.

Healed the sick, the blind, cast out demons, and walked on water.

The Metternich Stella, a monument from the 4th century B.C., tells a story in which Horus is poisoned by Seth and brought back to life by the god Thoth at the request of his mother, Isis. The ancient Egyptians used the spell described on this monument to cure people. It was believed that the spirit of Horus would dwell within the sick, and they would be cured the same way he was. This spiritual indwelling is a far cry from the physical healing ministry of Christ. Horus did not travel the countryside laying his hands on sick people and restoring them to health.

He raised Asar from the dead. “Asar” translates to “Lazarus.”

The name Asar is actually a transliteration of the Egyptian name Osirus. As I mentioned earlier, Osirus is the father of Horus, and, according to the myth, he was killed by Seth and briefly brought back to life by Isis in order to conceive Horus. It was not Horus who raised “Asar” from the dead. It was his mother.

The name Lazarus is actually derived from the Hebrew word Eleazar meaning “God has helped.” This name was common among the Jews of Jesus’ time. In fact, two figures in the New Testament bear this name (cf. John 11, Luke 16:19-31).

Oh, yeah, he also had twelve disciples.

Again, this claim finds its origin in the work of Gerald Massey (Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World, book 12), which points to a mural depicting “the twelve who reap the harvest.” But Horus does not appear in the mural.

In the various Horus myths, there are indications of the four “Sons of Horus,” or six semi-gods, who followed him, and at times there were various numbers of human followers, but they never add up to twelve. Only Massey arrives at this number, and he does so only by referencing the mural with no Horus on it.

Yes, Horus was crucified first.

In many of the books and on the websites that attempt to make this connection, it is often pointed out that there are several ancient depictions of Horus standing with his arms spread in cruciform. One can only answer this with a heartfelt “So what?” A depiction of a person standing with his arms spread is not unusual, nor is it evidence that the story of a crucified savior predates that of Jesus Christ.

We do have extensive evidence from extra-biblical sources that the Romans around the time of Christ practiced crucifixion as a form of capital punishment. Not only that, but we have in the Bible actual eyewitness accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion. On the other hand, there is no historical evidence at all to suggest that the ancient Egyptians made use of this type of punishment.

And after three days, two women announced Horus, the savior of humanity, had been resurrected.

As I explained before, the story of the child Horus dying and being brought back to life is described on the Metternich Stella, which in no way resembles the sacrificial death of Jesus. Christ did not die as a child, only to be brought back to life because his grieving mother went to the animal-headed god of magic.

The mythology surrounding Horus is closely tied with the pharaohs, because they were believed to be Horus in life and Osirus in death. With the succession of pharaohs over the centuries came new variations on the myth. Sometimes Horus was believed to be the god of the sky, and at other times he was believed to be the god of war, at other times both; but he was never described as a “savior of humanity.”

Combating the never-ending list of parallels

If you do an Internet search on this subject, you will come across lists of supposed parallels between Jesus and Horus that are much longer than Bill Maher’s filmic litany. What they all have in common is that they do not cite their sources.

Should you encounter people who try to challenge you with these claims, ask them to explain where it is they got their information. Many times you will find that they originate with Gerald Massey or one of his contemporaries. Sometimes they have been repeated and expanded on by others. But these claims have little or no connection to the facts.

You should challenge the person making the claim to produce a primary source or a statement from a scholarly secondary source that has a footnote that can be checked. Then make sure the sources being quoted come from scholars with a Ph.D. in a relevant field, such as a person who teaches Egyptology at the university level.

Due to the mass of misinformation on the Internet and in print on this subject, it is important to respond to these claims using credible sources. Fortunately, there are many good books on Egypt and Egyptology in print. But there are also bad ones, so make sure to verify the author’s credentials before purchasing them.

The study of ancient Egypt has come a long way since its beginning in the 1800s, and new discoveries are being made even today that improve upon our understanding of the subject. It’s safe to say they will do nothing to bolster the alleged Jesus-Horus connection.

The Horus mythology developed over a period of 5,000 years, and as a result it can be a complex subject to tackle. But you don’t have to be an Egyptologist to answer all of these claims. You just need to know where to look for the answers—and to be aware of the claims’ flawed sources.

Sidebar 1:

Sidebar 1:

A brief history of modern Egyptology

Modern Egyptology really begins with the French campaign in Egypt and Syria initiated by Napoleon Bonaparte around 1798. Among other things, the French established a scientific exploration of the region.

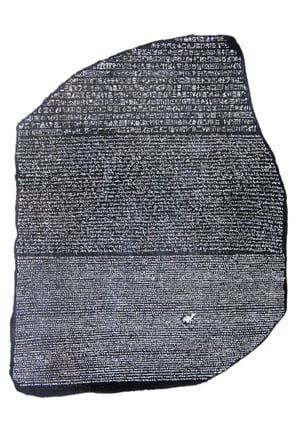

In 1799, a soldier named Pierre-Francois Bouchard discovered the Rosetta Stone, which contained a bilingual text that eventually led to the translation of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Prior to this, our knowledge of ancient Egypt’s 5,000-year history was limited to what was known through the writings of pre-Christian Greek historians such as Herodotus and Strabo.

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone led to a renewed interest by the Europeans in all things ancient Egypt, commonly referred to now as “Egyptomania.” It was not until nearly a century later that Egyptology as an academic discipline began to come into its own. Since that time, we have a much better understanding of ancient Egyptian history and culture.

Sidebar 2:

Sidebar 2:

Massey scholarship

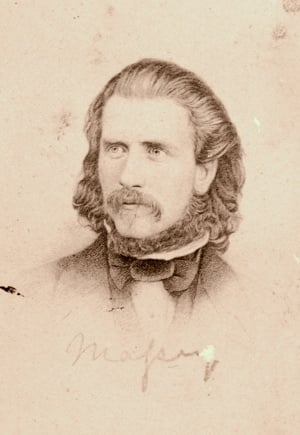

When researching the supposed Egyptian influences on Christianity, inevitably one comes across the name Gerald Massey. Massey was an English poet and amateur Egyptologist who lived from 1828 to 1907. He is the author of three books on the subject: The Book of the Beginnings, The Natural Genesis, and Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World. Because his books represent some of the earliest attempts to draw comparisons between the Christian and Egyptian religions, other writers attempting to draw these comparisons frequently cite them.

One recent example is the book Christ in Egypt; The Horus-Jesus Connection by D.M. Murdoch. In it the author states: “This present analysis of the claims regarding the correspondences between the Egyptian and Christian religions is not dependent on Massey’s work for the most part,” yet she devotes an entire chapter of the book to defending the authenticity of Massey’s scholarship (something she does not feel called to do for anyone else she quotes in her book) and thereafter adopting many of the same comparisons.

Critics of Massey’s work often point out that he had no formal education in the area of Egyptology. While this is a valid criticism, I think it is also important to point out that the study of ancient Egyptian religion has advanced far beyond what was known in the 19th century. Not only is much of Massey’s scholarship built on wild speculation, it is also the product of an academic discipline still in its infancy.