In a recent article, I discussed the penitential character of Advent and noted the difficulty of maintaining this while the world seems determined to make the season an anticipatory celebration of Christmas. A similar problem arises in the context of the beginning of Lent—and goes back much farther, historically.

Fat Tuesday Versus Lent

Lent is the Church’s major penitential season. The degree of rigor has varied over the centuries, but in the 1917 Code of Canon Law (CIC), every day of Lent (except Sundays) was a fast day, when we could eat only one full meal and two light meals. (On most of these days, eating meat was permitted.) Earlier in the history of the Church, the Faithful would abstain from not only meat during Lent, but also even eggs and butter.

In both the 1917 Code and the current 1982 Code, abstinence from meat is required on Fridays throughout the year (except for holy days of obligation in 1917, and solemnities in 1982). The possibility of waiving this was given to bishops’ conferences in 1966. Since then, many have indeed waived it, including the conference of the USA. (Interestingly, perpetual Friday abstinence was brought back in England and Wales in 2011.) In the current Code there, are only two fast days in the year: Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

Keeping in mind the older rules, Lent was historically a very serious period of penance, and the custom arose of having a celebration immediately before it started on Ash Wednesday. This day, Tuesday, has variously been called Shrove Tuesday, from the old English word for Confession (shrift, with the verb shrive), or Fat Tuesday (in French, Mardi Gras). The celebration could extend to a period of time before the Tuesday, with a whole period of Carnival—literally, a “farewell to meat.” In the context of the Medieval discipline, these were the last days, until Easter, during which meat and oil could be consumed.

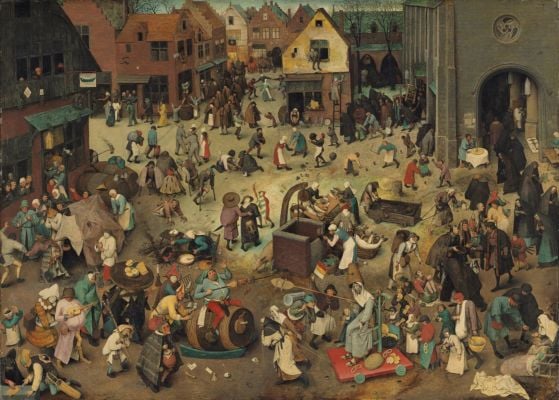

In some places, the fond farewell to meat could become a fond farewell to debauchery, satirized by the Dutch artist Bruegel’s 1559 painting “The Battle of Carnival and Lent.” The misbehavior of the Carnival in Venice was also notorious, giving us the tradition of carnival masks, which hid the identities of revelers and protected them, they hoped, from repercussions.

Fat Tuesday as a Catholic Tradition

These are venerable traditions of Catholic culture, certainly, but not ones we should be maintaining or reviving. In any case, things have moved on. Carnivals no longer conclude with a period of penance: The world wants to party, but not to clean up the mess afterward.

At the same time, it is not quite correct to say that the modern world has given up on penitential practices. On the contrary, as Fulton Sheen noted, often the world picks up what the Church discards. He gave the example of the decline of devotion to the rosary just when hippies and New Agers adopted the prayer beads of other religious traditions. Equally, at the very time when the Church’s penitential practices were being whittled down to nothing, on the basis that they were incompatible with modern life, the developed world was swept by dieting fads, and the ideal body, exposed to public view by new fashions, demanded iron self-discipline to maintain. A different kind of self-discipline is required to avoid feeling a bit of failure for not living up to these spartan standards.

Fasting and abstaining, in the past, were practices that pretty well everyone could maintain—the sick and certain others were always exempted. These practices united Catholics: something that everyone could complain about equally. The new standards of health and beauty, by contrast, are elitist by design: they are ways that the elite can remind us of their status.

There is nothing wrong with reminding ourselves of the imminent start of Lent with a bit of fun and special foods. As noted, the day before Ash Wednesday is called “Shrove Tuesday,” connecting it with the commendable practice of going to confession before the start of Lent. Preparation for Lent, itself a period of preparation for Easter, may sound unnecessary, but preparation for a period of penance is indeed a good idea. In the calendar of the pre-Vatican II 1962 Missal, and in the Calendar of the Ordinariates for Anglican converts, Lent is preceded by three Sundays of the season of Septuagesima, “pre-Lent,” when fasting is not required but the violet of penance is adopted as the liturgical color. This puts Fat Tuesday into context as the culmination of a period of preparation for Lent, when in past centuries stocks of fats would be used up.

In the English-speaking world, Shrove Tuesday has long been marked in a culinary way by pancakes, which must be the most modest kind of party food imaginable. In my childhood in the U.K., we used to eat thin English pancakes rolled up with lemon juice and a sprinkling of sugar; these would appear even in non-Catholic schools on “Pancake Day.” Sliced bananas, ice cream, and hot chocolate sauce have, as they say on social media, now “entered the chat,” but if you are making them at home, a huge amount of the fun is tossing them, to cook them properly on both sides. You have to not worry too much about the ones that get away—they are very cheap to make—and devote yourself seriously to practicing this noble art, remembering that in this, as in so much of what makes Catholic culture fun, you are entering into the spirit of the liturgical year.

Why We Party . . . and Why We Fast

A party that goes on all year round ceases to be a party and ceases to be fun. A celebration is by definition something that rises up above the level of the ordinary. The lower the troughs, the higher the peaks can rise in comparison. The penances of Lent are essential to the joy of Easter, and the mortifications of Lent can themselves be consoled by the way one marks Fat Tuesday. Human beings are not machines, working best at an even temperature with a perfectly steady intake of calories. We are organisms designed for feast and famine, for joy and woe. As William Blake expressed it,

Joy & Woe are woven fine,

A Clothing for the Soul divine:

Under every grief & pine,

Runs a joy with silken twine.