Imagine the Protestant reaction to news that the pope authorized a translation of the Bible that added words and altered the contents to make Scripture appear to support Catholic theology. Protestant apologists would be dancing in the streets because they would finally have objective proof that the Catholic Church believes it is superior to the written word of God.

Better still—what if Catholicism’s very origin could be traced to such actions? The news would likely be the last topic anti-Catholic bloggers ever posted, for their services would no longer be needed.

Incredibly, something very close to such a scenario actually happened in the Church’s history—but it was a rebellious monk, not an unfaithful pope, who committed the acts. His name was Martin Luther.

As is well known, the two foundational Protestant doctrines are those of sola scriptura (Scripture alone) and sola fide (faith alone). The importance of these doctrinal innovations is seen in their labels as, respectively, the formal and material causes of the Reformation. Sola scriptura is the methodological doctrine of the Reformation, for Protestantism is said to be founded on Scripture alone (as opposed to religious tradition). Sola fide, the idea that salvation is by faith alone (apart from good works) is the primary doctrinal teaching to come out of sola scriptura.

Protestantism’s principal founder, Martin Luther, is famous for claiming that if this “doctrine of justification is lost, the whole of Christian doctrine is lost.” He also challenged the authority of the Church by saying,

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.

The problem, though, with asserting sola fide based on sola scriptura is that the idea that justification is by faith alone is not only not stated in Scripture—it directly contradicts what Scripture states.

James 2:24 is the only verse in the Bible that uses the phrase “faith alone”—and it says that people are “justified by works and not by faith alone.” This is one reason why Martin Luther wanted the epistle of James removed from the Bible. Luther himself admitted that sola fide contradicts James—even claiming, “I do not regard it as the writing of an apostle.” In the pre-1530 version of his Preface to the Epistles of St. James, Luther held that James “is flatly against St. Paul and all the rest of Scripture in ascribing justification to works. . . . He mangles the scriptures and thereby opposes Paul and all Scripture.”

Luther then issued the following challenge: “To him who can make these two agree I will give my doctor’s cap, and I am willing to be called a fool.”

Thus, instead of adjusting his theology to fit Scripture, Luther’s solution was to relegate the book of James to the canonical cheap seats, declaring flatly in his Preface: “I will not have him in my Bible to be numbered among the true chief books.” Indeed, Luther’s advice was that they “should throw the epistle of James out of this school, for it doesn’t amount to much.” And of course, Luther famously declared James to be an “epistle of straw.”

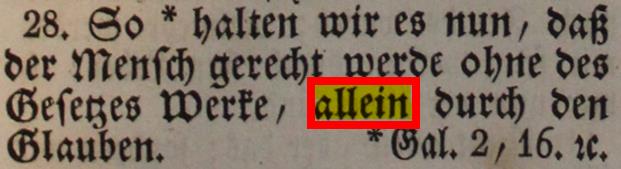

Romans 3:28 was the closest verse in Scripture that seemed to prove Luther’s novel idea concerning justification. However, it lacked the all-important word alone that would have makes Luther’s sola doctrine true. Once again, though, rather than adjust his theology, Luther adjusted the Bible. In his translation of Romans, Luther added the word alone to verse 3:28 (making it say “man is justified by faith alone apart from the deeds of the law”) in order to make it appear that he had biblical support.

When challenged about this rather transparent translational bias, Luther responded: “If your papist wants to make so much fuss about the word sola [alone] tell him this, ‘Dr. Martin Luther will have it so, and says that a papist and an ass are the same thing.’”

It seems, then, that Luther himself was guilty of doing the very thing he accused the Catholic Church of doing: elevating his theology above the Bible. In his attempt to justify (pun intended) his doctrine of sola fide, Luther both mistranslated the content of, and modified the canon of, Scripture—the one authority he claimed to stand upon while rebelling against the Church’s teaching.

Ironically, then, sola fide turns out to be a good argument against sola scriptura and vice-versa. For if sola scriptura allows one to hold to a doctrine that verbally contradicts Scripture and that requires both additions and subtractions to Scripture in order to appear scriptural, then anyone (including the Church) can claim agreement with sola scriptura.

What, then, of Protestantism?