At a recent speaking event I was asked whether it is acceptable to remove life support or if we have “to do everything we can” to keep a person alive. I summarized the Catechism’s explanation that it can be “legitimate” to discontinue “medical procedures that are burdensome, dangerous, extraordinary, or disproportionate to the expected outcome” (2278).

A man in the audience then asked me, “But specifically what is extraordinary care?”

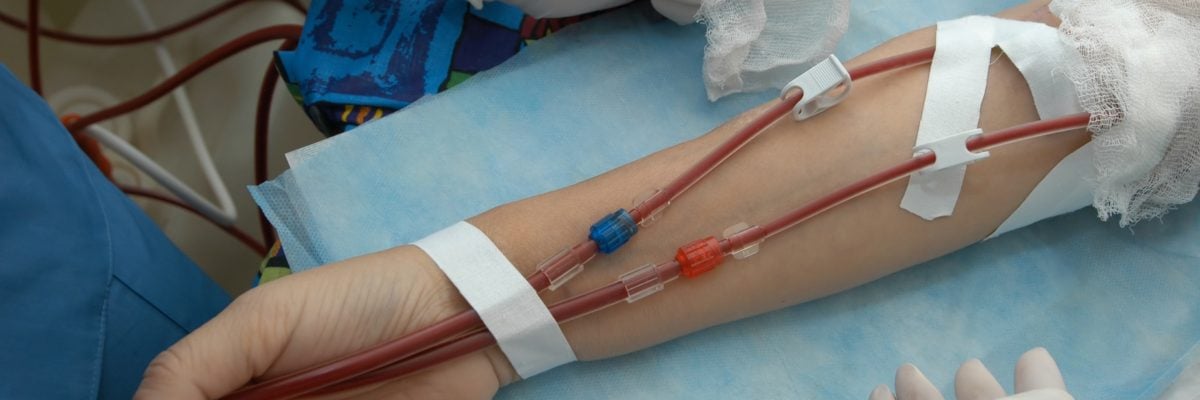

He had been following the debate over California’s Proposition 8, which has called attention to the high costs of kidney dialysis, and wanted to know if taking someone off dialysis was acceptable or the equivalent of murder.

Apart from costs, dialysis can also impose a significant physical burden on the patient, so I understand the dilemma people face when trying to decide if it should be removed. In order to answer that dilemma we have to understand the nature of what many people call “extraordinary care.”

Most ethicists use the term disproportionate rather than extraordinary to refer to treatments that patients can ethically refuse. According to the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, “Disproportionate means are those that in the patient’s judgment do not offer a reasonable hope of benefit or entail an excessive burden, or impose excessive expense on the family or the community.”

I’ve heard some Catholics say that extraordinary care refers to “things like dialysis and ventilators, that use machines to keep you alive.” That can be true, but it isn’t always true. Some use of “machines” would not be extraordinary care. A healthy twenty-five-year-old, for example, might need a ventilator for a few days in order to recover from a traumatic accident; in this case the burdens of treatment are proportionate to the benefit provided to the patient.

Surgery is also an “extraordinary” medical intervention but it isn’t always disproportionate. Some newborns are diagnosed with a blocked intestine that would result in death by starvation were it not fora simple, relatively low-risk surgery. In 1982 the famous baby Doe case involved a couple who considered such a surgery disproportionate and chose to let their baby starve to death instead. In this case, the child was deprived a procedure that would have provided proportional care, but its life was considered “not worth living” because of a Down syndrome diagnosis.

Conversely, some seemingly “ordinary” interventions actually involve disproportionate care. For example, when a patient is near death it may be painful for him to swallow, he may have a total loss of appetite, and his body may not be able to digest food. In these cases, withholding the ordinary care of food and water is not done to starve the patient to death but to make his inevitable death less painful. That’s why the Catechism says the refusal of “extraordinary care” involves a “refusal of ‘over-zealous’ treatment. Here one does not will to cause death; one’s inability to impede it is merely accepted.”

So what about dialysis?

A dialysis machine monitors the transfer of dialysate, a solution used to purify a patient’s blood and deliver electrolytes into his body when a patient’s kidneys are too damaged to perform this function themselves. It’s a time-consuming treatment that requires patients to follow strict dietary protocols and often leaves them in a fatigued and nauseated state. Dialysis can also lead to frailty, cognitive impairment, and lack of motor functioning, and so contribute to falls. Long-term dialysis use has also been connected to internal bleeding and serious bacterial infections. According to one study, the expected survival time of a patient on dialysis is one-third that of a patient receiving a kidney transplant. But a patient whose kidneys are not functioning can only live for a few weeks if dialysis treatment is stopped.

Just as we saw with ventilators and feeding, we can’t immediately say whether this particular treatment is always disproportionate because we must take into account the patient’s unique circumstances. In some cases, dialysis would involve disproportionate care that could be refused. A patient whose body is beginning to shut down and is experiencing gastric infections and bleeding from the procedure may feel the benefits are no longer worth the financial and physical burdens that accompany it. According to bioethicist Fr. Tad Pacholczyk:

Dialysis can prolong and save a patient’s life, but can also impose significant burdens. Depending on the various side effects and problems associated with the procedure, and depending on how minimal the benefits may be in light of other medical conditions the patient may be struggling with, it can become reasonable, in some cases, to discontinue dialysis.

But in cases of otherwise healthy individuals, the removal of dialysis may be unethical. A few years ago a woman known only as “C” tried to commit suicide through an alcohol overdose but only succeeded in destroying her kidneys. She was placed on dialysis and successfully appealed to the courts to have her care removed so that she could be “allowed to die.”

In this case, C’s decision to refuse dialysis was not motivated by a careful analysis of the benefits and burdens associated with the treatment, but by a pre-existing desire to end her own life.

And so the answer to the question, “Is this treatment disproportionate?” (be it artificial nutrition, dialysis, a ventilator, etc.) cannot be based solely on whether a machine is helping someone to live. Neither can it be made on the arbitrary judgment that some lives are “worth living” and others are not. Instead it must be based on whether the treatment provides benefit to the patient and if that benefit is proportional to the treatment’s financial, physical, and emotional burdens.

If you or a family member is weighing these issues in order to determine if a treatment should be discontinued, I recommend speaking with an ethicist at the National Catholic Bioethics Center. Fr. Pacholczyk, who is its director of education, offers these helpful thoughts on refusing dialysis that helpfully summarize the points we’ve made so far:

We should never choose to bring about our own or another’s death by euthanasia, suicide or other means, but we may properly recognize, on a case by case, detail-dependent basis, that at a certain point in our struggle to stay alive, procedures like dialysis may become unduly burdensome treatments that are no longer obligatory. In these cases, it’s always wise to consult clergy or other moral advisors trained in these often-difficult bioethical issues.