Saints are made not in the abstract, but in the context of the joys and struggles of their particular era, location, and circumstances. And although every century produces great saints, the twentieth century proved a particularly noteworthy time for displays of heroic holiness in the face of unprecedented wars, revolutions, atrocities, and social upheavals.

St. Pio of Pietrelcina was canonized by St. John Paul II in 2002, and his story is an inspiration to many Catholics. By the end of Pio’s earthly life in 1968, he had acquired almost mythic status. He experienced divine visions, displayed the stigmata, administered miraculous healings, was said to have a supernatural gift to read people’s hearts, and even bilocated. But he was also a man in history, and in a particularly turbulent epoch at that.

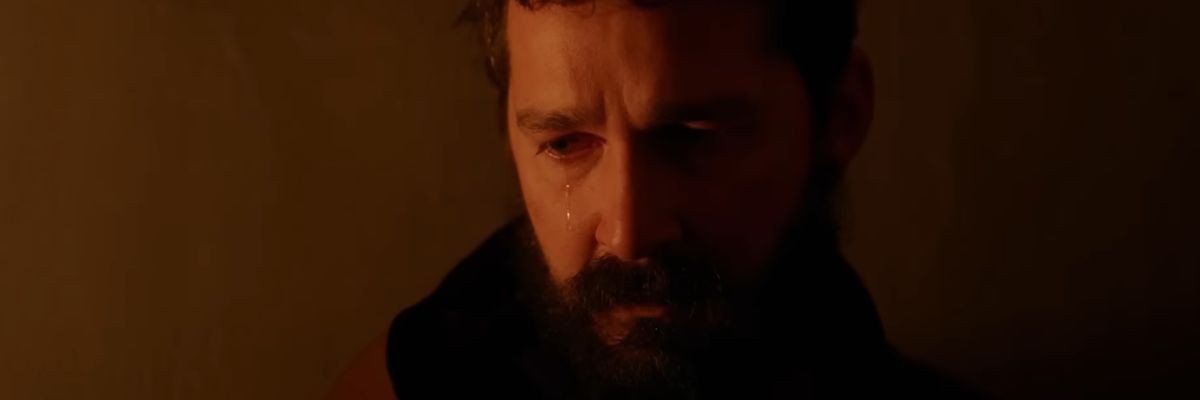

In the harrowing new film Padre Pio, directed by Abel Ferrara and co-written by Ferrara and Maurizio Braucci, we meet the young friar, played by Hollywood A-Lister Shia LaBeouf, trudging a grueling path to holiness. Despite disturbing scenes and some heavy-handed dialogue, Padre Pio may inspire some stouthearted viewers to grow in holiness amid the moral and spiritual crises of our own age.

Padre Pio is set in the southern Italian town of San Giovanni Rotondo, where Pio arrived in 1916 and remained until his death almost fifty years later. As the film begins, World War I is coming to a close, and a generation of wounded and traumatized men are returning home, only to find their town suffering and split in two by competing ideologies. In a series of borderline pornographic visions, the film shows us the society-wide struggle as mapped onto the soul of one prayerful man, Pio, portrayed with characteristic intensity by LaBeouf. He fights with Satan in his cell, alarming his fellow friars, who must forcibly restrain him. He writes to his spiritual director, Fr. Benedetto, that he wishes to take flight from his body and from this world.

At first, Pio feels alone and expresses anger at God for making him so spiritually sensitive. But his destiny is not to flee the world, even in a monastery, but rather to endure the world’s pain for the world’s benefit, growing in wisdom and charity during the short span of his life depicted in the film. We see the change of mindset begin in Pio as he counsels a penitent, “Do not let Satan take advantage of your suffering.”

Simultaneously, Satan is having his way throughout the rest of San Giovanni Rotondo. Priests stand by as a band of proto-fascisti beat up a Marxist leader. Although the film does not glorify the communists, there is certainly a tacit approval of their cause in the film’s depiction of their unjust working conditions. Pio himself quietly attends and sheds tears at the wake of a veteran who died from overwork upon his return from the front. The real Padre Pio famously had a heart for the poor, establishing a clinic in 1925 that later became a hospital. In the film, his activism is depicted not in partisanship, but by sitting with a crippled man, who miraculously stands and walks after Pio gives him his blessing.

There is one particularly harsh scene in the film that depicts Pio’s reputation as a heart-reader and confessor, but it also shows that as a young man, the future saint had a long way to go to turn his spiritual sensitivity into Christ-like compassion. A woman comes to see Pio, confessing an almost unthinkable sin, causing Pio to tell her she has a darkness in her heart. She is unhappy when he tells her sternly, “Be grateful I’m not God. I’m just a friar who prays.” Then, in a particularly emotive and memorable performance from LaBeouf, Pio drives her out of the room, repeatedly shouting at her, “Shut the f— up! Say Christ is Lord!”

As I said, disturbing.

The film reaches its climax in the town’s first free election in its history, and the results provoke a demonstration followed by a massacre. The scene cuts back and forth between the bloodshed in the streets and Pio at the altar, with a voiceover in which the friar asks for the sins of those suffering to be placed on his shoulders. In the film’s beautiful final scene, the stigmata appear in Pio’s hands while he is at prayer.

In excruciating detail, only for the strong of stomach and extremely spiritually mature, Padre Pio shows us how a saint is made. The film is rated R, featuring extreme profanity, nudity, and violence—arguably all in the service of depicting the diabolical reign against which Pio struggles. Nonetheless, the film is completely inappropriate as a resource for young people or a parish group seeking to learn more about the life of the saint.

Finally, there is the question of what to make of LaBeouf, who was widely reported by the mainstream media to have converted to Catholicism as a result of playing the part of Padre Pio. In his widely shared interview with Bishop Robert Barron, LaBeouf talked about how the Capuchin friars he lived with in California in preparation for the role helped him out of deep personal problems. He even expressed his admiration for the traditional Latin Mass, remarking that, unlike other liturgies, “It doesn’t feel like they’re trying to sell me a car.” LaBeouf’s conversion remained a point of speculation until a few days ago, when it was reported that he is in fact preparing to be confirmed in a few months.

LaBeouf’s embrace of and enthusiasm for our faith—soon, God willing, to be his faith, too—is refreshing. Indeed, let us pray that in Shia LaBeouf’s life and in the lives of those who choose to watch this gritty movie, Saint Padre Pio’s miracle-working and saint-making continue.

Padre Pio opens in theaters in the United States on June 2.