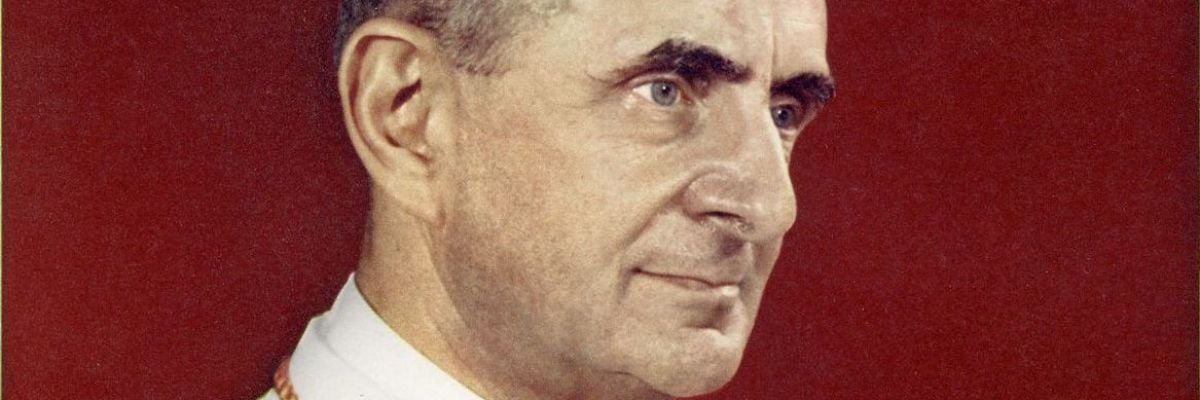

This week we commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of Humanae Vitae, the encyclical that confirmed longstanding Catholic teaching on birth control and warned prophetically of the social evils of a contraceptive culture.

Critics who reject the Catholic Church’s teaching on contraception often cite the conclusions of the 1966 Pontifical Commission on Birth Control. They say Pope Paul VI ignored the research of the very commission he set up to determine if contraception is immoral. They say members of the commission agreed almost unanimously that the Church should allow Catholics to use birth control in some cases.

This tactic is supposed to make the pope look like a stubborn traditionalist who clung to an outdated doctrine in spite of what the brightest minds in the Church had to say. However, when we examine what transpired during the years this commission met, as well as the nature of the report it released, we see that it provides no justification for dissenting against the teaching on contraception promulgated in Humanae Vitae.

For many Catholics, Pope Pius XI’s encyclical Casti Connubi had laid the issue of contraception to rest. After all, Pope Pius XII said his predecessor’s condemnation of acts done to hinder the procreation of new life within the conjugal union “is in full force today, as it was in the past and so it will be in the future.” But by the 1960s millions of American women, including many Catholics, were using the new FDA-approved birth control pill.

Origins of the commission

Some theologians said that, unlike condoms and diaphragms, the Pill did not create a physical barrier between the spouses during intercourse. Therefore, it could be a legitimate way to space children. The Pill might also be needed to stop population increases that would, according to environmentalists like Paul Ehrlich, cause hundreds of millions to die and wipe entire nations such as England out of existence. (Ehrlich’s 1968 book The Population Bomb is a classic among spectacularly wrong alarmist literature).

Pope St. John XXIII believed it would be prudent to have a response if the United Nations recommended contraception or abortion as solutions at its 1964 population conference in India. He selected six experts in sociology and medicine to discuss the issue, but he did not live to see their relatively uneventful first meeting. They reaffirmed the conclusions of Popes Pius XI and XII on contraception but said the mechanics of the birth control pill required greater study before any conclusions about it could be reached.

But some bishops in Europe were saying publicly that couples could follow their conscience regarding use of the Pill precisely because the Church had not reached a definitive conclusion about it. In response, Paul VI reconvened the Pontifical Commission for the Study of Population, Family and Births and added seven members, some of whom were notorious for their dissent against Church teaching.

When people speak about the commission, they often assume the pope simply selected the best theologians in the Church, and so he should have followed whatever they recommended. But there is evidence the pope wanted a commission that would give him arguments to test rather than advice to follow. The late moral theologian Germain Grisez, who worked behind the scenes to help future commission member Fr. John Ford defend Church teaching, told the Catholic News Agency:

[Pope Paul VI] was perfectly happy to have a lot of people on the commission who thought that change was possible. He wanted to see what kind of case they could make for that view. He was not at all imagining that he could delegate to a committee the power to decide what the Church’s teaching is going to be.

Robert McClory confirms this in his book Turning Point, which chronicles the history of the commission from the perspective of an American married couple who were invited to join its later sessions. According to McClory (who supports changing Church teaching on contraception), the invitation to the progressive theologian Bernard Häring said, “It is the High Authority who has wanted diverse currents of opinion to be represented in the group. Yours are well known” (Turning Point, 48).

One example of Häring’s “diversity” was his claim that procreation could not be an essential end of sex because it was physiologically impossible for many acts of intercourse to result in pregnancy (such as when a woman has not ovulated). But this is like saying that learning is not an essential end of reading because it is physiologically impossible to retain everything we’ve read.

Despite challenges from revisionist theologians like Häring, the second and third meetings of the commission also ended without a consensus. But as media inquiries continued about a commission that was supposed to operate discreetly, Paul VI decided to increase the membership threefold and bring in voices that were not normally heard at Vatican gatherings but were necessary for the subject of conjugal relations: married men and women.

The laity joins the discussion

Patrick and Patty Crowley, the Catholic founders of the Christian Family Movement, conducted a survey of American Catholic attitudes toward contraception and the rhythm method of birth control. By the time they arrived for the final commission meeting in June 1966, the commission had swelled to seventy-two members, though some were unable to attend. The most notable absent figure was the future Pope John Paul II, Karol Wojtyla, who remained in occupied Poland due to the Soviet Union’s travel restrictions.

The last commission meeting, which took place over three months, was by far the most contentious. German physician Albert Gorres claimed the Church had a “celibate psychosis” that it was inflicting on the laity. The Crowleys said their surveys showed that the rhythm method “did nothing to foster marital love” and provided no greater unity between the spouses. Colett Povin, another married woman invited to the commission, slammed temperature-based rhythm methods: “When you die, God is going to say, ‘Did you love?’ He isn’t going to say, ‘Did you take your temperature?’” (Turning Point, 105).

A few members of the commission tried to steer the discussion away from the consequences of forbidding contraception and remind everyone about the far more serious consequences of allowing contraception. But when Jesuit priest Fr. Marcelino Zalba asked about “the millions we have sent to hell if these norms [in favor of contraception] were not valid,” he was met with this flippant response from Patty Crowley: “Fr. Zalba, do you really believe that God has carried out all your orders?” (Turning Point, 122).

By this point, the commission had moved far away from its original focus on the mechanics of the birth control pill. A majority of theologians, many of whom were moved by the stories of Catholics who felt the prohibition on contraception harmed their marriages, claimed that contraception was not intrinsically evil, and they drafted an eleven-page report summarizing their position. Meanwhile, Fr. John Ford, along with a handful of other commission members who rejected the proposal, drafted their own 9,000-word defense of the Church’s teaching (this would later be called the “minority report,” even though it was not an official document).

The commission’s main report (now called the “majority report”) and Fr. Ford’s rebuttal were given to Pope Paul VI on June 28, 1966. Four months later, the pope commented on the majority report saying it carried “grave implications . . . which demanded logical considerations.” Fearing that this tepid response meant the report would be rejected, some members worried the entire report would be buried, and so they leaked it to the National Catholic Reporter, a paper known then, as now, for promoting dissenting opinions against Church teaching.

Robert Kaiser, a journalist who reported extensively on the commission at the time, said that because of the leak “people would have proof positive that authorities in the Church were not only divided but also leaning preponderantly to a new view of marriage and the family that did not condemn couples to hell for loving each other, no matter what the calendar said” (The Encyclical That Never Was, 233).

You’ll often find, despite the public leak of this document, that people who cite it against Humanae Vitae usually haven’t read it. They just make a bald appeal to authority and ask: “Why wouldn’t you agree with the commission the pope set up to investigate birth control?”

This makes me want to say in response, “Why wouldn’t you agree with the pope, the successor of St. Peter who acted in communion with the teaching of the entire Catholic Church for the last 2,000 years when he condemned birth control?”

In response, dissenters usually claim that the pope was clinging to an inherited, biased tradition against contraception. They say the commission showed how new, modern understandings of marriage and sex support changing Church teaching. But does the commission’s report include irrefutable arguments or evidence that overturns what the Church has always taught about the need to not eliminate the procreative end of the conjugal act?

Not by a long shot.

Examining the report

Despite the novelty of the birth control pill at the time, contraceptive methods have been used for thousands of years, yet the commission never cites what previous Church fathers, saints, popes, or councils have said on the matter. Instead, it merely claims “the traditional doctrine of the Church” condemned “a truly ‘contraceptive’ mentality and

practice” rather than every single act of contraception. This reading of Church history comes from John T. Noonan’s contribution to the commission wherein he presented a summary of his book Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists, which was published subsequently in 1965.

Other people claim the Church Fathers mistakenly viewed sex as being permissible only if done in order to procreate. But Noonan admits that the Church never condemned sex between elderly couples who are past childbearing years. And even though he voted with the commission to change Church teaching, He writes:

The teachers of the Church have taught without hesitation or variation that certain acts preventing procreation are gravely sinful. No Catholic theologian has ever taught, “Contraception is a good act.” The teaching on contraception is clear and apparently fixed forever (Contraception, 6).

The commission also claimed that “developments” in the Church’s teaching on sex (such as the primacy of expressing love) and social developments such as lower infant mortality rates make contraception acceptable even though it was condemned in the past. Testimonies such as those compiled by the Crowleys also made an indirect appearance in this statement from the majority report: “Then must be considered the sense of the faithful: according to it, condemnation of a couple to a long and often heroic abstinence as the means to regulate conception, cannot be founded on the truth.”

But these arguments fail, because the intrinsic morality of an act is not dependent on demographic facts or societal opinions. For example, the commission steadfastly rejected abortion as a way to space children, but modern dissidents say the Church should also change its teaching on that issue, because women’s place in society has changed and many Catholics identify as pro-choice and find it impossible to follow a complete ban on abortion.

Finally, the report gives what will become a standard interpretation among dissenters of Church teaching on the issue of contraception:

It is not to contradict the genuine sense of this tradition and the purpose of the previous doctrinal condemnations if we speak of the regulation of conception by using means, human and decent, ordered to favoring fecundity in the totality of married life and toward the realization of the authentic values of a fruitful matrimonial community.

In other words, couples don’t have to abstain from contraception because it is intrinsically evil. They just have to make sure their use of contraception does not affect “the fecundity in the totality of married life.”

But what does that mean? Do couples have to make sure only that they use contraception for nearly all but not every sexual act? Do they just have to allow 51 percent of conjugal acts to have the possibility of conception? Or would simply having the standard 2.1 children suffice?

Dissenters claim that sexual morality in marriage comes not from the morality of each isolated sexual act but the morality and focus of the marriage as a whole. But does this reasoning make sense?

Imagine if someone claimed that occasional instances of adultery weren’t wrong as long as they were being used as a means to strengthen the overall unity of the marriage (e.g., a husband wanting to boost his confidence so he can better love his wife)? Should we demand that every single sexual act be faithful or promote “the faithfulness in the totality of married life”?

If that reasoning doesn’t justify occasional acts of adultery, then it doesn’t justify occasional acts of contraception (though I hope dissenters won’t bite the bullet and just add the intrinsic sinfulness of adultery to the list of teachings they want to change). Philosopher Ralph McInerny also offers this helpful response:

The principle of totality cannot ground the claim that singular acts which, taken as such are offensive, cease to be so when considered in the light of the moral life taken as a whole. The moral imperative is not that we should act well more often than not. Rather it is: do good and avoid evil (Why Humanae Vitae Was Right, 341).

It can be distressing to find that a group of high-ranking cardinals, bishops, and theologians gathered together to discuss moral theology, and the truth did not win out in the discussion. However, Christ never promised that every single Catholic—or even every single member of the clergy—would be preserved from error. Even the pope can make mistakes when he is not speaking ex cathedra, or when he is not formally defining a dogma.

What Christ did promise was that the gates of hell would not prevail against the Church (Matt. 16:18). That means the entire college of bishops and the pope, speaking in his capacity as the successor of St. Peter, will never formally bind the Church to a theological or moral error. The Holy Spirit will protect the Church, even when it seems like many of its members have lost their way.

In the fourth century, the Arian heresy found favor with Emperor Constantius, and it overran the eastern part of the Empire. Fortunately, one bishop of the East, St. Athanasius, had the courage to stand against it, no matter what his contemporaries thought and no matter how often the emperor exiled him. On the saint’s tombstone is the inscription Athanasius contra mundum (“Athanasius against the world”).

The same grace of the Holy Spirit can be seen in the wisdom of Paul VI, who stood against the world, and even high-ranking members of the Church, in order to uphold the truth that every single instance of the marital act must be ordered toward the unity of the couple and the procreative potential of God to bless the couple with the gift of a child as an enduring sign of their matrimonial love.

Sidebar: Pope Paul VI’s Response to the Report

Humanae Vitae includes responses to those who would object to the Church’s teachings on contraception, including responses to some of the arguments made in the commission’s final report. In the section on “Unlawful Birth Control Methods,” the pope addresses those who would defend the use of contraception for the end of promoting the overall good of the marriage:

Though it is true that sometimes it is lawful to tolerate a lesser moral evil in order to avoid a greater evil or in order to promote a greater good, it is never lawful, even for the gravest reasons, to do evil that good may come of it—in other words, to intend directly something which of its very nature contradicts the moral order and which must therefore be judged unworthy of man, even though the intention is to protect or promote the welfare of an individual, of a family, or of society in general. Consequently, it is a serious error to think that a whole married life of otherwise normal relations can justify sexual intercourse which is deliberately contraceptive and so intrinsically wrong (14).

For more on the many dimensions of wisdom found in Humanae Vitae, check out the new book Inseparable from Catholic Answers Press, available now at a special introductory price.