Nearly a quarter century after Pope Leo X condemned the teachings of the revolutionary Augustinian monk Martin Luther and after years of political and religious turmoil, Alessandro Farnese was elected to the papacy, taking the name Paul III (r. 1534–1549).

The Protestant Revolution was in full force and a universal response was required. Pope Paul recognized the need for reform in the Church and laid the foundation for what became known as the Catholic Reformation (sometimes, inappropriately, referred to as the “Counter-Reformation”).

He saw the program in three stages; reform of the papal curia, calling an ecumenical council, and implementation of reforms by the papacy. Paul focused his energies on calling an ecumenical council, which would consume most of his pontificate. Scheduling the great event and completing its work in such historically turbulent times would prove difficult, to say the least.

Paul III called for the council to be held in the northern Italian city of Mantua but his plan was thrown into chaos when war erupted between France and the Holy Roman Empire in the summer of 1536 over control of Milan. Additionally, the Duke of Mantua told the pope he could not guarantee the safety of the assembled bishops without thousands of troops stationed at papal expense.

Concerned the presence of armed soldiers in the city would lead to charges of coercion, Paul decided to postpone the council until he could find another location. Vicenza agreed to host the council in May 1538 and Paul called bishops to the city. When few bishops arrived, the pope, once more, postponed the council. Three years later, Pope Paul III and Emperor Charles V met in Italy to discuss the council, and the emperor suggested the imperial city of Trent as the location for the council. The pope agreed and issued a bull calling for the council to meet at Trent in November 1542. However, continued warfare in Europe prevented the arrival of a sufficient number of bishops and the council was once again suspended. Eventually, peace was achieved and the council commenced on December 13, 1545.

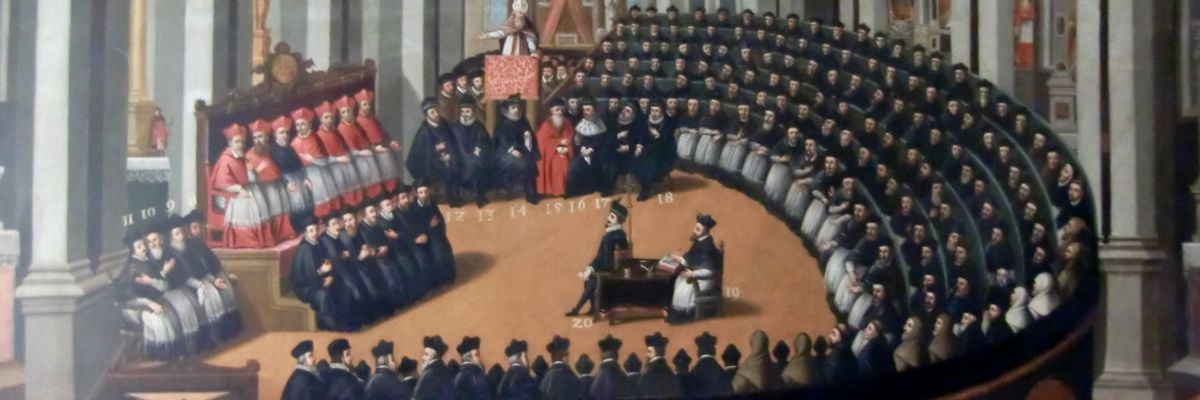

The Council of Trent is one of the most important meetings in Church history. Called to define authentic Catholic doctrine in response to the Protestant revolution and usher in a period of authentic reform, the council’s sessions would span eighteen years (due to two lengthy suspensions). But the actual work of the council took four and a half years, encompassing three pontificates. The council produced more decrees and canons by volume than the entire legislation from the previous eighteen councils.

The first meeting occurred from 1545–1547 and principally focused on establishing the procedures to utilize for conducting conciliar business. It also passed decrees concerning Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition, the canon of Scripture (the seventy-three books contained in the Vulgate), Original Sin, and Justification. The bishops rejected the key Protestant doctrine of “faith alone” justification, declaring that faith must be accompanied by hope and love, and illustrated in life through good works. The council also began a doctrinal review of the Sacraments and defined Baptism and Confirmation. Reform decrees outlawed absenteeism (bishops not living in their diocese) and pluralism (one man as bishop of multiple dioceses). Unfortunately, the great work begun by the council was suspended when a papal army marching through Trent brought typhus, leaving several bishops ill and even killing one. The council fathers voted to move the meeting to Bologna and reconvene in forty days, but the proposed change in location so angered Charles V that Paul III suspended the council for another four years.

When the council convened again, Pope Julius III (r. 1550–1555), who had been the senior papal legate at the first meeting of Trent, succeeded Paul III. At this second meeting, the bishops affirmed Catholic teaching on the Eucharist, specifically the doctrine of transubstantiation, as well as the sacraments of penance and extreme unction (anointing of the sick). Another conciliar suspension occurred in 1552 when a Protestant army conquered Innsbruck, only 110 miles from Trent, and Pope Julius feared an attack on the assembled bishops. An entire decade would pass before the council’s work resumed.

In the intervening decade, Pope Julius III died and was succeeded by Giovanni Angelo Medici, who took the name Pius IV (r. 1559–1565). Committed to reform, Pius IV called the world’s bishops to assemble once more in Trent for the third meeting of the council. This meeting was the most productive and well attended, with over 250 bishops. The conciliar fathers passed decrees concerning the hierarchical structure of the Church, the religious life, Purgatory, the veneration of relics, the intercession of the saints, and indulgences. The council also focused on the training and formation of clergy by mandating the establishment of a “seminary” in each diocese throughout the Church. The abuse of spiritual penalties, such as excommunication and interdict, for political purposes was addressed as bishops were reminded to use these penalties sparingly and for the proper purpose.

The council required bishops to live in their diocese and not be absent for more than three months and never during the seasons of Advent and Lent. Bishops were exhorted to visit all parishes in the diocese at least once a year, and to preach every Sunday. The unique ministry of the Roman Pontiff was highlighted in response to Protestant attacks against the papacy. In order to reinvigorate Catholic spirituality, the council fathers requested the revision and publication of the Roman Missal and the Breviary (Divine Office). The council fathers also demanded the creation of a universal Catechism that could be used to teach the Faith in order to combat the errors of Protestantism.

After three meetings over an eighteen-year period, Pope Pius IV closed the council on December 4, 1563 and promulgated its decrees. The Council of Trent fundamentally changed the Catholic Church, which became more vibrant, dedicated, and focused on evangelization. In the words of French historian Henri Daniel-Rops, “There was indeed, in 1563, a new Catholic Church, more sure of her dogma, more worthy to govern souls, more conscious of her function and her duties.”