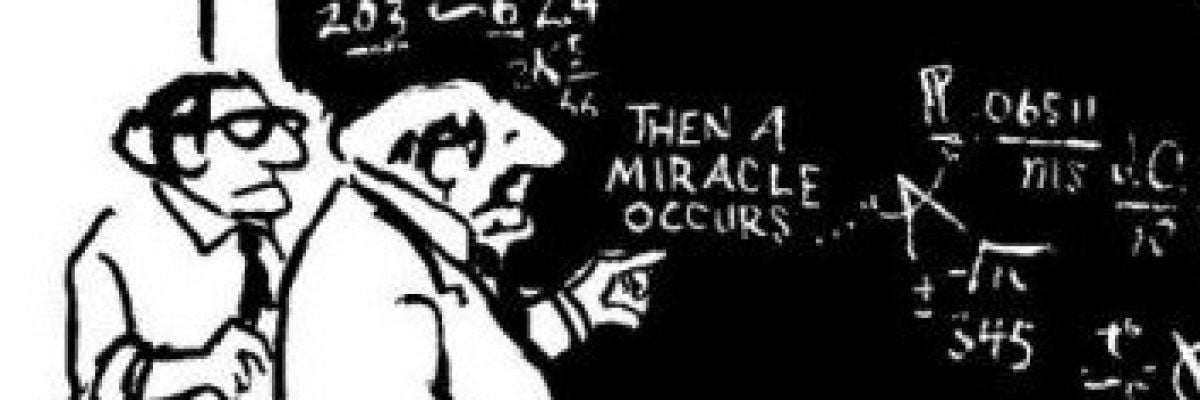

Many atheists say that all arguments for the existence of God are just fallacious “God-of-the-gaps” reasoning. They claim that any evidence offered for the existence of God, such as the beginning, contingency, and fine-tuning of the universe, are nothing more than appeals to ignorance. These arguments are supposedly on par with primitive explanations of natural events (such as lightning) that erroneously included God as a direct cause. Modern arguments for theism are likewise lampooned as primitive “God did it” explanations that will be usurped by modern science.

The problem with the “God-of-the-gaps” objection is that it can have unintended consequences for atheism. Specifically, it makes atheism impossible to falsify, in the same way that most religious beliefs cannot be falsified. Rather than rely on science, “God-of-the-gaps” pushes atheism far away from being a scientific belief.

Why is that the case?

A claim is falsifiable if evidence can be presented that can disprove it (Karl Popper argued that this was a necessary condition for a claim to be scientific). For example, evolutionary theory could be falsified by the discovery of modern animals that were fossilized in ancient rock layers, or what J.B.S. Haldane called “a Precambrian rabbit.” Likewise, the discovery of manuscript P52 of the Gospel of John, which is dated to the early second century, falsified the theory that the Gospel of John was not written until the year 150 A.D. or even later.

So, can atheism be falsified? An atheist might say, “Of course atheism can be falsified—just prove that God exists!”

But how exactly is the theist supposed to do this? Usually atheists demand some kind of over-the-top display of power to confirm God’s existence. The late N.R. Hanson gave one such piece of evidence that would convince him:

Suppose . . . that on next Tuesday morning, just after breakfast, all of us in this one world are knocked to our knees by a percussive and ear-shattering thunderclap . . . the heavens open – the clouds pull apart – revealing an unbelievably immense and Zeus-like figure, towering above us like a hundred Everests. He frowns darkly as lightning plays across the features of his Michaelangeloid face. He then points down – at me! – and exclaims, for every man, woman and child to hear “I have had quite enough of your too-clever logic-chopping and word-watching in matters of theology. Be assured, N.R. Hanson, that I do most certainly exist (N.R. Hanson. What I Do Not Believe and Other Essays. Springer, 1971).

If God did this, then surely we would know he existed, right? Well, why wouldn’t this kind of evidence also be subject to the “God-of-the-gaps” objection? Just because we don’t know how a giant man can appear in the sky doesn’t mean there is no natural explanation for him. Maybe aliens or time-travelers are at work, deceiving us?

Even “low-key” evidence is vulnerable to the “God-of-the-gaps” objection. Some atheists say that if Christian preachers could heal amputated limbs, that would convince them God existed. But once again, aren’t we just taking a gap in our knowledge (“I don’t know how these limbs are being healed”) and filling it with, “Therefore, God did it?”

Atheists have two options. First, they could admit that no amount of evidence could satisfy the “God-of-the gaps-objection” and show God exists. This would leave atheism behind the safe veil of protection that cloaks other unfalsifiable beliefs, such as the belief the entire world is a computer simulation.

If atheists say that atheism does not claim “There is no God,” only that some people lack a belief in God, then atheism can’t be true at all. A belief can only be true (in a non-trivial sense) when it makes a claim about the world and not just about someone’s state of mind. Saying “I lack a belief in God” no more informs us about reality than saying “I lack a belief in aliens” informs us about the facts related to extraterrestrial life.

If these options proved unsatisfactory, atheists could instead put forward strict standards of what kind of evidence would falsify atheism and prove God exists. Although, if those standards included extremely improbable events or something coming from nothing (such as perfect prophecy or healing an amputee) then the traditional arguments for God come back into play, since they include similar phenomena about the universe (such as cosmic fine-tuning and the origin of the universe in the finite past) in order to show God exists.

Rather than argue from what we don’t know (or “God-of-the-gaps”), good arguments for theism take what we do know and show how it logically leads to the transcendent creator of the universe.