Perhaps you’ve noticed one of the many stories about the Dead Sea Scrolls that have appeared recently (like this one), trumpeting the decoding of one of the two remaining undeciphered Dead Sea Scrolls.

As it turns out, this scroll sheds light on the calendar employed by the Jewish sect (likely the Essenes—more on them below) that authored the scrolls, a calendar that differed markedly from the lunar version used by the ruling temple establishment in Jerusalem. The scroll calendar was a unique 364-day calendar, which could easily be divided into four and seven, guaranteeing that feast days would always fall on exactly the same day each year!

According to Eshbal Ratson and Jonathan Ben-Dov of the University of Haifa, who deciphered the scroll, this calendar is “perfect” because it eliminated a major problem of lunar calendars: what happens if a major feast happens to fall on a Sabbath? Also, as the professors note, the “calendar is unchanging, and it appears to have embodied the beliefs of the members of this community regarding perfection and holiness.”

This discovery is a good occasion for us to go over what the Dead Sea Scrolls—and the community which composed them—are all about, and what importance they may have for helping us understand Jesus.

When were the scrolls discovered?

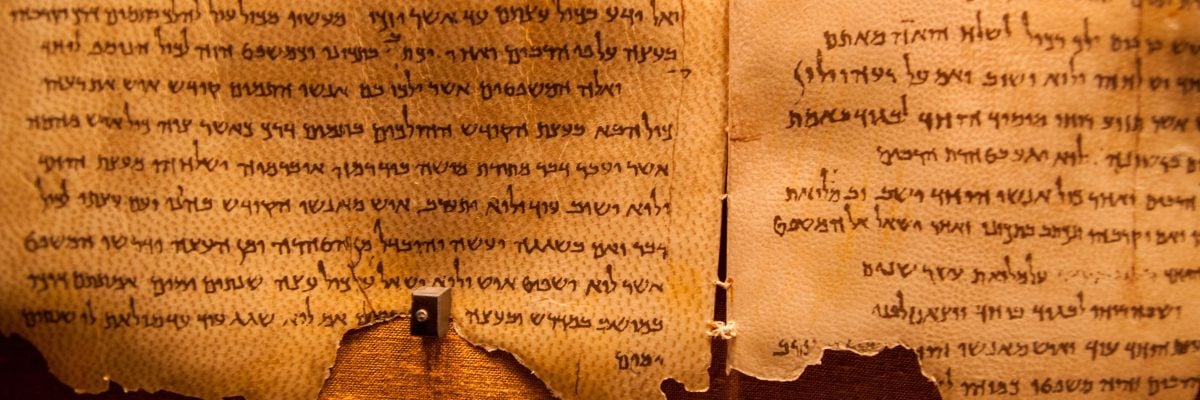

Sometime in either late 1946 or early 1947, a Bedouin shepherd accidentally discovered a cave containing ancient manuscripts in the desert region near the shores of the Dead Sea. What was in that cave turned out to be the beginnings of the greatest archaeological discovery of the twentieth century. In total, eleven caves were found in the region (with a twelfth and possibly a thirteenth discovered in 2017), containing copies of many biblical books, along with other religious writings and communal documents belonging to the Jewish sect that compiled them. In all likelihood, this group was the Essenes.

The New Testament reveals that there were numerous sects within the Judaism of Jesus’ day—the Pharisees and the Sadducees, who ruled the temple priesthood, immediately spring to mind, of course. But don’t forget groups like the Herodians, and even the warmongering Zealots (a group from which Jesus called an apostle, Simon). Another active group in the first century, although one not specifically mentioned in the New Testament, was the aforementioned Essenes.

The Essenes believed that the temple establishment in Jerusalem had become hopelessly corrupt, and that their community alone possessed the true faith in all its purity. Withdrawing to the desert from what they viewed as a hopelessly corrupt society, they prepared for an imminent end-times battle between the “Sons of Light” (themselves) and the “Sons of Darkness” (essentially, everybody else). They settled in the harsh climes of the Dead Sea region, where the caves that housed the scrolls were eventually discovered.

What can the scrolls tell us about Jesus?

Let’s clear up a major misconception people have about the Dead Sea Scrolls: they are not Christian documents, although their composition overlaps with the life and times of Jesus and the early Church (they were generally composed between the third century B.C. and first century A.D.). However, they do show us what many Jews who were roughly contemporaneous with Jesus believed about the coming messianic age. These beliefs were expectations that were common to many Jews of Jesus’ day. When we read the scrolls through this lens, we see many points of contact between what the authors of the scrolls expected of the Messiah and Jesus’ own words and deeds.

One example comes from an Aramaic scroll found in Cave 4 (which was the motherlode, the cave containing the most scrolls), which speaks of a coming “Son of God,” a “Son of the Most High” who will be “great” and reign forever. Notice how this closely echoes the Annunciation narrative found in Luke 1. Another scroll, known as the “Melchizedek Scroll,” found in Cave 11, speaks of the appearance of one who seems to be God, having the power to forgive and defeat Satan.

A “Get Out of Jail Free” card?

In some cases, the scrolls can give us unique windows of insight into some hard-to-understand New Testament passages. For example, the scroll known as 4Q521 (signifying that it was found in cave 4 at Qumran — the region where the scrolls were discovered — document or fragment 521”) shows that Jesus did in fact proclaim himself as Messiah, despite claims to the contrary by many moderns. Moreover, it shows that Jesus did so in a very culturally relevant manner for his time.

Jesus’ reply to the imprisoned John the Baptist (Matt 11:2–6; Luke 7:18–23) is seen by some as not messianic. When asked, “Are you he who is to come, or shall we look for another?” (Matt 11:3), Jesus answers in what appears to some as a vague manner, using words from Isaiah 61:

“Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up, and the poor have good news preached to them. And blessed is he who takes no offense at me” (Matt 11:46).

4Q521 says this:

For the heavens and the earth will listen to his Messiah…For he will honor the devout upon the throne of eternal royalty, freeing prisoners, giving sight to the blind, straightening out the twisted…and the Lord will perform marvelous acts…for he will heal the badly wounded and will make the dead live, he will proclaim good news to the meek, give lavishly to the needy, lead the exiled, and enrich the hungry.

Comparing these two texts, you can easily see by why John asked the question about Jesus’ messiahship, and why Jesus replied the way he did. It was assumed that when the Messiah arrived, according to 4Q521, “prisoners would be set free.” The righteous John, at this time languishing in Herod’s fortress at Machaerus, is wondering why Jesus hasn’t sprung him from prison. Jesus replies to John by noting that his marvelous works indeed match up with the deeds of the expected Messiah, in line with the teaching of Isaiah 61 and 4Q521.

For Jesus to be any more explicit than this would arouse the attention of the secular authorities, prior to the completion of his messianic mission. However, attentive Jews would have understood Jesus’ claims. In a culturally relevant way, Jesus is inviting his fellow Hebrews to consider the evidence of his ministry and draw their own conclusions.

There are many reasons why the Dead Sea Scrolls are important. As we have seen, one reason is that they offer us helpful context for Jesus’ ministry. Last year, two more caves were discovered, which may have housed even more scrolls. Having worked on an excavation in Jerusalem myself, I’m thrilled whenever I hear about such new discoveries. Archaeology continues to turn up more and more of the material remains of Jesus’ day—and this can only help us to understand his life and teachings in ever deeper ways.