Duke William of Aquitaine founded the monastery of Cluny in the early tenth century to assuage a guilty conscience for a violent sin in his youth. He could not have known that his gift would result in one of the most famous speeches in history.

Cluny contributed to an ecclesial reform movement in the eleventh century by producing several monks who were elected to the papacy. One such monk was Odo of Lagery, who became pope on March 12, 1088, taking the name Urban II.

Like the earlier reforming pope St. Leo IX (r. 1049-1054), Urban decided to exercise papal authority and power at the service of the reform movement by travelling throughout Christendom. His visit to France was the first by a pope in a generation and was intended to consecrate the great abbey church at Cluny. The pope took advantage of this road trip to implement the reform movement by meeting with bishops and attending local councils. Urban’s fourteen-month trip through France saw him visit the regions of Provence, Languedoc, the Rhône valley, Burgundy, Anjou, and the cities of Avignon, Lyons, Le Mans, Tours, Poitiers, Bordeaux, Carcassonne, Toulouse, Montpellier, and Arles. He arrived at Clermont, which is southwest of Cluny, in late November 1095 to attend a local council.

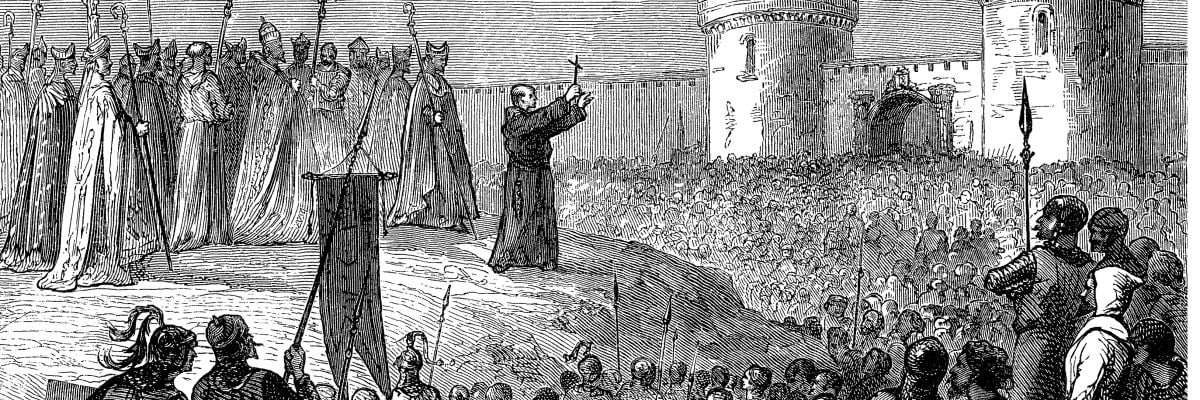

The agenda at Clermont centered on the issues of reform. Discipline canons providing penalties for violations of Church laws regarding simony, celibacy, and lay investiture were passed. The main event of the council occurred on November 27, when Urban spoke to a large assembly in the open air. This speech inaugurated the Crusades movement and is one of the most significant papal utterances in the 2,000-year history of the Church. Despite the significance of the event, there are no direct records of what Urban actually said; but there are five accounts of the speech all written after the event by authors (Fulcher of Chartres, Robert the Monk, Baldric of Dol, Guibert of Nogent, and William of Malmesbury) who were either present at the council or who compiled their version of the speech from those who were present.

These accounts illustrate three themes in Urban’s speech: the need for the liberation of the Holy City of Jerusalem; the violent activities of the Turks; and an exhortation to Christian warriors to take up arms. Urban focused his speech on the Cross and urged the warriors of France to embrace an armed penitential pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The liberation of Jerusalem was paramount for Urban and he knew this cause would resonate with the assembled French nobility and knights.

The French had a great devotion to the Holy City and pilgrimages were extremely popular. Jerusalem was considered the center of the world and its occupation by the Muslims was distasteful to the citizens of Christendom. Urban highlighted the importance of Jerusalem in the life of Christ saying, “This [city] the Redeemer of the human race had made illustrious by His advent, has beautified by residence, has consecrated by suffering, has redeemed by death, has glorified by burial.” He pleaded with the French warriors to forego their selfish desires and goals and come to the aid of Jerusalem: “This royal city . . . is now held captive by His enemies, and is in subjection to those who do not know God. . . . She seeks therefore and desires to be liberated and does not cease to implore you to come to her aid.”

Urban’s preaching focused also on the plight of Christians in the Holy Land, who were subjected to cruel tortures and punishments at the hands of the Turks. His graphic description of Turkish atrocities was designed to elicit a visceral response from his hearers so that they would volunteer to liberate their Christian brothers and sisters. Urban reported the various ways the Turks tortured and killed Christians:

They perforate their navels, and dragging forth the extremity of the intestines, bind it to a stake; then with flogging they lead the victim around until the viscera having gushed forth the victim falls prostrate upon the ground. Others they bind to a post and pierce with arrows. Others they compel to extend their necks and then, attacking them with naked swords attempt to cut through the neck with a single blow.

After mentioning the violation of women, the pope exhorted the assembled warriors at Clermont to rush to the defense of their persecuted brethren saying, “On whom therefore is the labor of avenging these wrongs and of recovering this territory incumbent, if not upon you?”

Many would respond to the need to liberate Jerusalem due to the immense devotion in France for the Holy City, and some would rage at the injustices foisted upon fellow Christians in the east. Still, Urban feared that many warriors would hesitate to sign up for the herculean task.

Due to his noble background, Urban was intimately familiar with the mentality of warriors and knew how to motivate knights. In his speech at Clermont, Urban appealed to the military adventures of the great warriors in French history in order to exhort his listeners to join the Crusade: “Let the deeds of your ancestors move you and incite your minds to manly achievements. Oh, most valiant soldiers and descendants of invincible ancestors, be not degenerate, but recall the valor of your progenitors.”

Finally, Urban offered a spiritual incentive for warriors to participate in the Crusade – a plenary indulgence. Through the power and authority of the Petrine Office, Urban decreed that “Whoever goes on the journey to free the church of God in Jerusalem out of devotion alone, and not for the gaining of glory or money, can substitute the journey for all penance for sin.”

Pope Urban II’s speech at Clermont was one of the most important in Western history. It launched the First Crusade, which resulted in the liberation of Jerusalem from Muslim control in 1099 and it began the Crusading movement, which lasted for nearly seven hundred years and formed an integral part of Christian life, culture, and spirituality.