Catholics often appeal to yesterday’s reading from John 19 for biblical support of the perpetual virginity of Mary.

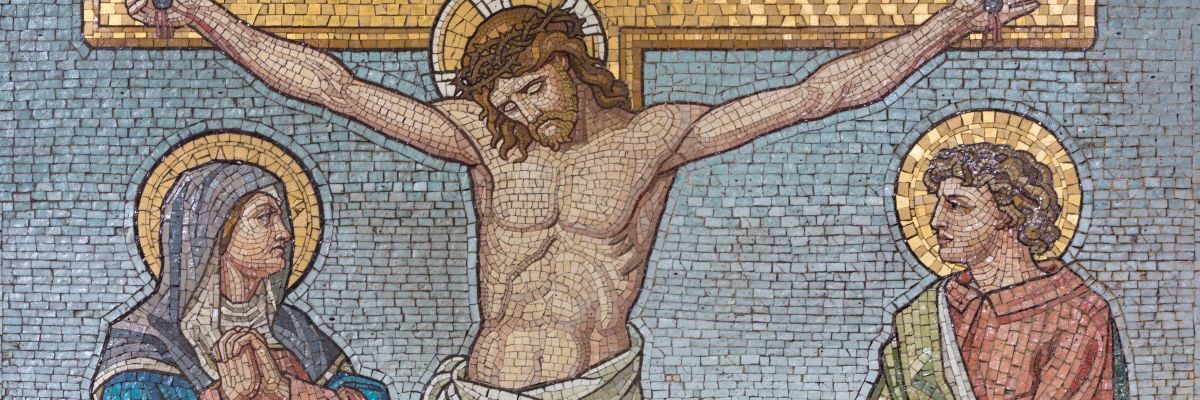

When Jesus saw his mother, and the disciple whom he loved standing near, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son!” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother!” And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home. (John 19:26-27)

If the “brothers of the Lord” (Matt. 13:55) were Mary’s biological children, so the Catholic argument goes, Jesus wouldn’t have entrusted Mary into John’s care. The duty to care for Mary would have belonged to Jesus’ brothers. But since Jesus entrusts Mary into John’s care, it follows that Jesus’ “brothers” were not Mary’s biological children.

There are two ways that Protestant apologists counter this argument.

One is that Jesus didn’t entrust Mary into the care of his brothers because they were unbelievers at the time of the crucifixion, and wouldn’t become believers until after the resurrection. A supporting text for this is John 7:5, where John tells us, “his brethren did not believe in him.” It’s argued that John as a believer would have been closer to Mary than Jesus’ unbelieving brothers.

Our first response is that this counter assumes Jesus’ brothers weren’t believers at the time of the crucifixion. But that’s not entirely clear.

John 7:5 tells us that Jesus’ brothers didn’t believe in him at the time of the Feast of Tabernacles, which was quite a bit prior to the crucifixion. And there’s nothing in the New Testament that tells us they became believers after the resurrection. The New Testament portrays them as believers after the resurrection, but that doesn’t mean that’s the time when they became believers.

In fact, we don’t know for sure when they became believers. There’s nothing in the New Testament that definitively tells us one-way or the other. Therefore, it makes no sense to simply assert that none of his family members were believers at the time of the crucifixion. “What you can’t show, you don’t know.”

This appeal to ignorance, however, is based on the supposition that the “brothers of the Lord” were not numbered among the twelve. If we suppose that James and Jude, two of the four “brothers of the Lord” (Matt. 13:55), are identical to Jude listed as an apostle (Luke 6:16) and the apostle James the son of Alpheus (James son of Zebedee is martyred in Acts 12:2), then we have good reason to think they were believers at the time of the Crucifixion.

On the night of the Last Supper, Jesus prays to the Father: “While I was with them [the apostles], I kept them in thy name, which thou hast given me; I have guarded them, and none of them is lost but the son of perdition” (John 17:12). James and Jude, who are present at the Last Supper, can’t be unbelievers and at the same time said to be kept in the Father’s name and guarded by Jesus.

So, presuming that the brothers of the Lord were numbered among the twelve, we have good reason to think they were believers at the time of the crucifixion. And if so, Jesus would have entrusted Mary into their care if they were her biological children—that is, if we grant the premise that Jesus preferred to entrust Mary only into the care of a believer.

This leads us to a second problem with this Protestant counter: the premise that emotional closeness to Mary as a believer supersedes natural rights and obligations is sheer speculation.

But there is no reason to think this—the duty to care for an aging parent is a duty of the natural order, not the order of emotions. Moreover, there’s evidence that in Jesus’ mind emotional closeness would not supersede the natural duty of his brothers to care for their mother—that is, on supposition his “brothers” are actually Mary’s biological children.

Recall what Jesus says in Mark 7:8-13 about the Pharisee’s Corban tradition (which held that if someone gives an offering to the Temple of the money saved to care for their elderly parents, they would be excused from their obligation to care for them): they “leave the commandment of God [the fourth commandment]” and “make void the word of God.”

So not only is it unsupported speculation to argue that, for Jesus, emotional closeness to Mary would outweigh the natural duties of children to their parents, there’s evidence to the contrary.

Another problem with this counter is that it fails to consider Jesus’ omniscience as the Second Person of the Trinity. Even if we grant that his brothers didn’t believe in him at the time of the crucifixion, Jesus knew they would eventually come to believe in him within a matter of days. We’re told in 1 Corinthians 15:7 that Jesus appeared to James, the chief of the brothers.

Given this knowledge, Jesus’ entrustment of Mary to John would have only been a temporary state of affairs, a state of affairs that would be fixed very shortly thereafter when James came to believe.

But John 19:27 implies that Mary remained with John for an extended period of time, seemingly permanently: “And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home.” There’s nothing in the text to indicate that Mary was to stay with John just for a few days.

Since this counter doesn’t succeed in accounting for Jesus’ entrustment of Mary to John, the best explanation remains that the brethren were not children of Mary’s own womb.

A second counter that some Protestants make to a Catholic’s appeal to John 19:26-27 is that Jesus’ brothers weren’t present at the foot of the cross for Jesus to entrust Mary into their care.

There are two things we can say in response. First, it may be that the brothers were present there on Golgotha. The idea that only women were there, with John being the exception, is false. Luke tells us that all who knew Jesus were present: “And all his acquaintances [pantes hoi gnōstoi autō] and the women who had followed him from Galilee stood at a distance and saw these things” (Luke 23:49). We can assume his acquaintances would include his family members, especially since at least one family member was there—his mother Mary.

Second, Jesus didn’t need to make arrangements for Mary’s care from the cross if she had other children; it would have been assumed they would care for her, even if they weren’t present at the crucifixion. Moreover, making other arrangements would have been horribly insulting to her other children. And that goes against Jesus’ strong view on God’s law that children must care for their aging parents, as we saw above in Mark 7:8-13.

In the end, Mary not having other children remains the best explanation of Jesus’ entrustment of Mary to John’s care. John 19:26-27, therefore, remains a strong support of the Catholic claim to biblical evidence for Mary’s perpetual virginity.