There’s a popular image that makes its rounds on social media every year, claiming that the Christian celebration of Easter finds its roots in the more ancient celebration of the Germanic goddess Eostre, also known as Ishtar. The text in the graphic reads as follows:

This is Ishtar:

Pronounced “Easter.”

Easter was originally the celebration of Ishtar, the Assyrian and Babylonian goddess of fertility and sex. Her symbols (like the egg and the bunny) were and still are fertility and sex symbols (or did you actually think eggs and bunnies had anything to do with the resurrection?). After Constantine decided to Christianize the Empire, Easter was changed to represent Jesus. But at its roots, Easter (which is how you pronounce Ishtar) is all about celebrating fertility and sex.

St. Paul tells us, “Test everything; hold fast what is good” (1 Thess. 5:21). When it comes to this Eostre-Ishtar-Easter claim, we can conceive of a situation where cultural practices are “baptized” by retaining certain elements while letting problematic ones go. If that were the case with Easter, it wouldn’t be a big deal, just as it isn’t a big deal when we find it elsewhere. If the original custom was about celebrating fertility and sex, it is certainly not about that anymore. It’s all about the resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Any Catholic will tell you that. So you could simply dismiss claims like these when you encounter them and not worry much about whether they’re true or not.

But some Christian fundamentalists, neopagans, and atheists will use arguments like the one from the viral graphic—albeit in slightly modified ways and for different reasons—as a stick to beat Catholics as we near our most important celebration of the year. I don’t like being beaten with sticks, especially when I know that my assailants are on shaky ground.

The truth is that historians know jack squat about “Eostre.” The only primary source we have in the entire historical record comes from St. Bede, an English Catholic monk. On this topic, he writes,

Eosturmonath has a name which is now translated “Paschal month”, and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance (The Reckoning of Time, 725 AD).

That’s it, folks. Everything we know about this so-called “Eostre” is right there in that short quote. And Bede may have been mistaken. “Eostre” doesn’t show up in the surviving mythologies of any of the surrounding areas as one might expect. Some writers have speculated that this goddess was localized, but that raises the question: why would the Catholic Church bother to create a holiday simply to supplant the celebration of one or two backwoods tribes? Surely, Catholic leadership in those days could have chosen to appropriate the holidays of more notable pagan gods!

The fact that we know virtually nothing about “Eostre”—or even if there was such a goddess at all—makes the jump from her to the Babylonian deity Ishtar even more perplexing. Some neopagans attempt to make the connection through the etymology of the words. “Eostre” likely comes from the Old English word Ēastre, which was a reference to springtime or the dawn. From this perspective, proponents of the Ishtar theory must cobble together bits and pieces of other “goddesses of the dawn.”

It should be noted that the Christian celebration of the resurrection of Jesus is called “Easter” only by English-speaking Christians. The rest of the world calls it Pascha—or some derivative of that—which means “Passover” to commemorate the sacrifice of Our Lord, our “paschal lamb.”

Another claim made in the Ishtar graphic is that bunnies and eggs are fertility symbols, like the ones associated with Ishtar. I suppose that in some cultures they are seen as fertility symbols, but they are not associated with Easter in every culture.

There is no clear historical explanation for how these symbols came to be connected to Easter in the United States. Some scholars think German migrants may have brought the custom with them. History.com explains:

According to some sources, the Easter bunny first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws.” Their children made nests in which this creature could lay its colored eggs. Eventually, the custom spread across the U.S. and the fabled rabbit’s Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts, while decorated baskets replaced nests. Additionally, children often left out carrots for the bunny in case he got hungry from all his hopping.

My own personal belief is that these customs—like milk and cookies for Santa at Christmas—developed as something fun to do with the kids. They likely don’t have any deep connection to the holidays themselves. Even if a connection to ancient pagan practice could be demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt, their original significance has been lost to the passage of time.

And finally, what good anti-Catholic conspiracy theory doesn’t involve the Roman emperor Constantine? Although it has been said that Constantine did much to allow the Christian religion to flourish, it’s a stretch to claim he decided to “Christianize the empire,” altering the celebration of Easter to represent the resurrection of Jesus. Constantine called for the Council at Nicaea to settle the Arian controversy, and while it was convened, the council fathers also settled the debate over when to celebrate Easter. The feast was already being celebrated at that time. The dispute was only about what day it should fall on. That’s the extent of the connection.

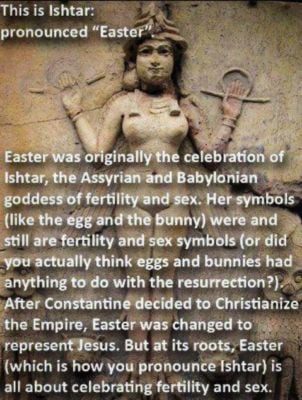

There is a great lesson in apologetics in all of this. Whenever you are confronted with claims that some element of Catholic customs or practice were “borrowed” from ancient pagan religions, you can rest easy knowing that most of these are based on speculation, or on dated or shoddy scholarship. If you run across this popular image on social media this Easter season, please feel free to use the graphic below as a response.