Recently, I and about a dozen others sat in a cavernous stadium-seating movie theater to watch a special screening of Patterns of Evidence: The Moses Controversy (2019)—the latest film by Evangelical documentary-maker Timothy Mahoney.

It follows his earlier film, Patterns of Evidence: Exodus, and deals with the question of whether Moses wrote the first five books of the Bible (called the Pentateuch). According to publicity for the film:

Rocked by questions about his faith, award-winning investigative filmmaker Timothy Mahoney seeks scientific evidence that Moses actually wrote the first books of the Bible—despite the skepticism of mainstream scholars.

Since the Bible claims that Moses was the author of one of the greatest stories in the entire Bible—the Israelites’ exodus out of Egypt and their journey to Mt. Sinai where Moses received the Ten Commandments from God—Mahoney realizes that the question of Moses’ ability to write its first books impacts the credibility of the entire Bible.

So . . . a lot is on the line. According to Mahoney’s publicists, it’s “the credibility of the entire Bible.”

Having seen the film, what can I report?

The Good

Mahoney is very winning and likeable. He comes across as a humble, sincere, and gentle man. What I found especially admirable was that, even when he caught advocates of opposing views in obvious mistakes, he didn’t lord it over them. He treated the subject in a charitable manner, noting the problem and moving on in a gentlemanly way. Kudos to him for that!

The film is well made, using helpful computer-generated charts and nice footage of Egypt and the Holy Land. Mahoney strove to keep things moving by going to interviews with experts, and he let both experts who agreed and who disagreed with him have their say.

Especially compelling was the fact that he put his own faith on the line, suggesting that if he didn’t come up with reasonable answers, it would be hard for him to believe. In this he came across as quite sincere, saying that he had experienced a crisis of faith over these issues some years ago. That’s effective filmmaking.

The Not-As-Good

The film was somewhat slow-paced. If you see it, expect to spend two and a half hours in the theater, and be warned that it includes a twelve-minute intermission in the middle.

The content is kept at a very basic level. Mahoney skates over the surface of the data, never taking the deep dive needed to prove or disprove his case. His basic argument is something like this:

- The Bible teaches that Moses literally wrote the Pentateuch.

- Modern scholars say Moses couldn’t have done this.

- Therefore, the reliability of the whole Bible is on the line.

- However, Moses could have done this.

- Therefore, people can believe in the Bible.

The key points are numbers 1, 2, and 4, and Mahoney spends a huge amount of time on the last of these.

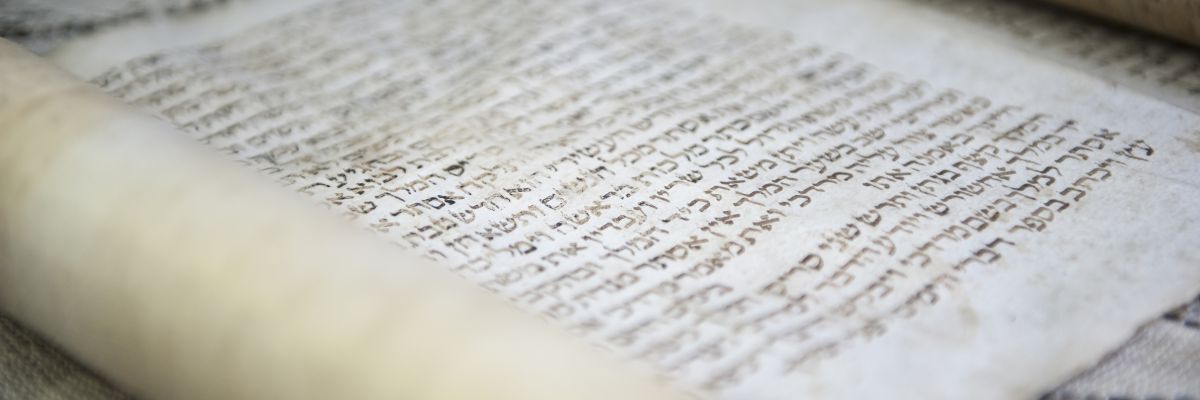

Most of the movie is devoted to arguing that Moses could have written the Pentateuch because there was an alphabet available to him known as the Proto-Sinaitic script, which predates Moses and was used for Semitic languages, the family to which Hebrew belongs.

Mahoney could have stopped there and saved us more than an hour of the film’s running time. Nobody doubts that the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet was in use prior to the time of Moses, so, if Moses wrote the Pentateuch, this is an option for the script he could have used.

In fact, Mahoney doesn’t even need Proto-Sinaitic. As one of the experts he interviews points out, Moses also could have written in the Egyptian hieroglyphic script (or a simplified version of it), and the text could have been transliterated into Hebrew later.

So there were clearly writing systems available in Egypt in Moses’ time, and arguments by skeptical scholars that he couldn’t have written the Pentateuch because the Paleo-Hebrew script hadn’t developed are bunk. We didn’t need to spend an hour or more arguing the point.

And we especially didn’t need to spend an hour listening to interviews with kooky people like David Rohl, investigating his eccentric, alternative chronology of ancient Egypt in an effort to argue that the Proto-Sinaitic script may have been invented by the biblical patriarch Joseph and that it perhaps was given to him by divine inspiration.

None of that provides evidence that Moses wrote the Pentateuch.

(By the way, to give you a sense of how kooky Rohl’s chronology is, he’s doing something for ancient Egypt that is the equivalent of proposing that Jesus lived around A.D. 400! One of Rohl’s most prominent critics—the Evangelical scholar and frequent Old Testament-defender Kenneth Kitchen—termed his chronology “100 percent nonsense.”)

So what evidence does Mahoney offer that Moses did write the Pentateuch? Remarkably little.

At one point he interviews an Evangelical scholar who points out that, in Exodus 17:14, God gives a commandment regarding how to deal with the Amalekite people and tells Moses, “Write this as a memorial in a book” (i.e., a scroll).

But Exodus recording that Moses wrote something in a scroll doesn’t prove that Exodus is that scroll. Exodus describes Moses’ actions in the third person and in the past, and the implication in context is that Moses wrote it in a different book that pre-dated Exodus and was used as one of its sources.

If you were reading a biography of the British author Arthur Conan Doyle and it said that he wrote a book (say, A Study in Scarlet), you wouldn’t infer that A Study in Scarlet is the same book as Conan Doyle’s later biography.

The only other piece of evidence the film offers that Moses wrote the Pentateuch is the fact that, in the Gospels, Jesus sometimes spoke as if Moses was the—or an—author (e.g., Matt. 8:4, 19:8).

However, this was a conventional mode of speech among first-century Jews. Because the Pentateuch chiefly concerns Moses and records legal and historical traditions connected with him, it became common to refer to the Pentateuch as the books of Moses and from there to speak of him as their author. After all, he was held to be the (human) author of many of the laws the books contain.

The question, which the film utterly fails to explore, is whether Jesus was speaking literally or using a conventional but non-literal mode of speech—as if someone today were to say, “The gospel has spread to the four corners of the earth,” knowing full well that the earth doesn’t have four literal corners.

The Moses Controversy spends so much time refuting the idea that Moses couldn’t have written the Pentateuch because the Paleo-Hebrew script hadn’t developed in his time that it never confronts the real evidence suggesting it was written later. This includes facts like:

- The Pentateuch never claims to be written by Moses.

- Its narrative consistently speaks of Moses in the third person (“he” did this, not “I” did this).

- Its narrative consistently speaks of Moses in the past tense.

- It records Moses’ death (Deut. 34).

- It contains passages written from a later perspective, describing how things have remained “to this day” (e.g., Deut. 34:6).

Here we come to the real problem with Mahoney’s reasoning: he was raised in a Fundamentalist home that had an all-or-nothing attitude toward the Bible. If Moses didn’t literally write the Pentateuch, how can you trust anything the Bible says?

The film even notes that the agnostic scholars he interviews were raised in similar homes, and the implication is made that if you allow yourself to doubt Moses’ authorship, you risk losing your faith entirely.

But that doesn’t have to be. There are other positions besides all-or-nothing-ism. For example, one could argue—consistent with the evidence of the Pentateuch itself—that someone else wrote it but drew on legal and historical traditions, and even earlier, written sources, dating from the time of Moses.

This then made it reasonable for later Jews to speak of the Pentateuch as the “books of Moses” and to speak of him as author, even if it was put into its final literary form by someone else.

Although I found The Moses Controversy unsatisfying, it does perform a service—particularly for those who have that all-or-nothing view. (During the filmed panel discussion that followed the movie, some of the audience members I saw it with applauded at key points.)

It’s true that the Proto-Sinaitic script predates Moses, and so he could have used it. Despite the way the Pentateuch presents matters, Moses could have written it (or virtually all of it). It’s not logically impossible.

The film thus provides a way for those with an all-or-nothing view to maintain their faith, and that’s a good thing.

But it’s not the only—or the best—way to view the evidence.