The first time I tried to see the Shroud of Turin was in 1992, but I forgot my x-ray specs, so I caught only a glimpse of a stone box tucked in a badly lit chapel of that city’s Cathedral of St. John the Baptist. I fared better in 1998, when the Shroud was exhibited for the first time in two decades. As I stood in front of the yellowed cloth, stretched and lit in its bulletproof case above the altar, I had a strong and perhaps absurd urge, which at first I resisted. Then I gave in.

I genuflected.

If, as some modern researchers have concluded, the Shroud is a medieval forgery, then I committed gross idolatry that day. On the other hand, and happily for my immortal soul, a 2013 study by Italian scientists called into question the 1988 carbon-dating that placed the Shroud’s origin sometime in the Middle Ages—confirming a long suspicion among Shroud-watchers that residue from a 1532 fire had contaminated those findings—and suggested instead that the cloth dates to a time between 300 B.C and A.D. 400.

Even if the Shroud were not Christ’s burial linen, its origin would still be one of the world’s great mysteries. Its image of a body bearing the marks of torture and crucifixion was not painted on or burned in; it’s not berry juice or coffee or Sharpie. Indeed, we’re not sure how it was created; all we know is that no known ancient technique can account for it. The best modern effort to reproduce it used high-powered UV lasers to create faint radiation burns in strips of cloth.

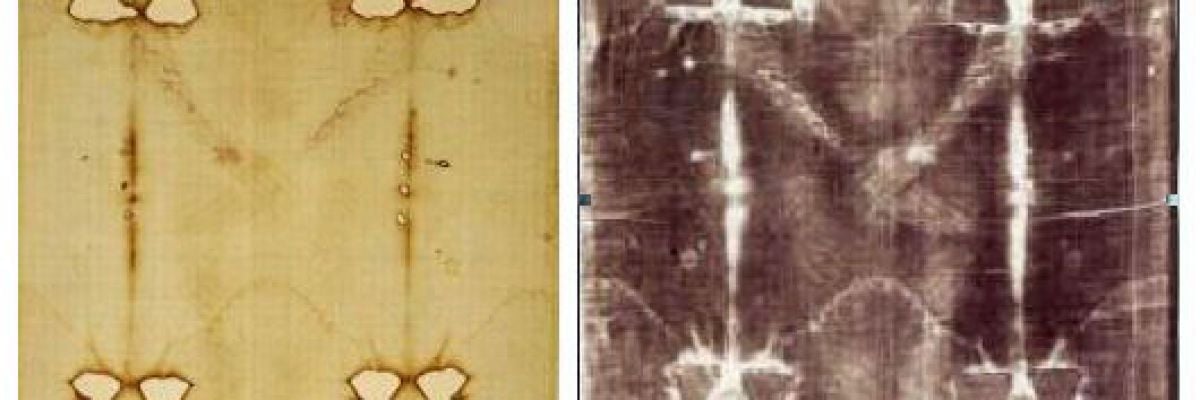

Medieval artists didn’t have laser guns. Neither did they have cameras—and yet the Shroud image is essentially a photographic negative. Long tradition had identified the Shroud as Christ’s burial cloth, but not until the invention of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, which let us look at a negative image of it, were all of its stunning details revealed: front and rear impressions of an adult male laid out in a burial posture, evidence of traumatic wounds at his face, forehead, wrists, feet, and back.

Over the past few decades, forensic analysis has turned up other tantalizing links between the Shroud and the Crucifixion. The weave of the cloth, remnants of bloodstains, traces of stone, soil, and pollen, perhaps even impressions of first-century coins over the figure’s eyes, if accurate, all support or at least do not contradict the Shroud’s identity as a 2,000-year-old burial cloth from the region of Judea.

Now, there is no shortage of Shroud websites (there’s even an iPad app) and no great trick to finding them. The intricacies of Shroud study can exhaust even the most obsessive information hounds. So rather than multiply hyperlinks and factoids, I will leave you to your own curiosity.

But I do want to muse for a moment on how a good Catholic ought to think about the Shroud.

The Church, characteristically, takes no official position on it—just as it takes no position on the tilma of Our Lady of Guadalupe, or on Eucharistic miracles. But the Shroud has enjoyed a place of honor for centuries, and recent popes have approved and even encouraged devotion based on it. Even if it is not Christ’s burial cloth, even if it is not a relic but just an icon, it’s still a compelling mystery and a spiritually profitable reminder of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Our faith is in things unseen, after all; we believe what the Lord revealed because he first opened our eyes and because the Church he founded attests to that revelation—not because Exhibit A contains the DNA proof of it.

But what if it is Christ’s burial cloth? Then it is nothing less than the most singular and splendid thing on earth. Then it is a magnificent sign of God’s mercy, not only because it depicts his greatest act of mercy, but because, even though our faith is in things unseen, he gives us something we can see anyway. This is in keeping with his past M.O. He gave us prophets, miracles, the Incarnation, the Church; many times he has sent his mother and his saints to renew our belief. Salvation history is chock-full of these aids to faith, both for the whole Church and in our own little lives.

But just in case we still didn’t get the message, he gave us “Exhibit A: Resurrection,” too. A huge, glowing neon arrow pointing to the good news. Isn’t that what a God of perfect love and inexhaustible mercy would do?

This is why I choose to believe in the Shroud: not because of what scientists say about it but because of what it says about God.