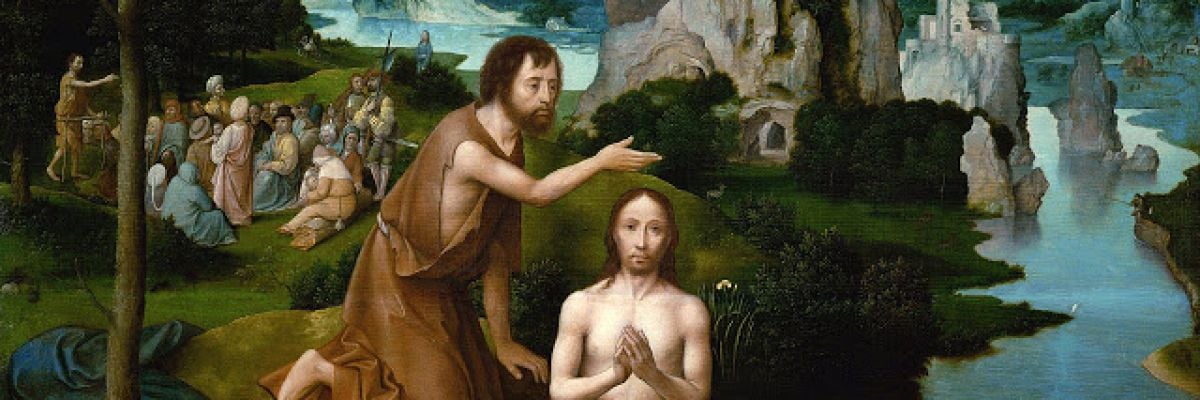

Christians have always known that the four canonical Gospels describe the same major events in Christ’s life but in different ways. For example, consider what God says at Jesus’ baptism. In Mark 1:11 and Luke 3:22, God says, “You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased.” But in Matthew 3:17 God says, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.” So which is it? Did God say, “You are my beloved son” or “This is my beloved son?”

The apocryphal second-century Gospel of the Ebionites proposed a novel answer to this question. In this account, written more than a century after the events it purports to describe, the Father speaks three times—presumably to account for what Matthew, Mark, and Luke record. But this seems implausible given that none of the canonical Gospels—the ones the Church recognizes to be inspired—describe the Father speaking more than once. Besides, would the Father really need to repeat himself to the crowd, or to Jesus, when both could hear what he said the first time?[1]

A better explanation for passages like these is that they differ only in what they say, not in what they assert. This brings us to a good rule of thumb: differing Gospel descriptions do not equal contradictions. A true contradiction in Scripture would occur only when two statements taken together assert that both “X” and “not X” are true at the same time and in the same circumstance. Non-identical descriptions are not necessarily contradictions, because the author may not have asserted the literal truth of every detail in his account. This is understandable, given the nature of ancient historical writing.

How to write history

The second-century Roman author Lucian of Samosata said that the historian “must sacrifice to no God but Truth” and that “Facts are not to be collected at haphazard but with careful, laborious, repeated investigation.”[2] This parallels the prologue of Luke’s Gospel in which the evangelist describes gathering sources in order to create his historical record of what Jesus said and did. Both Luke and Lucian were committed to accurately recording the past, but Lucian also wrote, “The historian’s spirit should not be without a touch of the poetical.”[3]

Consider, for example, how ancient historians recorded speeches that were given decades or centuries earlier. According to Lucian, speeches “should suit the character both of the speaker and of the occasion . . . but in these cases you have the counsel’s right of showing your eloquence.”[4]

In other words, historians can compose speeches with words that were never actually spoken as long as the words they choose are something the person would have said. Thucydides, one of ancient Greece’s most important historians, put it this way: with reference to the speeches in this history, some

were delivered before the war began, others while it was going on; some I heard myself, others I got from various quarters; it was in all cases difficult to carry them word for word in one’s memory, so my habit has been to make the speakers say what was in my opinion demanded of them by the various occasions, of course adhering as closely as possible to the general sense of what they really said.[5]

Historiography scholar Jonas Grethlein corroborates this: “It is widely agreed that most speeches in ancient historiography do not reproduce verba ipissima [what was originally said].”[6] As long as the meaning of the speaker was preserved, an ancient historian was free to use words that differed from what the speaker might actually have said.

We do this even today when we paraphrase speeches given at formal events. After all, when we are asked, “What did the speaker say?” we give a summary with some quotation—not an hour-long recitation.

What is true of ancient historians is also true of the authors of the Gospels. They were concerned with recording history, but their style of historical writing was not the same as the histories we are familiar with today. According to New Testament scholar Craig Keener,

It is anachronistic to assume that ancient and modern histories would share all the same generic features (such as the way speeches should be composed) simply because we employ the same term today to describe both . . . Ancient historians sometimes fleshed out scenes and speeches to produce a coherent narrative in a way that their contemporaries expected but that modern academic historians would not consider acceptable when writing for their own peers.[7]

This is why when we read the Gospels we must distinguish between truths the evangelists were asserting and details they provided to accompany those assertions. The latter could vary in accordance with the standards of ancient historical writing without compromising the truths the author wanted to express to his audience.

Effects on the Gospels

Let’s return to the example of Jesus’ baptism. All three evangelists agree that at this event God publicly revealed himself to be the Father of Jesus. The accounts of Matthew, Mark, and Luke differ only in the words they used to describe that revelation. Matthew chose to emphasize how this message affected the crowd, whereas Mark and Luke emphasized how the message affected Jesus. There is no contradiction, because all three writers are asserting the same truth: that Jesus is God’s Son. They only do so in different ways.

The same can be said of the cock crowing before Peter’s denial. Each evangelist records this detail differently (possibly because they used different sources), but they all assert the same truth: that the cock’s crow coincided with Peter’s denial of Jesus. In fact, sometimes these differences reveal more about the author of a story than the story he was describing.

For example, think about how Mark describes the hemorrhaging woman who Jesus healed. He says she “suffered much under many physicians, and had spent all that she had, and was no better but rather grew worse” (Mark 5:26). Luke, “the beloved physician” (see Colossians 4:14), on the other hand, may not have wanted to unduly criticize his peers, so he simply said the woman “spent all her living upon physicians and could not be healed by any one” (Luke 8:43). Both statements assert the same thing—the best human medicine could not help this woman. They simply describe this fact differently.

In conclusion, Ii is a fallacy to say the Gospels must either be chronologically ordered and detail rich accounts of the life of Christ, or else they must be fictional, theological treatises. Instead, the closest literary genre that describes the Gospels is bioi, or ancient biography.[8]

According to Richard Burridge, ancient biography, “was a flexible genre having strong relationships with history, encomium and rhetoric, moral philosophy and the concern for character.”[9] The purpose of bioi was to recount stories of important people for the purpose of edifying readers, not merely to recount historical facts in the life of a certain person.

Burridge goes on to say, “[T]rying to decode the Gospels through the genre of modern biography, when the author encoded his message in the genre of ancient [biography], will lead to another nonsense—blaming the text for not containing modern predilections which it was never meant to contain.”[10] This includes blaming Mark for not describing Jesus’ infancy, blaming John for not describing events like the Last Supper, or blaming the evangelists as a whole for not conforming to our expectations of a modern biography or newspaper article.

The differences among the Gospel accounts are also typical of ancient Roman historical writing. For example, there are three contradictory ancient accounts of what Emperor Nero did during the Great Fire of Rome in A.D. 64. Some say he metaphorically “fiddled while Rome burned,” but others say he had nothing to do with the fire.[11]

Since scholars rarely doubt the accuracy of non=biblical ancient Roman history in spite of these contradictions, they should give the same benefit of the doubt to the Gospels and not hastily write them off as unhistorical contradictions just because they differ in the details they record.

_____________________________________

Notes

[1] Even Tatian the Syrian, who authored the earliest known attempt to harmonize the four Gospels in the Diatessaron, says that God only spoke once and said, “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (4.28).

[2] “H.W. Fowler and F.G. Fowler, trans., The Works of Lucian of Samosata, Vol. II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1905), 129–31.”

[3] Ibid, 130.

[4] Ibid, 134.

[5] “Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.22.1. Cited in Brant Pitre, The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for “Christ (New York: Doubleday, 2016), 79–81.”

[6] “Jonas Grethlein, Experience and Teleology in Ancient Historiography: “Futures Past” from Herodotus to Augustine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 64.

[7] “Craig Keener, The Historical Jesus of the Gospels (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2009), 110.”

[8] “It has become much clearer that the Gospels are in fact very similar in type to ancient biographies (Greek, bioi; Latin, vitae).” James D.G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003), 185.”

[9] “Richard Burridge, What Are the Gospels?: A Comparison with Graeco-Roman Biography, second edition (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2004), 67.”

[10] Ibid., 249.

[11] “Our main sources for the fire are Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio. All three of these ancient Roman historians agree there was a fire in Rome, but they disagree about the actions of the emperor, who many believed had started the fire in order to free up space for the construction of a future palace. Was Nero not responsible and away in the city of Antium during the fire as Tacitus says (Annals 15.44)? Did Nero send men to burn the city and watch from the tower of Maecenas as Suetonius says (Life of Nero 38)? Or did Nero start the fire himself and watch from the rooftop of the imperial palace as Dio Cassius says (Roman History 62.16–17)? See also Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach (Downer’s Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 570.”