Once a person has entered a state of justification, can this be lost? If so, how would this happen? Protestants have proposed a variety of answers to these questions.

Luther, based on the idea of justification by faith alone, held that it is possible for Christians to lose their salvation, but only through a loss of faith. In other words, only the sin of apostasy—the rejection of the Christian faith—would do this. Any other sins, even great ones like murder or adultery, would not. This view remains standard in Lutheranism today.

However, some Protestants advocate an idea known as eternal security. According to this view, if a person ever enters a state of salvation, he will remain in it for all eternity. It thus is not possible to lose salvation. This view was unheard of in Church history prior to the Reformation. Prior Christians universally acknowledged that salvation was granted through baptism, but it also was clear that some of the baptized later committed sins that the New Testament says will exclude one from the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, the idea of eternal security was a theological novelty when it was proposed in the 1500s.

Eternal security is understood in more than one way among Protestants. Calvinists frequently use the phrase “perseverance of the saints” to describe their understanding of the teaching. According to this view, God will cause authentic Christians to persevere in faith and good works until they die, and this is the reason they are eternally secure: God will not allow them to do those things that would cause them to be lost. If a person does lose faith or fall into grievous sin, it means one of two things: either the person was never an authentic Christian to begin with, or he will return to an authentically Christian life before he dies. In either case, someone who is truly a Christian “can neither totally nor finally fall away from the state of grace; but shall certainly persevere therein to the end, and be eternally saved.”

Another view of eternal security is sometimes expressed with the phrase “once saved, always saved.” This view is found among some non-Calvinist Protestants, and it holds that true Christians can and do fall away from the faith or fall permanently into grievous sin, yet they do not lose their salvation. A single moment of saving faith, at any point in one’s life, is sufficient to permanently cancel all of one’s sins, even those not yet committed. Therefore—at least in terms of salvation—it does not matter what one later does. This view is often associated with advocates of free grace theology.

Not all Protestants have views as extreme as these. Some are much closer to the traditional Christian view. Thus, members of the Methodist, Wesleyan, Holiness, and Pentecostal movements, as well as some others, acknowledge that it is possible for a believer to commit grievous sin and fall from grace. The precise conditions under which this would happen are not definitively worked out, and Protestants do not typically use the language of venial and mortal sin, but it is acknowledged that falling into particularly severe sin would cause a loss of salvation.

The Catholic Church recognizes, based on the clear teaching of the New Testament, that it is possible for Christians to lose their salvation. St. Paul explicitly warns Judaizing Christians, “You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the Law; you have fallen away from grace” (Gal. 5:4). He also tells his audience of Corinthian Christians, “Do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived,” and he goes on to list multiple sins, warning that those who commit them will not “inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor. 6:9–10).

If it is possible to lose salvation, can we get it back? A minority of Protestants have held that it is not. Luther opined that if one commits apostasy, there is no way to regain salvation. But most Protestants who believe it is possible to lose salvation also acknowledge that it is possible to regain it.

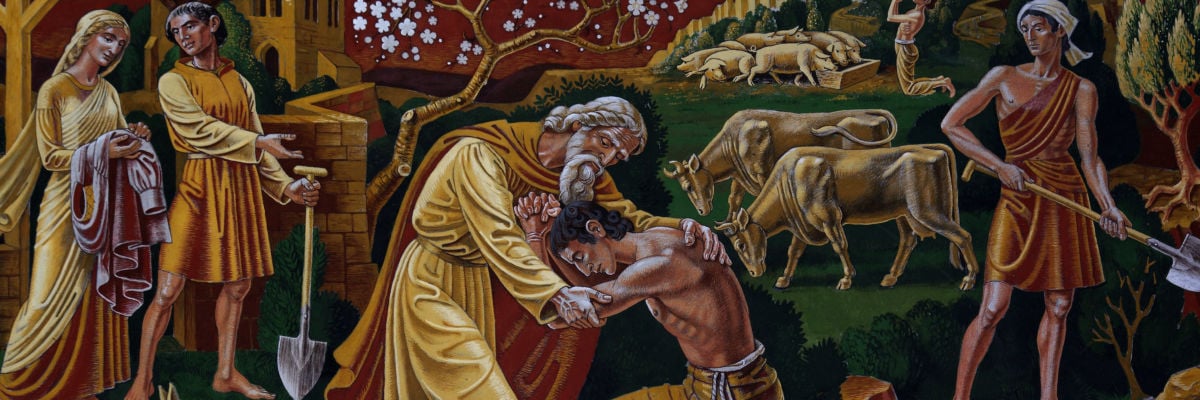

This is the point of the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11–32). In this parable, the father of the family represents God, and one of his sons leaves the family and embarks on a life of sin. Yet he repents and is welcomed back by the father, who declares that the son “was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found” (v. 32). It thus is possible for us to be children of the Father, to leave him for sin and become spiritually dead, and to return and be restored to spiritual life.

The Catholic Church thus acknowledges that it is possible to regain salvation after mortal sin, and that Christ instituted the sacrament of confession for this purpose (John 20:21–23; cf. Matt. 9:8). Therefore, “There is no offense, however serious, that the Church cannot forgive. There is no one, however wicked and guilty, who may not confidently hope for forgiveness, provided his repentance is honest. Christ who died for all men desires that in his Church the gates of forgiveness should always be open to anyone who turns away from sin” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 982).

This is an excerpt from Jimmy’s new booklet, 20 Answers: Faith and Works, on sale now from Catholic Answers Press.