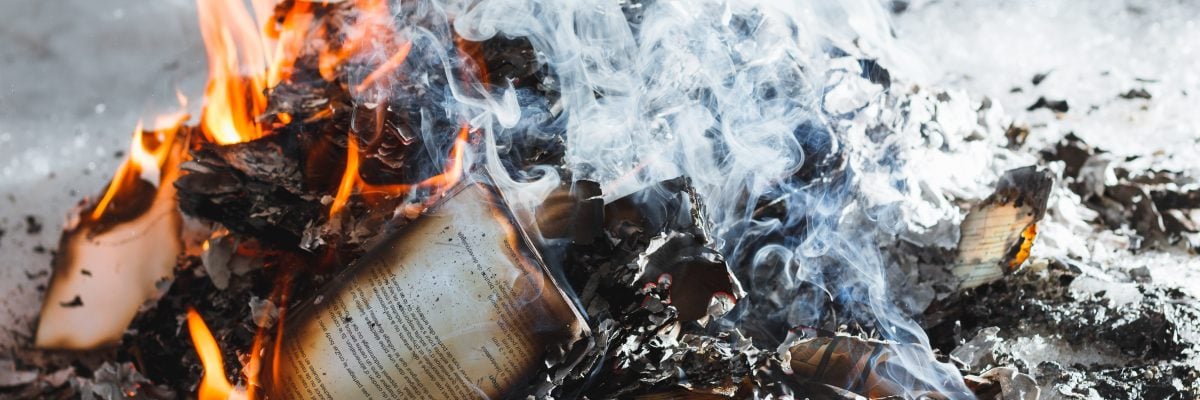

The great Library of Alexandria in Egypt was reportedly one of the largest libraries of the ancient world. Constructed in the third century B.C., it functioned as a center of scholarship. The library was believed to have opened during the reign of either Ptolemy I or Ptolemy II (323-246 B.C.). The function of the library was to collect all of the world’s knowledge, and the staff was responsible for translating the works to be housed there.

Some conspiracy theorists claim that Christians burned it down to hide their pagan roots. Not long ago, I ran across the following online comment:

If the Library at Alexandria had not been torched by a mob of zealots (Christians) we would have a much clearer understanding of the origins of religious practices and beliefs.

(The Library at Alexandria was torched in 400 AD and 750,000 volumes were destroyed – and it is no coincidence that it happened so soon after the Council of Nicea which was partly convened in an attempt to hide the pagan origins of the new faith).

This is yet another trick (from a very large bag of tricks) used to discredit Christianity by suggesting that it had something to hide.

First of all, there is no archeological evidence to suggest that there was ever a building in Alexandria large enough to house 750,000 volumes. In fact, no remains of structures large enough to house 70,000 (the actually number of volumes most commonly believed to have been there) have been discovered. This lack of evidence suggests that the size and scope of the library were exaggerated over time.

Some old encyclopedia entries about the library appear to corroborate the claim that Christians burned it down, but the primary source evidence does not back this assertion at all.

The fact of the matter is that other pagans destroyed this famous library. Between 48 and 47 B.C., Julius Caesar was embroiled in a civil war. Ancient sources say he set fire to his own ships; the fire spread to shore, destroying the library and other structures. In his Life of Caesar, ancient Greek historian Plutarch describes it this way:

[W]hen the enemy endeavored to cut off his communication by sea, he was forced to divert that danger by setting fire to his own ships, which, after burning the docks, thence spread on and destroyed the great library.

This isn’t the only evidence that the contents of the library were destroyed during Caesar’s Alexandrian campaign. Ammianus Marcellinus (AD 378) wrote:

Besides this there are many lofty temples, and especially one to Serapis, which, although no words can adequately describe it, we may yet say, from its splendid halls supported by pillars, and its beautiful statues and other embellishments, is so superbly decorated, that next to the Capitol, of which the ever-venerable Rome boasts, the whole world has nothing worthier of admiration. In it were libraries of inestimable value; and the concurrent testimony of ancient records affirm that 70,000 volumes, which had been collected by the anxious care of the Ptolemies, were burnt in the Alexandrian war when the city was sacked in the time of Caesar the Dictator (Roman History, 22).

Eastern Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart dismantles this myth in an article that appeared in First Things magazine:

The tale of a Christian destruction of the Great Library—so often told, so perniciously persistent—is a tale about something that never happened. By this, I do not mean that there is some divergence of learned opinion on the issue, or that the original sources leave us in some doubt as to the nature of the event. I mean that nothing of the sort ever occurred.

Other scholars have suggested that, if the Christians weren’t responsible for the destruction of the library itself, they may have been responsible for the destruction of a “daughter library,” which the patriarch of Alexandria supposedly destroyed in 391. To this Hart responds:

[I]n fact, there is not a single shred of evidence—ancient, medieval, or modern—that Christians were responsible for either collection’s destruction, and no one before the late eighteenth century ever suggested they were.