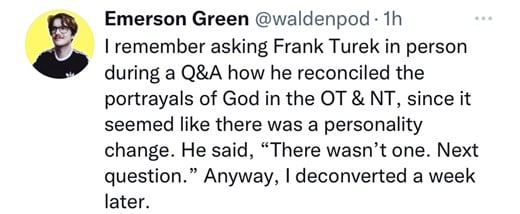

On Twitter, atheist Emerson Green shares an important moment from his own journey:

I’ve never heard Turek’s side of the story, but regardless: this is a good reminder for apologists not to be smug and dismissive. St. Peter tells Christians, “Always be prepared to make a defense to any one who calls you to account for the hope that is in you, yet do it with gentleness and reverence” (1 Pet. 3:15-16, emphasis added).

So what would be a better answer to Emerson’s question?

If you read a theology book written for kids and then one written for adults, they’re going to sound pretty different, even if they have the same author. The same is true in religious texts addressed to a nation. Texts that are targeted at newcomers to this whole “how to be Jewish” thing sound odd when compared to texts preaching to a nation that has been saturated in the Jewish scriptures for centuries. So what we’re seeing isn’t a shift in God’s personality, but the different stages of education.

Pope Benedict XVI makes this point in Verbum Domini, pointing out that “biblical revelation is deeply rooted in history. God’s plan is manifested progressively and it is accomplished slowly, in successive stages and despite human resistance. God chose a people and patiently worked to guide and educate them” (42).

As any parent or teacher can tell you, teaching small children is much different than teaching teenagers or adults:

- Your explanations to little kids are incomplete and sometimes even imprecise: when my toddler talks about the sun “going to bed” in the evening, it’s not yet time to explain heliocentrism to her. Likewise, the Old Testament talks about things like the sun rising, not because God erred, but because he was communicating at the level his chosen people were ready for.

- Rewards and punishments must be immediate: a treat is a bigger reward for a toddler than the promise that you’ll contribute to her Roth IRA. Likewise, the early books of the Old Testament tend to focus more on immediate rewards (prosperity and loss, or life and death) than long-term ones (heaven and hell).

- A good parent must overlook a lot of behavior that would be totally unacceptable in adults: you choose your battles. And so the Bible “describes facts and customs, such as cheating and trickery, and acts of violence and massacre, without explicitly denouncing the immorality of such things.”

But as Benedict points out, throughout the Old Testament, “the preaching of the prophets vigorously challenged every kind of injustice and violence, whether collective or individual, and thus became God’s way of training his people in preparation for the Gospel.” So there’s not a radical shift between “the God of the Old Testament” and “the God of the New Testament.” Throughout the Old Testament itself, we see a shift in how God relates to his people: not because he’s changed, but because they have.

Finally, Benedict says that “it would be a mistake to neglect those passages of Scripture that strike us as problematic.” In other words, don’t respond to good questions like this one by saying, “next question.” Rather,

we should be aware that the correct interpretation of these passages requires a degree of expertise, acquired through a training that interprets the texts in their historical-literary context and within the Christian perspective which has as its ultimate hermeneutical key ‘the Gospel and the new commandment of Jesus Christ brought about in the paschal mystery.’

If you want to see what the Old Testament means, don’t read it through 21st-century eyes, but listen to how Jesus (and his first-century contemporaries) understood it.