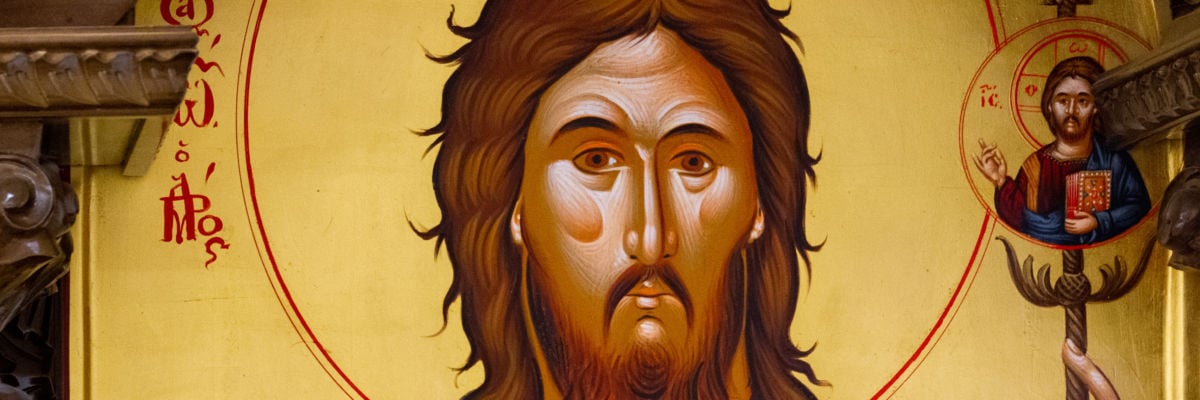

Nazarite (Hebrew: NZYR, NZYR ALHYM, consecrated to God), the name given by the Hebrews to a person set apart and especially consecrated to the Lord. Although Nazarites are not unknown to early Hebrew history, the only specific reference to them in the Law is in Num. (vi, 1-21), a legal section of late origin, and embodying doubtless a codification of a longstanding usage. The regulations here laid down refer only to persons consecrating themselves to God for a specified time in virtue of a temporary vow, but there were also Nazarites for life, and there are even indications pointing to the consecration of children to that state by their parents. According to the law in Num. (vi, 1-21) Nazarites might be of either sex. They were bound to abstain during the period of their consecration from wine and all intoxicating drink, and even from all products of the vineyard in any form. During the same period the hair must be allowed to grow as a mark of holiness. The Nazarite was forbidden to approach any corpse, even that of his nearest relatives, under pain of defilement and consequent forfeiture of his consecration. If through accident he finds himself defiled by the presence of a corpse, he must shave “the head of his consecration” and repeat the operation on the seventh day. On the eighth day he must present himself at the sanctuary with two turtle doves or young pigeons, one of which was offered as a holocaust and the other for sin, and furthermore, in order to renew the lost consecration, it was necessary to present a yearling lamb for a sin offering. At the expiration of the period determined by the vow the Nazarite brought to the sanctuary various offerings, and with symbolical ceremonies including the shaving of the head and the burning of the hair with the fire of the peace offering, he was restored by the priest to his former liberty (Num., vi, 13-21). The meaning symbolized by these different rites and regulations was in part negative, separation from things worldly, and partly positive, viz. a greater fulness of life and holiness indicated by the growth of the hair and the importance attached to ceremonial defilement. The existence of a class of perpetual Nazarites is known to us through occasional mention of them in the Old Testament writings, but these references are so few and vague that it is impossible to determine the origin of the institution or its specific regulations, which in some respects at least must have differed from those specified in Num. (vi, 1-21). Thus of Samson who is called a “Nazarite of God from his mother’s womb” (Judges, xiii, 5), it is merely said that “no razor shall touch his head”. No mention is made of abstention from wine etc., though it has been plausibly assumed by many commentators, since that restriction is enjoined upon the mother during the time of her pregnancy. That his quality of Nazarite was considered to be independent of defilement through contact with the dead is plain from the account of his subsequent career and the famous exploits attributed to him. The prophet Samuel is generally reckoned among the Nazarites for life, but nothing is known of him in that connection beyond what is inferred from the promise of his mother: “I will give him to the Lord all the days of his life, and no razor shall come upon his head” (I Kings, i, 11). It has likewise been inferred from Jer. (xxxv; cf. IV Kings, x, 15 sqq.) that the Rechabites were consecrated to the Lord by the Nazarite vow, but in view of the context, the protest against drinking wine which forms the basis of the assumption is probably but a manifestation on the part of the clan of their general preference for the simplicity of the nomadic as opposed to the settled life. In a passage of Amos (ii, 11, 12) the Nazarites are expressly mentioned together with the Prophets, as young men raised up by the Lord, and the children of Israel are reproached for giving them wine to drink in violation of their vow. The latest Old Testament reference is in I Mach. (iii, 49, 50), where mention is made of a number of “Nazarites that had fulfilled their days.” In the prophecy of Jacob (Gen., xlix, 26), according to the Douay Version, Joseph is called a “Nazarite among his brethren”, but here the original word nazir should be translated “chief” or “leader”—Nazarite being the equivalent of the defective rendering nazaroeus in the Vulgate. The same remark applies to the parallel passage in Deuteronomy (xxxiii, 16), and also to Lam. (iv, 7), where “Nazarites” (Heb. nezerim) stands for “princes” or “nobles”. Nazarites appear in New Testament times, and reference is made to them for that period not only in the Gospel and Acts, but also in the works of Josephus (cf. “Ant. Jud.”, XX, vi, 1, and “Bell. Jud.”II, xv, 1) and in the Talmud (cf. “Mishna”, Nazir, iii, 6). Foremost among them is generally reckoned John the Baptist, of whom the angel announced that he should “drink no wine nor strong drink”. He is not explicitly called a Nazarite, nor is there any mention of the unshaven hair, but the severe austerity of his life agrees with the supposed asceticism of the Nazarites. From Acts (xxi, 23 sqq.) we learn that the early Jewish Christians occasionally took the temporary Nazarite vow, and it is probable that the vow of St. Paul mentioned in Acts, xviii, 18, was of a similar nature, although the shaving of his head in Cenchrae, outside of Palestine, was not in conformity with the rules laid down in the sixth chapter of Numbers, nor with the interpretation of them by the Rabbinical schools of that period. (See Eaton in Hastings, Dict. of the Bible, s.v. Nazarites.) If we are to believe the legend of Hegesippus quoted by Eusebius (“Hist. Eccl.”, II, xxiii), St. James the Less, Bishop of Jerusalem, was a Nazarite, and performed with rigorous exactness all the ascetic practices enjoined by that rule of life.

JAMES F. DRISCOLL