Moses, Hebrew liberator, leader, lawgiver, prophet, and historian, lived in the thirteenth and early part of the twelfth century B.C.

NAME. Hebrew: MSH Mosheh (M. T.), Greek: Mouses, Moses. In Ex., ii, 10, a derivation from the Hebrew Mashah (to draw) is implied. Josephus and the Fathers assign the Coptic mo (water) and uses (saved) as the constituent parts of the name. Nowadays the view of Lepsius, tracing the name back to the Egyptian mesh (child), is widely patronized by Egyptologists, but nothing decisive can be established.

SOURCES. To deny with Winckler and Cheyne, or to doubt, as do Renan and Stade, the historic personality of Moses, is to undermine and render unintelligible the subsequent history of the Israelites. Rabbinical literature teems with legends touching every event of his marvellous career: taken singly, these popular tales are purely imaginative, yet, considered in their cumulative force, they vouch for the reality of a grand and illustrious personage, of strong character, high purpose, and noble achievement, so deep, true, and efficient in his religious convictions as to thrill and subdue the minds of an entire race for centuries after his death. The Bible furnishes the chief authentic account of this luminous life.

BIRTH TO VOCATION (Ex., ii, 1-22). Of Levitic extraction, and born at a time when by kingly edict had been decreed the drowning of every new male offspring among the Israelites, the “goodly child” Moses, after three months’ concealment, was exposed in a basket on the banks of the Nile. An elder brother (Ex., vii, 7) and sister (Ex., ii, 4), Aaron and Mary (AV and RV, Miriam), had already graced the union of Jochabed and Amram. The second of these kept watch by the river, and was instrumental in inducing Pharaoh’s daughter, who rescued the child, to entrust him to a Hebrew nurse. The one she designedly summoned for the charge was Jochabed, who, when her “son had grown up”, delivered him to the princess. In his new surroundings, he was schooled “in all the wisdom of the Egyptians” (Acts, vii, 22).

Moses next appears in the bloom of sturdy manhood, resolute with sympathies for his degraded brethren. Dauntlessly he hews down an Egyptian assailing one of them, and on the morrow tries to appease the wrath of two compatriots who were quarrelling. He is misunderstood, however, and, when upbraided with the murder of the previous day, he fears his life is in jeopardy. Pharaoh has heard the news and seeks to kill him. Moses flees to Madian. An act of rustic gallantry there secures for him a home with Raguel, the priest. Sephora, one of Raguel’s seven daughters, eventually becomes his wife and Gersam his first-born. His second son, Eliezer, is named in commemoration of his successful flight from Pharaoh.

VOCATION AND MISSION (Ex., 11, 23-xii, 33). After forty years of shepherd life, Moses speaks with God. To Horeb (Jebel Sherbal?) in the heart of the mountainous Sinaitic peninsula, he drives the flocks of Raguel for the last time. A bush there flaming unburned attracts him, but a miraculous voice forbids his approach and declares the ground so holy that to approach he must remove his shoes. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob designates him to deliver the Hebrews from the Egyptian yoke, and to conduct them into the “land of milk and honey”, the region long since promised to the seed of Abraham, the Palestine of later years.

Next, God reveals to him His name under a special form Yahweh (see art. Jehovah), as a “memorial unto all generations”. He performs two miracles to convince his timorous listener, appoints Aaron as Moses’s “prophet”, and Moses, so to speak, as Aaron‘s God (Ex., iv, 16). Diffidence at once gives way to faith and magnanimity. Moses bids adieu to Jethro (Raguel), and, with his family, starts for Egypt. He carries in his hand the “rod of God“, a symbol of the fearlessness with which he is to act in performing signs and wonders in the presence of a hardened, threatening monarch. His confidence waxes strong, but he is uncircumcised, and God meets him on the way and fain would kill him. Sephora saves her “bloody spouse”, and appeases God by circumcising a son. Aaron joins the party at Horeb.

The first interview of the brothers with their compatriots is most encouraging, but not so with the despotic sovereign. Asked to allow the Hebrews three days’ respite for sacrifices in the wilderness, the angry monarch not only refuses, but he ridicules their God, and then effectually embitters the Hebrews’ minds against their new chiefs as well as against himself, by denying them the necessary straw for exorbitant daily exactions in brick-making. A rupture is about to ensue with the two strange brothers, when, in a vision, Moses is divinely constituted “Pharaoh’s God“, and is commanded to use his newly imparted powers. He has now attained his eightieth year.

The episode of Aaron‘s rod is a prelude to the plagues. Either personally or through Aaron, sometimes after warning Pharaoh or again quite suddenly, Moses causes a series of Divine manifestations described as ten in number in which he humiliates the sun and river gods, afflicts man and beast, and displays such unwonted control over the earth and heavens that even the magicians are forced to recognize in his prodigies “the finger of God“. Pharaoh softens at times but never sufficiently to meet the demands of Moses without restrictions. He treasures too highly the Hebrew labor for his public works. A crisis arrives with the last plague.

The Hebrews, forewarned by Moses, celebrate the first Pasch or Phase with their loins girt, their shoes on their feet, and staves in their hands, ready for rapid escape. Then God carries out his dreadful threat to pass through the land and kill every first-born of man and beast, thereby executing judgment on all the gods of Egypt. Pharaoh can resist no longer. He joins the stricken populace in egging the Hebrews to depart.

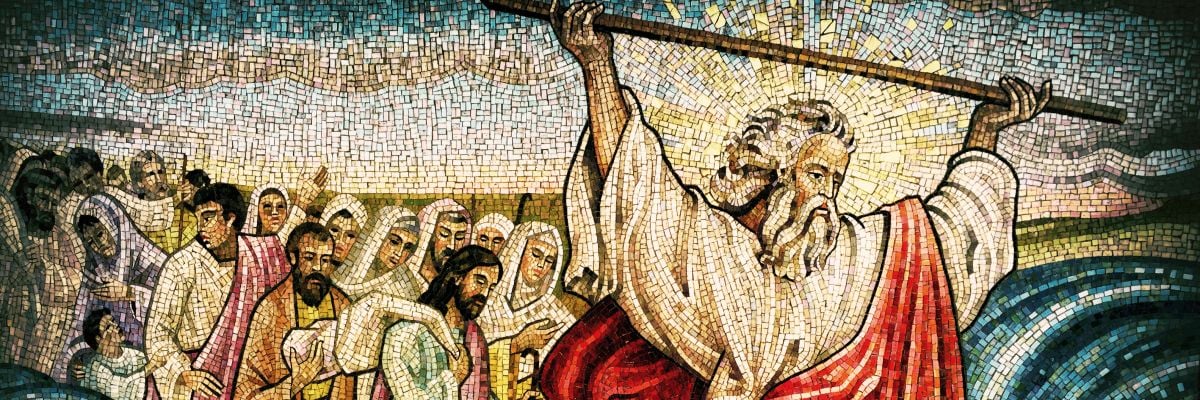

EXODUS AND THE FORTY YEARS (passim after Ex., xii, 34). At the head of 600,000 men, besides women and children, and heavily laden with the spoils of the Egyptians, Moses follows a way through the desert, indicated by an advancing pillar of alternating cloud and fire, and gains the Peninsula of Sinai by crossing the Red Sea. A dry passage, miraculously opened by him for this purpose at a point today unknown, afterwards proves a fatal trap for a body of Egyptian pursuers, organized by Pharaoh and possibly under his leadership. The event furnishes the theme of the thrilling canticle of Moses.

For upwards of two months the long procession, much retarded by the flocks, the herds, and the difficulties inseparable from desert travel, wends its way towards Sinai. To move directly on Chanaan would be too hazardous because of the warlike Philistines, whose territory would have to be crossed; whereas, on the southeast, the less formidable Amalacites are the only inimical tribes and are easily overcome thanks to the intercession of Moses. For the line of march and topographical identifications along the route, see Israelites. subsection The Exodus and the Wanderings., The miraculous water obtained from the rock Horeb, and the supply of the quails and manna, bespeak the marvellous faith of the great leader. The meeting with Jethro ends in an alliance with Madian, and the appointment of a corps of judges subordinate to Moses, to attend to minor decisions.

At Sinai the Ten Commandments are promulgated, Moses is made mediator between God and the people, and, during two periods of forty days each, he remains in concealment on the mount, receiving from God the multifarious enactments, by the observance of which Israel is to be moulded into a theocratic nation (cf. Mosaic Legislation). On his first descent, he exhibits an all-consuming zeal for the purity of Divine worship, by causing to perish those who had indulged in the idolatrous orgies about the Golden Calf; on his second, he inspires the deepest awe because his face is emblazoned with luminous horns.

After instituting the priesthood and erecting the Tabernacle, Moses orders a census which shows an army of 603,550 fighting men. These with the Levites, women, and children, duly celebrate the first anniversary of the Pasch, and, carrying the Ark of the Covenant, shortly enter on the second stage of their migration. They are accompanied by Hobab, Jethro’s son, who acts as guide. Two instances of general discontent follow, of which the first is punished by fire, which ceases as Moses prays, and the second by plague. When the manna is complained of, quails are provided as in the previous year.

Seventy elders a conjectural origin of the Sanhedrin are then appointed to assist Moses. Next Aaron and Mary envy their brother, but God vindicates him and afflicts Mary temporarily with leprosy. From the desert of Pharan Moses sends spies into Chanaan, who, with the exceptions of Josue and Caleb, bring back startling reports which throw the people into consternation and rebellion. The great leader prays and God intervenes, but only to condemn the present generation to die in the wilderness. The subsequent uprising of Core, Dathan, Abiron, and their adherents suggests that, during the thirty-eight years spent in the Badiet et Tih, habitual discontent, so characteristic of nomads, continued. It is during this period that tradition places the composition of a large part of the Pentateuch (q.v.).

Towards its close, Moses is doomed never to enter the Promised Land, presumably because of a momentary lack of trust in God at the Water of Contradiction. When the old generation, including Mary, the prophet’s sister, is no more, Moses inaugurates the onward march around Edom and Moab to the Arnon. After the death of Aaron and the victory over Arad, “fiery serpents” appear in the camp, a chastisement for renewed murmurings. Moses sets up the brazen serpent, “which when they that were bitten looked upon, they were healed”. The victories over Sehon and Og, and the feeling of security animating the army even in the territory of the hostile Balac, lead to presumptuous and scandalous intercourse with the idolatrous Moabites which results, at Moses’s command, in the slaughter of 24,000 offenders. The census, however, shows that the army still numbers 601,730, excluding 23,000 Levites. Of these Moses allows the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half tribe of Manasses to settle in the east-Jordan district, without, however, releasing them from service in the west Jordan conquest.

DEATH AND POSTHUMOUS GLORY. As a worthy legacy to the people for whom he has endured unparalleled hardships, Moses in his last days pronounces the three memorable discourses preserved in Deuteronomy. His chief utterance relates to a future Prophet, like to himself, whom the people are to receive. He then bursts forth into a sublime song of praise to Jahweh and adds prophetic blessings for each of the twelve tribes. From Mount Nebo on “the top of Phasga” Moses views for the last time the Promised Land, and then dies at the age of 120 years. He is buried in “the valley of Moab over against Phogor”, but no man “knows his sepulchre”. His memory has ever been one of “isolated grandeur”. He is the type of Hebrew holiness, so far outshining, other models that twelve centuries after his death, the Christ Whom he foreshadowed seemed eclipsed by him in the minds of the learned. It was, humanly speaking, an indispensable providence that represented him in the Transfiguration, side by side with Elias, and quite inferior to the incomparable Antitype whose coming he had predicted.

THOMAS A K. REILLY