Liturgical Chant.—Taking these words in their ordinary acceptation, it is easy to settle the meaning of “liturgical chant”. Just as we say liturgical altar, liturgical vestment, liturgical chalice, etc., to indicate that these various objects correspond in material, shape, and consecration with the requirements of the liturgical uses to which they are put, so also a chant, if its style, composition, and execution prove it suitable for liturgical use, may properly be called liturgical chant. Everything receives its specification from the purpose it is to serve, and from its own greater or less aptitude to serve that purpose; nevertheless, it is necessary to pursue a finer analysis in order to discover the many possible ways in which the words “liturgical chant’ may be applied. In the strict sense the word “chant” means a melody executed by the human voice only, whether in the form of plain or harmonized singing. In a wider sense the word is taken to mean such singing even when accompanied by instruments, provided the portion of honor is always retained by the vocal part. In the widest though incorrect sense, the word “chant” is also applied to the instrumental music itself, inasmuch as its cadences imitate the inflexions of the human voice, first and most perfect of instruments, the work of God Himself. And thus, after the introduction of the organ into churches, when it began to alternate with the sacred singers, we find medieval writers deliberately using the phrase “cantant organa” or even “cantare in organs”.

Now, seeing that the Church allows in its liturgical service not only the human voice, but an accompaniment thereof by the organ or other instruments, and even organ and instruments without the human voice, it follows that in the sense in which we are going to use it, liturgical chant means liturgical music, or, to employ the more usual phrase, sacred music. Consequently we may consider sacred music as embodying four distinct, but subordinate elements: (I) plain chant, (2) harmonized chant, (3) one or other of these accompanied by organ and instruments, (4) organ and instruments alone. Wherein these elements are subordinate one to another we have to determine from the greater or less aptitude of each for liturgical purposes, and from the greater or less appropriateness of the adjective “liturgical” when applied to them. We shall start with some general observations, and by elimination attain the end we have in view.

Sacred music is music in the service of worship. This is a generic and basic definition of all such music, and it is both obvious and straightforward. When the worship of the true God is in question, man ought to endeavor to offer him of his very best, and in the way it will be the least unworthy of the Divinity. From this root-idea there spring forth two qualities which sacred music should have, and which are laid down in the papal “Motu Proprio,” November 22, 1903, namely—that sacred music ought to be true art, and at the same time holy art. Consequently we cannot uphold as sacred music and suited for liturgical use, any music lacking the note of art, by reason of its poverty of conception, or of its breaking all the laws of musical composition, or any music, no matter how artistic it may be, which is given over to profane uses, such as dances, theatres, and similar objects, aiming albeit ever so honestly at causing amusement (“Motu Proprio, “II, 5). Such compositions, even though the work of the greatest masters and beautiful in themselves, even though they excel in charm the sacred music of tradition, must always remain unworthy of the temple, and as such are to be got rid of as contrary to the basic principle, which every reasonable man must be guided by, that the means must be suited to the end aimed at.

Going a step farther in our argument it must be borne in mind that we are not here dealing with worship of God in general, but with His worship as practiced in the True Church of Jesus Christ, the Catholic Church. So that for us sacred music primarily means music in the service of Catholic worship. This worship has built itself up and has deliberately held itself aloof from every other form of worship; it has its own sacrifice its own altar, its own rites, and is directed in all things by the sovereign authority of the Church. Hence it follows that no music, no matter how much it be employed in other worships that are not Catholic, can, on that account, ever be looked on by us as sacred and liturgical. We meet at times with individuals who remind us of the music of the Hebrews, and quote “Praise him with sound of trumpet: praise him with psaltery and harp. Praise him with timbrel and choir: praise him with strings and organs. Praise him on high sounding cymbals: praise him on cymbals of joy: “and who seek by so doing to justify all sorts of joyousness in church (chants, instrumental music and deafening noises), even going so far as to plead “omnis spiritus laudet Dominum” as though that verse should excuse all and everything their individual “spirit” suggested, no matter how novel and unusual. If such a criterion were to be admitted, there are many other elements of Hebrew worship we should have to accept, but which the Church rejected long ago as unsuited to the sacrifice of the New Testament and to the spirit of the New Law (cf. St. Thomas, II-II, Q. xci, a. 2, ad 4um). The same remarks apply to the music used in Protestant worship. No matter how serious and solemn, even though it belongs to the style of music the Church recognizes as sacred and liturgical, it ought never be used as a pattern or model, at least exclusively for the sacred music of the Catholic Church. The warm and solemn dignity of Catholic worship has nothing in common with the pallid frigidity of Protestant services. Hence our choice ought to be always and solely guided by the specific nature of Catholic worship, and by the rules laid down by the Fathers, the councils, the congregations, and the pope, and which have been epitomized in that admirable code of sacred music, the ` Motu Proprio “of Pius X.

(3) Finally, the phrase “Catholic worship” must here be taken in its formal quality of public worship, the worship of a society or social organism, imposed by Divine Law and subject to one supreme authority which, by Divinely acquired right, regulates it, guards it, and through lawfully appointed ministers exercises it to the honor of God and the welfare of the community. This is what is known as “liturgical worship”, so styled from the liturgy of the Church. The liturgy has been aptly defined as “that worship which the Catholic Church, through its legitimate ministers acting in accordance with well-established rules, publicly exercises in rendering due homage to God“. From this it is clear that the acts and prayers performed by the faithful to satisfy their private devotion do not form part of liturgical worship, even when performed by the faithful in a body, whether in public or in a place of public worship, and whether conducted by a priest or otherwise. Such devotions not being officially legislated for, do not form part of the public worship of the Church as a social organism. Any one can see the difference between a body of the faithful going in procession to visit a famous shrine of the Madonna and the liturgical processions of the Rogation Days and of Corpus Christi. Such popular functions are not only tolerated, but blessed and fostered by the Church authorities, as of immense spiritual benefit to the faithful, even though not sanctioned as liturgical, and are generally known as extra-liturgical functions. The principal are the Devotion of the Rosary, the Stations of the Cross, the Three Hours Agony, the Hour of the Desolata, the Hour of the Blessed Sacrament, the Month of Mary, the novenas in preparation for the more solemn feasts, and the like. What has been said goes to prove that sacred music may fitly be described as music in the service of the liturgy, and that sacred music and liturgical music are one and the same thing. Pius X has admirably stated the relation between the liturgy of the Church and the music it employs: “It serves to increase the decor et splendor of the ecclesiastical ceremonies”, not as something accidental that may or may not be present, such as the decorations of the building, the display of lights, the number of ministers, but “as an integrant part of the solemn liturgy”, so much so that these liturgical functions cannot take place if the chant be lacking. Further, “since the main office of sacred music is to clothe with fitting melody the liturgical text, propounded for the understanding of the people, so its chief aim is to give greater weight to the text, so that thereby the faithful may be more easily moved to devotion, and dispose themselves better to receive the fruits of grace which flow from the celebration of the sacred mysteries” (“Motu Proprio,” I, 1).

From this teaching it follows: (a) That no music can rightly be considered as liturgical, which is not demanded by the liturgical function, or which is not an integrant part thereof, but which is only admitted as a discretionary addition to fill in, if we may use the expression, the silent intervals of the liturgy where no appointed text is prescribed to be sung. Under this head would come the motets which the “Motu Proprio” (III, 8) permits to be sung after the Offertory and the Benedictus. Now, seeing that these chants are executed during the solemn liturgy, it follows that they ought to possess all the qualities of sacred music so as to be in keeping with the rest of the sacred function.

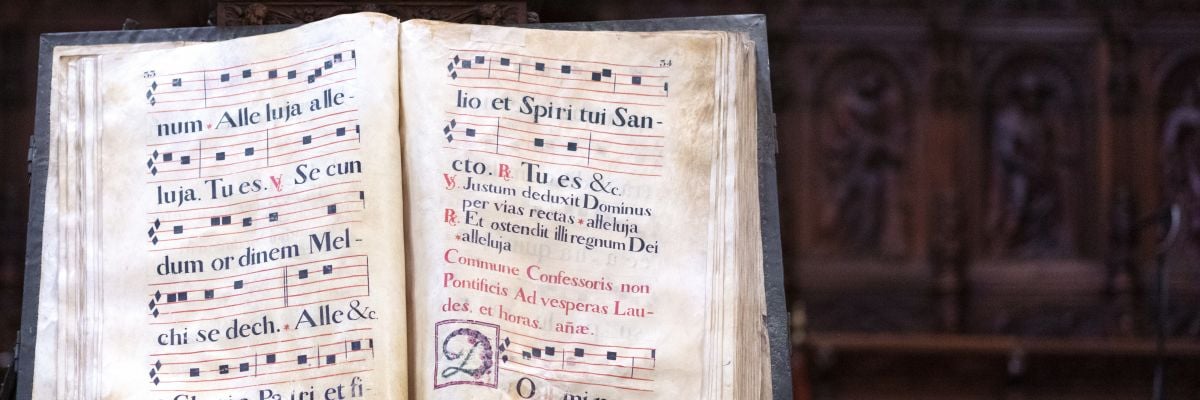

(b) Among the various elements admitted in sacred music, the most strictly liturgical is that which more directly than any other unites itself with the sacred text and seems more indispensable than any other. The playing of the organ by way of prelude or during intervals can only be called liturgical in a very wide sense, since it is by no means necessary, nor does it form an integrant part of the liturgy, nor does it accompany any chanted text. But a chant accompanied by organ and instruments may very properly be known as liturgical. Organ and instruments are permitted, however, only to support the chant, and can never by themselves be considered as an integrant part of the liturgical act. As a matter of fact, their introduction is comparatively recent, and they are still excluded from papal functions. Vocal music generally is the most correct style of liturgical music, since it alone has always been recognized as the proper music of the Church; it alone enters into direct touch with the meaning of the liturgical text, clothes that text with melody, and expounds it to the understanding of the people. Now, since vocal music may be either rendered plain or polyphonic, true liturgical music, music altogether indispensable in the celebration of the solemn liturgy, is the plain chant, and therefore, in the Catholic Church, the Gregorian chant. Lastly, since Gregorian is the solemn chant prescribed for the celebrant and his assistants, so that it is never lawful to substitute for it a melody different in composition from those laid down in the liturgical books of the Church, it follows that Gregorian is the sole chant, the chant par excellence of the Roman Church, as laid down in the “Motu Proprio” (II, 3). It contains in the highest degree the qualities Pope Pius has enumerated as characteristic of sacred music: true art; holiness; universality; hence he has proposed Gregorian chant as the supreme type of sacred music, justifying the following general law: The more a composition resembles Gregorian in tone, inspiration, and the impression it leaves, the nearer it comes to being sacred and liturgical; the more it differs from it, the less worthy is it to be employed in the church. Since Gregorian is the liturgical chant par excellence of the Roman Church, it is equally true that the chant handed down by tradition in other Churches is entitled to be considered as truly liturgical; for instance, the Ambrosias chant in the Ambrosian Church, the Mozarabic in the Mozarabic Church, and the Greek in the Greek Church.

To round off the line of thought we have been pursuing, a few more observations are called for. (a) The music which accompanies non-liturgical functions of Catholic worship is usually and accurately styled extra-liturgical music. As a matter of fact, legislation affecting the liturgy does not ipso facto apply equally to legitimate extra-liturgical functions. And consequently the more or less rigid prohibition of certain things during the solemn offices of the Church does not necessarily ban such things from devotions such as the Way of the Cross, the Month of Mary, etc. To take an example, singing in the vernacular is prohibited as part of liturgical functions. As has been pointed out, music in liturgical functions is an integrant and not a purely ornamental part thereof, whereas in extra-liturgical functions it is altogether secondary and accidental, never exacted by the ceremony, and its main purpose is to entertain the faithful devoutly in Church or to furnish them a pleasing spiritual relaxation after the prolonged tension of a sermon, or whatever prayers they have been reciting together. Hence the style of extra-liturgical music is susceptible of greater freedom, though within such limits as are demanded by respect for God‘s house, and the holiness of the prayer it accompanies. As a sort of general rule it may be laid down that, since extra-liturgical ceremonies ought to partake as much as possible of the externals, as well as of the interior spirit of liturgical ones, avoiding whatsoever is contrary to the holiness, solemnity, and nobility of the act of worship as intended by the Church, so true extra-liturgical music ought absolutely to exclude whatsoever is profane and theatrical, assuming as far as possible the character, without the extreme severity of liturgical music.

(b) Whatever music is not suitable for liturgical or extra-liturgical functions ought to be banished from the churches. But such music is not for that reason to be called profane. There is a distinction to be drawn. There is a style of music that belongs to the theatre and the dance, and that aims at giving pleasure and delight to the senses. This is profane music as distinct from sacred music. But there is another style of music, grave, and serious, though not sacred because not used in worship, yet partaking of some of the qualities of sacred music, and drawing its ideas and inspiration from things that have to do with religion and worship. Such is the music of what are known as sacred oratorios, and other compositions of a religious character, in which the words are taken from the Bible or at times from the liturgy itself. To this class belong the mighty “Masses” of Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, and other classical authors, Verdi’s “Requiem”, Rossini’s “Stabat Mater“, etc., all of them works of the highest musical merit, but which, because of their outward vehicle and extraordinary length, can never be received within the Church. They are suited, like the oratorios, to recreate religiously and artistically audiences at great musical concerts. By way of special distinction, music of this nature is usually designated religious music.