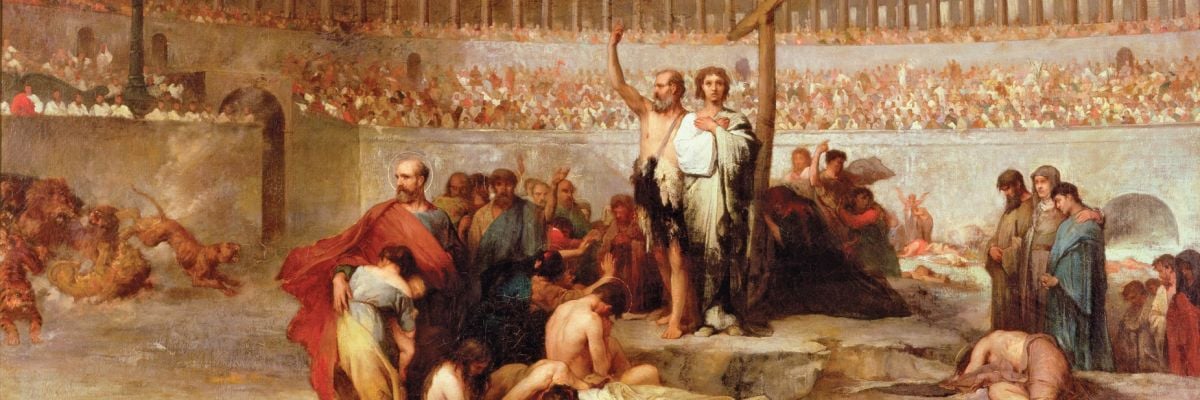

Lapsi (Lat., labi, lapsus), the regular designation in the third century for Christians who relapsed into heathenism, especially for those who during the persecutions displayed weakness in the face of torture, and denied the Faith by sacrificing to the heathen gods or by other acts. Many of the lapsi, indeed the majority of the very numerous cases in the great persecutions after the middle of the third century, certainly did not return to paganism out of conviction: they simply had not the courage to confess the Faith steadfastly when threatened with temporal losses and severe punishments (banishment, forced labor, or death), and their sole desire was to preserve themselves from persecution by an external act of apostasy, and to save their property, freedom, and life. The obligation of confessing the Christian Faith under all circumstances and of avoiding every act of denial was firmly established in the Church from Apostolic times. The First Epistle of St. Peter exhorts the believers to remain steadfast under the visitations of affliction (i, 6, 7; iv, 16, 17). In his letter to Trajan, Pliny writes that those who are truly Christians will not offer any heathen sacrifices or utter any revilings against Christ. Nevertheless we learn both from “The Shepherd” of Hermas, and from the accounts of the persecutions and martyrdoms, that individual Christians after the second century showed weakness, and fell away from the Faith. The aim of the civil proceedings against Christians, as laid down in Trajan‘s rescript to Pliny, was to lead them to apostasy. Those Christians were acquitted who declared that they wished to be so no longer and performed acts of pagan religious worship, but the steadfast were punished. In the “Martyrdom of St. Polycarp” (c. iv; ed. Funk, “Patres Apostolici“, 2nd ed., I, 319), we read of a Phrygian, Quintus, who at first voluntarily avowed the Christian Faith, but showed weakness at the sight of the wild beasts in the amphitheatre, and allowed the proconsul to persuade him to offer sacrifice. The letter of the Christians of Lyons, concerning the persecution of the Church there in 177, tells us likewise of ten brethren who showed weakness and apostatized. Kept, however, in confinement and stimulated by the example and the kind treatment they received from the Christians who had remained steadfast, several of them repented their apostasy, and in a second trial, in which the renegades were to have been acquitted, they faithfully confessed Christ and gained the martyrs’ crown (Eusebius, “Hilt. Eccl.”, V, ii).

In general, it was a well-established principle in the Church of the second and the beginning of the third century that an apostate, even if he did penance, was not again taken into the Christian community, or admitted to the Holy Eucharist. Idolatry was one of the three capital sins which entailed exclusion from the Church. After the middle of the third century, the question of the lapsi gave rise on several occasions to serious disputes in the Christian communities, and led to a further development of the penitential discipline in the Church. The first occasion on which the question of the lapsi became a serious one in the Church, and finally led to a schism, was the great persecution of Decius (250-1). An imperial edict, which frankly aimed at the extermination of Christianity, enjoined that every Christian must perform an act of idolatry. Whoever refused was threatened with the severest punishments. The officials were instructed to seek out the Christians and compel them to sacrifice, and to proceed against the recalcitrant ones with the greatest severity (see Decius). The consequences of this first general edict of persecution were dreadful for the Church. In the long peace which the Christians had enjoyed, many had become infected with a worldly spirit. A great number of the laity, and even some members of the clergy, weakened, and, on the promulgation of the edict, flocked at once to the altars of the heathen idols to offer sacrifice. We are particularly well-informed about the events in Africa and in Rome by the correspondence of St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, and by his treatises, “De catholi ecclesiae unitate” and “De lapsis” (“Caecilii Cypriani opera omnia”, ed. Hartel, I, II, Vienna, 1868-71). There were various classes of lapsi, according to the act by which they fell: (I) sacrificati, those who had actually offered a sacrifice to idols; (2) thurificati, those who had burnt incense on the altar before the statues of the gods; (3) libellatici, those who had drawn up an attestation (libellus), or had, by bribing the authorities, caused such certificates to be drawn up for them, representing them as having offered sacrifice, without, however, having actually done so. So far five of these libelli are known to us (one at Oxford, one at Berlin, two at Vienna, one at Alexandria; see Krebs in “Sitzungsberichte der kais. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien”, 1894, pp. 3-9; Idem in “Patrologia Orientalis”, IV, Paris, 1907, pp. 33 sq.; Franchi de’ Cavalieri in “Nuovo Bullettino di archeologia cristiana”, 1895, pp. 68-73). Some Christians were allowed to present a written declaration to the authorities to the effect that they had offered the prescribed sacrifices to the gods, and asked for a certificate of this act (libellum tradere): this certificate was delivered by the authorities, and the petitioners received back the attestation (libellum accipere). Those who had actually sacrificed (the sacrificati and the thurificati) also received a certificate of having done so. The libellatici, in the narrow sense of the word, were those who obtained certificates without having actually sacrificed. Some of the libellatici, who forwarded to the authorities documents drawn up concerning their real or alleged sacrifices and bearing their signatures, were also called acta facientes.

The names of the Christians, who had shown their apostasy by one of the above-mentioned methods, were entered on the court records. After these weak brethren had received their attestations and knew that their names were thus recorded, they felt themselves safe from further inquisition and persecution. The majority of the lapsi had indeed only obeyed the edict of Decius out of weakness: at heart they wished to remain Christians. Feeling secure against further persecution, they now wished to attend Christian worship again and to be readmitted into the communion of the Church, but this desire was contrary to the then existing penitential discipline. The lapsi of Carthage succeeded in winning over to their side certain Christians who had remained faithful, and had suffered torture and imprisonment. These confessors sent letters of recommendation in the name of the dead martyrs (libelli pacis) to the bishop in favor of the renegades. On the strength of these “letters of peace”, the lapsi desired immediate admittance into communion with the Church, and were actually admitted by some of the clergy inimically disposed to Cyprian. Similar difficulties arose at Rome, and St. Cyprian’s Carthaginian opponents sought for support in the capital in their attack against their bishop. Cyprian, who had remained in constant communication with the Roman clergy during the vacancy of the Roman See after the martyrdom of Pope Fabian, decided that nothing should be done in the matter of reconciliation of the lapsi until the persecution should be over and he could return to Carthage. Only those apostates who showed that they were penitent, and had received a personal note (libellus pacis) from a confessor or a martyr, might obtain absolution and admission to communion with the Church and to the Holy Eucharist, if they were dangerously ill and at the point of death. At Rome, likewise, the principle was established that the apostates should not be given up, but that they should be exhorted to do penance, so that, in case of their being again cited before the pagan authorities, they might atone for their apostasy by steadfastly confessing the Faith. Furthermore, communion was not to be refused to those who were seriously ill, and wished to atone for their apostasy by penance.

The party opposed to Cyprian at Carthage did not accept the bishop’s decision, and stirred up a schism. When, after the election of St. Cornelius to the Chair of Peter, the Roman priest Novatian set himself up at Rome as anti-pope, he claimed to be the upholder of strict discipline, inasmuch as he refused unconditionally to readmit to communion with the Church any who had fallen away. He was the founder of Novatianism (q.v.). Shortly after Cyprian’s return to his episcopal city in the spring of 251, synods were held in Rome and Africa, at which the affair of the lapsi was adjusted by common agreement. It was adopted as a principle that they should be encouraged to repent, and, under certain conditions and after adequate public penance (exomologesis), should be readmitted to communion. In fixing the duration of the penance, the bishops were to take into consideration the circumstances of the apostasy, e.g., whether the penitent had offered sacrifice at once or only after torture, whether he had led his family into apostasy or on the other hand had saved them therefrom, after obtaining for himself a certificate of having sacrificed. Those, who of their own accord had actually sacrificed (the sacrificati and thurificati), might be reconciled with the Church only at the point of death. The libellatici might, after a reasonable penance, be immediately readmitted. In view of the severe persecution then imminent, it was decided at a subsequent Carthaginian synod that all lapsi who had undergone public penance should be readmitted to full communion with the Church. Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria adopted the same attitude towards the lapsi as Pope Cornelius and the Italian bishops, and Cyprian and the African bishops. But in the East Novatian’s rigid views at first found a more sympathetic reception. The united efforts of the supporters of Pope Cornelius succeeded in bringing the great majority of the Eastern bishops to recognize him as the rightful Roman pontiff, with which recognition the acceptance of the principles relative to the case of the lapsi was naturally united. A few groups of Christians in different parts of the empire shared the views of Novatian, and thus enabled the latter to form a small schismatic community (see Novatian and Novatianism).

At the time of the great persecution of Diocletian, matters took the same course as under Decius. During this severe affliction which assailed the Church, many showed weakness and fell away, and, as before, performed acts of heathen worship, or tried by artifice to evade persecution. Some, with the collusion of the officials, sent their slaves to the pagan sacrifices instead of going themselves; others bribed pagans to assume their names and to perform the required sacrifices (Petrus Alexandrinus, “Liber de paenitentia” in Routh, “Reliquiae Sacr.”, IV, 2nd ed., 22 sqq). In the Diocletian persecution appeared a new category of lapsi called the traditores: these were the Christians (mostly clerics) who, in obedience to an edict, gave up the sacred books to the authorities. The term traditores was given both to those who actually gave up the sacred books, and to those who merely delivered secular works in their stead. As on the previous occasion, the lapsi in Rome, under the leadership of a certain Heraclius, tried forcibly to obtain readmission to communion with the Church without performing penance, but Popes Marcellus and Eusebius adhered strictly to the traditional penitential discipline. The confusion and disputes caused by this difference among the Roman Christians caused Maxentius to banish Marcellus and later Eusebius and Heraclius (cf. Inscriptions of Pope Damasus on Popes Marcellus and Eusebius in Ihm, “Damasi epigrammata”, Leipzig, 1895, p. 51, n. 48; p. 25, n. 18). In Africa the unhappy Donatist schism arose from disputes about the lapsi, especially the traditores (see Donatists). Several synods of the fourth century drew up canons on the treatment of the lapsi, e.g., the Synod of Elvira in 306 (can. i—iv, xlvi), of Arles in 314 (can. xiii), of Ancyra in 314 (can. i—ix), and the General Council of Nice (can. xiii). Many of the decisions of these synods concerned only members of the clergy who had committed acts of apostasy in time of persecution.

J. P. KIRSCH